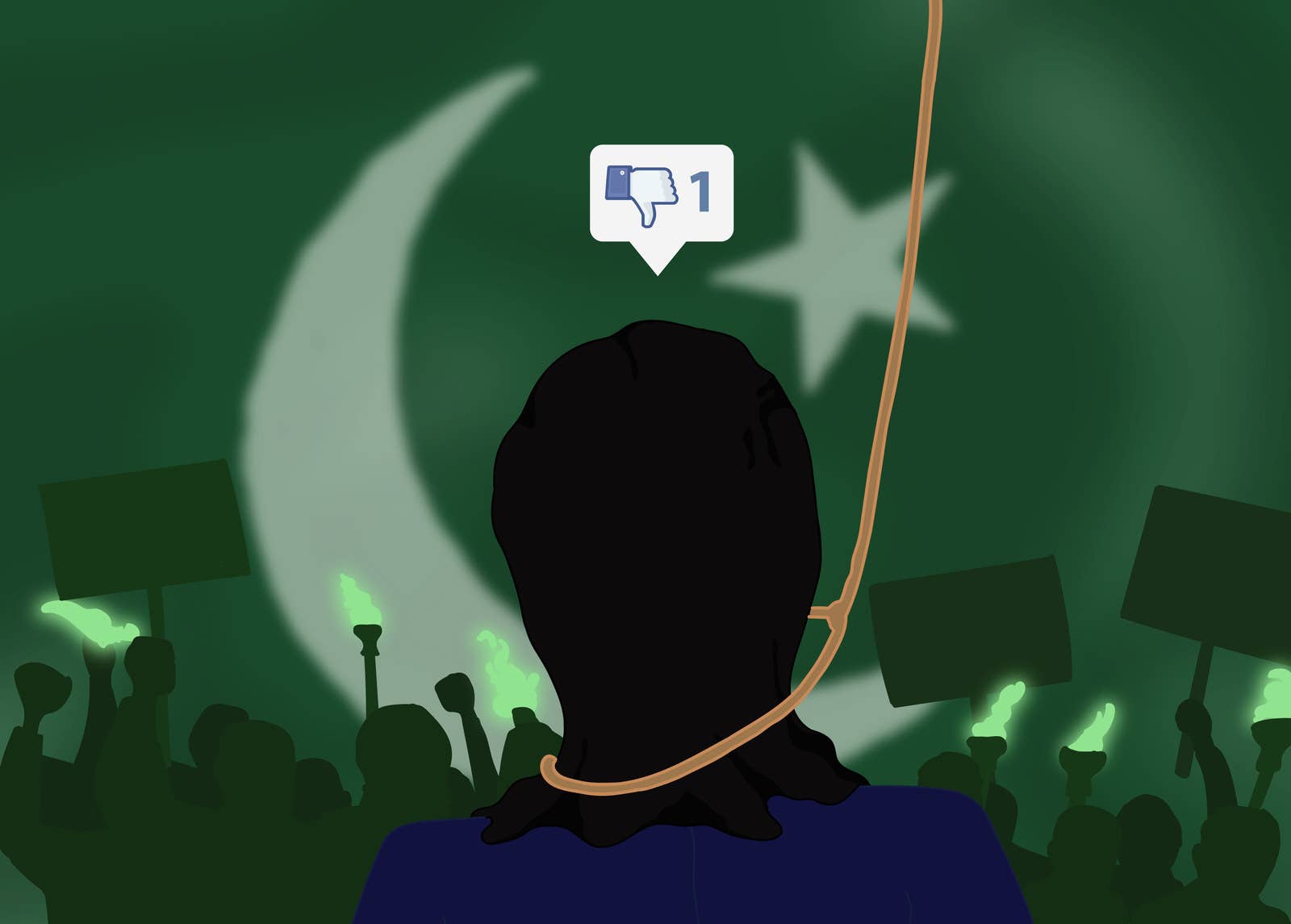

Taimoor Raza is a 30-year-old citizen of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan who now holds the dubious distinction of being the first person to have received a death sentence for making offensive comments on social media.

Where religion and state are not separate institutions, how can blasphemy and sedition truly remain distinct offences?

Raza, a member of the Shia minority, was arrested after an argument on Facebook with a government agent, in which he allegedly used derogatory remarks about the wives of the Holy Prophet (PBUH). The prosecutor has also charged him with ‘hate speech’ against Sunnis, the country’s dominant sect of Islam.

It is difficult to imagine yourself in Raza’s position. At a time when the usefulness and moral acceptability of the death penalty is being questioned across the world, he is now awaiting execution merely for getting into a Facebook argument with the wrong person.

To understand Pakistan's blasphemy laws, it is important to not see Islam as an isolated force, but to understand its relation to the greater political and economic forces governing Pakistan.

Consider for a moment the fact that this death sentence was handed out by the country’s Anti-Terrorism Court. Where religion and state are not separate institutions, how can blasphemy and sedition truly remain distinct offences?

With the public cornered by McCarthyist mechanisms, arrests can now be made for as little as cheering for the enemy’s cricket team, reading a proscribed book, or even posting a potentially offensive comment on Facebook. Among some political groups, blasphemy has been elevated from mere disrespect towards religion, to an act of resistance against the human establishment drawing its strength from that ideology.

To admit that killing someone for insulting religion is wrong, is to invite an accusation of blasphemy upon oneself.

Introduced to the region by the British in 1860, the blasphemy laws were a largely toothless set of rules instituted for the maintenance of social order. In 1986, they were modified to their current Islam-centric form and the death penalty was introduced for those found guilty of insulting the Holy Prophet (PBUH). A law once used to maintain religious harmony had been weaponised by a theocratic system.

Like any other law in a democratic country, the blasphemy laws were once thought to be open to debate and criticism. We were forced to review this understanding of the situation after the assassination of governor Salmaan Taseer, a vocal critic of these laws.

It suddenly became clear that even class privilege did not confer absolute immunity from harm by religious fanaticism. If it could happen to the governor, it could happen to any blogger, journalist, or Facebook commenter.

After Taseer’s murder, a line was drawn in the mind of every average Pakistani.

This is what got someone killed, so this is what we mustn't say.

However, as citizens continue to get lynched or sentenced to death under pretexts that get flimsier by the day, we’re gradually losing the vocabulary with which to state our case.

In Raza’s case, the national media too has remained suspiciously quiet. It is not clear whether this silence signifies apathy, fear, or fatigue. Perhaps the media too has run out of words that are safe to use.

The solution isn’t as simple as to ‘not blaspheme’, because there is no objective line between criticism and sacrilege. What one may consider benign, may be regarded as ‘blasphemous’ by another; often posing grave risk to activists or writers like myself.

And once you have been accused, like Mashal Khan was, there’s no guarantee that one would even live to see the inside of a courtroom.

In April this year, Mashal, a 23-year old student, was seized by a mob and killed for blasphemy. Moderate Muslims unanimously condemned this act. The general opinion at the average dinner table around Pakistan was that those accused of blasphemy must not be killed — extrajudicially.

By saying nothing more, a majority of moderate Pakistanis – including our dependable liberal figureheads – implicitly supported a dangerous message: that killing someone for offending someone else’s religious sentiment isn’t inherently problematic; that Mashal’s death was regrettable collateral damage in an otherwise worthy war against blasphemy.

This time there is no mob of reactive brutes for us to blame, or a lone fanatic for us to admonish. A man is to die in the name of religion, not at the hands of an impulsive radical, but by the long, calm, and cold contemplation of the court.

The defense attorney continues to maintain that his client is innocent, and activists like Jibran Nasir have highlighted significant legal problems with the handling of the case. But the problem lies precisely in our reliance on the technicalities of the law.

After Taseer’s assassination, moderate Muslims made the tactical decision to condemn the nature of the killing, rather than killing itself; resting their hopes on loopholes in the social and legal order to rescue specific individuals caught in the trap.

“Blasphemers must be killed, of course,” the message went out. “But not Mashal. Not Taimoor. Not Taseer. Not Aasia Bibi. Those particular ones were innocent and wrongly accused.”

Taimoor Raza’s death sentence rubbishes the common notion that religious extremism is firmly contained within a fringe minority. Although some institutions are more blameworthy than others, when a democratic state executes a person, it is the people who must answer for their beliefs and values. Suddenly culpable, at least in part, is your aunt, and my friend, and the shopkeeper down the road and the woman who cooks my food, all of whom believe that blasphemers must be punished. Somehow, I’m part of a lynch mob now.

To reach into one’s moral core, and admit that killing someone for insulting religion is wrong regardless of the circumstance, is to invite an accusation of blasphemy upon oneself.

Unfortunately, we’re running short on excuses to avoid stating the obvious.

We are left with no choice but to be honest about our identity and our objective. We must determine whether we are followers of a peaceful religion, or people who advocate death to those who disrespect our faith. One cannot be both at the same time.