The 4th Annual Philadelphia Police and Firemen Wing Bowl will start an hour late. Five inches of late-January snow have piled up outside, and the guest of honor, national speed-eating champion Takeru Kobayashi, is en route from New York, delayed by the weather. Husky servicemen and their families trickle into the banquet hall slowly as Carly Rae Jepsen's "Call Me Maybe" blares in the too-bright room.

People load up on the buffet — foil pans of hot wings under heat lamps, shiny hot dogs spinning on steel rollers, bowls of blue cheese sauce partially covered in plastic wrap, and one sad bowl of carrots that remains largely untouched. One guest stands up from his table, turns away from the crowd, lifts his shirt, jabs an insulin needle into his stomach, then sits back down in front of a plate of two hot dogs. There's no sign of Kobayashi, or of the vat of wings he's been asked to devour in front of the crowd. He's not being paid for this appearance; event proceeds benefit the families of police officers who have been killed in the line of duty.

Finally the lights go out in the dining hall. Spotlights whirl around the room as the DJ does his best sports-arena announcer voice to welcome the 35-year-old, 132-pound Kobayashi, who is ushered in by five leather jacket-clad police officers that, forgive me, look like Tom of Finland illustrations come to life. Kobayashi will first watch the policemen's contest, standing at the head of a long row of tables where 10 competitors — all men — are ready to eat as many wings as possible. The clock starts; what ensues is horrifying. The people who were actually eating the wings had no chance in the contest. The guys who came out on top did so by dipping and smearing, pulling meat off the bones with their teeth and shoving it down their throats like you'd put trash in a disposal. The one who's winning is standing up and wearing headphones, his shirt covered in sauce. It's clear that he's the only one taking this seriously.

"Kobi doesn't eat like these people," says Maggie James, Kobayashi's manager, translator, and girlfriend. "When he does it, it's almost like art."

Next, Kobayashi finally sits down at the stage for the main event. He's paired with the chief police inspector, and the two of them battle four members of the Philadelphia Fire Department to see which team can eat the most wings in five minutes. The soundtrack to the carnage is "Hey Ho" by the Lumineers, which the DJ plays for nearly the entire duration of the eating contest.

It is less disgusting when Kobayashi speed eats, partly because it's just much faster. James shouts encouraging things at Kobayashi in Japanese as he eats alongside the police chief, who's barely even trying. About a minute in, one of the event's publicists jumps on stage and yells, "Photobomb!" and poses behind Kobayashi.

Kobayashi would love to go gullet-to-gullet with other professional eaters, young upstarts who have studied and improved upon his philosophy and methods, but he believes that would mean ceding control of his career, of his very particular, peculiar talent. So instead he competes against patsies, but really, he's just competing against himself.

After the contest, before the wings are counted, Kobayashi seems concerned about something. Kobayashi calls James over to point out that his team was given only drumettes while the other team had only flat wings, which are easier to eat.

In the end, Kobayashi and the police chief did beat the four other guys, of course, but James seems frustrated that he was made to do it the hard way. Although by now, Kobayashi should be used to doing things the hard way.

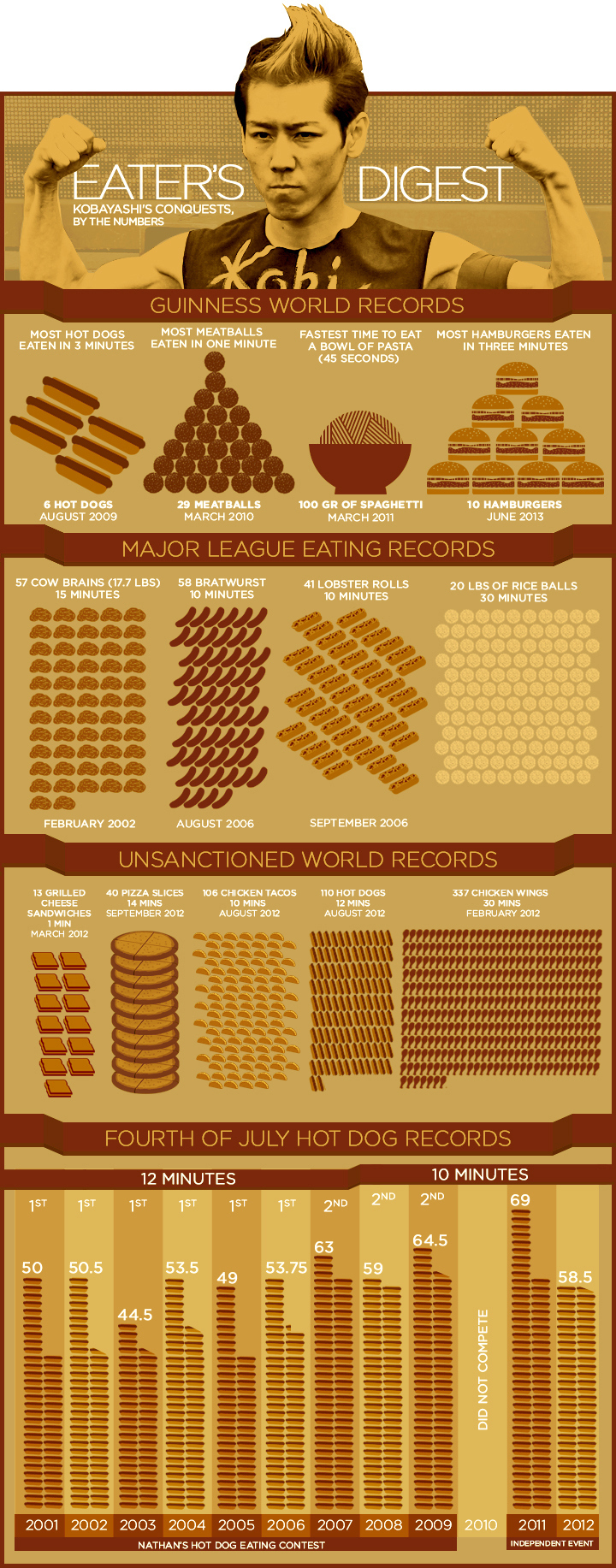

The competitive-eating circuit, the flagship of which is the July 4 hot dog-eating contest at Nathan's in Coney Island, existed before Kobayashi. But when he first competed there in 2001 at age 23, he inhaled 50 wet, mangled franks and buns in 12 minutes — more than double the previous record, spurring accusations that he'd used muscle relaxers or had some sort of stomach-expanding surgery. He made it harder to dismiss the idea that people doing something this patently silly could be considered professional athletes. (He'd discovered his talent superhero-origin-story-style, at a restaurant near his college in Yokkaichi, Japan, years earlier, eating 20 pounds of curry rice in 11 minutes.)

"I think I stuck in people's minds because I was slim," Kobayashi tells me, through James. "And suddenly the next year, for the first time ever, there were other people with my physique who wanted to be in the contest. You could see it gradually getting bigger and bigger."

Aided by Kobayashi's celebrity, ESPN began airing the Nathan's contest live in 2004. George and Richard Shea had parlayed their long relationship as publicists for the Nathan's contest into the tongue-in-cheek yet business-savvy Major League Eating (née International Confederation of Competitive Eating), brokering contracts between the eaters and corporate sponsors.

Over the next six years, Kobayashi set records for speed eating hamburgers, lobster rolls, cow brains, Chinese dumplings, pork buns, and bratwurst in contests all over the world. In 2003, he appeared on Fox's Man vs. Beast to eat hot dogs in a timed contest against a bear (the bear won). In Japan, his face covered magazine newsstands. He accumulated groupies who followed his contests and his blog obsessively. His nickname in the press became "The Tsunami," based on the wave he makes when he shakes his body to get food down faster.

The phenomenon came with a physical cost: In 2001, Kobayashi developed a stomach ulcer after a curry rice-eating contest in Japan and was rushed to the hospital the next day. Now Kobayashi says he doesn't eat spicy food very much at all. In June 2007, a few weeks before the first Nathan's contest he lost after six straight wins, Kobayashi developed jaw arthritis.

The doctor who treated his ulcer noticed that when his endoscopic camera touched Kobayashi's stomach, the wall expanded abnormally quickly. But Kobayashi doesn't think there's anything special about him physically, except that his stomach might be naturally very elastic.

"The one thing that's broken inside of me is that I've lost the signal most people have to feel hungry or feel full," he says. "I could easily go one or two days without realizing that I'm so, so hungry. That's the negative outcome of what I've become."

Then things got messy: In 2010, following three consecutive years of losing at Coney Island to new sensation Joey Chestnut, Kobayashi refused to sign a contract with MLE, saying it limited his ability to make money because he couldn't compete in other events or negotiate his own endorsements. Kobayashi rushed the stage after Chestnut won, wearing a "Free Kobi" T-shirt, and spent the night in jail. Speaking to the New York Post, MLE's CEO George Shea called it an act of desperation because Kobayashi had lost three years in a row. With that, Kobayashi became persona non grata to the MLE, but he soldiered on independently of the league, making a living through paid appearances and setting Guinness World Records, out of official competition.

MLE removed his portrait from their Wall of Fame. The New York Daily News called him a "whiny weiner lover" when he failed to set a new world pizza-eating record and reportedly blamed the pizza. In 2011, when Kobayashi staged a July 4 exhibition from a Manhattan rooftop at the same time as the Coney Island contest, Chestnut said: "If he wants to compete with me on the 4th of July, he knows what he has to do: Sign a simple contract and man up."

He will not sign the contract, but he is manning up: On July 4, 2013, Kobayashi will hold court at his own event — not a solo sideshow exhibition, but a grassroots alternative for non-MLE eaters. "It's very necessary for competitive eating to be more than that one contest we all know in Coney Island," James says. "Kobi's wish is to make this big."

It's September 2012 and Kobayashi and James are visiting the BuzzFeed offices with news they believe proves that leaving MLE and Nathan's was worth all the bad press: He'll be the spokesperson for Hofmann's Hot Dogs, a 133-year-old family-owned sausage company operated out of Syracuse. For someone who cannot really speak English, he's an eager spokesman.

Hofmann's had recently been purchased for $7.5 million by an investment group led by Frank Zaccanelli, the former Dallas Mavericks president and real estate mogul who grew up in Syracuse. Zaccanelli convinced Hofmann's fifth-generation owner Rusty Flook to sell, announcing plans to take the brand national. (Among the other investors: the Oneida Nation, legendary former Dallas Cowboys quarterback Roger Staubach, Syracuse basketball coach Jim Boeheim, and a former Syracuse police chief.)

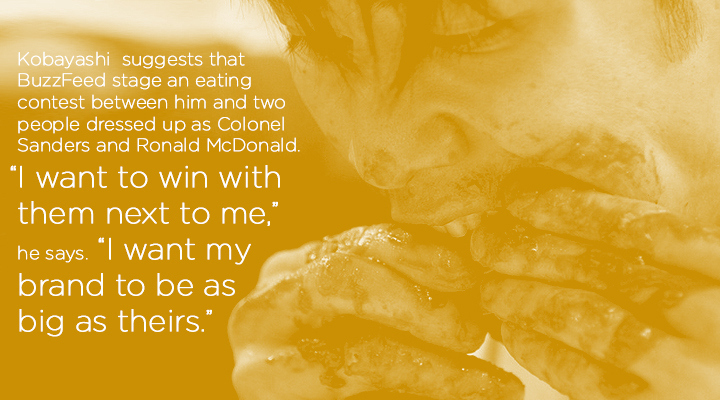

Kobayashi is excited. He talks at length — through James — about the quality of Hofmann's sausages and how long he has dreamed of having his own signature hot dog, which will be called either the Kobi dog or the Kobayashi dog. Before he leaves, he suggests that BuzzFeed stage an eating contest between him and two other people dressed up as Colonel Sanders and Ronald McDonald. "I want to win with them next to me," he says. "I want my brand to be as big as theirs." The Hoffman's deal is lucrative, and flattering, to be sure, but above all else, it's a vindication.

"We did some research to find out the kind of exposure he provided Nathan's," Zaccanelli says over the phone a few days after Kobayashi's visit. "When Kobi got involved with them, they were in 20 states. Now they are a huge national company with a big footprint. He will do things for us like we recently did with the New York State Fair, where people can witness him break the world record. He'll do the Texas State Fair and will be judging a hot dog-eating contest between fraternities at the University of Texas and Oklahoma, then he's going to put on a five-minute eating exhibition."

Also on the call is Phil Romano, a Dallas-based restaurateur who started several successful national chains including Fuddruckers and Macaroni Grill. "I'd like to get this down to the size of a Subway so we could put it just about every place, near colleges, to get the young people eating the hot dogs," Romano says.

In return, Kobayashi will receive $100,000 as an annual salary, 2% of supermarket sales of all Hofmann hot dogs, and a stake in Hofmann's Hots, the restaurant chain that the investors plan to open nationwide, starting in Dallas. All of this feels like a step up from being paid a reported $3,000 to eat a pizza in under a minute at a fraternity Super Bowl party. ("His income is coming primarily from appearances," says James, who has taken a salary as his manager since 2010.)

Kobayashi also worked with Flook to design a special limited-edition hot dog specifically for competitive training: thinner and longer, closer to a standard supermarket hot dog in size and composition than Hofmann's sausages. "Kobi calls it the 'sports dog,'" Flook says. Its secret — perhaps for good reason — recipe mimics the oiliness of hot dogs used in competitive eating contests. "It's not really oil, it's the fat content, which makes it slide easier because he's not chewing these."

Four months later, Kobayashi and James are having lunch at the Le Pain Quotidien near his apartment in Chelsea. He's wearing a print cardigan made by Roberto Cavalli and tight black jeans. She's wearing high-waisted black slacks, heeled booties, and a bright blue-and-red, polka-dot scarf. They look happy and relaxed. They just returned from a weeklong trip to Turkey, paid for by a Turkish television network, so Kobayashi could attempt to break his own Guinness world record for hamburgers.

"When they said they wanted him to do hamburgers, Kobi was like, 'Can I do another one? I already have that record.' But they insisted," James says as they order. "Of course, we got off the plane and they picked us up at the airport and were like, 'By the way, our country is at war.' Our two best friends in Turkey who we went to see, one of them was out on the front lines wearing a gas mask."

The couple met in Tokyo in 2008 and instantly became best friends. (Her mother and aunt were already Kobayashi groupies, following him to events.) "I was hosting this gay male party and I invited Kobayashi to come because I thought he was gay. He shows up and says, 'I don't think I'm gay,' and I'm like, 'What does that mean, you don't think?' He's like, 'I don't know, everybody all my life has told me that I'm gay, but I've never experienced that.' And Kobi is just a little bit strange, so people think that, but when you get to know him and talk to him, there's nothing really feminine about him."

In 2010, after they'd been dating for six months, Kobayashi told James he was moving to New York. "He does what he wants, so there was no conversation, no consulting. He didn't ask my opinion at all. He said, 'I'm moving to New York, bye.' I gagged. I was like, 'What do you mean? This is a relationship; we discuss things.'" A year and a half after Kobayashi moved to New York, James moved too. (When I ask him why he loves living in New York despite how expensive it is, he says, in English, "Because there are so many dogs and they are so cute.")

James is 36 but looks a decade younger. She keeps her own apartment in Brooklyn but spends a lot of time at Kobayashi's place in Chelsea. She has a full-time job designing jewelry for Ranjana Khan but sets Kobayashi's schedule and handles all of his communication with clients and press. "I wasn't even his manager at first," she says. "I was his stylist. My goal in life is not to be Kobayashi's manager."

January to April is slow every year, she says. "There's almost nothing, especially this year, maybe an appearance once a month. But then it gets crazy busy in the spring, and I'd say we have six or seven appearances a month, and tons of interviews. And then you have the training. That never ends." As we talk about training, Kobayashi's quinoa salad arrives. He pulls out a camera to take a picture. "He's such a foodie."

Kobayashi says food is only a very small part of his training process, although he is purposefully vague about the specifics and will not be around people during the thick of it. He primarily uses water to expand his stomach. "I know I am ready for competition when I can drink three gallons in a minute and 30 seconds," he says through James. Working up to that point takes weeks.

I ask Kobayashi if he wants more work and if he feels he is making enough money. As usual, when I ask a question, he looks to James to translate. "You know how to say that," she says. I can tell he understands most of what I'm saying. "I think I'm stable," she says, speaking as him. "He says, 'I feel like I'm not too busy, I would appreciate even more work.'"

As James translates for Kobayashi, she switches from first to third person often, and it's hard to tell where his words end and hers begin. But that doesn't seem to bother either of them. Nor does the criticism, lobbed by some in the MLE circle, that his refusal to sign a contract and subsequent alienation from the organization may be the result of advice on her part.

"I'm not going to say anything bad about his girlfriend or manager, but I don't think she's good at negotiating on his behalf," Joey Chestnut says. "MLE is a pretty small organization and she has to understand that she has to play ball. Be willing to give and take."

"There's not a bone in Kobi's body that cares about money," James says, insisting that the contract decision was all his. "He wants freedom. But he's also not a stupid person. The amount of money that they were offering him in that contract was not enough to be able to own somebody for a whole year."

Kobayashi says MLE offered him a $25,000 contract to appear at four events in 2010. If he won all of the events, he could make up to $100,000 and he could not compete in any other events or endorse any products outside of MLE. Negotiating, he asked to be contractually obligated only to the Coney Island contest, and to be free to compete, participate, host, judge, and endorse outside of the league. Instead, MLE offered him $40,000 to compete in only two Nathan's July 4 contests in 2010 and 2011, but insisted on exclusivity. Meaning, Kobayashi's guaranteed salary from anything related to competitive eating would be $40,000.

MLE was still emailing James at 2 a.m. the night before the 2010 contest, begging her to get Kobayashi to sign and to show up. "Kobi goes, 'Write them and say I don't want any money," says James. "I'll be in it for free. You get your press, I get my press, I eat hot dogs. And then I get to have my own thing and be a free agent.' And they wouldn't do it. That's when Kobi was like, 'OK, it's not even about money to them, either.'"

Richard Shea sees it differently: "We have contracts with all the eaters because we have the biggest events with the most prize money. You cannot go compete on the 4th of July in Nathan's contest and the very next day win a different hot dog brand's contest. Nathan's and broadcast television spend a lot of money to make that the biggest day of the year."

Kobayashi's sticking point wasn't just about doing other contests. He also didn't want MLE negotiating his sponsorship fees with corporate brands. "It said in the contract, 'If you win, you have to hold the Pepto-Bismol in your hand for the press, or you have to drink it all down,'" Kobayashi says. "They have that in everyone's contract, so it doesn't even matter who wins. That's an endorsement for Pepto-Bismol and the athlete should be getting something."

In the three ensuing years, no middle ground has been reached. If anything, Kobayashi is feeling more emboldened, even without the mass exposure that a holiday audience on ESPN can provide.

"My motivation is higher than anyone else's," Kobayashi says as he finishes, slowly, his modest quinoa salad. "If they are in the MLE, they have all these things between them and the top — they're not able to get bigger. For me, I can feel how if I've done something good, I can benefit from it directly."

"The league's growth was not stunted by his departure, I'll be honest," Richard Shea says. "We always want Kobayashi to come back and try to win again, but we're also doing incredibly well." The ESPN audience for the Nathan's contest has grown nearly every year. Last year 1.9 million people tuned in to watch, and the current contract runs through 2017.

This is thanks in large part to the emergence of homegrown talent like Chestnut and 21-year-old Matt Stonie, both of whom happen to live in San Jose, California. To them and other competitors, Kobayashi is both an inspiration and a cautionary tale. Because while the eater elite may have figured out new and better ways of cramming food into themselves — and keeping it there — the concept of career longevity is still an alien one, and Kobayashi's exile hasn't exactly rallied his eater brethren to the cause.

"The younger you are, the more your body can tolerate this stuff," says Stonie, a rising star in the competitive eating world. (Currently No. 4, to be exact.) Stonie, who recently set a world record by eating an entire 5.5-pound birthday cake in just under nine minutes, is at Mission College in San Jose, where he's studying...nutrition. "A lot of people think a nutritionist would be against what competitive eaters do, but it helps to understand how the body works. I'm training like any other athlete would train for a sport. It's just repetition, increasing stomach capacity. I'm in the best shape of my life. No one has really done studies on competitive eating, no one knows what works, so most of training is either word of mouth — which you're getting from your competitors, so you have to take with a grain of salt — or just finding out what works for you. There's no resources because MLE doesn't want anyone to have anything to do with home training."

Therein lies the question that is in many ways the root of Kobayashi's dispute with the league as exposure and revenue increase: Does the MLE have an obligation to look out for the best interests of individual eaters, or do the eaters serve at the pleasure of the governing body? The Shea brothers need to tout competitive eating as a sport to bring in fans, sponsors, and money, but that suggests the athletes train, which is a liability. "I'm not a big fan of training," Shea says. "I don't want someone in their basement eating a bunch of hot dogs." MLE does not provide insurance for their athletes; they buy insurance for their events and have paramedics standing by. Calling it a sport might also mean acknowledging that this is a proper career for the athletes, that the eaters' lives are not normal, and that the money they make needs to support their routines full-time.

"I bet if you talk to the balance of the eaters, they are doing it for fun," Shea says. "For many people it's about the thrill of the event, being on TV, and getting a crowd reaction, because day in and day out your life is like normal."

But even to a relative newcomer like Stonie, that's already not the case. To him, "going pro" means, "You earn a good amount of money, you travel, and you just don't do it just for fun anymore," he says. "I love doing what I do, but I put myself through a lot of stuff to get where I'm at."

As the top-ranked eater in the league, Joey Chestnut makes enough money through MLE appearances and contests (about $160,000 in 2012 and $220,000 in 2011) that he was able to quit his job in construction management; he believes all this gives him a distinct advantage to remain top-ranked. "I'm able to put all my time into it," he says. "Whether I'm drinking water in the morning, fasting, protein supplements, my diet is 100% dedicated to my practices." Chestnut goes into each practice with a completely empty stomach, having fasted for two and a half days — just a half gallon of water and a half gallon of milk to stretch the stomach muscles. This is not the kind of lifestyle he envisions long-term.

"I'm turning 30, and this year was definitely harder than four years ago," he says. "I really have to develop an exit strategy." He's working on opening a beachside hot dog bar with a friend in Clearwater, Florida. "It's a lot more work than we thought it would be, but we got the menu done, Nathan's is on board, and I love Nathan's hot dogs." If that doesn't work? "I'll go back to construction management. I mean, I still lead a pretty normal life, other than the travel. There's people in the world who work harder than me who get paid less. In the grand scheme of things, we're going onstage and eating."

Unlike his would-be archrival Kobayashi, Chestnut has no problems with his MLE overlords and understands that his particular skill set might be of little use without them. "They run decent events, they do all the work, they find sponsors — I don't want to find sponsors. I'm a competitive eater, I'm going to go there and eat. I kind of agree with [Kobayashi] to a certain degree: He doesn't want someone to tell him what he can and can't do. But I don't know exactly what freedom he is really looking for. He really hasn't done that much since he left — a couple Guinness things, competing against nobody, competing against himself. Nathan's was a big part of his life, and I'm surprised he'd try to make it seem like it was small."

Stonie, who started his career after Kobayashi left and thus has never competed against him, is also less than awed by the ex-champ's legacy. "He obviously changed the sport, brought it into the mainstream media, and he's great for that," he says. "But the truth is, Joey beat him three times in a row. He's a great eater, I respect him, but I don't think he's the best."

Chestnut would like to see the conflict reach resolution — for the good of the sport. "It would be the best thing for him, for me, for competitive eating," he says. "You can only be so angry for so long, you gotta move on."

In January, Kobayashi and James flew to Syracuse for a meeting with Hofmann's. Legendary art director George Lois was supposed to come the next day with his PR people to do an execution of the logo, the branding of the Kobi dog, and Hofmann's was planning a $500,000 national TV commercial to come out in May. But Kobayashi and James weren't allowed to check in to their hotel. They were told by Hofmann execs to wait in the lobby, where they sat for six hours.

Zaccanelli finally arrived and explained the ugly truth: The investors were suing Zaccanelli, accusing him of using company money as a personal slush fund for an employee they said was his girlfriend. The accusations were juicy: That he gave her a job at the company, used company money to pay for her apartment, and made Hofmann's employees backdate her employment records so that she could receive company health insurance. Zaccanelli denied it all, but Kobayashi and James weren't fooled.

"She's controlling Zaccanelli," Kobayashi says in choppy English.

"She was killing us," James adds. "He's looking at us and saying, 'I can't believe they're accusing me of this,' and we're kicking each other under the table thinking, Everyone knows you're having an affair with her. She's been the death of this company. [Kobi's] entire schedule for 2013 was ambushed by that; we had canceled so many clients to put Hofmann's in priority."

Zaccanelli resigned and settled the lawsuit. He denied both the financial and romantic allegations, telling the Dallas Morning News that he has been "happily married for 30 some years," but said he wanted to avoid dragging out a fight that would hurt the company in the long run.

Kobayashi was not named as a plaintiff in the lawsuit, but his contract was with Zaccanelli Food Group, not Hofmann's, so his deal was dead. "I thought, strange how disposable I am," says Kobayashi. "At the end of the day I just want to sell my own hot dog."

It's five days before the 4th of July and Kobayashi is deep into training to set a world record that may not be recognized by any official sanctioning body. He knows he's ready because he can drink three gallons of water in a minute and 30 seconds.

We are in the garden of Kobayashi's favorite restaurant, a rustic Italian spot in NYC's West Village called Palma. Kobayashi is not eating, of course, but is concerned that the Prosecco will go flat and the food will get cold before James and I have had a chance to taste it all.

Instead of stressed, Kobayashi seems…fine. And yet in a few days, he will compete in a hot dog contest against seven other people at the Eventi Hotel in Manhattan, 13 miles from the ESPN cameras and crowds at Coney Island. The names of the seven opponents are not listed in the event's press release, but James insists they're legitimate competitors, not firefighters goofing off for charity. "They're huge eaters, they're badass, they're no less than the ones onstage in Coney Island," says James. "The only difference is that they also don't want to sign that contract." The long-term goal, as far as Kobayashi is concerned, is for sponsors and eaters alike to see that there's a future for these kinds of events outside of MLE's domain.

For the first time in all of our conversations, James flat-out refuses to translate for Kobayashi. "He understands everything," she huffs, acknowledging that he'd be better at speaking English if she weren't around. (Joey Chestnut posits that the language barrier has damaged Kobayashi's marketing potential.) "I can't speak English. I'm difficult to understand," he says, slowly and pained.

Kobayashi immediately gives up lapses back into Japanese, and James reluctantly translates: "At Nathan's, I wasn't even nervous anymore. I just showed up to eat. Now, we make the events ourselves, and I worry: Are people going to come to see me? Will press think it's dead? Will sponsors be happy they paid for it?"

This 4th of July, many of Kobayashi's closest friends can't come. "We have a group of people who are always here, every year," James says, listing names of friends and family who wore "Free Kobi" T-shirts and lifted him onto the stage in defiance of Nathan's the year he was arrested. Some have moved back to Japan, some have work or personal commitments. "People are getting older," says James, who misses her friends and the way they helped her put on the show. "It's going to be so fun, with, like, a fancy VIP area upstairs. Kobi will be downstairs with all the beer and hot dogs, of course," she says. "I am always in the front of the stage. Until it's over."

His goal is to eat more than 70 hot dogs — he's done it more than half of the time in his training sessions. But due to Guinness' convoluted and restrictive rules for eating contests — utensils are often required, which isn't generally how pro eaters roll — it's unclear who would officially honor or verify this milestone if it were to occur. The audience may be in it for the animalistic spectacle, but Kobayashi needs the validation of the numbers.

"He won't live, he won't go out with us if he's going to go into a competition," James says with a sigh. "He's so focused, it's hard for us. He is so extreme about what he does, if he isn't in the right condition he's upset with himself."

"Actually, I'm not as extreme as I used to be," he says, "and I think that's why I'm able to keep doing it. If I was as extreme as I was when I was younger, it would be too much stress for me to do it at this age and live the life I'm living now."

And just as important as a potential new record or sowing the seeds of a renegade circuit is the fact that this event, sponsored by a New Jersey-based hot dog company called Rastelli's, will serve as the de facto launch for its new Kobi dog, which will be available online starting on July 4, then will gradually roll out to supermarkets and restaurants.

"He went back to his roots and went indie all the way," James says. "The contract is so simple, every single detail will be discussed together, we make decisions together. We're just selling the Kobi dog and we'll split it 50-50 with the Rastellis. It was so painful when [Hoffman's] fell apart, but I think this is better." The botched Hoffman's deal was astronomical by comparison and allowed for appearance fees and high-profile commercial campaigns, but, clearly, mo' hot dog money, mo' hot dog problems.

"All those things seemed so big," Kobayashi says, "but now it seems like there was so much that came with it."

Still, though, that kind of autonomy remains the end game. "Kobi as a brand should be big enough so that he can make money without eating. He deserves to have a product," James says. "If he needs to spend another five years eating to be able to have money coming in until he dies, that's what he's going to do. If he quits now and it goes down the drain, then I would feel very sorry for him."

Of course, Kobayashi is ready to do it the hard way. "I am still the best competitive eater in the world," he says. "My record for hot dogs is incredible and improving. I will still be eating five to ten years from now when the rest of them have to physically retire. They'll be like, 'Oh, he's still eating? How can he do that?'"