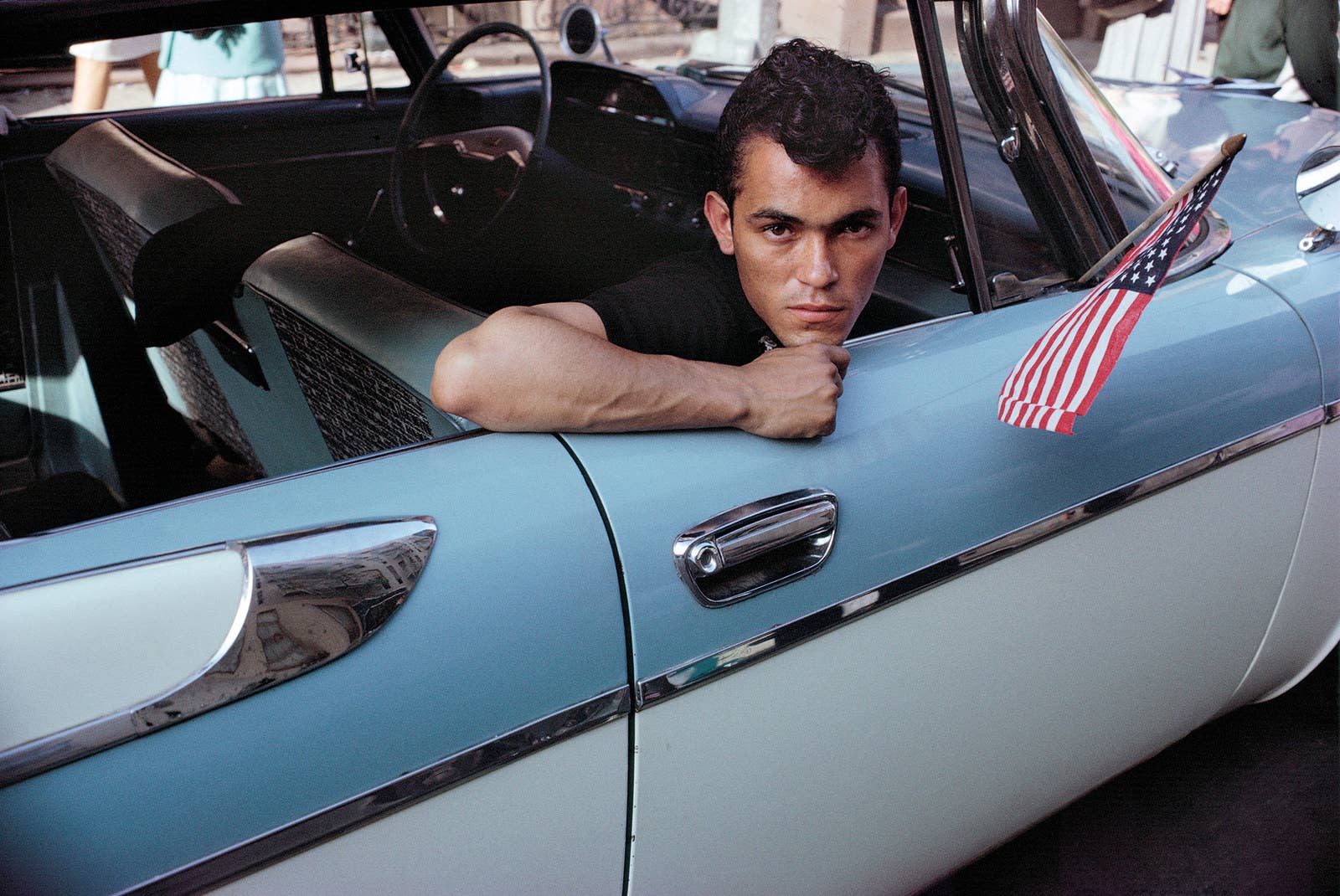

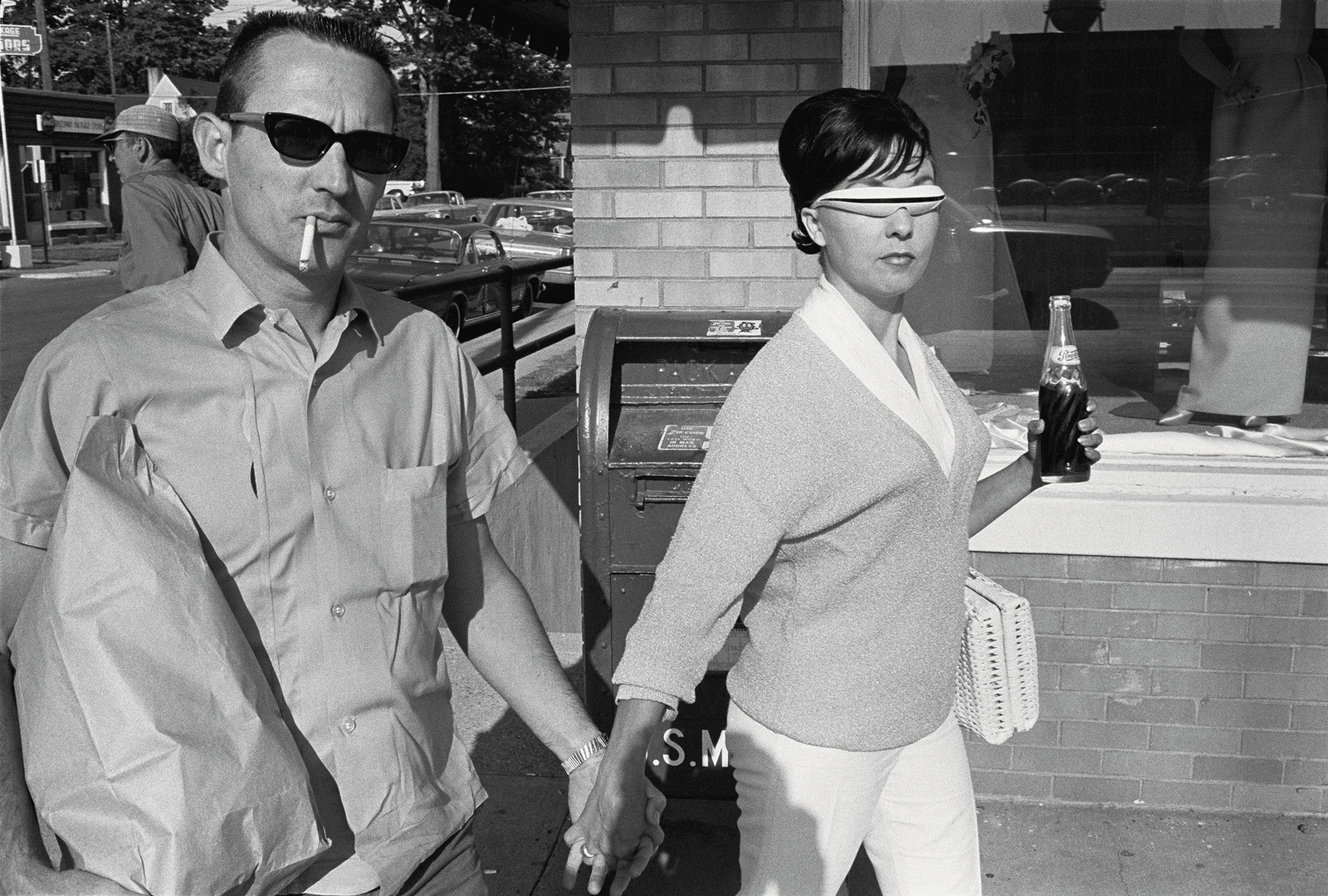

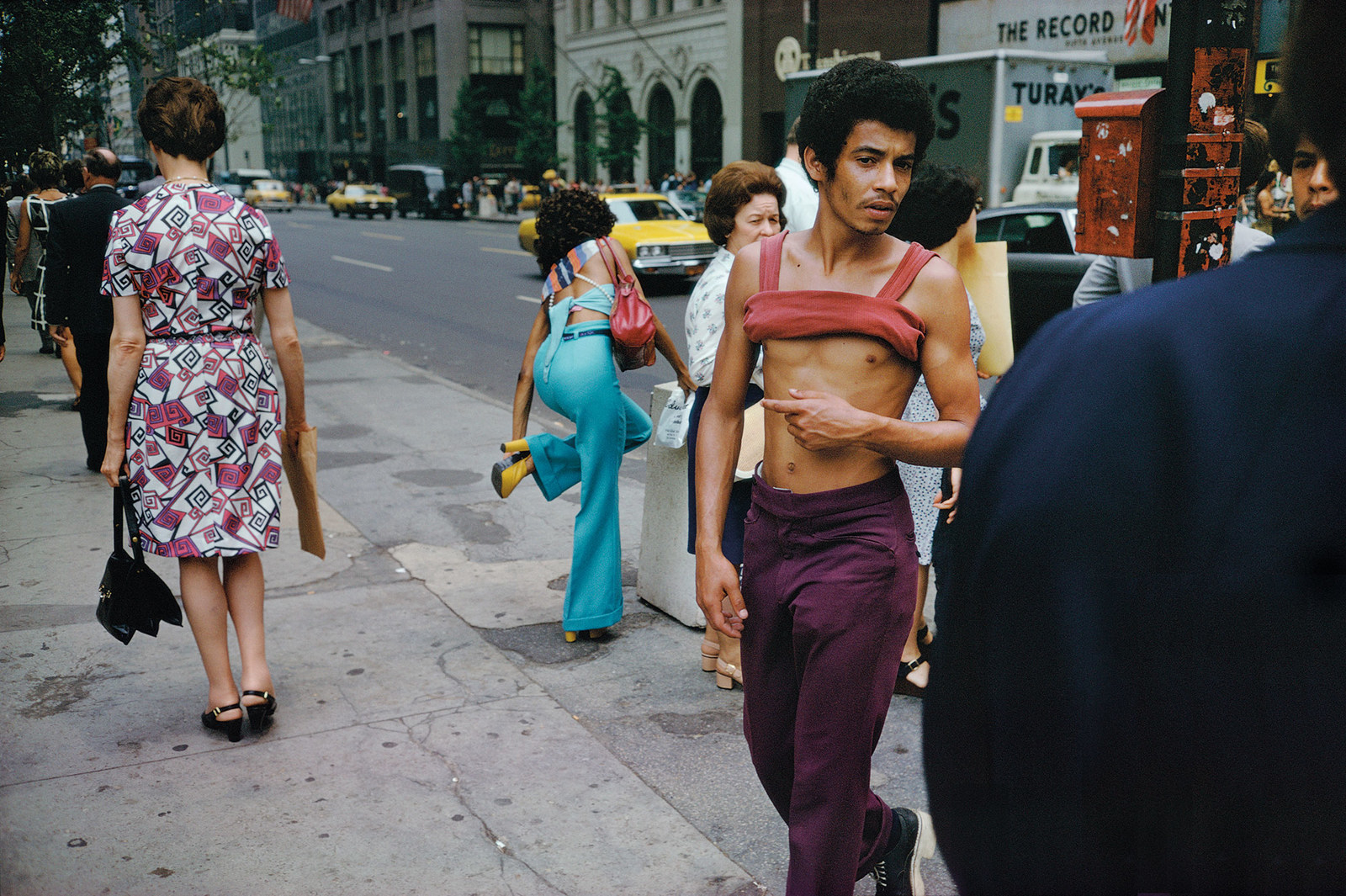

At 80 years old, photographer Joel Meyerowitz has seen it all through his camera lens. In the early 1960s, Meyerowitz discovered his love for making pictures amid the hustle and bustle of city streets, capturing those moments of strange beauty that are often overlooked by hurried eyes. In 2001, he was granted exclusive access to Ground Zero in New York City after 9/11 to document the rescue and cleanup effort following the deadliest attack on US soil since Pearl Harbor.

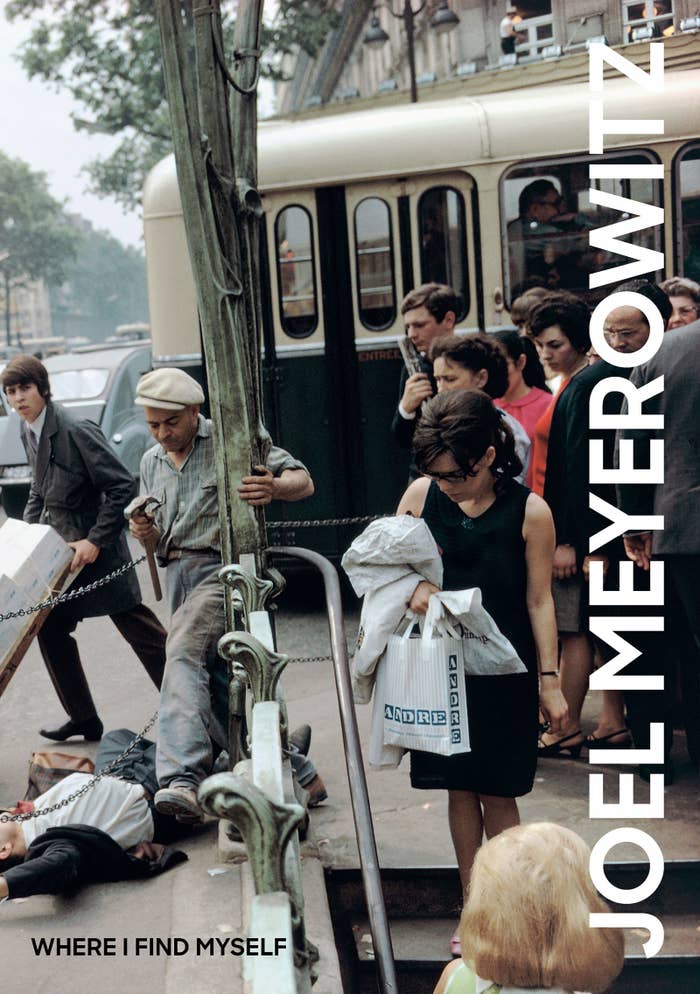

After over half a century of making pictures, Meyerowitz is noted as one of the most influential photographers living today. A new book titled Joel Meyerowitz: Where I Find Myself brings together his tremendous archive to create a portrait of not only America during the 20th and early 21st centuries, but also a prolific artist with a lifetime of groundbreaking work.

Here, Meyerowitz shares a selection of pictures from Where I Find Myself and his musings on photography and art:

How did you begin in photography?

Joel Meyerowitz: In 1962, I was an art director for a small advertising agency and an abstract painter. Art direction was my day job and at night I was often in graduate school earning a master's in art history. I had never thought about photography. But when I saw Robert Frank make some photographs for a job I had designed, I was so entranced by the pictures. All that motion was such a fresh idea to me that once I was back on the street and I saw life moving and scrolling by in front of me, I realized that I wanted to participate in that.

Suddenly, a machine in my hand and the ability to dance on the street, in and out of crowds of people, became like a magical medium for me. I realized that it’s what I wanted — I wanted to be out in the world at large. I wanted to see what was unexpected and try to make photographs of the disappearing, fragmentary moments of everyday life. Suddenly photography became this vast potential of a medium and there were very few people who were taking it seriously. When I started to make friends with other photographers, we all realized that we were on the cutting edge of a new energy coming into photography.

What is the focus of Where I Find Myself?

JM: Where I Find Myself is a retrospective look at 55 years of work. I think it’s important in the course of a book of this length, and after these many years, to be able to show works that are turning points. Not necessarily the most famous images, but the ones through which I learned something so important to my development that it pushed me into the next understanding of photography and the next phase of my work. I think we can say that the focus of this book is about showing the questions that photography raised for my own personal development and me as I tried to answer those questions.

Do you see this book as the story of your life or more of a voyeur's perspective of the world?

JM: The book is more or less the story of how photography has affected my life and has helped me to see not only the world around me but who I was at every developmental phase of my life as a photographer. I think of these pictures really as educational moments of awareness and perception, during which my consciousness about myself in the world was elevated, or guided by the medium itself.

The pictures from Sept. 11, 2001, are some of the most poignant images in this book. How were you able to gain access to Ground Zero?

JM: On the day of 9/11, I was out of New York City on Cape Cod. I immediately packed up my gear and I wanted to return to New York, but I found out that they had closed all traffic in and out for five days. So it was with great impatience that I waited until I could [get] back into New York. I live not far from Ground Zero, so I immediately went down to the site when I came home and stood in the crowds outside of the boundaries. In the crowd, I just raised my camera to take a look and was struck on my shoulder by a police officer who said, “Hey! No photographs, buddy! This is a crime scene!” And when I turned around to argue with the officer, I realized that I was confronting the blankness of bureaucracy.

When I said to her “When is the press going in?” she said, “I told you! No photography is allowed! Mayor Giuliani has banned photography!” At that moment, the light bulb went off over the top of my head. I’m going to figure out how to get to Ground Zero and then contribute all of my work to the people of New York and America for the historical record.

Though some friends, some New York chutzpah, and knowing how to work around anything that gets thrown in my way — you don’t live on the streets your whole life without learning that one — I managed to get a badge and gain entrance. I was the only photographer that had access to be in Ground Zero, and I was there for nine months.

What were some of the challenges you encountered working in that environment?

JM: Really the danger — the enormous danger — and the toxic environment were physical hurdles that were really life-threatening. I can tell you now, 17 years later, that I’ve suffered from it. My breathing is less than it should be. I’m more sensitive to dust, pollen, smoke, and things like that. Even though I wore a respirator and took good care of myself, I spent nine months in a toxic atmosphere.

I also had to overcome, for the first few months, the everyday threat of being thrown out. Fortunately, I protected myself with a team of detectives from the arson and explosion squad who were the only ones who were smart enough to realize that this was a historical imperative and I was producing a record not for personal gain, but for the people of New York. They protected me against the mayor and the police force. So, I have to thank the men of the arson and explosion squad.

Have you kept in contact with these people?

JM: Yes. I knew and still know many of the people down there. Firefighters, police officers, and construction workers — all of us share this experience together and I’m still in touch with a good number of them. For many years, whenever there were celebrations, we would all be there together. I've invited them to openings of exhibitions I’ve had and even sent some of them as emissaries to foreign countries to open exhibitions for me.

In your experience, what makes a good photograph?

JM: I think a good photograph is something that makes you want to pay attention to the information that’s in front of you because of a number of different things — not just a beautiful person in the picture, or a lovely sunset or landscape. It’s not just sheer beauty. It’s a kind of inspired wit, maybe even craziness, that the photographer was aware of in a split second of everyday life. The mind of the photographer grasped the potentiality of the moment to be more than one thing. So they took a stab at it, and what you hold in your hands or look at on the wall is the result of their conciseness, their appetite for life, and their open-minded way of taking the world in.

Is there a specific photograph in this book that means the most to you?

JM: I always like to put that question off, because so many pictures have taught me something in their own way. But I think we can say that the cover photograph of a fallen man in Paris is one of those specific photographs that taught me a lot about how to make a photograph and how to make the most out of a moment that you’re given. But also how the world may view certain moments and what people do or do not do when confronted with that. How a single photograph can carry several different meanings at the same time. I think that photograph does it for me.

What do you hope people will take away from this book?

JM: I hope people will take away from the book an understanding of who I am as a fellow human being and as an artist. I’ve laid out the mystery of my connections, passions, and observations in over 400 pages that show my appetite for life and my curiosity for how oddly beautiful the world is. I hope that people can also see throughout all these pictures that no matter how strange and unexpected the world is, there’s a degree of joy in being alive. I think, for myself, that this is the underlying characteristic of my work. That even in a place as demanding and as dark as 9/11, the joy of being alive in that place and making photographs to keep a record like everything else in the book is the underlying optimistic factor in the work.