Steven Shipman is minutes away from his first ever court appearance. The 32-year-old has never been in trouble before but four months ago he was caught driving with cannabis in his car. Now he finds himself in Sheffield magistrates’ court facing charges of possession and driving under the influence of drugs. The situation is already enough to make anyone nervous, but Shipman has further reason to dread the hearing: He has no lawyer.

Shipman earns a modest wage as an agency chef and his partner is on similarly low pay, working in a warehouse for Asos. Their combined annual income is roughly £24,000, which leaves them with about £40 to spend a month after bills, food, and rent. It also makes them too rich to get free legal advice.

“I feel it’s unfair because if I’d have been unemployed I’d have got legal aid,” he says. “I wasn’t particularly aware of legal aid until I needed it. I was a bit shocked about it because I was under the impression I’d qualify. Neither of us are on fantastic incomes.

“I’ve got some debts and my partner has as well, which means I can’t afford private fees. It would have been £350 plus VAT, which is not something I’ve got lying about.”

BuzzFeed News has been documenting how legal aid cuts have undermined the civil and family justice system in England and Wales. Now damning new research shows that, even in criminal court, growing numbers are facing prosecution without a lawyer.

An exclusive survey of magistrates for BuzzFeed News by the Magistrates Association shows more and more people are facing criminal charges in court without a lawyer. The figures expose the true scale of the problem, as the Ministry of Justice does not collect its own data on the issue for magistrates’ courts.

BuzzFeed News can reveal:

Magistrates report that the number of people appearing in court without a lawyer has risen by a quarter in three years. The survey found that 30% of all criminal defendants they saw at their last session had no lawyer, up from 24% in 2014.

The problem even extends to crown courts, where the most serious cases are heard. More than 6,000 people appeared in crown court without a lawyer or had unknown representation at their first hearing last year – that’s 7% of all defendants. In 2013 this proportion was 5%.

94% of magistrates believe that having people in court without lawyers can have a negative impact on the effectiveness of the court process. This figure has stayed the same since a survey in 2014, suggesting little has improved in the experience of defendants without lawyers while their numbers have risen.

Of the 370 magistrates surveyed, 40% said having no lawyer had a bad impact on effectiveness in most or all cases. A further 53% said it did so occasionally.

In more than 160 anonymous written submissions, magistrates’ concerns include that defendants without lawyers are being found guilty of crimes they did not commit and being sentenced too harshly.

Cases witnessed and interviews gathered by BuzzFeed News over several days in Sheffield magistrates’ court reveal that many of those facing criminal charges alone have serious mental health problems and could never afford a lawyer.

Experts say the situation makes a mockery of Britain’s proud justice system. In the US, for example, the right to a defence lawyer in criminal cases is the sixth amendment to the constitution.

In his first interview since being voted in last month, the chairman of the Magistrates Association, John Bache, told BuzzFeed News there was “a real anger” among magistrates about the rise in people being unrepresented in criminal cases as a result of legal aid cuts.

Bache said he was “hugely” worried that defendants were not getting a fair trial.

“People are finding it more and more difficult to get criminal legal aid,” he said. “Rich people can get legal advice by paying for it, but the poorer defendant, of which we have a fair number in magistrates’ court, aren’t going to get a fair crack of the whip. They’re not being fairly treated, through no fault of the court. It’s had a detrimental effect on the fairness of the process and the efficiency of the process.

“If you have a criminal record as a result of an unfair process, that’s going to have a negative effect on a lot of aspects of your life, both personal and professional. If you’ve got an unfair criminal record, that shouldn’t happen whether it’s for shoplifting or murder. You’ve got to have a fair hearing no matter what the offence – that’s the most fundamental principle of British justice.”

He called on the Ministry of Justice to fix a a “very real and genuine problem which is affecting defendants, some of whom will be not guilty of the offences of which they’re accused”.

Bache added: “There is real anger. Magistrates are, by definition, fair-minded people and if they see an unfair process going on they’re going to be angry, particularly if it adversely affects the most vulnerable, and that’s what’s happening... That’s why magistrates are so annoyed about it, and they’re very limited in what they can do to address the problem.”

Several decades of cuts to criminal legal aid have been compounded by a failure to update the means test to reflect current wages and the cost of living, leaving those on low incomes with no chance of legal help.

Lawyers and magistrates say that an increasing number of cases are also being turned down for legal aid over a subjective “interests of justice” test. This used to be decided by court staff but has now been outsourced to call centres run by the Legal Aid Agency, a theoretically independent body that is part of the MoJ. One legal adviser to the court said she had seen cases involving serious charges, such as carrying a bladed article, refused. A defence lawyer said he knew of domestic assault and burglary cases going undefended because of legal aid refusals.

In astonishingly frank anonymous testimony submitted to their association, many magistrates said they were concerned that those without lawyers faced being found guilty of crimes they did not commit.

One said: “Too many are pleading guilty because it is less expensive, rather than plead not guilty and receive high costs, when in fact one could argue they may have been found not guilty. In other words some would rather have a criminal record than high expenses, not realising later in life this could impact on them in relation to future employment or even travel abroad to, say, the USA or Australia/New Zealand.”

Another magistrate said: “The limited availability of legal aid has put many defendants at a disadvantage and I feel that some may have been found guilty of offences they did not commit or sentenced more severely than they would have been otherwise as they were unable to present their mitigation adequately.”

These latest revelations come in the wake of mounting anecdotal evidence of a rise in people being left to fend for themselves in criminal cases. Unlike the situation in civil and family law, where dramatic legal aid cuts in 2013 meant whole areas of law no longer qualified for free legal advice, in criminal law, the right to a legal aid lawyer has not changed significantly since 2010.

However, there are several reasons why it appears to be diminishing. Means testing for magistrates’ court cases was reintroduced in 2006, and for crown court cases in 2010.

The cutoff for qualifying for free legal advice in magistrates’ court has not kept pace with inflation, remaining unchanged since 2008. Only those with an income of less than £12,475 automatically get free legal advice. Couples with joint earnings up to £22,345 may also be eligible for some or all of their costs, depending on other factors, such as having children.

The latest government data for criminal legal aid in magistrates’ court shows that between April and June 2017 the number of orders granted for legal aid was down 10% on the same quarter last year. This has been driven by “summary offences”, where a judge decides without a jury. Legal aid grants in these cases are down 21%.

The MoJ has attributed this trend to falling crime rates, but the number of cases recorded in magistrates’ court fell by only 3%. The government says the proportion of legal aid applications granted in magistrates’ court has “changed very little over recent years”, remaining “at around 95%”. However, BuzzFeed News understands that many people are being advised not to apply because they are unlikely to qualify.

An MoJ spokesperson said: “The government’s 2012 reforms did not reduce access to legal aid in criminal cases before the courts in any way. In fact, last year we spent almost £900 million on criminal legal aid.

“Decisions on criminal legal aid are made by dedicated teams of expert Legal Aid Agency caseworkers. Any suggestions to the contrary – or that question whether the Legal Aid Agency is entirely independent of government – are utterly wrong.”

Penelope Gibbs, director of the charity Transform Justice, has been researching the impact of decades of cutbacks in criminal legal aid. In a report for the organisation last year she argued that there were several reasons why more people were representing themselves in criminal cases. For some it was because they were ineligible for legal aid, either due to their income or type of offence; for others it was due to a lack of awareness of their right to legal aid – and in a few cases, a basic lack of organisation.

She said: “Thousands of people are prosecuted for crimes and are not entitled to legal aid. Many cannot afford to use a lawyer. Evidence from our research suggests that anyone who doesn't have a lawyer is at a disadvantage, even if they plead guilty.”

Gibbs argues that complicated law and processes make it hard for those without help to understand whether they have a good defence. Her research suggests many will not be given evidence in advance as they should and will not know how to cross-examine properly.

“In the end, someone who appears without a lawyer is likely to get a tougher sentence,” she said. “And unlike in family and civil courts, there is no specialist help in criminal courts for people who do not have lawyers. It is a travesty of justice.

“I'm convinced that miscarriages of justice are happening every day in the criminal courts of England and Wales because people accused of crime do not have access to a lawyer.”

Gibbs points out that such an injustice would not happen in the US, where criminal defendants are all entitled to a lawyer in court.

In court three of Sheffield magistrates’ court, it is Shipman’s turn to appear. Walking slowly up to the dock, he looks up at the three magistrates who will decide his fate. His girlfriend, Natasha, tries to catch his eye and give a reassuring smile from the back of the room.

Beneath the magistrates’ dais is the prosecuting lawyer and to his right, in the seat closest to Shipman, there is an empty space where the defence should be.

A duty solicitor service operates in magistrates’ court, where those in the most serious cases get a free advocate on the day. But thanks to decades of slashed budgets, the “duty” can now help only in cases where there’s a high likelihood of imprisonment.

When Shipman was arrested he was allowed to see a duty solicitor at the police station, but he was advised that, along with being ineligible for legal aid, he would not qualify for the service in court.

He has decided to plead guilty though he has not yet seen any of the evidence for the prosecution. He holds his hands up to the possession charge but says if he had a lawyer he would have considered pleading not guilty to the driving charge, since he does not believe he was over the limit.

As the case begins, the court legal adviser, a trained lawyer whose chief role is to advise the magistrates on sentencing within the law, asks if Shipman has seen the case papers. He says quietly that he has not. A lawyer would likely have insisted on seeing these before a hearing.

The prosecution lawyer makes a punchy case with ease, saying that a blood test showed Shipman was three times over the drug driving limit for cannabis. The evidence is damning but it is the first Shipman has heard of it.

When the prosecution concludes, the court legal adviser tells Shipman: “This is your opportunity to address the magistrates, if you wish to.”

His response is brief and delivered quietly. He says: “Just that I regret my actions, really, and I apologise to the court. I’m taking steps to reduce cannabis use, which I’ve cut down considerably.”

His defence is weak. A lawyer might well have advised him to talk about “tackling” his cannabis use, rather than simply reducing it. They might also have pointed out his previous good conduct and the impact on his livelihood of a lengthy driving ban.

Outside court before the hearing, Shipman was nervous about the effect a driving ban would have on his job as an agency chef, which can take him around the country. A criminal record might also rule out work in some places.

In court, he is given a further nudge by the legal adviser to convince the magistrates of the impact a disqualification would have on him. She knows this is his opportunity to reduce any sentence – and would be seized on by any self-respecting lawyer.

His answer, delivered with flat resignation, is unpersuasive: “It will have some impact on myself, but that’s it.” After one final push, he elaborates, saying: “It will have some impact on my ability to work because I’m an agency chef and I have to travel to different jobs.” But he fails to give any detail or say anything about his good character or lack of previous convictions.

The whole thing is over in less than 10 minutes. He is disqualified from driving for 18 months and ordered to pay a fine of £220 for the driving offence, a further £50 fine for possession, a £30 victim surcharge, and £85 prosecution costs.

He is asked how much he could pay back a month and picks the figure of £60 – despite this being beyond the means he described to BuzzFeed News earlier. He later says he is worried about the amount and that he had no idea it was possible to pay significantly less than this per month.

An earlier hearing in the same court illustrates the potential difference a defence lawyer can make. A man is up on almost identical drugs charges. He too was caught driving under the influence of cannabis, though over the limit by a lesser amount. As well as being in possession of a smaller amount of cannabis, this defendant had cocaine in the car.

“Your worships,” his solicitor says, addressing them respectfully, before inviting them to consider the defendant’s good character and lack of previous convictions, and giving very specific guidance on a lenient sentence. The magistrates take note. Reading out his sentence, the lead magistrate says, “Taking into account your early guilty plea, the remorse you’ve shown, and your previous good character” the man will receive a 12-month ban and £335 in fines and fees.

The court legal adviser role has changed significantly in recent years. Their official job description is to advise magistrates and judges on the law, but as the number of people in court without lawyers rises, they are also having to advise defendants and nudge them into making their cases properly.

In Sheffield, a legal adviser who has been working with magistrates in these courts for two decades told BuzzFeed News the situation now risks serious miscarriages of justice.

“When I first started this job everybody got legal aid for every offence. It took a sudden dip when it had to be an imprisonable offence and it’s gradually tapered off. It’s just tailed off and tailed off.”

Describing one recent case, she said: “A guy pleaded guilty to driving whilst disqualified. Then it came to sentencing and I’m looking at the DVLA printout and he wasn’t actually disqualified. And when I raised with him, ‘Why have you pleaded guilty to this?’ He said, ‘Because the police told me I was.’ It was only because I had the DVLA printout that it transpired that he wasn’t.”

Mitigating circumstances are often forgotten without a lawyer to tease the information out of the defendant, leading to harsher sentencing. “Someone will plead guilty to common assault and not understand the defence they could give, like self-defence or duress,” the adviser said. “You’d never know that was a miscarriage of justice, because if someone doesn’t want to engage when it comes to sentencing you just wouldn’t know.”

Clamming up is another issue. “A lot of people will say ‘I don’t want to say anything.’ It’s difficult because you’re making a sudden judgment. Someone you see who’s in tears and struggling, you try and tease information out of them.”

She says a well-trained legal adviser offers some protection from miscarriages of justice. But not all are as diligent about this new facet of the job – and they can’t put words into a defendant’s mouth.

“I think the legal advisers and judges are a safeguard but I think the main difficulty is the majority of unrepresented people just say nothing,” she says. “A solicitor would spend time and tease it out of them, which you can’t do in court. You don’t get half the story, particularly from someone who doesn’t want to open up.”

Since legal aid decisions were taken away from court officials, she has seen more refusals on grounds of means and interests of justice (i.e., the seriousness of the case and its impact on the defendant’s life). “You’ll see possession of a bladed article and they’ll say ‘custody not likely’. Means and interests of justice get refused a lot more than they used to.”

She says it will often appear that a defendant has decided to go it alone, but it later transpires they simply cannot afford a lawyer. “You have people coming in and will say, ‘I’ve chosen not to be represented.’ And they’ll say, ‘It would be £600 to see a solicitor and although I’ve not passed the threshold for legal aid I’m not well off. OK, I earn more than £12,000 but that doesn’t mean I’ve got £600 up front to pay a solicitor.’”

Responding to the survey for BuzzFeed News, one magistrate said that typically the court’s legal advisers were too pushed to work with unrepresented defendants because the courts were “inefficient and unprofessional”.

They said: “Legal advisers don't have the time to give the help these defendants need. Justice is definitely NOT seen to be done. These defendants often make their case much worse and/or antagonise all court users.”

The other issue that no court legal adviser can help with is making defendants use the language that a lawyer might.

Andrew Dalrymple, an experienced defence solicitor in Sheffield, said: “The majority of defendants in magistrates’ court are being judged by people who’ve got lots and they’ve not got much. There’s still people being told off for calling the judge ‘love’ when they’re just trying to be emollient, or just told off for putting their hands in their pockets when they don’t know what to do with their hands.”

One prosecutor with more than a passing resemblance to Mr Toad is waiting for his case to start. BuzzFeed News asks him what it’s like going up against defendants without lawyers. “Easy!” he booms back, rubbing his hands together and laughing. “It makes life easier because you haven’t got people raising nitpicking legal points.”

Seeing the aghast expression of other lawyers and officials in the court, he backtracks and claims he was joking, adding: “You have to be fair, so you find yourself gently explaining things to them.”

Not all the prosecutors are so happy about the situation. Another lawyer from the Crown Prosecution Service says there is “definitely an increase” in the number of people coming into court without a lawyer and that she feels sorry for them navigating the system alone.

“Whilst we’re not supposed to be doing the defence work, you end up feeling you have to help them understand.

“A defendant doesn’t necessarily know what to say. They’ll not necessarily think that’s what’s important…. It’s not great for anybody.”

Though the cases in magistrates’ court are at the lower end of the spectrum, a conviction still results in a potentially life-changing criminal record, regardless of the severity of the punishment.

Lesser crimes do not necessarily translate to a lesser impact on a person’s life. BuzzFeed News came across a coach driver with a disabled son who stood to lose his licence for going 10mph over the speed limit. He had to present his case with no lawyer at all.

Another man with no lawyer, whose only defence for having offered a single joint of cannabis to a teenage girl was “I was just having a little bit of a laugh and having a little spliff”, ended up with fines and a 12-week nighttime curfew. He tried to explain that such a curfew would interfere with his ability to see his child, but his explanation was so incoherent that it appeared to have little effect.

It was only after sentencing – when it was too late – that the man realised how ineffectual his arguments had been. “Could you do anything less for that please?” he asked the judge, “You couldn’t give me a fine?” The judge responded bluntly, “No, it’s too serious.”

According to magistrates, the absence of a lawyer often has a stark impact on the outcome, despite the best efforts of the court. One commented in response to the survey for BuzzFeed News: “Almost all today's defendants would not have elected trial if they had had the benefit of legal advice. Five cases were abandoned as they were not prepared for the day. Public money wasted, and justice not really served.”

Another magistrate put it bluntly: “I cannot recall any cases this year where non-represented persons defended themselves effectively.” Similarly unequivocal, another said: “There is no doubt that litigants in person are significantly disadvantaged at all stages in the process. They can not possibly be expected to understand.”

There will always be a minority of people who decide against enlisting legal help out of stubbornness or mistrust of the system. BuzzFeed News has documented the phenomenon of so-called “Freemen”, who represent themselves in court because they consider man-made law to have no power over them.

But nobody who BuzzFeed News saw over several days of reporting in Sheffield magistrates’ court wanted to be there alone. They simply had no choice.

With white hair and a white beard, Mike Jones is visibly one of the most seasoned defence lawyers in the building. He is aghast at the way criminal legal aid has been chipped away through the decades he’s been working.

“There are a lot more unrepresented defendants going through the magistrates’ courts and a significant increase in the number in the crown courts. If you spoke to a crown court judge they would tell you they hardly ever saw an unrepresented defendant five years ago, but now they would tell you they see them quite frequently.”

Like others, he is concerned about the way the Legal Aid Agency is deciding whether a case should get funding. “There’s a perception that the Legal Aid Agency is enforcing the interests of justice test, otherwise known as the Widgery criteria, much more aggressively,” he said. “And so you’re having clients applying for legal aid who are being refused on interests of justice. We are having to appeal more of these decisions than ever before.

“At the first stage they’re refusing a lot more than they’ve ever done. We’ve had refusals of legal aid on domestic assaults. We’ve had refusals of legal aid on matters of burglary. They don’t have to justify it. They say the court legal adviser can assist the defendant. Well, I’m sorry but that’s not the same.”

Lawyers say the sliding scale of legal aid is putting people off too. Those on low incomes who don’t qualify for the full amount will still have to pay back significant sums to the state for a lawyer. Some choose to opt out of the legal aid process for representation throughout their case and instead pay privately for smaller amounts of time.

The duty solicitor system is supposed to offer protection for people with the most serious cases who find themselves in court without a lawyer. But the quality of the available advocate is not guaranteed – and is no replacement for having a lawyer who meets you in the days before a hearing to flesh out a case.

One magistrate said: “The issue of the quality of the ‘duty’ is also a problem; the range of ability is very marked – from excellent to barely competent. This can also affect the outcome of the court process.”

The duty solicitor often only manages to see a client minutes before a hearing and does not always have time to check whether everyone waiting to go into court has had the advice they’re entitled to. Diligent court ushers can paper over the cracks.

Tom Carden, 53, who had a duty solicitor at the last minute for his hearing on an assault charge in Sheffield magistrates’ court, told BuzzFeed News: “I said [to the usher] I was going to plead guilty and that I couldn’t get hold of a solicitor. The usher said, ‘You can’t do that without legal representation. Let me see what I can sort for you.’”

The rules say that a duty solicitor can also act for only one court appearance. This means even if a defendant manages to use one, if their case is adjourned they still have to face the remainder of their time in court alone.

One magistrate said: “There are many cases where, through no real fault of the defendant, the matter proceeds to a second hearing date and it often seems unfair that there is no access to a duty solicitor at that point. I often come away from a day in court feeling that the absence of legal aid, or access to a duty solicitor for one or more defendants, puts a spotlight on the inequality of the system for those without money.”

Among the most disadvantaged in court are those with learning difficulties or low levels of literacy or language skills, who struggle to put their point across well or follow the process.

One magistrate said: “Offenders with language, learning difficulties are the most likely to be unaware of what is going on – they might be capable of defending themselves, if they were given better understanding of what was going to happen before coming to court. If legal aid for such people is never to return, a simplification (in language) for almost all correspondence with the police and court would be beneficial. It is a waste of court time to have to do it there.”

Another said: “On at least two occasions recently I have sat in a trial that should never have come to court, because the defendant had not received advice to plead, which would have been a better outcome for them. One of these cases was of a Traveller with a very low level of literacy who really should have had his own help. It’s very hard to deliver justice in these circumstance and, as importantly, one gets the impression that the defendants leave court feeling more strongly than normal that justice has NOT been done.”

Two greying criminal defence solicitors are having a tea in the Sheffield court’s drab basement cafeteria. They say all the defence lawyers round here are old – the pay and hours are putting off new recruits as legal aid fees have been slashed again and again over the last decade. On top of this, prohibitive amounts of paperwork and fewer contracts mean it is an increasingly unpopular field.

Geoff Flemming, a criminal defence lawyer in Sheffield since 1984, says: “There are very few young people in the trade. Most of us are reaching the end. If you’ve got £50,000 of student debt you can’t do something for love any more. I think the job will become obsolete. I think the magistrates’ lawyer will go the way of the typewriter repair man.”

Flemming says the people who are losing out as legal aid gets cut will be those on lower-middle incomes. “If you were a school teacher and you got charged for assaulting some pupil who’s been asking for it for years, that’d be a problem. Always the people who suffer are the people who have a respectable but not particularly well-paid job. It’s the nurse, the school teacher, the librarian. That’s always the strata of society that gets hit by these things. A couple, both teachers, would struggle to get legal aid and if they lose their case they’re going to get wiped out.”

The paperwork for applying for legal aid used to be a 10-minute job, but lawyers say more than half an hour is now typical of the online form required by the Legal Aid Agency and that this makes taking on work even less viable than before. In the case of defendants who are self-employed or who do casual work, proving their low income can be so time-consuming that BuzzFeed News understands some lawyers now refuse to take them on for legal aid at all, knowing that the time spent applying would use up their whole fee.

Shaking and biting her lip to stop the sobs, a 28-year-old woman who looks half as old is standing in the dock at Sheffield magistrates’ court. Deep scars on her forearms are visible beneath rolled-up sleeves and her fragile mental health is evident. Too frightened to look up and barely able to whisper her name when asked it, she has no lawyer to make her case.

She has pleaded guilty to assaulting a police officer, though assault is a strong term for her offence.

A lawyer would give the court a chance to hear her side of the story; her brief testimony, such as it is, is barely audible. They might also have spared her some of the ordeal.

The offence happened in the early hours of the morning a few weeks earlier. When her boyfriend was arrested she became distressed, shouting at the police that he shouldn’t be taken away. She was drunk and frightened and screaming at a policewoman who tried to calm her down. In the fracas she spat at them several times.

The prosecutor concedes there was “no actual injury” although the spitting is being prosecuted as assault.

Her attempt at a defence is simply: “I really do suffer badly from anxiety and I wasn’t aware why my partner was arrested. I got very worked up and I don’t remember it. It’s not me normally – I just got worked up.

“I am really sorry,” she says, crying again.

Her sentence is not a harsh one for this category of crime, £160 in fines and fees, and the magistrate says: “We take into account your early guilty plea but this was an assault on a police constable and that cannot be tolerated.”

The woman’s case is one of several witnessed by BuzzFeed News where the defendant has mental health problems.

One man, recently divorced and suffering from severe depression, has been summoned to court for stealing two packs of lightbulbs. The only reason the shop got the police involved was because he didn’t have any ID on him at the time of the incident. He eventually sees the duty solicitor but is scared by having arrived at court without a lawyer of his own.

For those with serious mental health problems, a lawyer is a vital backstop. In one case in Sheffield magistrates’ court, a defendant with symptoms of psychosis, who is being supported by mental health services, is accused of breaching a restraining order by going to a fish and chip shop.

Shortly after his lawyer puts in a not guilty plea he starts weeping loudly and shouting “I’m guilty!” The harassed-looking solicitor manages to persuade the judge that the not guilty plea still stands.

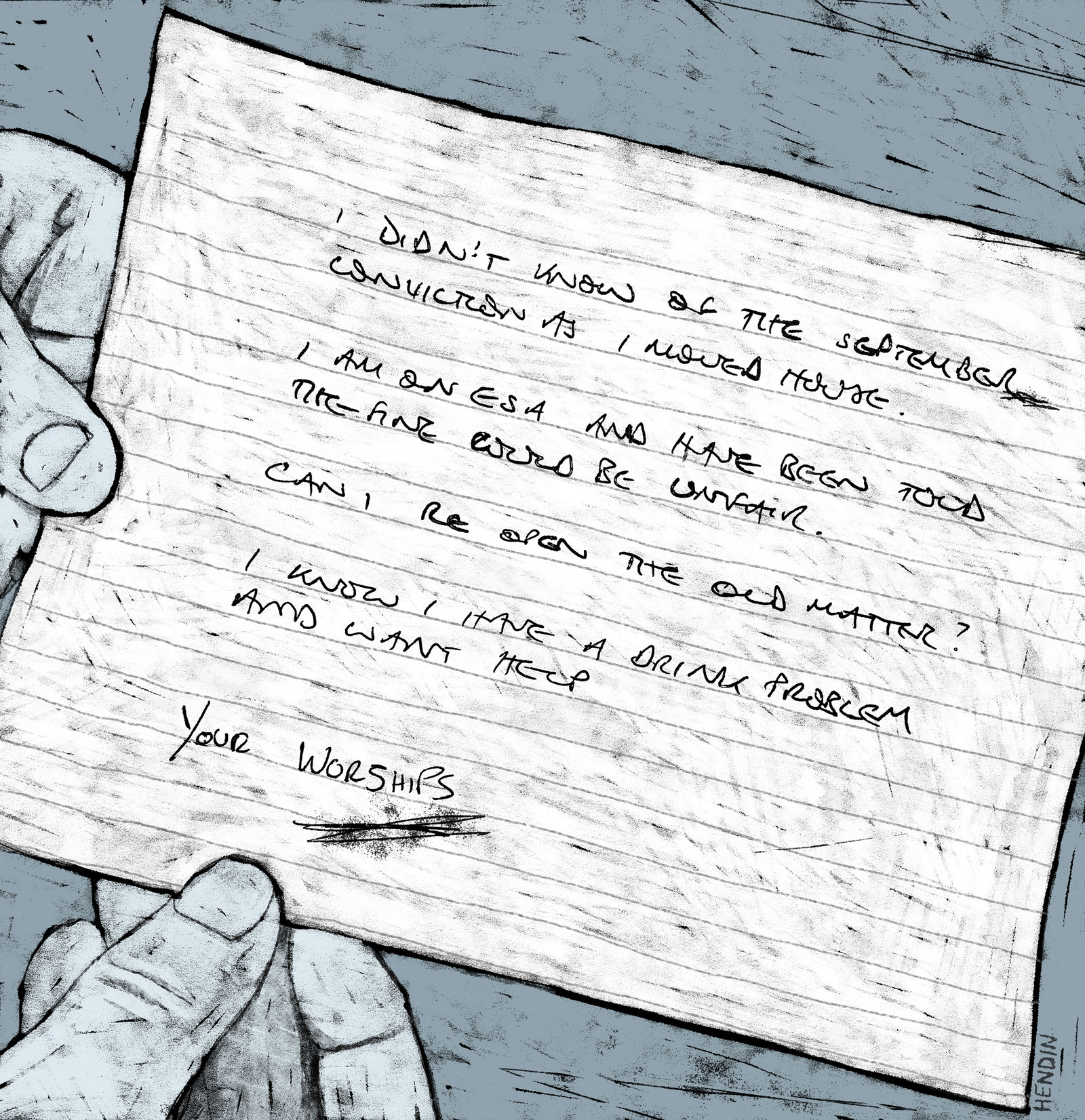

For most of those with mental health problems facing court alone, cases fall apart because of what’s not said. One woman BuzzFeed News interviews says she has been struggling with depression and anxiety and is an alcoholic. Knowing the impact her nerves may have, she clutches a piece of paper with some scrawled advice from a lawyer who once helped her boyfriend. The most important point is underlined at the bottom: to address the magistrates as “your worships”. The lawyer knew what she did not – that the correct use of deferential terms might help win favour.

She is pleading guilty to a charge of being drunk and disorderly after standing outside a police station and shouting at officers inside. “I did try and get a lawyer but because it’s drunk and disorderly I wasn’t able to. But I feel I need one. I’ve been having problems for the last few years and I’ve been suffering from depression and anxiety and I’m an alcoholic. I’ve got to stand up and say something, but nobody seems to help you. They just bring you to court and give you a fine.”

In an interview before her court appearance she described experiences that might explain her anger at the police – and could have been mitigating – but without a lawyer to coax these out of her, she clams up in the dock. She is given a fine but the judge does not refer her to any rehab for her drinking, despite her pleas.

“A lawyer could get me some help and make the court understand why I’m drinking and doing what I’m doing, because I self-harm and I need help,” she says. “I don’t need a bloody fine. I need help.”