At the beginning of the second semester of her freshman year at Washington State University in January 2014, Rose was playing drinking games with her new floormates. After she lost, she told BuzzFeed News, she peeled off with a classmate she had “kind of a crush on” and they had sex in her room.

A few months later, she was expelled for sexual assault.

Rose’s situation is unique because she is a woman being accused by a man of a sexual assault on campus. “My firm has done more than 70 of these cases and I’ve talked to dozens more people,” Justin Dillon, an attorney who specializes in defending college students accused of sexual assault, told BuzzFeed News. “I have never seen a case like this.”

Title IX — the federal gender equality law under which most college sexual assault cases are considered — was created to protect women from discrimination. University Title IX offices infrequently face cases of alleged female-on-male sexual assault, which experts said means there are few, if any, precedents for how to investigate a case like Rose’s. Title IX was not set up to deal with a reverse in gender.

It’s not that these cases don’t occur – men account for around 17% of sexual victimizations of students, and survey data collected by the Association of American Universities shows that many of these men were assaulted by women. Men are much less likely to report sexual assaults to legal or university authorities than women, though they will report them on anonymous surveys.

Part of this is due to societal pressure to act “tough,” said the Health and Human Rights Law Project’s Lara Stemple, who analyzed the AAU data. But it also has to do with how men think of what rape and sexual assault means. “Many men consider rape a women’s issue,” Stemple said, “even if they know what happened to them was nonconsensual.”

All these factors make staying unbiased in cases like Rose’s “really difficult,” Colby Bruno, an attorney with the Victim Rights Law Center, which has dealt with hundreds of college sexual assault cases, told BuzzFeed News.

But, “if the victim truly believed it to be nonconsensual [sex],” Bruno said, “then expelling her was the right decision.”

Rose, who asked to be identified by her middle name, is now 21. She was at WSU on a scholarship and was on track to graduate this May as prelaw with criminal justice and political science majors. She was recently laid off from a minimum-wage retail job due to cutbacks.

Rose applied to WSU’s neighboring school, the University of Idaho — which would accept the third-party scholarship she is on — but said she was rejected because their public safety board said her disciplinary record was “a risk.” (Cezar Mesquita, the director of admissions at Idaho, told BuzzFeed News the admissions board must be able to “assess risks to our overall community” when looking at a student’s disciplinary background, though he could not comment specifically on Rose’s case.)

Rose insists she was falsely accused. She believes her accuser complained to the college’s Title IX office — the Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO) — “because his friends were making fun of him for sleeping with me,” because, she said, “I am short and overweight.” She filed a counterclaim with the same office and the result of the full investigation was her expulsion.

BuzzFeed News obtained a Student Conduct File collected by the WSU Office of Student Standards and Accountability (OSSA). It includes a “Final Memorandum” that spells out the logic behind their decision.

The OEO and the OSSA interviewed the male student, three of his friends who were witnesses, and Rose. Rose provided transcripts of text messages from that night and records of building entry card swipes to back up her timeline. The male student did not respond to BuzzFeed News' multiple requests for comment.

The five students gave conflicting accounts of the evening, but their statements recorded in the Final Memorandum generally concurred on this narrative:

During the drinking games in a friend’s room, the male student drank nearly a fifth of Fireball whiskey and some vodka and beer — the witnesses said Rose drank “just a bit,” while Rose said she drank up to 15 cups of vodka-spiked Hawaiian Punch. He and Rose went to her room. At one point, he left to ask his friends for a condom. He and Rose performed oral sex on each other and attempted vaginal sex. The male student told the OEO that after he ejaculated he felt “really uncomfortable” and “kept trying to leave,” but Rose asked him to wait.

His friends said about seven people were gathered outside Rose’s door listening to them. They spoke to him through the door while both he and Rose were undressed. One of the students said they did this was because they all thought the male student “did not want to do this.” At one point, he asked Rose to get his whiskey, and she briefly left the room while she did.

Eventually the student told Rose he had to “go find his friends.” He went to the room of one of the student witnesses, referred to as “Student C” in the memorandum.

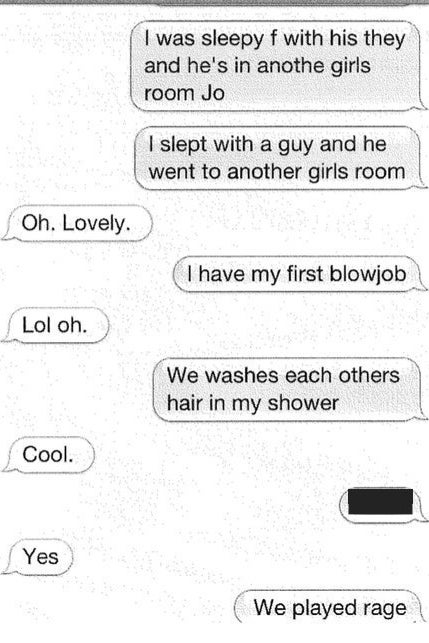

“I slept with a guy and he went to another girl’s room,” Rose told her friend in screenshots of misspelled text messages from that night. Rose went to Student C’s room and asked for him — he hid in the closet until Student C guided Rose away. Student C said she told Rose, “You could get in trouble for this, this could be considered rape.” Rose said Student C helped put her to bed.

While the male student was still hiding in the closet, Rose Facebook-messaged him, saying, “I miss you.”

In the days afterward, floormates teased and “joked” with the male student about sleeping with Rose, students told the OEO, often within Rose’s earshot. Some wrote, “Pray for [male student], [male student] was taken advantage of,” on the whiteboards outside their doors, the witnesses added. Eventually, a resident adviser caught wind.

A policy mandated by Title IX requires most university employees who are aware of alleged sexual misconduct to report it to administrators.

The student who accused Rose met with WSU’s Title IX coordinator, Kimberly Anderson, who told BuzzFeed News the first meeting with any student who may have been subjected to sexual misconduct is always about available resources and whether they want to file a complaint.

The male student gave his account and was offered another room to sleep in “if he felt unsafe” — it’s unclear whether he accepted. That evening, Rose was told by the hall director for her dorm that she had to move out immediately; the WSU Sexual Assault Policy recommends this “to support and protect the complainant."

She was not told why she was being moved out until three days later, when she was given a no-contact order with the male student and the investigation began.

In Rose’s first meeting with the investigators, she filed a sexual assault countercomplaint against the male student.

“I felt kind of taken advantage of because of how drunk I was,” Rose said, but added that the countercomplaint was more to “prove a point” than to have him investigated. “I just wrote that night off as I drank too much and hung out with the wrong people,” Rose said. “But if he wants to say it happened when it didn’t happen, I’m gonna say it when it didn’t happen.”

A student accused of sexual assault filing a counter sexual assault claim in the school or on a federal level is relatively common, though they are usually filed by men accused of sexual assault and are often dismissed. Anderson said that WSU takes these countercomplaints seriously. When one is filed, the school “re-reviews all the information from both perspectives,” giving both parties “equal consideration,” Anderson said.

“Who was most in control in the situation? Was one party engaging in isolating behavior? Who was less intoxicated?” are the main questions investigated, Anderson said. It often comes down to small actions and text messages or photos. “A witness testimony would probably have less value than an audio transcript or than a written record,” Anderson said.

The OEO determined Rose was “more likely than not” less intoxicated than the male student, based on the accounts of the male students’ friends. They said Rose was walking and speaking normally, while the male student was not. Rose also said she had a clear memory of the night, while the male student said he did not.

In nearly incomprehensible text messages, Rose told a friend that she threw up, that the male student’s friends “wanted her drunk,” that she gave "her first blowjob.”

But the timestamps of her texts vary — by about an hour — from the timeline given verbally by the male student and his friends. So the OEO dismissed the texts as evidence, saying that though “the messages support [Rose]’s assertion that she was intoxicated … it is not clear how the timing of the text messages corresponds to the timing of the events of that evening.”

Anderson said they also take into consideration whether the witnesses are friends with the complainant or respondent.

“We determine if it is possible they’ve colluded and set a story, and what their motive would be,” said Anderson. In the interviews, all of the students called themselves friends of the male student and said they did not know Rose very well. Rose said she gave the OEO the name of a witness who could confirm the timeline corresponding to the texts, but that to her knowledge the OEO never reached out to her. The witness, a residential technology assistant who lived on Rose’s floor and asked to remain unnamed, told BuzzFeed News that she knew Rose, but was never contacted by the OEO regarding the case.

The investigation lasted from the beginning of the second semester to the end of the school year. Because of this, Rose was kicked off her study abroad trip to England at the last minute and was forced to tell her parents why.

She worked at a café on campus that the male student frequented. Due to the no-contact order, the OEO was at first going to ban her from the dorm and the surrounding area, but after she explained that she needed to work to support herself, they changed their minds, according to emails from the school in the student conduct file. When the male student came to the café, Rose said, she had to ask a co-worker to serve him, or she would go to the back while he was present.

In May, the male student called a member of the OEO and asked them to drop the investigation, saying it was “too much” for him, according to notes included in the student conduct file. In July, he asked again to no longer be involved in the case and asked that the OEO make sure Rose never contacted him again. The investigation continued. Anderson said this is common practice, because the “respondent,” in this case Rose, “deserves some sort of closure.”

Anderson, in a statement to BuzzFeed News sent Wednesday, said the university “takes every complaint of sexual assault seriously.”

In general, she said, “in many cases of sexual assault, one or both parties have been drinking. WSU regulations are clear that use of alcohol or drugs is not a defense to sexual assault. This is true regardless of whether the aggressor is male or female and whether the victim/survivor is male or female.”

Anderson added that publishing information about a an alleged sexual assault “without the victim’s informed consent has the potential to re-traumatize the victim and is irresponsible, regardless of whether the victim is male or female.”

On Aug. 29, 2014, Rose received a letter telling her she had been found guilty of sexual misconduct, among other related charges, and that she was to be expelled.

The Final Memorandum detailing the reasoning behind Rose’s expulsion said the OEO found “insufficient information to determine the amount of alcohol consumed by Rose” and, a few sentences later, stated that the male student was “much more intoxicated” than Rose.

“[Rose] knew, or should have known of [the male student]’s level of intoxication and his inability to understand the nature or consequences of his actions,” the memorandum reads. This — and the allegation that Rose “attempted to isolate” the male student by not opening the door to her room fully when the male student’s friends were outside the door — were the two reasons the OEO gave for finding Rose guilty.

Rose appealed her expulsion twice to no avail. In April 2015, Rose filed a complaint with the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, which enforces the Title IX gender equality law. That September, the Department of Education opened up a second Title IX investigation into WSU — that and a first, unrelated investigation are ongoing.

Rose hired a lawyer with money from her savings to help her with the complaint. She chose not to take individual legal action against the school, she said, because she doesn’t want her name associated with the case online.