Those of us in the developed world take our access to banks, credit cards, and Venmo so much for granted that many of us don't even bother to check our account statements once a month. But people in the developing world aren't so lucky.

Women are particularly disadvantaged. Only 50% of women in the developing world — countries like Afghanistan, India, and Nigeria — have a bank account with a financial institution or a mobile money service, compared to 59% of men. Despite an uptick in access, with 500 million new people getting bank accounts from 2011 to 2014, the gender gap (like many other gender divides) in financial access has remained constant. Women and other marginalized groups like the poor and refugees still risk being left "unbanked," without access to lines of credit, savings accounts, and secure ways to transfer money.

In a new study to be published Thursday by the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, researchers found that smartphones are one of the key tools for giving women access to banking in Asia, Africa, and Latin America — but much of the world is still a long way from widespread financial inclusion. The researchers behind the study are calling for renewed efforts to achieve gender parity in banking, and they think mobile technology and nontraditional financial services are the best way to make it happen.

“There are still roughly 2 billion people in the world that are excluded from financial participation," John Villasenor, one of the study's authors, told BuzzFeed News. "And almost everybody recognizes that financial inclusion is a critical part of improving the economic prosperity and growth of a country."

At the most basic level, having access to a bank helps reduce the risk of being robbed, Villasenor explained. Banks offer a way to store cash more securely, and digital banking can save people in underserved communities from long treks and bus rides where they can be targeted by thieves. Without access to banks, people can exchange and save their cash, but less reliably. Other important services like interest-bearing savings accounts, international money transfers, and credit lines are generally only offered by formal institutions.

The study, now in its second year, measured how nations provide financial tools to their underserved populations. The Brookings researchers ranked 26 countries across four categories, including the commitment of governments to increase access to financial services, and a country’s adoption of banking tools.

"There is a clear business case for serving women, who tend to save more relative to their total income than men, repay loans at a higher rate, buy more products per capita, and be more loyal to their bank."

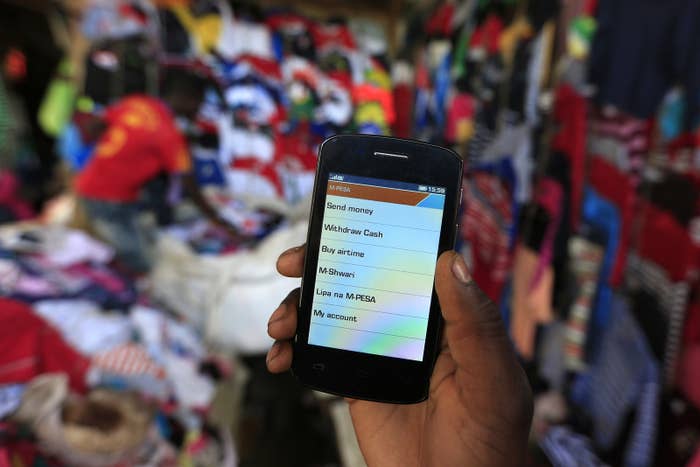

As it did last year, Kenya claimed the top spot, touting one of the most mature markets for mobile money services in the world. Kenya's largest mobile-network operator, Safaricom, allows customers to transfer money through their phones on its mobile money system called M-PESA. M-PESA's massive adoption in the country has helped boost bank account ownership; 75% of Kenyan adults and 71% of Kenyan women have accounts with a financial institution or mobile money provider, which is well above the global average, according to the study.

(According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, about 92% of American households have access to a bank account, but of these households, about 20% are underserved, meaning that they have accounts but also use services outside of the traditional banking system.)

Mobile money has taken off in other African nations too, with Rwanda, Uganda, and Tanzania among the highest-ranking nations in mobile money adoption. It will likely get better: By 2020, the number of smartphones connections is expected to increase from about 4 billion to 6 billion. More mobile phones means more people will have access to digital financial services, like mobile money.

“One of the great trends we are going to see in the next couple of years is this conceptual migration of hundreds of millions of people into the digital world.” Villasenor said, which will help provide access to financial services more efficiently and for less money.

While the cost of smartphones remains a barrier for many women, the study cites a number of initiatives to make phones more affordable. One private industry-backed program in Vietnam offers low-interest loans to workers to purchase appliances and smartphones. Bangladesh has payment plans for phones, and mobile operators in Indonesia, Rwanda, and Turkey have also pledged to increase the proportion of women on their networks by 2020.

"Increasing access to financial services among women enables them to invest in themselves, in their families, and in their communities," the report says. Gender parity in banking has another perk, too: "There is a clear business case for serving women, who tend to save more relative to their total income than men, repay loans at a higher rate, buy more products per capita, and be more loyal to their bank."

To pinpoint which programs and national strategies will best close the gender gap in banking, the researchers said they hoped to gather more gender-specific data in the future. But perhaps even more urgent is the need for information on marginalized migrant workers and refugees, which the researchers said is especially limited. “There’s a huge number of issues that forcibly displaced persons face, and one of them is access to financial transactions," Villasenor said. Without access to banking tools, and facing both language and legal barriers, refugees must often rely on informal channels for transferring money that are costly, unreliable, and dangerous.

According to the United Nations, about 12.4 million people were forced to leave their home countries because of conflict or persecution last year. More than half of these refugees came from just three countries: Syria, Afghanistan, and Somolia. So, armed with more data next year, the Brookings researchers will try to figure out which banking policies will help displaced individuals the most.