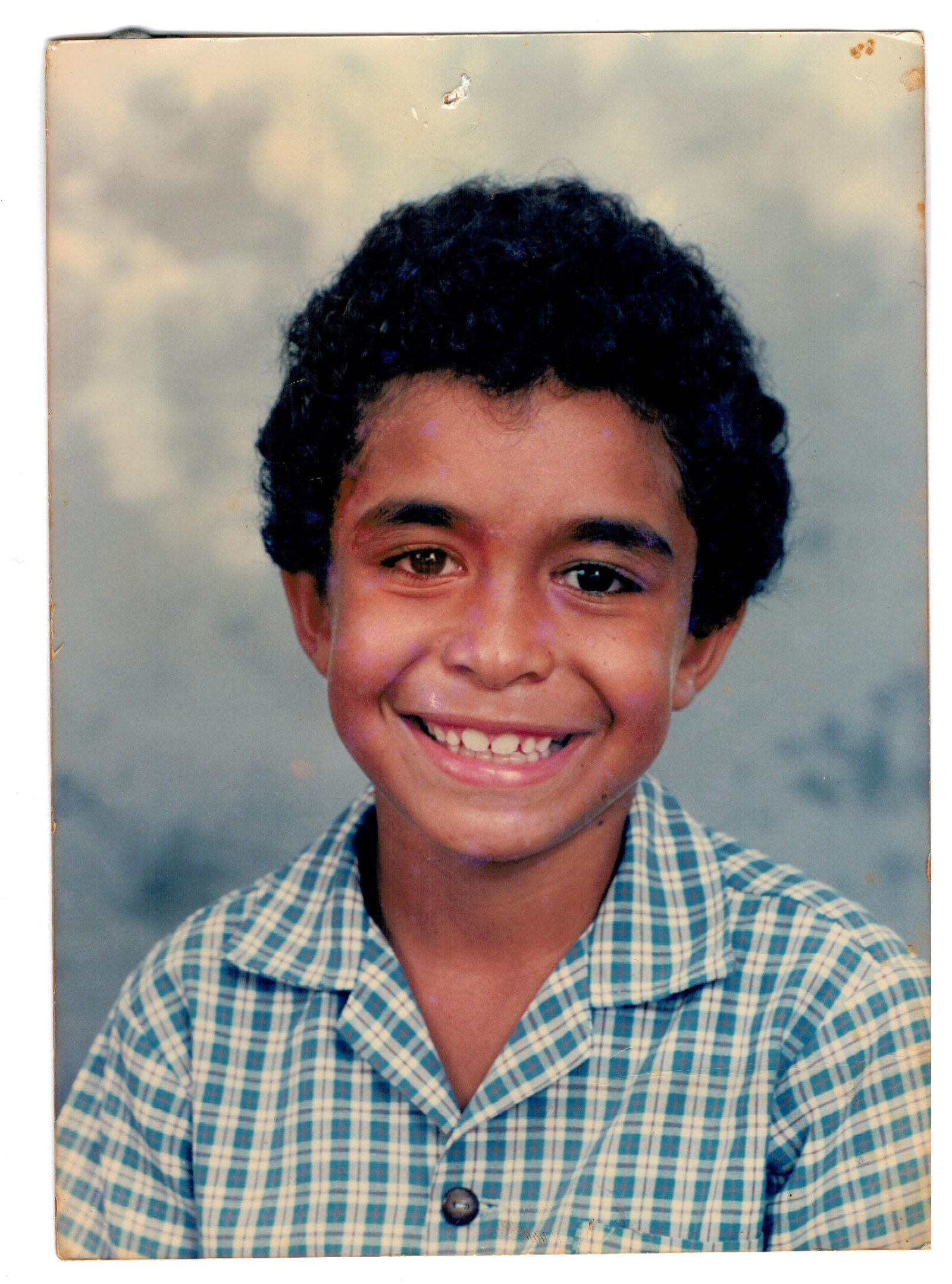

Daniel Love – the Aboriginal man released today from immigration detention after facing deportation to Papua New Guinea, a country he left when he was five years old – is not the first Indigenous person to be threatened with deportation from Australia.

Lawyers and advocates have described other cases to BuzzFeed News in which Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people have ended up in immigration detention, with one saying that “probably a month doesn’t go by” where he doesn’t come across an Indigenous person who is in immigration detention or facing visa cancellation. In some cases, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people have been deported.

The reasons for this are varied and complex, but include a huge increase in visa cancellations on character grounds in the last four years and the fact that some Indigenous people do not know they are not Australian citizens.

Rod Little, co-chair of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, told BuzzFeed News that it wasn’t “right” that Aboriginal people who’d spent most of their lives in Australia should be deported. “If you’re an Aboriginal person, this is your land,” he said.

One Aboriginal man in New South Wales recently spent over seven months in immigration detention facing possible deportation to New Zealand before his visa was reinstated, according to his lawyer.

The lawyer Daniel Ghezelbash, director of Macquarie University’s Social Justice Clinic and special counsel to the National Justice Project, describes his client as being “in a similar position” to Love. His client was born in New Zealand and moved to Australia at a young age.

The man’s permanent resident visa was automatically cancelled after he was sentenced to imprisonment for a number of offences.

The visa cancellation came as a surprise to Ghezelbash’s client, who was not aware that he was not an Australian citizen.

Aboriginal people are “the original inhabitants of this land”, Ghezelbash told BuzzFeed News. “They trace their lineage to long before the arrival of white people and these immigration laws which were imposed on them.

“It’s just preposterous to tell an Aboriginal man or woman who’s traced their lineage back in this country tens of thousands of years that they’re not citizens and they’re being deported.”

While he was still serving his sentence, the man appealed the decision to cancel the visa. When he finished his jail term, he was transferred to immigration detention, where he waited until the government eventually reversed the decision and his visa was reinstated. While Love was released today after nearly two months in detention, Ghezelbash's client sat for over seven months before his release.

“If you are Aboriginal and you have the misfortune of not having citizenship for whatever reason, there is no mechanism in place to screen for this,” Ghezelbash said.

Martin Hodgson, a senior advocate with the Foreign Prisoner Support Service, told BuzzFeed News that "probably a month doesn't go by" where he doesn't come across an Indigenous person who is in immigration detention or has been made aware that they are facing the threat of visa cancellation, although he says that often the threat does not materialise. He says he is also aware of cases where an Aboriginal person has been deported to New Zealand.

“The First Nations are the oldest nations in the existence of men,” said Hodgson. “So to strip an Aboriginal person from their community, from their nation, is to strip a person of 80,000 years of who they are that runs through their veins.”

In the “vast, vast majority” of cases Hodgson has come across, the person threatened with deportation did not know they were not an Australian citizen. “Especially if you have an Aboriginal parent, the obvious assumption is that you’re an Australian citizen, you must be,” he said.

Hodgson described two very similar cases he had been involved in over the past five years. Both were young men in their 20s whose fathers were members of the Stolen Generations and who were born in New Zealand with mothers who were not Australian citizens. Both came to Australia as infants.

“When they were born, their own fathers still had a lot to uncover about their own Aboriginality, where they came from, finding their own family,” Hodgson said. But as their sons grew up, “a lot of that has been resolved”.

“So much so that they become members of the community, they know and are raised in their Aboriginality,” Hodgson said.

He says that while other people who lived most of their lives in Australia have been deported, for Aboriginal people “it’s so often an amalgamation of these injustices of incarceration, intergenerational trauma and the Stolen Generations”.

In each case Hodgson described, the son had their visa cancelled following imprisonment for criminal offences. Both spent time in immigration detention. One was eventually released from immigration detention, and the other was deported to New Zealand but is now back in Australia.

“It is the ultimate insult to the broader family of these young people that they are to be deported given that it could not be more their country,” Hodgson said.

A Victorian lawyer, who did not wish to be identified, also confirmed to BuzzFeed News that they are aware of at least one other case where a person with significant family connections to the Indigenous community in Australia had been detained in immigration detention.

The ABC reported last week that Daniel Love was mounting a High Court challenge to the government’s powers to deport Aboriginal people, arguing that under the Australian Constitution Aboriginal people who are members of the Australian community cannot be deported. However, before the case could go ahead, the Department of Home Affairs decided to revoke his visa cancellation and he was released today.

Love had been in immigration detention in Brisbane since August 10. He was born in Papua New Guinea in 1979 to an Aboriginal Australian father and a Papua New Guinean mother, and he has not left Australia since he was six. He has five children in Australia, all of whom are citizens.

While most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are Australian citizens, a number are not. In the 2016 Australian Census, 1,913 people (0.3% of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander population) reported that they were not Australian citizens, with a further 4% declining to answer the question.

But the number is potentially greater, as the census figures would not account for those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – including Ghezelbash’s client – who are not aware they are not citizens.

A greater number – 0.5% of the Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander population, or 3,317 people – indicated that they were born overseas, with 3% declining to answer.

For those Indigenous people who are not citizens, the law could work unfavourably. As with non-Indigenous people, their visas are automatically cancelled if they are sentenced to 12 months or longer in prison. Indigenous non-citizens have no special legal status under immigration law.

Thalia Anthony, associate professor of law at the University of Technology Sydney, says that being an Aboriginal non-citizen would be a “double burden”. “They suffer the discrimination of being non-citizens, and they suffer the discrimination of being over-criminalised,” she told BuzzFeed News.

While Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults make up around 2% of the national population, they constitute 27% of the national prison population, according to an Australian Law Reform Commission report published in March.

Anthony says Aboriginal people are often policed in a way that leads to criminal histories of very low-level offending that many non-Aboriginal people would not be convicted of, such as intoxication, offensive language and disorderly conduct.

“There is a lot of evidence to say that they are policed more for certain offences, so when they do come to a sentencing court their criminal history looks a lot more extensive than for a non-Aboriginal person who may have committed similar conduct but just not been picked up,” Anthony told BuzzFeed News.

That means that while Aboriginal identity is not relevant to whether someone has Australian citizenship, “it’s relevant in the most adverse way”.

In December 2014 the Migration Act was amended so that visa cancellation for 12-month sentences became automatic, instead of being at the discretion of minister Peter Dutton.

The Department of Home Affairs’ website boasts that the number of visa cancellations on character grounds under the controversial section 501 of the Migration Act, including following criminal convictions, has increased by over 1,400% between the 2013-14 and 2016-17 financial years. 460 people had their visas cancelled in the 2017-18 financial year on character grounds.

“A lot of people, Aboriginal or otherwise, who get their visas cancelled are unaware of the visa consequences of pleading guilty to offences and accepting a particular prison term,” Ghezelbash said.

And in order to address the risk of a person receiving the 12-month sentence, “you’ve first got to know if the person is not an Australian citizen and that may not be a question that’s being asked by all criminal lawyers”, said Rod Hodgson, the lawyer who represented Daniel Love. “I suspect that it wouldn’t be on the forefront of a lot of lawyers’ minds if they’re representing Aboriginal clients, you’d be thinking they’re Australian citizens.”

The minister has the discretion to overturn an automatic cancellation. In 2017, 794 people applied to have their cancellations revoked. In the same year 320 applications were successful, however some of these applications will have dated to before 2017.

Decisions about whether to revoke an automatic cancellation are usually made in accordance with a ministerial direction, which does not explicitly refer to Indigenous identity. The direction includes “primary” and “other” considerations, with primary considerations given greater weight.

Joanne Kinslor, a specialist immigration solicitor and teaching fellow at the University of New South Wales, told BuzzFeed News that a person’s Aboriginality could be considered under one of the “other” considerations — the strength, nature and duration of their ties to Australia. Primary considerations are protecting the Australian community from criminal conduct, the best interests of minor children in Australia and the expectation of the Australian community that non-citizens will obey the law.

“This weighting sets up a decision-making framework in which a non-citizen’s ties to an Indigenous community and Aboriginal identity are unlikely to outweigh considerations in favour of their removal from Australia arising from their criminal conduct,” Kinslor said.

Even when successful, the revocation process can take time. Ghezelbash says it’s common for applicants to wait for “up to a year, if not more”. Martin Hodgson offers a similar estimate.

“They’re banking on the fact that you give up, you leave and you go home,” Ghezelbash said. “If you can start a life anywhere else you’d rather do that than wait indefinitely.”

BuzzFeed News has approached the Department of Home Affairs for comment.

Do you know more? Contact this reporter at hannah.ryan@buzzfeed.com or on Signal at +61 488 601 373