The Stanford Prison Experiment is arguably one of the most famous experiments in modern psychology and has been used as a demonstration of how people rapidly conform to their roles in extraordinary circumstances and perform acts that would be branded as "evil" in average contexts.

The experiment has become part of the fabric of modern psychology and has been taught routinely to first-year psychology students around the world, making an appearance in the great majority of social psychology textbooks.

However, its legitimacy is now being openly debated by a panel of international psychology experts including professor Philip Zimbardo, the researcher from Stanford University who designed and conducted the experiment.

So, what was the Stanford Prison Experiment?

The experiment was part of a trend in modern psychology to understand the emergence of violent and immoral human behaviour in different contexts in the wake of World War II and the Holocaust.

The experiment took place in the summer of 1971 using 24 male college student volunteers.

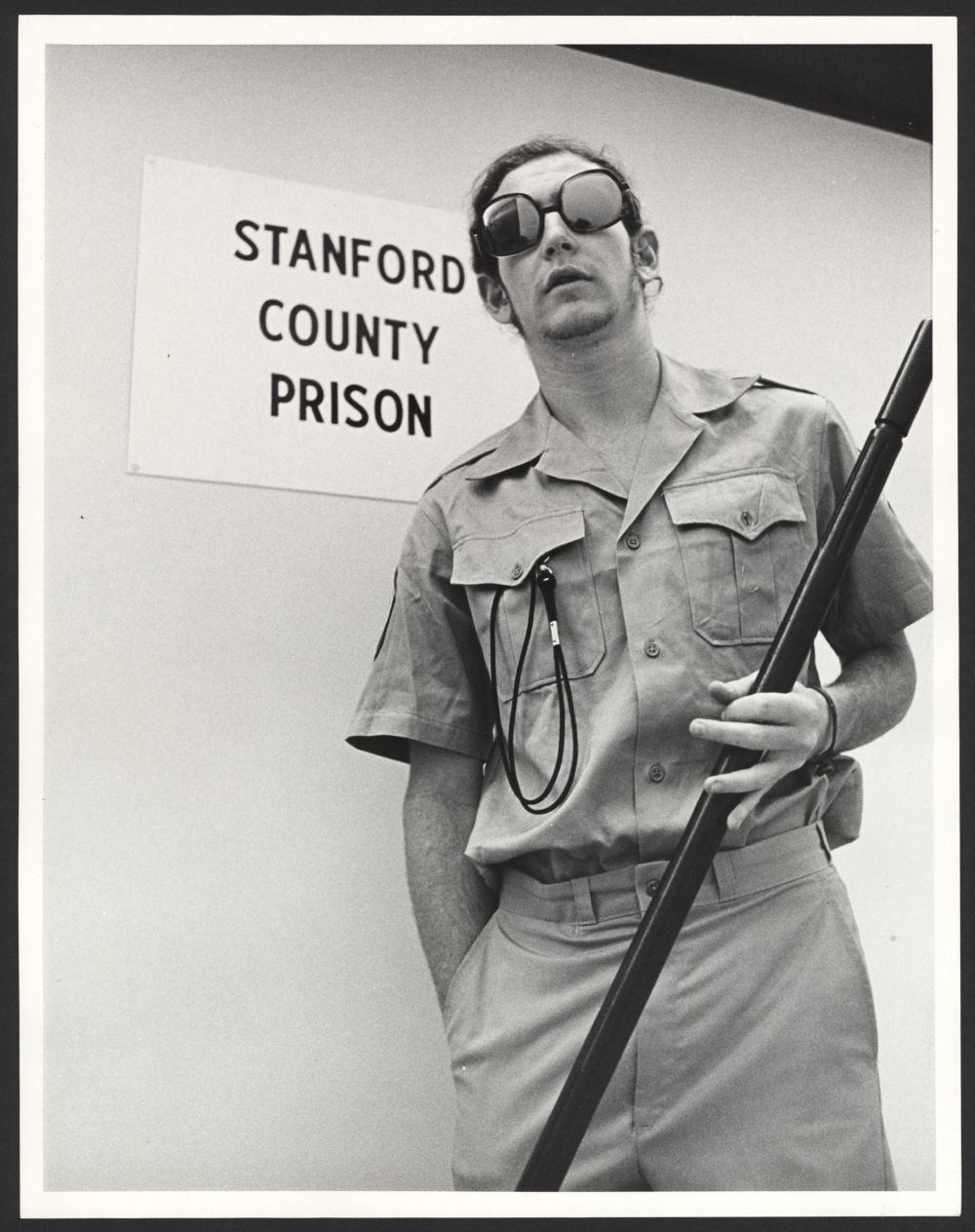

"Stanford County Prison" was created by boarding up and building cells in a section of the basement in the psychology department of Stanford University.

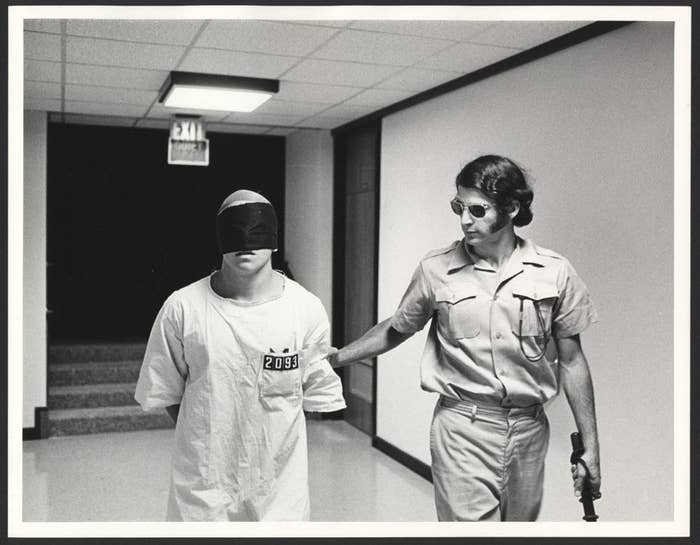

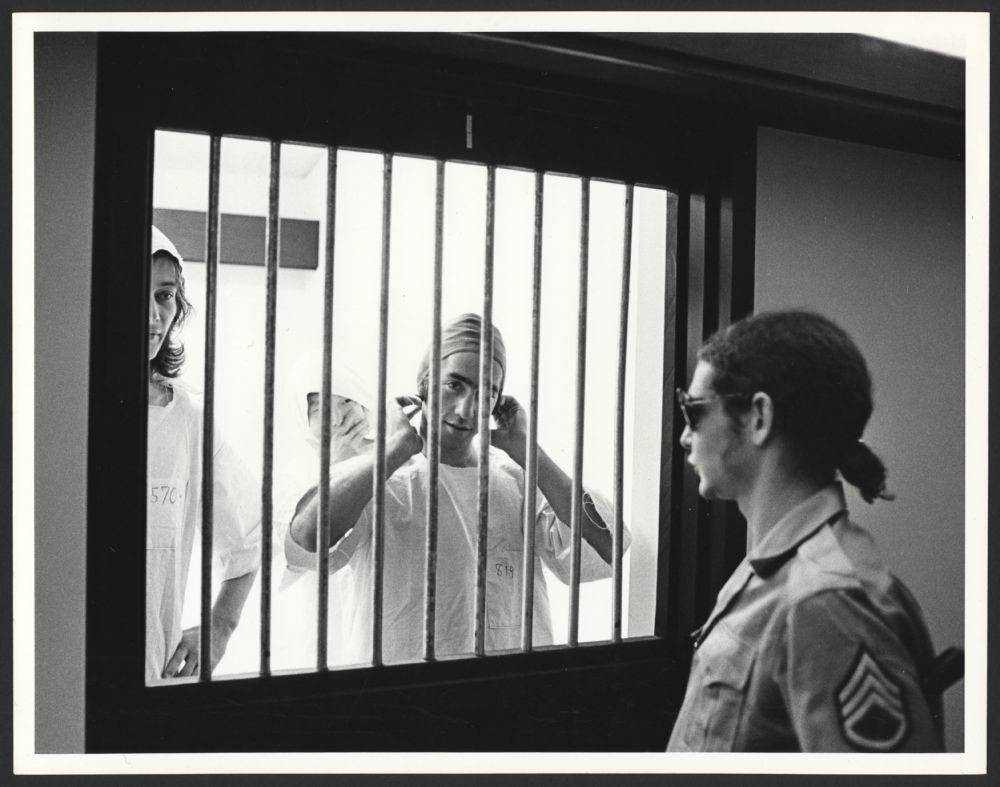

The participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups — guards or prisoners.

The prisoners were referred to by ID numbers rather than their names by the guards and fellow prisoners.

Zimbardo and his co-authors wrote a paper on the study, which began: "What happens when you put good people in an evil place? Does humanity win over evil, or does evil triumph? These are some of the questions we posed in this dramatic simulation of prison life".

The study began by "arresting" the prisoners and taking them from their homes in a police car. The prisoners were then searched, stripped naked and deloused with a spray.

Over the course of six days at the Stanford County Prison psychological and physical abuse was committed by the guards against the prisoners.

The study was intended to span a fortnight but was cut off early by legal complaints and the objections of a PhD student who was brought in to interview the participants.

The guards inflicted punishments such as menial tasks, exercising (jumping jacks and push-ups), solitary confinement, sleep deprivation and cleaning toilets with their bare hands.

One of the prisoners (#8612), Douglas Korpi, a 22-year-old Berkeley graduate, began to exhibit uncontrollable crying and rage 36 hours into the experiment, described by Zimbardo as "acute emotional disturbance".

Korpi told other prisoners "you can't leave, you can't quit" and he was removed early from the prison experiment due to his psychological distress.

Another prisoner (#819) was exhibiting psychological distress and continuous crying. Zimbardo recounts his release in his official report of the study:

"I suggested we leave, but he refused. Through his tears, he said he could not leave because the others had labelled him a bad prisoner. Even though he was feeling sick, he wanted to go back and prove he was not a bad prisoner.

At that point I said, 'Listen, you are not #819. You are [his name], and my name is Dr Zimbardo. I am a psychologist, not a prison superintendent, and this is not a real prison. This is just an experiment, and those are students, not prisoners, just like you. Let's go.'

He stopped crying suddenly, looked up at me like a small child awakened from a nightmare, and replied, 'Okay, let's go'."

The guards, who all wore opaque aviators (inspired by the movie Cool Hand Luke) were allegedly given no specific training on how to be guards in the official accounts of the study.

One guard, who was renowned for taking his role particularly seriously and acting with cruelty, was dubbed "John Wayne" by the prisoners.

Zimbardo reflected:

"Where had our 'John Wayne' learned to become such a guard? How could he and others move so readily into that role?

How could intelligent, mentally healthy, 'ordinary' men become perpetrators of evil so quickly? These were questions we were forced to ask."

The Stanford Prison Experiment has since been used in psychology as a demonstration of how humans can behave aggressively and abuse power and exhibit "evil" within certain authority contexts.

But now the experiment and the legitimacy of its results are being called into question.

In a consensus statement released this week, professors Craig Haney and Zimbardo from the Stanford Prison Experiment, as well as professors Alex Haslam and Stephen Reicher who conducted the BBC Prison Study, have called for a constructive debate on the findings and legacy of the experiment.

The BBC Prison Study was an experiment undertaken by Haslam and Reicher and broadcast in 2002.

The study was similar to the Stanford Prison Experiment and took place over nine days with five guards and 10 prisoners.

However, there was a profound difference from the results of Zimbardo's experiment in the power balance between the prisoners and guards.

In the BBC study it was found that the prisoners banded together and acted against the prison guards, challenging their authority and driving some distressed guards to leave the experiment.

Haslam and Reicher concluded: "People do not conform blindly to roles; they only internalise roles when they identify with the groups that create them."

The results of the BBC study, as well as decades of social psychology research, appear to contradict evidence from the Stanford Prison Experiment that it is context alone that leads people to abuse power or act sadistically.

The controversy begins with some perceived flaws in Zimbardo's experimental design.

Firstly, the digitisation of the footage and audio recordings from the Stanford Prison Experiment archive contradicted Zimbardo's claim that the prison guard's brutal treatment of the prisoners was a "natural" consequence of their assigned role.

In 2016, social science researcher Thibault Le Texier published Histoire d'un Mensonge (Story of a Lie), a book investigating inconsistencies in Zimbardo's original reports.

New evidence outlined in Le Texier's book suggested Zimbardo and the experimenters had, in fact, encouraged particular behaviours from the guards.

One audio recording of a meeting with an assigned prison guard involves Zimbardo's prison warden and researcher David Jaffe telling the guard that they "really want to get you active and involved because the guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a tough guard".

"You have to try and get it in you ... you have to be firm and you have to be in the action and that sort of thing," said Jaffe. "It's really important for the workings of the experiment."

Audio recordings such as these, as well as the transcript of the orientation of the Stanford County Prison guards, suggest that the participants were coached to act in a certain way, rather than exhibiting a natural abuse of powers.

Zimbardo himself told the guards in an orientation session:

"You can create in the prisoners feelings of boredom, a sense of fear to some degree, you can create a notion of arbitrariness that their life is totally controlled by us, by the system, you, me …

They can do nothing, say nothing, that we don't permit…"

Zimbardo has denied that these sort of statements could have such extreme implications for the way the guards behaved in Stanford County Prison.

In an interview with Vox's Brian Resnick, Zimbardo stated:

"The point is telling a guard to be tough does not mean telling a guard to be mean, to be cruel, to be sadistic, which many of the guards became of their own volition playing the role of what they thought was a prison guard. So I reject your assumption entirely."

Haslam, who has been studying the dynamics of social interactions such as these for decades and has formed theories that contradict Zimbardo's, told BuzzFeed News that the discovery of these recordings was like the "Rosetta Stone" for him and research partner Reicher.

Haslam's theory is that extraordinary accounts of extreme cruelty and dehumanisation that have occurred throughout history, such as the Holocaust and the Rwandan Genocide of 1994, rest upon nuances of leadership.

"Part of his [Zimbardo's] theoretical analysis is that if you put people in a toxic context, they will become toxic essentially on their own and that's really not what happens."

Haslam states that the recordings and transcripts are a "really important part of the study and it makes what happened in the Stanford Prison Experiment more relevant to us and more interesting to us in many ways".

Haslam stresses that in order to persuade people to act aggressively towards an out-group, they must be convinced that they have a common link and common grounds for motivation to act in that manner.

Haslam notes that in Jaffe's orientation session as prison warden, he used the term "we" approximately 50 times — a factor that contributes to the guards perceiving themselves as a united force against a common enemy.

In a 2007 paper Dr Thomas Carnahan and Dr Sam McFarland also put forward the idea that the results of the Stanford Prison Experiment were misleading because Zimbardo advertised for volunteers in the newspaper.

Carnahan and McFarland note that the sort of personalities who put their names forward for such an experiment from newspaper advertisements were rated highly on "Machiavellianism, narcissism and social dominance, and lower on empathy and altruism".

The treatment of the prisoners, as well as the legitimacy of their reactions, has also come into question.

According to an investigation by author Ben Blum, who wrote a piece deconstructing the Stanford Prison Experiment titled The Lifespan Of A Lie, Korpi (Prisoner #8612) denies that his psychological breakdown was legitimate.

Korpi told Blum: "Anybody who is a clinician would know that I was faking ... If you listen to the tape, it's not subtle. I'm not that good at acting."

Korpi and fellow prisoner Richard Yacco reported that they were simply shocked that the experimenters would not let them leave Stanford County Prison when requested to exit the study.

However, Zimbardo denies this claim in the interview with Resnick, saying he believes Korpi made his statement in retrospect because he is "ashamed of having broken down".

So, what do other studies say?

In 1979, professor Sydney Lovibond from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) conducted a study that looked at the effects of three different types of "prison" regimes, including one based on a normal medium-security prison, and two that allowed prisoners to participate and exhibit individuality.

The study observed some of the same behaviours of exertion of authority by the guards over the prisoners, including the following interaction:

Officer: Get your head in.

Prisoner: Why?

Officer: Because I'm an officer and you're a prisoner and I'm telling you — that's why!

Prisoner: It's an open window and I've got a right to look out.

Officer: In a real prison there wouldn't be an open window, and as such you wouldn't have the right to look out. Now get your head in!

Prisoner: Well, it isn't a real prison is it, and I'll look out when I want to — mate!

Officer: You're on report.

Prisoner: Big deal.

Officer (putting his face close up to the prisoner's): You've got four more days in here sonny, four more days remember?

However, the most important difference between Lovibond's conclusion and Zimbardo's is that the UNSW study found it was the "social organisation" of a prison regime rather than the characteristics of the individuals themselves that most influenced the behaviour exhibited.

Haslam also concluded in another paper that in classic conformity studies such as Zimbardo's or Stanley Milgram's obedience and electronic shock experiment (in which participants were found to willingly submit their peers to dangerous electric shocks when told to by researchers), there is always a significant amount of resistance to the demands.

In the Milgram experiment, participants actually exhibited three types of explicit resistance to the researchers' demands.

Haslam notes that the guard who was told to act "tough" by Jaffe in the audio recording was being instructed to do so because he wasn't submitting sufficiently to acting as the guards were expected to.

He believes that this aspect of significant resistance to authority regimes has been ignored by the conformity narrative.

So, why does any of this really matter?

The implications of Zimbardo's study – that people will conform to roles and abuse authority without question – have far-reaching political consequences.

Haslam believes that Zimbardo's conclusions need to be inspected because they suggest people will always fall in line with authority, despite moral objections.

"It's also I think very politically problematic to suggest that if you put people in bad situations, they'll do bad things, because it takes away any agency and it also takes away responsibility."

Haslam hopes that an open debate with Zimbardo and Haney will lead to a more nuanced discussion about personal responsibilities in the face of authoritarian regimes or bodies of power.

"The point is, in history tyranny has always been overthrown because ultimately people push back against it and say, 'This is not right'".

* BuzzFeed News has sought comment from Professor Philip Zimbardo.