Muhammad Ali, who died a year ago June 3, is remembered as a boxing legend, an Olympian, a civil rights warrior, a humanitarian, and a trailblazer for Parkinson’s disease awareness.

But one central part of his identity is missing from the official Ali Instagram and Twitter feeds: the proud, unapologetic Muslim.

Islam is conspicuously absent from the Ali brand, which is owned and managed by a New York–based licensing company that also owns the rights to Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and other American superstars. In 2013, Authentic Brands Group paid an undisclosed amount for Ali’s intellectual property, including troves of photos and videos, as well as trademarked slogans such as “Float Like A Butterfly, Sting Like A Bee.”

ABG, as the licensing company is known, runs the Ali social media accounts. With more than 2 million Instagram followers, 876,000 Twitter followers, and 11.8 million Facebook “likes,” the feeds are the main conduit for introducing Ali to a new generation of Americans coming of age after his death. His Facebook biography notes "his early relationship with the Nation of Islam," but the role Islam played in his life stops there. There are black-and-white photos of Ali visiting a hospital, embracing Nelson Mandela, and standing next to Martin Luther King Jr. But in the dozens of photos on posts dating back years, there’s not a clue that “The Greatest” was Muslim, an omission so glaring that it seems deliberate.

Sherman Jackson, a Muslim professor at the University of Southern California who’s written extensively about Islam and black America, said Ali’s religion is an inconvenient fact for companies looking to profit by putting his image on T-shirts, hats, and posters. Jackson, who delivered a eulogy at Ali’s funeral in Kentucky, said the duty now falls to American Muslims to ensure that a central part of his legacy isn’t lost to revisionism and commercialization.

“It’s up to Muslims to really understand his legacy, to really preserve it, and to put it where it ought to be in terms of the pantheon,” Jackson said.

When first reached by BuzzFeed News, Authentic Brands Group spokesperson Haley Steinberg said the company consults closely with the Ali family about how his brand is managed and offered to arrange an interview with a senior marketing officer. A few days later, however, Steinberg said no one was available to comment. When asked why ABG declined to comment, Steinberg stopped replying. Ali’s widow, Lonnie Ali, was asked for comment via email but replied that she was unavailable until mid-August.

Ali’s family has emphasized six core principles as key to his legacy: confidence, conviction, dedication, giving, respect, and spirituality. In public aspects of the Ali legacy, all those values are reflected except spirituality.

Ramadan, the Islamic holy month, came and went without note on the Ali social media feeds. Same for Eid al-Fitr, a big Muslim holiday last month. BuzzFeed News found a single Facebook photo, posted back in 2014, referring to Ali as a Muslim, though he was photographed on many occasions embracing Islam, including on visits to Africa and the Middle East.

Older generations of American Muslims can recall from memory their favorite images. There’s the unforgettable shot of Ali in white pilgrim’s robes performing the hajj. There’s one of him kneeling in a mosque as a ray of light shines upon him through a window. Another shows him sitting cross-legged with his hands cupped in prayer. Or the one of him kissing a Qur’an. Or holding a newspaper with the headline, “Allah is the greatest.” Or hanging out with Malcolm X.

Not one of those photos ever made it to the official Ali feeds that purport to guard his legacy. The feeds celebrate Ali’s activism and humanitarian work without naming the force that fueled it. Ali cited Islam when he filed for conscientious objector status, arguing that the Vietnam War violated teachings of the Qur’an. The Supreme Court eventually sided with Ali, but not before he lost millions of dollars in boxing income and was threatened with jail time.

Islam served as a bridge when Ali traveled to Iraq in 1990 seeking the release of 15 US hostages, and when he asked Iran in 2015 to free then-jailed Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian.

“You’re really whitewashing him, so to speak, by not coming to terms with that. He was Muslim, and he was an American hero. He was black, and he was an American hero,” said Harris Zafar, a national spokesperson for Ahmadiyya Muslims and frequent commentator on US Muslim issues. “That’s how you honor him, not by erasing those traits of his.”

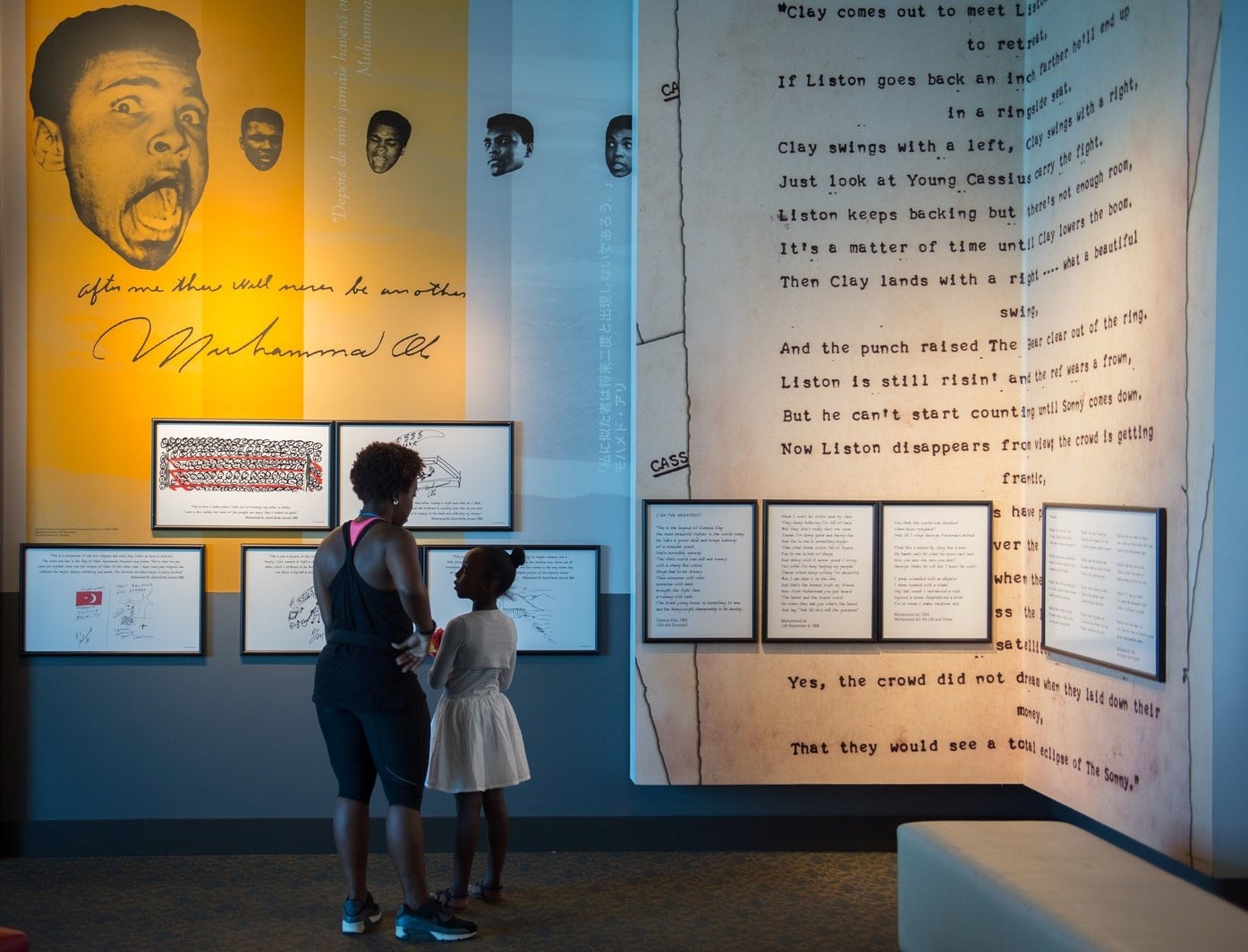

Islam plays a bigger role at another keeper of his legacy, the Muhammad Ali Center in the boxer’s hometown of Louisville, Kentucky. The nonprofit center, a museum and event space for multicultural programs, has a spirituality pavilion that traces Ali’s journey to Islam. Speakers at the center have included several prominent Muslims, Muslims serve on the board, and Ali’s faith was discussed at events this month for the anniversary of his death.

Still, Islam is in the background, absent from the center’s Twitter feed and website.

“We don’t preach one religion over another,” said Becky Morris, a communications and marketing associate at the Ali Center. Quoting Ali, she said, “Rivers and streams all contain the same water.”

Ali made millions through his boxing career, but relied on endorsement and licensing deals once he retired. In 2006, a company controlled by concert promoter Robert Sillerman reportedly paid $50 million for an 80% stake in the rights to Ali’s name, image, likeness, and publicity. That company was then acquired by a private equity firm, which sold the Ali rights to Authentic Brands Group in 2013.

A New York Times report on the sale said ABG’s plans for the Ali brand included deals with airlines, energy drinks, watches, financial services, an Ali hotel, and possibly even a Broadway show. Industry reports list about 40 brands that already have licensed rights to Ali, including Adidas, H&M, Dolce & Gabbana, Under Armour, and the skateboarding clothing line Supreme. The deals are worth millions, though it’s difficult to pinpoint how much money the Ali brand brings in annually. Authentic Brands Group is privately held and hasn’t issued public statements about sales revenues from Ali-related merchandise.

A few Muslim groups have launched a quieter, parallel push to honor Ali’s legacy, recording online sermons and making inspirational memes out of Ali’s many defiant speeches.

Weeks after Ali’s death last year, then-president Barack Obama invited the Ali family to his last White House observance of Eid, the end of the holy month of Ramadan. Zaki Barzinji, who served as the Obama administration’s US Muslim liaison and who attended Ali’s funeral on behalf of the White House, said the theme of the Eid event was Islam’s deep roots in the United States. In his address, Obama said Ali was “as proud of his blackness as he was of his faith.”

“The crux of his remarks were about Muhammad Ali, about how he was a proud African-American, a proud Muslim, an example of how the Muslim community has been so integrated,” Barzinji said.

Jihad Turk, president of Bayan Claremont, an Islamic seminary in Southern California, has raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to launch a new Ali-inspired program that blends Islamic studies and leadership skills.

So far, 14 candidates are in the pipeline for the Muhammad Ali Scholarship for Spiritual Leadership. In a statement released via Bayan, Lonnie Ali said the scholarships “represent an extension of Muhammad Ali’s legacy” by training students to create a better public understanding of Islam.

Turk, who was a signatory to Ali’s will, said the idea was to recognize how Islam is intertwined with the symbolism of Ali.

“It’s not an insignificant or marginal aspect of the story of who Muhammad Ali was,” Turk said. “It was at the core of who he was, as a man and as a legend.”

Muslim fans of Ali said playing down his religious identity is not only unfair, but historically inaccurate. Ali said repeatedly, and with characteristic bluntness: “Being a true Muslim is the most important thing in the world to me. It means more to me than being black or being American.”

Islam wasn’t just important to Ali during life, but also in death. Preparations were years in the making, with careful attention paid to the rituals of the Islamic janazah, or funeral. Arash Markazi, an Iranian-American journalist at ESPN, attended the service, writing that it was “the most significant moment for Muslims in the United States and it was to honor the most significant Muslim in the United States.”

“To ignore Muhammad Ali as a Muslim is to ignore Muhammad Ali as a man,” Markazi wrote at the time. “The two are intertwined.”

Ali’s death drew a rare national outpouring for an American Muslim, with many speakers invoking his lessons of justice and unity as the nation fragmented under the ugly presidential race at the time. Those conciliatory words were obliterated just days later, however, with the massacre at Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

Muslims were back on the defensive, once again smeared as a group by a lone attacker’s actions, just as they were mourning the one man who made it OK, maybe even cool, to be Muslim in America.

“A lot of young people in this age of Islamophobia are really almost starved for heroes who can inspire them to straighten their backs and hold up their heads,” Jackson, the professor, said. “And nobody really personified that as keenly, as forcefully, as unapologetically, as Muhammad Ali.” ●