One the most persistent themes of this long and terrible EU referendum campaign has been a deep distrust of experts.

Polling from YouGov showed two-thirds of Leave supporters think "it's wrong to rely too much on so-called experts".

Over two thirds of Leave supporters (+ quarter of Remainers) say it is wrong to rely too much on 'experts'. #EURef

Remain voters, on the other hand, trust various kinds of experts much more.

Fascinating insight from @YouGov: Remain voters trust experts, Leave voters don't trust anyone.

Meanwhile, Michael Gove of the Leave campaign stated recently that "people in this country have had enough of experts".

"People in this country have had enough of experts," claims Michael Gove. #InOrOut

Gove also compared pro-EU experts to Nazis (but, to be fair, said sorry for it later.)

We wanted to find out why people – particularly Leave supporters – feel this way about experts. So naturally, we asked some experts for their expert opinions.

First of all, do people actually hate experts? Jonathan Potter, a professor of discourse analysis at Rutgers University in New Jersey, told BuzzFeed News he doesn't think so.

"In classic studies of persuasion, people tend to trust someone more if they are an 'expert'. It would be odd if it were not the case, really. You don’t go to your idiot uncle when you break your leg, or to the woman that sells cream teas when you want your car fixed."

Potter said that some voters' dismissal of expert opinion is an example of confirmation bias – and the fact that Leave doesn't have very many experts on side.

"You look for information that supports your prior view, and discount that which goes against. So a blanket discounting of experts would be all you are reduced to when they go against you."

OK, so if people don't really hate experts, why have we heard so much about how sneaky experts are?

Dan Gardner, co-author of Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, thinks that people tend to either trust experts too much (because they're lazy) or too little (because they don't like what they're hearing).

"Nobel laureates are human and all humans are capable of talking nonsense," he told BuzzFeed News. Treating experts as infallible "allows us to make quick, low-effort judgments – 'An expert says so? It must be true.' – of exactly the sort our inherently lazy brains prefer."

On the other hand, people may dismiss experts outright – which "allows us to summarily dismiss whole swaths of contrary information," Gardner said.

"Our brains love being able to do that, too, because they prefer keeping things nice and orderly – and when someone comes along and delivers information that contradicts our settled beliefs, things get disorderly."

Well, nobody likes hearing something they don't agree with. But why are certain voters and campaigners getting so mad whenever an expert pipes up?

Colin Provost is a senior lecturer in public policy at University College London. He doesn't think that people hate experts either – but rather, they're just really, really mad at the EU.

"A lot of people look at the EU and see it as a big failure," Provost told BuzzFeed News. "You have the eurozone crisis, the migrant crisis – the anger is often scattered and not particularly strategically aimed. It’s anger in general. It could be at the Tory government, but it’s at the EU.

"So if you really think that’s a problem, if you feel that emotionally, you have a motivated reasoning – you don’t really care what the experts have to say."

People may also mistrust experts if they think experts are slightly dodgy and have something to gain from a Remain victory.

"There's a belief that some EU politicians might be corrupt or incompetent," Provost explained. "The most sinister point of view is that our own politicians are in cahoots with the EU."

(Provost doesn't think this is true...or maybe he has something to gain.)

(He doesn't.)

(Or does he?)

But even people who haven't made up their minds still might not be open to trusting expert advice, because they're just so exhausted by all the information being flung around. (Same.)

"Other people in this country who might not know how they’re voting, who sit on the fence, feel information and leaflet fatigue," Provost said.

"They’ve heard too many arguments, and they don’t know who to believe. There’s too much information coming at them. So it’s not necessarily that they don’t want to hear what experts have to say, it’s that they have expert fatigue."

So people are tired, and also angry. How does this anger affect the way people respond to the Leave and Remain campaigns?

Tereza Capelos is a senior lecturer in political psychology at the University of Birmingham who studies the way that people's emotions affect the way they make political decisions.

She spoke to us about the role in the referendum campaigns of two negative emotions: fear and anger.

The main negative emotion felt by people supporting the Leave campaign, she says, is anger – and that makes people less trusting.

"People who are angry will be less likely to trust anybody, specifically those they don't really have contact with, or don't know. This distrust of experts makes sense for people who feel angry. And these people are very much aligned with Leave."

But on the Remain side, according to Capelos, people are feeling anxious – which can actually lead a person to seek out MORE information (as anybody who's ever convinced themselves they have a rare medical condition by looking at the internet for too long can attest).

"If the predominate emotion you’re feeling is anxiety," Capelos said, "you’re more prone to look for information to appease your anxiety. You are more inclined to be learning things."

If that anxiety tips over into downright fear, however, the effect can change.

"If you’re terrorised – making you panic – then you can have a flight mechanism. You buckle down and become risk-averse and don’t necessarily look for information. You just secure yourself and try not to take any unnecessary risk."

But what's really strange about this referendum, according to Capelos, is that the groups who would normally be risk-averse (pensioners, for example) are supporting Brexit, while those you might expect to be risk-takers (the youth) are more keen on "the risk-averse choice" of remaining.

So why have more traditional, older groups got so ~YOLO~?

Basically, not only has their anger upped their penchant for risk-taking, Capelos said, but much of their support for a Leave vote is inspired by a desire to return to "the way things used to be" before Britain joined the EU.

By looking back in time, people can conjure up "particular narratives and discourses around nationalism", Capelos said.

"For the most part these narratives are gendered, they are sexist, they are masculinised – strong men fighting for their country. These narratives capture their imagination. When you capture someone’s imagination and they are comfortable in that space, it is much easier for a leader or a political party to harness their support by looking back, rather than looking forward to an uncertain future."

And all of that is a lot more powerful to many people than hearing what an economist has to say.

So has the Leave campaign made use of people's anger, or even stoked it?

Professor Clifford Stott of Keele University thinks that people don't always distrust experts, but that the Leave campaign is certainly playing upon antagonism towards academics.

"When you look at the Leave campaign contextually, it’s easy to see why they do this," he said. "All the experts are saying it’s a bad idea. Their only strategy can be to question the validity of experts."

If the Leave campaign had a bigger share of experts supporting its cause, Stott said, "the last thing they’d be doing is criticising the experts."

"Public policy is not always open and sympathetic to expertise, because it’s pursuing a political agenda and has a partisan position. It adopts expertise when it’s favourable and rejects it when it’s not."

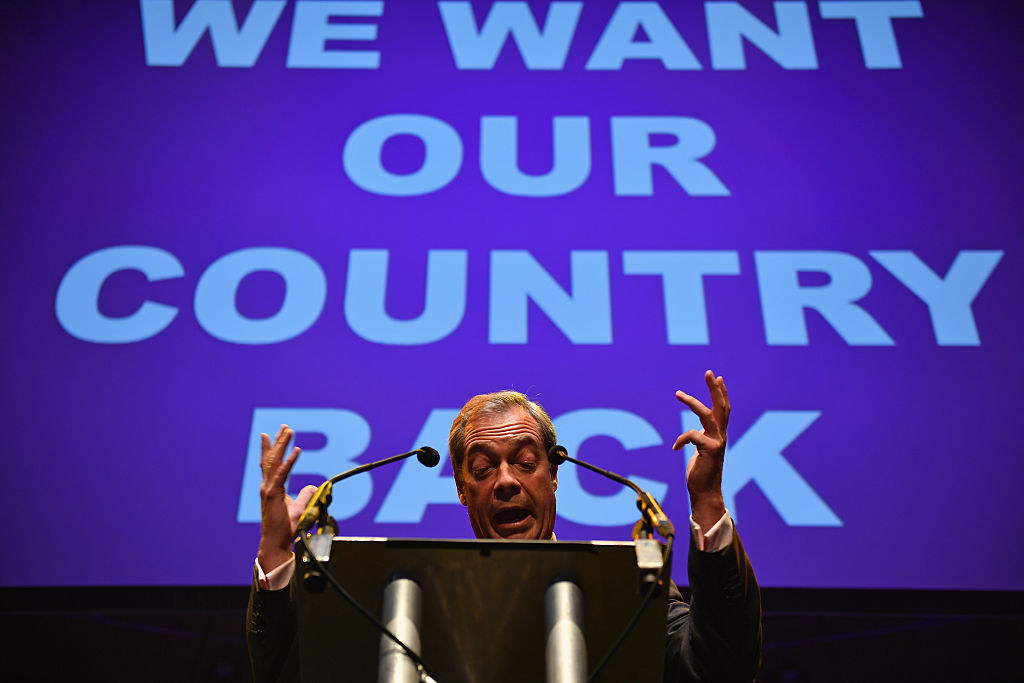

Instead of relying on experts, then, the Leave campaign has had to rely on more populist tactics, said Stott.

"Gove’s attack on expertise is implicitly an attack on intellectualism. Populist politics is anti-intellectual," he said.

So the Leave campaign has managed to lump academics with a more general, vague, threatening-sounding "elite".

"It’s easy to categorise academics as part of the 'elite'," Stott said, "and the popularism of the Leave campaign is contrasting ordinary people against the imaginary elite, which are somehow pernicious and denying the population the opportunities and rights they deserve."

But do experts share any of the blame for the public antagonism against them?

Stephen Reicher, a professor of social psychology at the University of St Andrews, thinks that at least some antagonism towards experts and scientists is thanks to the way they sometimes represent their own work as being infallible.

Reicher said that academics should be better at explaining their work, including disagreements, nuances, and mistakes. "In a sense, because we mistrust the public and think we need to simplify things, they end up mistrusting us," he said.

"Experts, and scientific experts, have a strain of elitism which comes back to bite us."

Reicher also thinks that many people simply harbour a longstanding distrust of the "boffin", imagined as "someone whose brain is so big that they can understand the whole universe, but at the same time can’t tie their own shoelaces."

Understanding an expert this way would lead people to see them "as unlike ordinary people, as not understanding ordinary people, as alien creatures and hence as having little to say that is of relevance to ordinary people."

"This is the root of populism, and the extraordinary spectacle of Eton-educated members of the Tory High Command posing as anti-establishment insurgents."

So is there any hope for the role of experts in the public sphere?

There are some optimists on this front. Professor Michael Dougan of the University of Liverpool recently became a viral sensation for this lecture on European law and what he called the Leave campaign's "dishonesty on an industrial scale".

It's been viewed more than 6 million times across several platforms. (Again: This was a lecture about EU law. That's been viewed millions of times.)

Dougan is not what you'd call a fan of Leave campaign – in fact, he thinks it's "the most dishonest campaign this country has ever seen".

"Anybody who disagrees with them is dismissed as biased, incompetent, or not independent," he told us.

"What they’re trying to do is systematically undermine the credibility of anybody who doesn’t agree with their point of view, and to create confusion in the minds of the public so that they don’t know who to trust."

"I’ve had hundreds of emails telling me I’m in the pay of the European Commission," he said. "I wish I was, but unfortunately my full salary comes from the University of Liverpool!"

(Or does it?)

"I think one of the things I’ve been really struck by about the response to this video and the hundreds of emails I’ve been receiving is that lots of citizens are crying out for objective reasoning and evidence," he said.

"My video going viral means that the politicians and the media have underestimated that people want to understand these things."

Despite also receiving a hearty helping of hate mail in his inbox, Dougan said the thousands of positive responses to his lecture had restored his faith in his fellow citizens "as being basically decent people with a healthy sense of common sense about what’s best for their country".