Keir Starmer has given a lot of stump speeches so far in this Labour leadership campaign but never before in a venue like this. Outside, the rain is lashing down in Blackburn, Lancashire; inside, the swirly silver chandeliers are sparkling as Starmer stands in front of Roman columns topped with garlands of artificial flowers. Across the room, in his eyesight, sits an oversize zebra-print chair that stretches to the ceiling. This is a glitzy Asian wedding venue; the night before, he was in an arts centre in Edinburgh — the evening before that, West Ham Town Hall.

The speech remains broadly the same though: the devastating general election result, the need to win back voters across the whole of the UK (not just those in northern heartlands), the pledge to unite the party and be an effective opposition against that “liar” Boris Johnson, all that Labour has achieved in government, and — finally — the need to stop “wallowing in our loss”. Starmer paces in front of the audience, his voice raised: “We can mope around for the next four years, taking lumps out of each other. We can do that — we’re quite good at that! — or we can pick ourselves up, and we say, ‘We can change this if we pull together.’”

Most of the 80-strong crowd get to their feet and applaud. “He’s much more interesting in real life, isn’t he?” one woman whispers. This is a key challenge for Starmer: How does he convince Labour members at large — and, ultimately, the country — that he is more than the dull, meticulous man in a suit they’ve seen at the despatch box?

There are bigger challenges too: his knighthood and five-year stint as director of public prosecutions (DPP), not to mention his central London constituency, mean he struggles to escape the “establishment” tag. One recent focus group described him as “quite boring” and “corporate”, somebody at home “in a big room with very high-powered people, not somebody for the people”.

His three years at the side of Jeremy Corbyn, the man widely blamed for Labour’s worst election defeat since 1935, angers many voters who believe he did not do enough to stop the party hurtling out of control. Starmer’s role as shadow Brexit secretary only compounds that; allies say he eventually succeeded in bringing together a deeply fractured party, but critics say Labour’s ultimately convoluted stance only managed to alienate both Leavers and Remainers. He is also the only man in the contest, despite conceding that Labour is long overdue in electing a woman as leader (just not right now).

Starmer, who became a member of Parliament in 2015 after a long and high-profile legal career, will not fit neatly into a political box. He is dismissed as a Blairite centrist by the left and a radical Marxist by the right. He praises both Corbyn and Tony Blair as excellent party leaders. He is not surrounded by a clique; he has friends in the Conservative party and is rarely seen in the Commons bars like most ambitious politicians. In fact, it’s been noted how strange it is for a potential party leader to have not amassed any real enemies in Parliament. Starmer is, arguably, too bland for that, and not political enough.

And yet his whole life has revolved around politics and social justice, shaped by the long nights he spent in hospital as a child with his severely ill mother, the human rights cases he took on as a young barrister fighting against the state and big corporations — and the difficulties now faced by his wife and sister, who work in an overburdened NHS and social care system.

Now he wants to lead Labour when the party is at its lowest ebb, when it needs to gain 124 more seats to win a majority of just one at the next election (“We’ve got a mountain to climb,” he often says, solemnly). BuzzFeed News spoke to school friends, former colleagues, and fellow parliamentarians to try to unearth the real Keir Starmer: a man rooted in politics who is not a natural politician.

Starmer’s team denies he has long been preparing to succeed Corbyn as leader. But he has certainly put in the groundwork; he endlessly toured seats around the country last year, visiting MPs and giving speeches at local party dinners, despite his heavy workload as shadow Brexit secretary. He travelled to 44 constituencies during the five-week election campaign.

For his allies, this moment has been a long time coming: When former Labour leader Ed Miliband lost the 2015 general election, Starmer was urged to stand and replace him — despite becoming an MP just weeks earlier. He backed Andy Burnham in that summer’s contest; when Corbyn won by a landslide, Starmer accepted a job as shadow home office minister. He then resigned in the attempted mass coup against Corbyn in 2016 — saying he backed challenger Owen Smith “100%” — but later that year returned to the front bench as shadow Brexit secretary, and has since remained a loyal ally of Corbyn’s, outwardly at least.

Charlie Falconer, the Labour peer and barrister who was lord chancellor under Blair, has known Starmer for many years. He told BuzzFeed News: “I think he’s been appalled by the awfulness of the current leadership — not so much on policy but on the nastiness and the way they did things.”

Asked why Starmer hadn’t spoken out while he was on the front bench, Falconer said: "He has on anti-Semitism. Anyhow, a lawyer can’t say 'fuck, my client — the Labour leadership — is awful,' but that is how it’s been for the last three years.”

Starmer lavished praise on Corbyn in his speech to members in Blackburn. “There is the most intense media pressure on all politicians, and it’s intense in particular on the leader of the Labour party,” he said. “And we’ve just seen Jeremy Corbyn vilified not just in this election campaign but in all of the years he was leader.”

“They’ll go for you too!” one man shouted from his seat. Starmer said he, like many others, had been told by voters that they couldn’t back Corbyn — but he insisted their views had been tainted by inaccurate media portrayals.

“It’s not just Jeremy; it was Ed Miliband too. It’s wrong, it does affect things, and we do need to do something about it,” he told the audience. “If you lose elections, there’s nothing you can do about that.”

He did not elaborate on what exactly he would do in government to restrain the media in this way. But underlining this apparent call for further state intervention, Starmer also pointed to the “falsehoods put out by the Conservative party in this election, sometimes amplified by the press”, saying: “There’s an urgent need to look at how that all operates.”

Just six days later, Starmer launched a rallying cry for press freedom after a number of political journalists were turned away from a briefing in Downing Street. After the incident sparked outrage on social media, Starmer released a public statement, calling on the cabinet secretary to investigate Number 10 and declaring: “Banning sections of the media from attending important briefings about important matters of government is damaging to democracy.”

Starmer’s critics within the party told us these contrasting views of the press reflected his tendency to “flip-flop” and say different things depending on the audience he was speaking to at the time. “He’s always triangulating rather than putting out a coherent message,” one said. “That’s because he has no real politics.”

The reality is that hedging his bets and playing to both the left and the right of the party could be his best chance of winning this contest. He points to his campaign team as proof he is serious about uniting the warring factions. Jenny Chapman, a former MP who was vice-chair of Blairite pressure group Progress, is his campaign chair; Simon Fletcher, ex–chief of staff to Corbyn, is strategic campaign adviser; Kat Fletcher, who also worked on Corbyn’s 2015 leadership campaign, is director of field; and Morgan McSweeney, who ran Liz Kendall’s doomed leadership bid, is campaign manager.

Behind the scenes, some Labour MPs bemoan Starmer’s “safe” campaign — just as Johnson relied on a drama-free campaign during the election to get him over the line — and hope he will show a firmer sense of his political vision, and more personality, if he becomes leader on April 4.

Starmer’s world view has been shaped by his family, particularly the fortitude shown by his mother, who was disabled for most of his life. He was born in 1962, the second of four children, to nurse Josephine (Jo) and toolmaker Rodney (Rod) Starmer. She had to give up work due to Still’s disease, a rare autoimmune disorder that causes the body to attack its own tissues.

Starmer has many fond memories of his childhood in Oxted, east Surrey: His mother would make him jam sandwiches after school, and they would listen to Jim Reeves’ Welcome to My World together. But he also remembers spending long, horrendous nights with her in the local hospital’s high-dependency unit as she received treatment for a disease that was causing her so much pain.

She took steroids that allowed her to stay mobile for many years, defying the doctors who told her in her twenties she would never walk again. In her later years, however, she had her leg amputated and was unable to properly sleep, talk, and eat. Starmer has said he’s been heavily inspired by her courage and determination.

He was the only one of the four Starmer children to pass the 11-plus exam, and he went to the all-boys Reigate Grammar School, which became a fee-paying school a few years after he joined. There he shared violin lessons with Norman Cook, aka Fatboy Slim, and sought out friends who were also interested in politics.

Andrew Cooper, the Conservative peer and co-founder of polling firm Populus, caught the bus to school with him. "His public persona, I think, comes across as quite sort of dour and a bit wooden and a bit self-important, and that is not him at all,” he told BuzzFeed News. “He was very charismatic and humorous. And he was very popular. In the queue for the bus, he would be the person leading the conversation and telling the jokes.”

The pair were both in the East Surrey Young Socialists, which Starmer has since described as being “very radical but not very big”. Cooper said: "We were, slightly weirdly, young socialists in a very, very safe Tory seat. We're talking about a time when the Labour party was Bennite. Whereas usually the young socialist group was sort of further to the extreme, our group was very mainstream.”

Supporters of Starmer’s left-wing rival, Rebecca Long-Bailey, accuse him of talking up these socialist roots in a bid to win over the membership, saying his politics have shifted right since he was a teenager. But Starmer insists he has not changed. He told the Camden New Journal, his local newspaper, last month: “I am a socialist. For me, what I’m driven by in this is the very deep inequalities that we’ve now got across the country of every sort: Income, wealth, health, influence, it’s deeply ingrained.” He said that did not mean an endless debate about nationalising services, but “a very forward-looking radicalism”.

While Starmer’s childhood home was a “bit like a building site, never quite finished”, it was a “very joyful and very intense house [where] everyone had to make their points of view known”, according to a school friend. Starmer’s parents were animal lovers who rescued donkeys and Great Danes in their spare time (“Whenever one of us left home, they were replaced with a donkey,” Starmer has said).

His father, Rod, who was well known in the local community, worked in a factory every day from 8am to 5pm before coming home for his tea and going out to work again. His engineering skills allowed him to create a modified wheelchair for his wife later in life so they could still enjoy walks in the Lake District. After he left school, Starmer took a gap year and spent several months working in the factory with him.

His mother, Jo, died in 2015, just two weeks before Starmer was first elected as a Labour MP. His father died in December 2018, just as Starmer was dealing with a series of key Brexit votes. Rod spoke of his pride for his son in a local newsletter several years earlier, describing how Starmer was awarded his knighthood at Buckingham Palace: “We were the proudest parents there; Keir was treated like a Lord and we were looked after like a Lord’s Mum and Dad!!”

Now, Starmer is dealing with yet more personal tragedy at another key moment in his political career. His team announced on Sunday that his mother-in-law died after a fall two weeks earlier. The accident has been a huge shock for his wife, Victoria Alexander, and their two children, aged 11 and 9. Starmer has cancelled a number of campaign events.

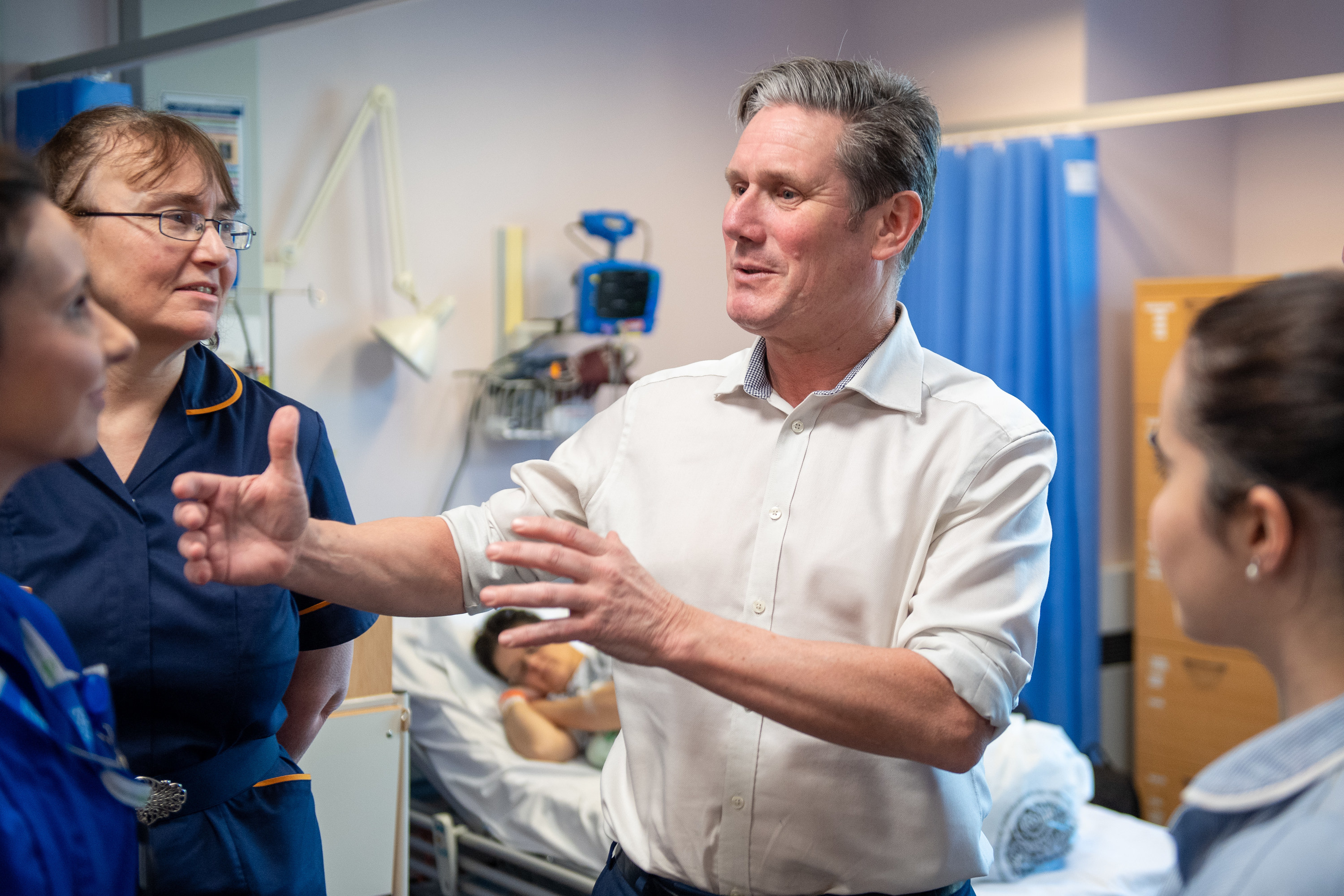

A few days after the accident happened in January, Starmer told an audience in Stratford, east London, that he was in awe of the NHS staff treating her in intensive care. “I’ve seen surgeons and nurses with incredible dedication and professionalism,” he said. “Our NHS is the best in the world. It deserves much better than what it’s getting now.”

This is an issue close to his heart: His wife, who used to be a solicitor, now works in the local NHS hospital in occupational health and is “overburdened in her team with too much to do”. “It’s a reflection on the legal profession that they thought she had taken a step down,” he added.

Starmer also feels strongly about the country’s creaking social care system, not least because his own sister is a social care worker. “It needs a fundamental review. It needs to be professionalised, and workers need better respect,” he said.

The NHS has been at the heart of Starmer’s campaign, not least when his team announced that the first baby born in the health service, Aneira Thomas, was backing him. Last year, he told of his mother’s pride in the NHS: “In that high-dependency unit, near death, where they weren’t sure they had the facilities for her, she held my arm and said: ‘You won’t let your dad go private, will you?’”

Starmer’s current image as an apparently corporate establishment figure is at odds with the life he led in his early twenties. Fresh out of studying law at Leeds University and postgraduate studies at Oxford, Starmer was a man filled with radical ideals. He juggled his early legal career with coediting the monthly magazine Socialist Alternatives, which strongly criticised the direction of the Labour party under “neo-Keynesian” Neil Kinnock.

Starmer wrote several articles himself, including one about the dispute between Rupert Murdoch and print workers in Wapping and the policing methods at the picket line. “This leads to the question of the role the police should play, if any, in civil society,” he wrote. “Who are they protecting and from what?”

He also interviewed left-wing icon Tony Benn at his home, who insisted that he sit in a chair that once belonged to Labour’s first parliamentary leader, Keir Hardie, because Starmer was named after him. Starmer did struggle to shift copies of the magazine, though. His school friend Paul Vickers, who later became his flatmate, once told how “we sat surrounded by boxes of thousands and thousands of Socialist Alternatives”.

Vickers, a journalist at Private Eye magazine, died in 2017. At his funeral, Starmer reunited with Cooper and other old friends who reminisced about their time in a “hovel” of a flat in Archway, north London. Starmer was just out of university when Vickers asked him to move in. He soon discovered that various windows were broken, there was a big hole in the kitchen floor (which grew in size over the years), and it was located above a sauna and massage parlour. Still, it was just across from the tube station and the rent was low.

Cooper lived in the four-bed flat before Starmer did. He said it was “really incredibly cheap” but “really grungy”, and their landlord was eventually sent to prison for living off the earnings of prostitutes. “Keir and Paul lived there for several years, and then I believe it was condemned as unfit for human habitation by Haringey Council,” Cooper said. “But it was incredibly convenient, right opposite the tube.”

Vickers described Starmer, in an interview recorded in 2009, as a “very driven and focused” person who was constantly at his desk poring over his books and files. “He was very keen on [reggae singer] Desmond Dekker: His favourite record was Israelites. We’d have to listen to it dozens of times a week,” he said.

One day, Vickers came back from work to find two burglars carrying their television and video recorder down the stairs. “I ran upstairs thinking I was going to find an empty, ransacked house — and there was Keir sitting at his desk working,” he said. “He was so obsessed with his books, so buried in his texts, that he didn’t notice two burglars walking round the house, helping themselves to our stuff.”

This was the mid-1980s, when Margaret Thatcher reigned supreme. Starmer’s politics were described as “hard left”, and any decision in the flat had to be made collectively. Within a few years, he was working as a barrister with Doughty Street Chambers, a group well known for its work on human rights and civil liberties whose notables now include Amal Clooney.

Falconer, then a commercial barrister, said Starmer was a "very intense, committed, slightly isolated figure" when they first met. "He’s not a particularly clubbable figure; he is a man alone,” he said. “He is the real deal — every time you would speak to Keir, he would be engaged in a particular cause. He was completely motivated in all he did in the law by politics.”

That work ethic comes up repeatedly in interviews with those who know Starmer well. Georgia Gould, Labour leader of Camden council where Starmer is now the local MP, told BuzzFeed News: “I say to him, ‘It's alright. I can do this one. You can have a day off’. I don't know when he sleeps. He hates being late — he'll say to me, ‘Georgia, we're gonna be late. We can't be late.’”

Some MPs think Starmer’s dedication to his work will make him a dangerous opponent for laid-back Johnson, while others dismiss him as lacking in personality and charm. (His team points out that his complicated, detail-heavy Brexit brief has made it difficult for him to show much personality.) He gets mixed reviews from Tory MPs.

One cabinet minister told us: “He is by miles the best candidate. A Trot, yes, but a professional, and he’ll be good in Parliament.” Another minister described him as the “Michael Howard of the Labour party — a good stopgap”. A new Tory MP in northern England said Starmer wouldn’t connect with his constituents: “He’s almost embarrassed of everything he has achieved — own it, man!” Another Tory MP said bluntly: “Ed Miliband with a knighthood.”

This is how Starmer sums up his legal career in his leadership launch video: “Standing up for the powerless and against the powerful.” The four-minute film intersperses grainy footage of protests against Margaret Thatcher with moody shots of former mineworkers and images of MPs and media bosses outside court.

Here is a man who stood up for the ordinary people, it says: defending the print workers in Wapping, the dockers in Dover, the poll tax protesters, the miners, the environmental activists — and, later, prosecuting those at the heart of the establishment.

As a defence barrister, Starmer took on a raft of anti-establishment causes, including pro bono work trying to get rid of the death penalty in Caribbean countries, defending MI5 whistleblower David Shayler, and acting for two environmental activists who were sued by McDonald’s. The latter case was made into a documentary film, McLibel, by Franny Armstrong and Ken Loach, an old friend of Corbyn’s.

Away from the high-profile cases, Starmer also defended Paul Staines, now better known as political blogger Guido Fawkes, back in 1989 when Staines worked with the organisers of acid house parties. Starmer, who represented the National Council for Civil Liberties, argued that Thames Valley Police had acted unlawfully by setting up roadblocks and confiscating sound equipment to prevent a rave from taking place. It was “an incredible abuse of police powers”, he said.

Falconer said Starmer has always been “utterly committed to the causes of the left”: “He could have made all the money he wanted. He never did. Politics always dictated the work he did.”

Starmer was celebrated as a “legal crusader” in liberal newspapers, and speculation began to grow that he was the inspiration behind Mark Darcy, the dashing human rights lawyer in the novel Bridget Jones’s Diary, played by Colin Firth in the 2001 film. BuzzFeed News contacted author Helen Fielding to establish the truth behind the claims, but she remained enigmatic on the subject.

Starmer became a Queen’s Counsel and joint head of Doughty Street Chambers in 2002. He also served as human rights adviser to the Northern Ireland Policing Board. Heather Williams, then the deputy head of chambers, remembered him juggling his work and football commitments at weekends.

“He would be at chambers 6am Sunday morning, then played football at 10:30am, then he’d come back afterwards,” she told the BBC. Football remains Starmer’s passion; he’s an Arsenal season ticket holder and plays five-a-side in Kentish Town once a week alongside the son of singer Edwyn Collins, among others.

Starmer met his wife when she was working for a firm, preparing case files for him before he went into court. “The bundles of documents in front of me had to be 100% accurate,” Starmer said at an event last year. “I phoned up to check and said: ‘This schedule? Is it any good? Is it absolutely accurate?’ She quite indignantly, quite rightly, said: ‘Absolutely.’ She says she then put the phone down and said: ‘Who the fuck does he think he is?’” They married in 2007.

“I don’t think anyone really expected someone who dedicated his career to defending workers, trade unions, and activists to become director of public prosecutions,” campaigner and peer Doreen Lawrence said in Starmer’s campaign video. She praised Starmer as being “instrumental” in getting justice for her teenage son Stephen, who was killed in 1993; two men were eventually convicted of his murder in 2012.

Starmer’s appointment as head of the Crown Prosecution Service in 2008 confounded many people: the human rights activist turned chief prosecutor for the state. This was “classic poacher-turned-gamekeeper territory”, one journalist said to him when he took on the role. Starmer defended the move as “protecting the vulnerable and giving people access to courts where they wouldn't otherwise have access to courts”.

His scale of ambition was clear, and the move did not go down well with Conservative commentators, who described him as a “bleeding heart liberal”. His five-year stint at the CPS, where he was simply known as “the Director”, included some controversial moments — from his clarification of the law on assisted suicide to the “Twitter joke trial” that led to protests from comedians over the right to free speech.

Starmer faced fury in 2010 when he refused to prosecute a police officer involved in the killing of newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson, who died after being pushed to the ground during the G20 protests the year before. Commentator George Monbiot said at the time: “This is a moment in which the pomp and majesty of the law falls away to reveal a squalid little stitch-up.” Starmer reversed his decision in 2011 following an inquest into Tomlinson’s death.

At one of Starmer’s recent campaign events in Stratford, one Labour member raised concerns about his record in the CPS; she was concerned he had not prosecuted the police over the shooting of Jean Charles De Menezes. He denied being involved: “A decision was taken not to prosecute in that case two years before I was appointed as director of public prosecutions, so there’s a false story going round.” Speaking to BuzzFeed News afterwards, the young woman said she still had doubts about Starmer’s ability to “proactively combat institutional racism within the police” and would probably vote for Long-Bailey.

As DPP, Starmer also flexed his muscles against the Westminster elite by prosecuting several parliamentarians over their expense claims, followed by then–cabinet minister Chris Huhne and his wife for perverting the course of justice. He went to war with journalists by paving the way for prosecutions against Rebekah Brooks and others at News International for phone hacking. Brooks was acquitted but features prominently in his campaign video. Trevor Kavanagh, political columnist at the Sun, has described his actions against journalists as “the longest, costliest and perhaps most spiteful criminal persecution in history”.

Starmer was awarded a knighthood for services to law and criminal justice in 2014 (although he will insist that you don’t call him “Sir”: “I’ve never liked titles”). Peter Tatchell, a human rights campaigner and longtime acquaintance of Starmer, remembered him as always being “very open to representation from outside his own circle” as DPP.

“I was involved in helping to defend two Balochistan activists who the government of Pakistan was trying to frame on terrorism charges,” he said. “When I approached Keir about the case he immediately said ‘Come in and see me. Let's talk about it.’ He was a very high-profile, busy man at the time but he took the time, you know, which I think is a measure of his character and integrity.”

Tatchell said Starmer would make a “fine Labour leader” but said he hoped he would take on some of the “very thoughtful, intelligent proposals” made by Clive Lewis, the left-wing Labour MP who dropped out of the leadership contest in the early stages.

“I think the Keir you see today is pretty much the Keir of 30 years ago,” Tatchell added. “He's got a very sharp mind and is very articulate. I think it would be a great asset if he can work on a sense of humour as well. … Yeah, it's a bit hidden.”

This is a common, and often exasperated, observation from people who know Starmer well and want him to win. One close ally described him as a “bit shy” and someone who feels uncomfortable being open about his life outside work. This only bolsters the idea of him as a businesslike figure with little personality; Starmer is apparently well aware he needs to work on this side of himself.

A live podcast recorded last year with comedian Matt Forde is a rare public example of Starmer in relaxed mode (“If you want to get an idea of what Keir’s really like behind the scenes, listen to that,” a friend of Starmer’s told us.)

Starmer told the audience how he was impersonated by a serial fraudster during his time at the CPS. Paul Bint, who had masqueraded as multiple QCs over the years, began hooking up with women via lonely hearts columns by telling them he was in fact Keir Starmer. He was eventually arrested and prosecuted in 2009.

“He took long taxi rides in my name and tried to buy a house and a piece of art in my name,” Starmer said. Laughing, he explained how one of Bint’s victims was asked in court why she hadn’t been confused that he didn’t actually look like Starmer. “I had my suspicions, but everyone can have a bad day,” she said.

One Labour insider who has worked closely with Starmer said he was “quite intense, someone who takes his work very, very seriously. … I also think there is a human side to him which doesn't always come out”. They added: “Corbyn didn't win by being a massive personality. He won by chiming with what the membership wanted — this contest will be won by Labour members thinking, ‘Who’s the best person to beat Johnson?’”

Starmer had always had half an eye on getting into politics and made the leap when the safe Labour seat of Holborn and St Pancras was vacated by veteran MP Frank Dobson in 2015 (insiders point out that Starmer had been showing his face at local community events long before then). Friends said his move into Westminster politics was in no small part driven by the level of budget cuts he encountered as head of the CPS.

Georgia Gould said she didn’t back him as Labour’s parliamentary candidate at first. “I was like, is he local? Is he a community MP?’” she said. “And I could not be more wrong about him. His dedication to supporting people locally, to supporting the council and being there for us has just been amazing. ... We really rely on him, you know, when things get difficult now.”

Starmer’s long legal career and scrupulous attention to detail made him the right fit for the shadow Brexit role, for which he went line by line through complex draft legislation and used arcane parliamentary procedures to embarrass the government and force them to release key documents.

But it’s clear that Labour’s long-winded handling of Brexit — culminating in a policy that satisfied neither true Remainers nor Leavers — played a big part in the brutal general election result, and Starmer has been blamed for that. The final plan was to secure a new Brexit deal with the EU and “within six months” put that deal to a public vote alongside the option to remain.

One Labour staffer said it had been a huge mistake to pursue the second referendum so vigorously when so many of Labour’s traditional supporters just wanted to see the back of the whole thing. But another party source said it was “fantasy” to think that Labour could have had a strong Remain or Leave position: “It just couldn't be done. Labour was in an impossible position. The people who have a problem with our Brexit position want to distract from the fact that Jeremy Corbyn was a disastrous leader of the Labour party.”

Cooper said: “The demographics of Brexit just are more difficult for the Labour party than they are for the Tory party, and there's no getting around it. I assume that left to his own devices, Keir would have had a more explicit second referendum position. And I think if they had had that position, the result would have been less bad for them. But that does come at a significant price.”

Falconer said that Starmer’s open-door approach over Brexit eventually united most of the parliamentary party, which was “pretty impressive”. He said: “The way he did it was treading the minefield and getting a policy that ultimately he believed in over a long period of time, rather than briefing the media, flouncing out, complaining bitterly about it. Instead he steadily worked to persuade the leadership team without falling out with or complaining about them.”

In recent weeks, Starmer has been trying to move the conversation on, saying that while Johnson’s future trade deal with the EU should of course be scrutinised, the era of Remain versus Leave is over. Critics say this is wishful thinking on his part and that Starmer will always be remembered as a Remain pin-up.

At the meeting in Blackburn, Starmer conceded that Tory messaging during the general election campaign had simply been far more effective: “‘Get Brexit done’ was just left there, and we weren’t knocking it down. We didn’t have an equivalent,” he said. “It was the same in 2015, people said, ‘We’re not voting for you; you don’t have any money left.’

“We haven’t had message discipline and message clarity for some time now. The Tories have done it in just a few words — ‘Take back control’, ‘Get Brexit done’, ‘Oven ready’. We need direct, clear messaging.”

But Starmer also knows there are some things in life that are bigger than Brexit. Gould said she remembered one particular week last April when there were several crucial Brexit votes in the Commons and a young person was stabbed to death in the street in Starmer’s Camden constituency.

“He was somebody who was well known and well loved, and I texted Keir to let him know,” she said. “And within five minutes he was on the phone, saying, ‘What can I do?’ The next day, I was going to visit the bereaved family. And I again texted him and said, ‘I really don't expect you to be able to get down from Parliament’ — but he just got on the tube, came down, and spent over an hour sitting with the family, listening to them. Then he went back to Parliament with nobody the wiser.”

Starmer has faced questions over whether he’s the right person to win back Labour voters in northern England. Does he really have anything in common with them? In Blackburn, Starmer confronted this head-on: “We need a very clear plan to make sure we can win those seats back. But if that’s all we do, we’re going to lose the next general election.

“The next PM of this country needs to be able to speak to the whole of England, the whole of Scotland, the whole of Wales, the whole of Northern Ireland.”

If you draw a line between London and Bristol and looked south, he said, there are more than 120 seats up for grabs. Labour has just a handful. “We’ve lost four general elections in a row now,” he said. “If we don’t win in 2024, then a whole generation will have grown up without Labour — that is tragic.”