People who have to represent themselves in court via videolink face “huge challenges” in getting fair hearings, according to new research.

The government has been rolling out video call hearings, sometimes known as virtual courts, across the country. Between 2016 and 2017 more than 137,000 cases were heard using a videolink, a 10% increase on the previous year.

But research by the charity Transform Justice, based on interviews and a survey of people across the legal world, has suggested the use of video seriously impacts on the chance of a fair hearing. The situation is particularly difficult for the rising number of defendants who cannot afford a lawyer to be in the courtroom for them.

Almost three-quarters of the lawyers, magistrates, and legal experts surveyed said people who had no lawyer were disadvantaged by appearing via video.

Folarin Oyebola has represented himself on a videolink without a lawyer seven times while trying to fight the fallout from his conviction for mortgage fraud from prison. He lost every time.

Oyebola told BuzzFeed News his worst experience was in the Court of Appeal in January 2016 when he was appealing a confiscation order of a property. He had to present his case via video from Pentonville prison, where he was serving his sentence.

“It was horrible,” he recalled. “[The judge] didn’t understand what I was saying at all. It was like speaking into a hollow chamber. I was shouting and it kept echoing back.”

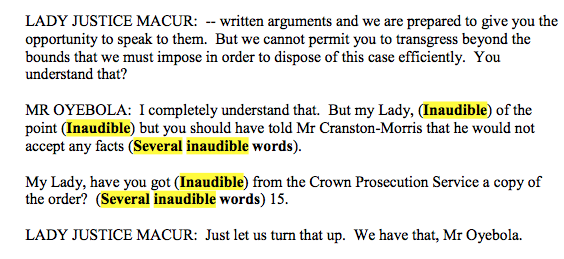

BuzzFeed News has seen a transcript of the hearing and there were 71 moments where what he said was inaudible to the transcriber. In nine of these, several words were missing.

The judge appeared to be struggling to hear and at one point Lady Justice Macur said "just let us turn that up". Before reading out the judgment, she asked for Oyebola’s sound to be turned off, saying: “I would like to say for the purpose of the record, there is a considerable amount of background noise which causes me to require that the volume is turned off so as to mute the sounds coming from Pentonville prison, please.”

Oyebola said: “She didn’t feel comfortable and that’s why she had to tell me to turn off the microphone so she could hear properly. If she’s telling me that, you can imagine then [what it’s like for] me presenting my case in such a forum. If [the sound was good enough] then they wouldn’t be turning off my microphone.”

He said the sound quality was bad for him too. "The Court of Appeal is such a big hall. People sitting in the court can hear themselves very well but when you’re listening on video there’s an echo."

He added: "In videolink there’s that delay which is not live and therefore you don’t want to interrupt the judge. It’s better when you’re in court and it’s live because you don’t have that delay and you can watch the judge’s reaction."

Oyebola said he believes fighting a case on video without a lawyer means judges “don’t take you seriously” and that the problems were not confined to audio quality. In another hearing via videolink, Oyebola recalled: “I was telling the judge about a document and they said, ‘Well, can you just tell me what’s in it?’ When you’re in court and can just give a judge a document, you are confident the judge is on the same page.”

A spokesperson for the judiciary said: “Judges do not comment outside court on cases, but they always decide cases on the evidence and the law and if something is not audible then judges or lawyers seek clarification at the time in court. Transcripts are not made live in court, they are made by playing back a recording and the quality of that recording depends on the state of the equipment and the quality and positions of the microphones. The word 'inaudible' in the transcript applies to the recording, not to the evidence.”

The expansion of video hearings is a key government modernisation policy with the stated aim of creating cheaper, more efficient justice. But an evaluation of the pilot of the first police station virtual courts, published in 2010, showed them to be more expensive than traditional courts. Defendants appearing on video were also less likely to take up (non means-tested) legal advice, and more likely to get a prison sentence.

The latest Transform Justice survey, which was completed by more than 200 lawyers, magistrates, and courts staff, found that 58% felt it made it harder for defendants to understand what was going on in their court hearing and to participate.

Penelope Gibbs, director of Transform Justice, said: “It’s difficult enough for someone to defend themselves without a lawyer. Put that person on video and you double those difficulties. In a court an unrepresented defendant can have a face to face meeting with the legal adviser before their case is called, and in the court hearing itself they can use body language as well as words to communicate.

“If someone is trying to represent themselves over video, they often cannot hear well what is happening in court and they certainly can't feel the atmosphere of the court. Understanding a process designed for lawyers while disconnected from the court itself faces an unrepresented defendant with huge challenges.”

The study also found defendants can be disadvantaged in sentencing by not being in the same room. One prosecutor told the researcher: “Psychologically, it is easier to do something negative to someone when they are not physically present. When I prosecute a bail matter, I prefer the defendant to be on the [video] link. When I defended, I always sought to have the defendant present in court, so the judge or magistrates would have to refuse bail ‘to their face’.”

Andrew Langdon QC, chair of the bar, said: “Government plans to invest in virtual technology for court hearings hold the promise of savings and greater efficiency but we must recognise that they also pose a real threat to the quality of justice.

“Barristers who appear regularly in courts or tribunals will tell you that many strictly procedural hearings could take place via conference calls or video link without any detriment to the quality of justice. But they will also tell you that the quality of justice can suffer and that outcomes can be different when we lose face-to-face contact between judges, witnesses, victims, clients and their lawyers. This is especially so when dealing with people who have mental health problems, intellectual disabilities or who are otherwise vulnerable.”

Poor technology is also a major problem, according to the research. A survey of judges published earlier this year found that more than a third of district judges and 16% of circuit judges were concerned by a reduction in face-to-face hearings. More than half said the IT quality was poor.

One police officer described their experience with a videolink as “so temperamental it would have been quicker to transport [the prisoner] from the prison to the court”. They said using video held everything up, explaining: “There was a long delay to get the system functional. There was a delay between video and audio so the defendant was struggling to follow what was happening.”

A legal adviser said: “Often the audio quality is poor – there have been times when part way through a case the defendant has indicated he can't hear what is happening. People often don't speak up if they can't hear/see what is going on. In the court we sometimes can't hear all of what is being said by the defendant.”

Commenting on the technical problems faced by many courts, Langdon said: “As this research study suggests, many practitioners also have concerns about the quality of the technology currently being used and how well defendants and other participants in a hearing understand what is happening. Virtual hearings carry with them some very real and obvious risks.

“Before pressing ahead, it is vital that the Ministry of Justice undertakes comprehensive research to determine the impact of virtual hearings on outcomes and quality. We otherwise risk making profound changes to our system of justice without having a clear idea as to the consequences. It is currently unclear if parliament will have the opportunity to scrutinise these proposals before they are taken forward, but given what is at stake, we suggest that research and meaningful consultation as to the wider consequences are paramount.”

Virtual justice also particularly disadvantages disabled defendants, those with learning difficulties and those who don’t speak English as a first language, according to the study. While allowances are supposed to be made in court for those with disabilities, 70% of those surveyed said it was difficult to recognise whether someone who was on video had a disability.

Jonathan Marks, justice spokesperson for the Liberal Democrats, said: “There is clearly a space for ‘virtual justice’ and the benefits should not be brushed aside; however, justice must never be undermined or denied as a result. We absolutely have to get this right and this report shows that at the moment the government are failing.

"The Liberal Democrats will be highlighting this report to the Secretary of State for Justice and urging his department to respond to the troubling findings it has unearthed”

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Justice said: “We are investing more than £1 billion to transform and modernise our court system.

“We know video hearings reduces court time, improves public safety and saves money for the tax-payer. Video link technology is also being used to make the court process easier for thousands of vulnerable victims and witnesses.”