A Queensland woman who applied for special consent to terminate her high-risk twin pregnancy has been denied an abortion because a tribunal ruled she did "not have the capacity to make complex decisions about all of her personal matters due to her diagnosed mental illness".

The pregnant 33-year-old was jailed at the Brisbane Women's Correctional Centre in June for breaching bail conditions involving drug use. She has since been living at a mental health facility where she is receiving treatment for schizophrenia.

The woman, who is referred to as QDB, is a classified patient under the Mental Health Act and has no legal capacity, as she has been appointed a public guardian to make legal and health care decisions on her behalf.

She applied to have a termination at 20 weeks of gestation. She told the tribunal she did not want any more children and her parents said they did not think their daughter was capable of looking after children.

The tribunal's job was to establish whether the woman's ability to understand the nature and effect of the decision to terminate her pregnancy was at all compromised, and to decide whether the abortion was necessary to prevent "serious danger to her life or physical or mental health".

Abortion is still in Queensland's Criminal Code and is only lawful if a doctor believes "a woman's physical and/or mental health is in serious danger".

Both doctors consulted by the tribunal agreed that the woman's pregnancy was "a higher risk than a normal pregnancy" because the woman had a "history of drug use, is Hepatitis C positive, has a low-lying placenta and is a moderate to heavy smoker".

"The evidence is that in a worst case scenario, if there was a change to the foetuses left undetected, for example, intrauterine foetal death, QDB was at risk of developing a complication that, if left untreated, could result in her death," the evidence given by doctors and repeated in the tribunal's judgment read.

But the tribunal declared: "We are satisfied that [the woman] does not have the capacity to make the decision to terminate her pregnancy. There is not evidence before us of serious danger to [the woman's] life or physical or mental health if the pregnancy was to continue and therefore consent to termination of pregnancy cannot be given."

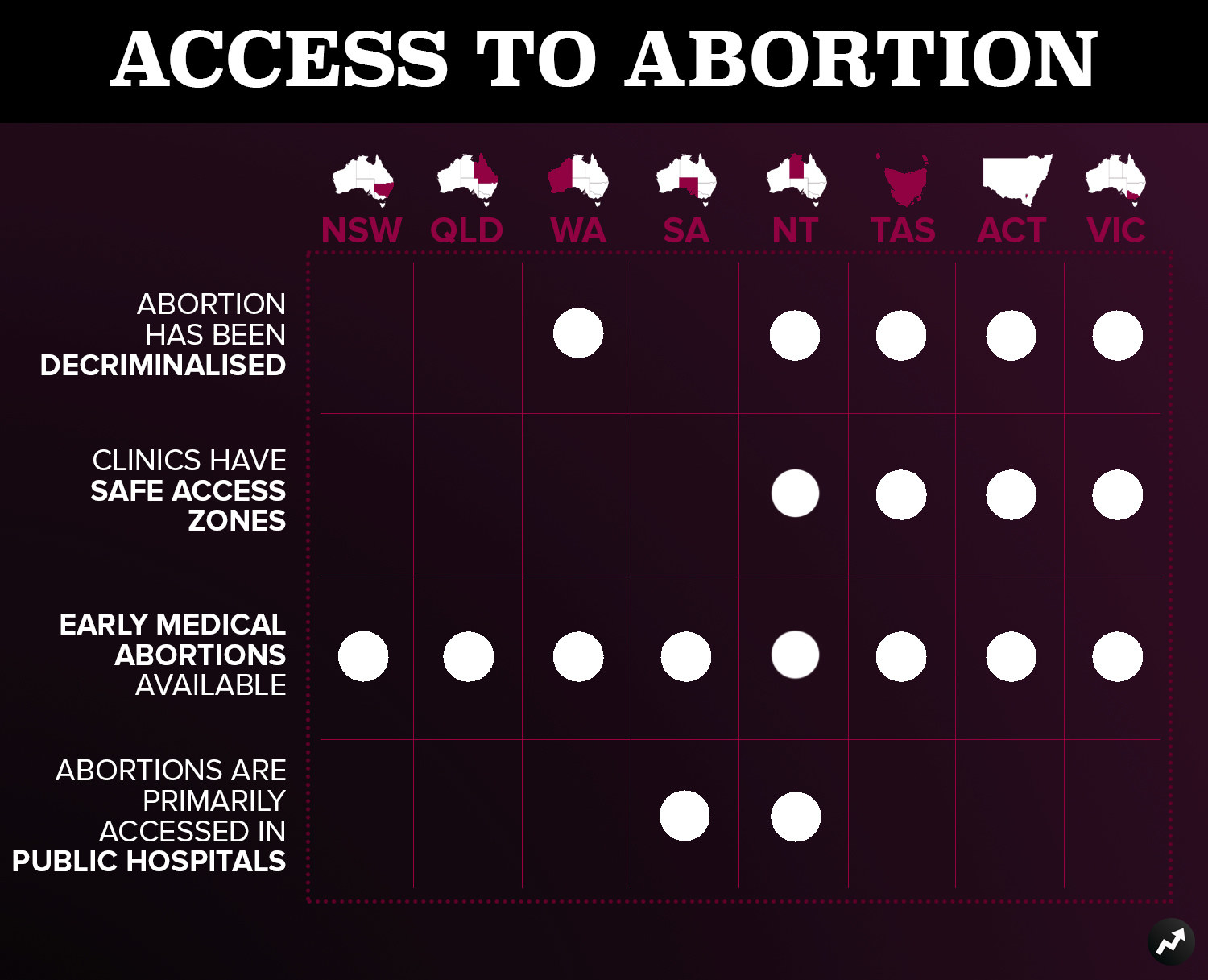

The legality of reproductive healthcare varies drastically from state-to-state across Australia.

Abortion up to and beyond 20 weeks is legal in Victoria, South Australia and the Northern Territory, and Reproductive Choice Australia president Jenny Ejlak told BuzzFeed News the outcome might have been different if the woman had lived outside of Queensland.

"My understanding is that it went to a tribunal because there are a whole heap of legal requirements in Queensland, but if it had been in Victoria where abortion is normally treated as a regular healthcare decision between a woman and a doctor up to 24 weeks, the outcome might have been different," Ejlak said.

"It is a good example of how ridiculous and how complex the law makes healthcare in an already really tragic case. There was no consideration in this ruling given to the welfare of the twins."

Ejlak questioned why the testimony of a psychiatrist — who said the woman was not at risk of post-natal depression despite her history of self-harm — was given "more weight" than the testimony of women's health professionals.

"She has had obstetricians and gynaecologists testify to a tribunal that this pregnancy could result in her death, but the tribunal is still not satisfied that the pregnancy is a risk to her health," she said.

Ejlak said the tribunal was beholden to criminal law which was "written in the mid-1800s", and subsequent precedents set more than 80 years ago.

"The precedents were decided by male judges who based their rulings on previous rulings which were made with the medical knowledge and social mores of the 1930s," she added.

"The law and judicial precedent is out of step with the reality of women having control over their own bodies."