Mary Moss had to make a decision when her child came out as a transgender boy. "My choice was a live son or a dead daughter,” Moss said. “I don't see what choice I have. And I am certainly not going to be my child's first bully.

“So I said, 'We are going to do this.'"

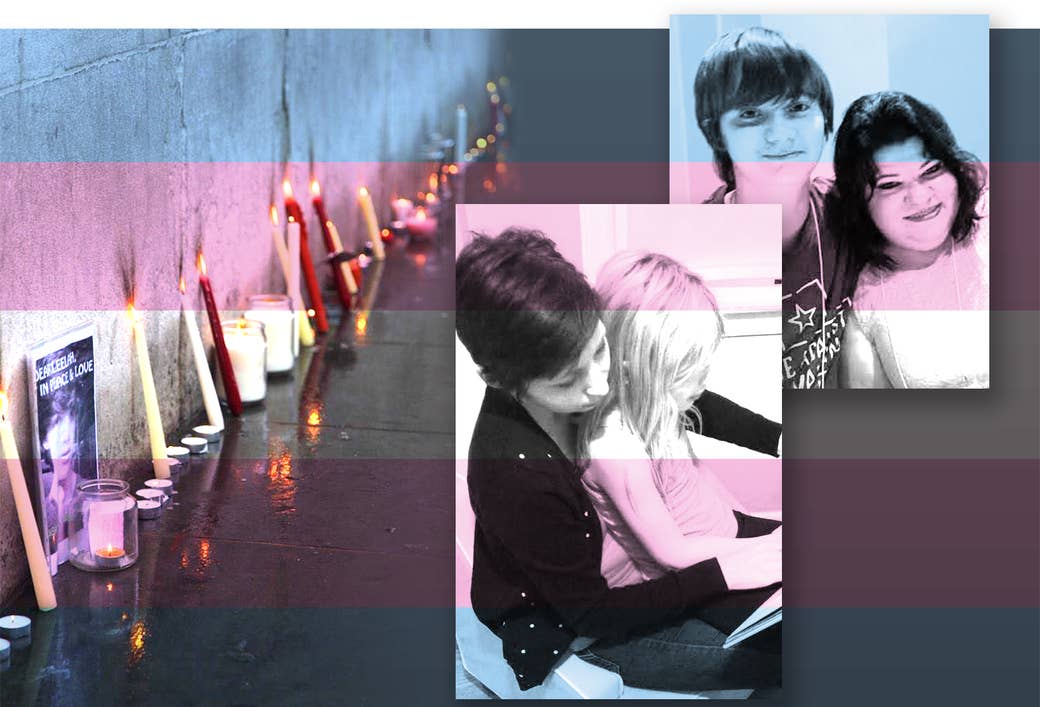

Many parents choose differently. Seventeen-year-old Leelah Alcorn killed herself in December, leaving behind a suicide note that described how her parents censored her gender expression, cut her off from friends, and pulled her out of school. They sent her to conversion therapy, Alcorn wrote, where Christian counselors said "that I was selfish and wrong and should look to God for help."

Far from an anomaly, Alcorn’s tragic death is part of a well-documented pattern: Research shows transgender children rejected by their families are far more likely to commit suicide. Even after their daughter died, Carla and Doug Alcorn rejected her gender identity, telling reporters that they loved their “son.”

But Moss and parents like her are part of a far different story unfolding. Faced with transgender children coming out at increasingly younger ages, families are showing acceptance and support. In interviews with BuzzFeed News, parents said even deeply religious, politically conservative families can love and respect their transgender children, without compromising faith or ideology. The results, they say, are kids living happy lives.

These parents — including an ordained Catholic deacon in Florida and a former Southern Baptist in Missouri — offered advice to other parents in their shoes. One such piece of advice came from Debi Jackson, the former Southern Baptist, who still identifies as a conservative guided by her Christian faith.

"I would just tell them to look at the statistics,” she said bluntly.

Forty-one percent of transgender or gender nonconforming people attempt suicide, compared to only 1.6% of the general population, according a 2011 survey by the National Center for Transgender Equality.

LGBT youth from "highly rejecting" households are more than eight times more likely to attempt suicide than those in supportive households.

Rejection at home sharply exacerbates that risk. LGBT youth from "highly rejecting" households are more than eight times more likely to attempt suicide than those in supportive households, according to a 2009 study by researchers at San Francisco State University's Family Acceptance Project. Those researchers also found seemingly less-hostile behaviors, such as silence or discouraging discussion about a teen's LGBT identity, were experienced by teens as dangerous forms of rejection.

"The real tragedy," said Caitlin Ryan, a Ph.D. who has researched LGBT youth behavior at the Family Acceptance Project for more than 14 years, "is that parents with rejecting behaviors think they are helping their child, helping them fit in, helping them learn morally correct behaviors. Their motivation is to help that child, and we are helping them understand those behaviors are related to serious health risks.”

Figuring out what it means to help a transgender child is a struggle for even the most supportive parents. "People say, 'What if your child changes her mind?', or, 'You're not a good mom and complicit in this,'" said Moss, who is raising her teenage boy in upstate New York. But in the end, she said, “The suicide rate is so high, and it goes down lower and lower with more family support.”

These parents and others shared some pointers with BuzzFeed News for raising a transgender kid, from finding a medically sound therapist to reckoning with religion.

They also included this piece of advice for parents: Learn these lessons now — even if you don't have a transgender child — so if someone in the family does come out, you know how to make the right choice right away.

Listen to children who are insistent about their gender identity.

Kids exhibiting behaviors outside gender norms is typical, such as a boy doting over a doll, but that doesn't mean they are transgender, said Moss. Her child announced he was a boy at the age of 7 or 8. After a few years of uncertainty and depression, Moss recalled, her child called home "crying on phone and said, 'I am a boy, not a girl. I would rather face all the bullying in the world than force myself to be a girl.”

"If that child's behavior is insistent, consistent, and persistent," she said, "it is much more likely your child is transgender."

Jackson, whose daughter came out at the age of 4 and lives as a girl with her family in Kansas City, Missouri, said, "My advice is to listen to them. They need to know that they have someone in their life supporting them.

“It really ought to be their parents,” she stressed, “because they are going to face so many struggles — from friends who don't understand them to employers who don't want to hire them. Society makes fun of them; they are the butt of jokes in TV and movies. There is so much going against someone who is transgender and they need one person who they can count on 100%. That's our job as parents anyway."

Talking openly is proven to improve outcomes, said Ryan, the clinical therapist. "Our research shows [these conversations] help protect against risk and help promote well-being. Let a child talk without interrupting them or punishing them, and let them explain what their experiences are like."

Interpret your religion yourself.

"I think most Christian parents and parents of faith with a transgender child ask the questions, 'How could God make a mistake?', or, 'Did God make a mistake?'" said Ray Dever, an ordained Catholic deacon at St. Paul Catholic Church in Tampa, Florida.

When his daughter came out as transgender at 19, Dever said, he and his wife prayed "for understanding, for clarity. We came to the conclusion that God didn't make a mistake. This is our child. Our child is the same person we had known and loved her whole life."

Christian families can often be torn between their child and religious leaders, Dever said. "There are complex moral and theological issues that churches wrangle with, and parents are getting mixed messages. There is discussion that all LGBT people are fundamentally disordered. I think a lot of parents feel guilty — what am I supposed to do, and what would the church want me to do? I'm sure they are trying to love their children and also listen to their faith and their churches."

At the same time, though, Dever was careful to avoid condemning the Alcorn family or saying that they should have done something different. He did warn that looking for "a verse or a line in the Bible that you think speaks to that particular situation is dangerous. It needs to be taken in the context of the entire scripture and faith." Even though the message of Jesus is one of inclusion, he said, some religious leaders have a "tendency to exclude people who should be included in the tent. I think they can go back to the gospel, and the conclusion is to love your children first and foremost."

Separate religion from medicine.

"I was raised Southern Baptist," said Jackson. But after church leaders recently issued a statement condemning LGBT people, Jackson stopped identifying herself with the church because she never wanted her daughter to think “I had aligned myself with those views.” Jackson said she is still Christian, although nondenominational and possibly willing to vote for Democrats who support LGBT rights. "For me it’s about personal faith."

When looking for guidance on raising kids, she said, "I don’t want a book written by people who have never met that child and interpreted by people who never met that child.”

“We don’t blame God or condemn children born with other issues; we don’t deny them medical care.”

A geology major in college, Jackson said she trusts science and medicine above biblical literalism. "We don't blame God or condemn children born with other issues; we don't deny them medical care," she said. "It should be no different for any child born gay or transgender. … When we deny who they are and force them to be someone they aren't, they deal with depression, they deal with self-harm if not suicide, they turn to sex work and drugs."

The trick, said therapist Ryan, is ensuring that religious families understand being transgender can be a normal part of human development. "They don’t understand it from a medical perspective," she said. "They understand it from a cultural perspective. They are seeing it as their child violating cultural norms."

The Family Acceptance Project publishes booklets tailored to people of diverse cultural backgrounds, from Spanish speakers to Mormons, that explain science and statistics on transgender people in a nonconfrontational way. "Your child is not being rebellious, immoral, or willful," Ryan said she tells these families. "You may perceive that this is against your faith, but it’s not against your faith."

Take your kid to a therapist (and take yourself to one, too).

When a young person shows "consistent, insistent, and persistent" behavior that suggests a child may be transgender, "get them their own therapist to talk to," said Moss, the mom in New York. "And one who is supportive. There are some who are hostile."

Although some therapists wear a straitjacket of religious ideology, she said, a medically sound therapist who specializes in these issues can diagnose a child with gender dysphoria, the technical term for someone whose true gender identity does not match the gender they were assigned at birth. That therapist can help the child open up, evaluate his or her mental state, and recommend next steps for everyone in the family.

But the parent may need more. "You may need to get therapy for yourself and realize that it's not really about you," Moss said. "I felt grief for losing what I thought was my daughter."

Everyone interviewed for this article suggested conducting research online, joining support groups, or reaching out to online forums for kinship with other parents. One such forum is a 1,300-person Facebook group administered by Moss called Parents of Transgender Children.

This sort of counseling and learning can help parents avoid sending messages of rejection. "Get therapy and find a way to come around," said Jackson, "because otherwise you will be burying your child in no time, and that is a risk I am never going to take.”

Remember that it is normal for this to be difficult.

"This is not easy for any parent," Jackson acknowledged. Parents can ask themselves questions, she said, such as, "Is this too big of a decision for a child to make at this age? Are we leading them? Maybe they are just an effeminate gay boy and not a girl. Even the most liberal, open-minded people have admitted to struggling.

"People think, you're all permissive liberals, so you change pronouns and go buy a new wardrobe — no,” she stopped. “This is a process. By the time kids are verbalizing, they have been processing it for a while. They may want to go fast, but it's the parents who are saying, ‘Slow down, you've got to give me some time.’”

Jackson explained her child's adjustment like this: "It was wearing one princess dress, and then it was getting a pair of shoes that had pink and glitter on them.” Eventually her daughter was wearing dresses more and becoming happier. "It's all gradual steps," Jackson said. "It's us saying we believe who you are.”

But even then, there were sticking points. "The biggest struggle for me was underwear — to go and buy underwear with princesses on it and put it on my little boy's anatomy was the biggest struggle for me,” Jackson said. “It took like, three weeks.”

Then she hit what she called an “aha” moment.

“Why do we care?” she said she thought one day. “It would make her happy, and no one is going to see it because she will have clothes on top. And no one will know what's in her underwear, so that was a big aha. Gender is not anatomy. She says she is female. We don't know why. She is happy. She is not talking about dying and not having the right body anymore."

Defend your child from bullies (even if they are school officials or family members).

Ryan, who has worked on LGBT health and mental health for 40 years, said parents need to "stand up for their child when others mistreat them because of who they are."

This includes people closest to the child. "I think that many people worry about their extended family and friends not accepting a transgender person in the family," said Dever, the deacon. While his family was supportive, he said, "You can tell that there is some discomfort with some people.

"They are the same nephew, niece, grandson, or granddaughter they have always loved. I think you just have to do the right thing. And if that ends up damaging other relationships, it just happens."

Parents can help their child update IDs, social security cards, passports, and, in some jurisdictions, birth certificates to reflect their child's gender identity. But one of the most difficult places for parents to help their children find institutional acceptance is in schools.

Consider Jolene Smyers, who joined her son Rubin's fight to let him use the boys restroom at his public high school New Jersey. Officials had banned him from using the boys restroom, in violation of state and federal law. Jolene attended meetings and backed up Rubin in an ultimately successful battle to use the restroom that conformed with his gender identity. "I had been in school trying to reason with these people," she told BuzzFeed News in December. "I felt they were undermining his self-esteem and confidence. It was upsetting to him, and it was upsetting for us."

She added about her son: "It was a courageous thing to come out and reveal his true persona."

And Rubin, who also ran a petition to use the boys restroom, feels similarly positive about his parents: "My parents have been massively supportive," he said. "I am very lucky to have the parents that I have."

This stands in stark contrast with Alcorn’s suicide note, which begged readers to help “fix society.” With his parents' support, Rubin Smyers had the freedom and support to fix one part of society himself.

Help their transition.

The media and public often focus on the physical elements of a gender transition — from clothes and hair to physical anatomy — but for many parents, this focus came after basics like open conversations and social affirmation. Still, gender is largely conveyed physically.

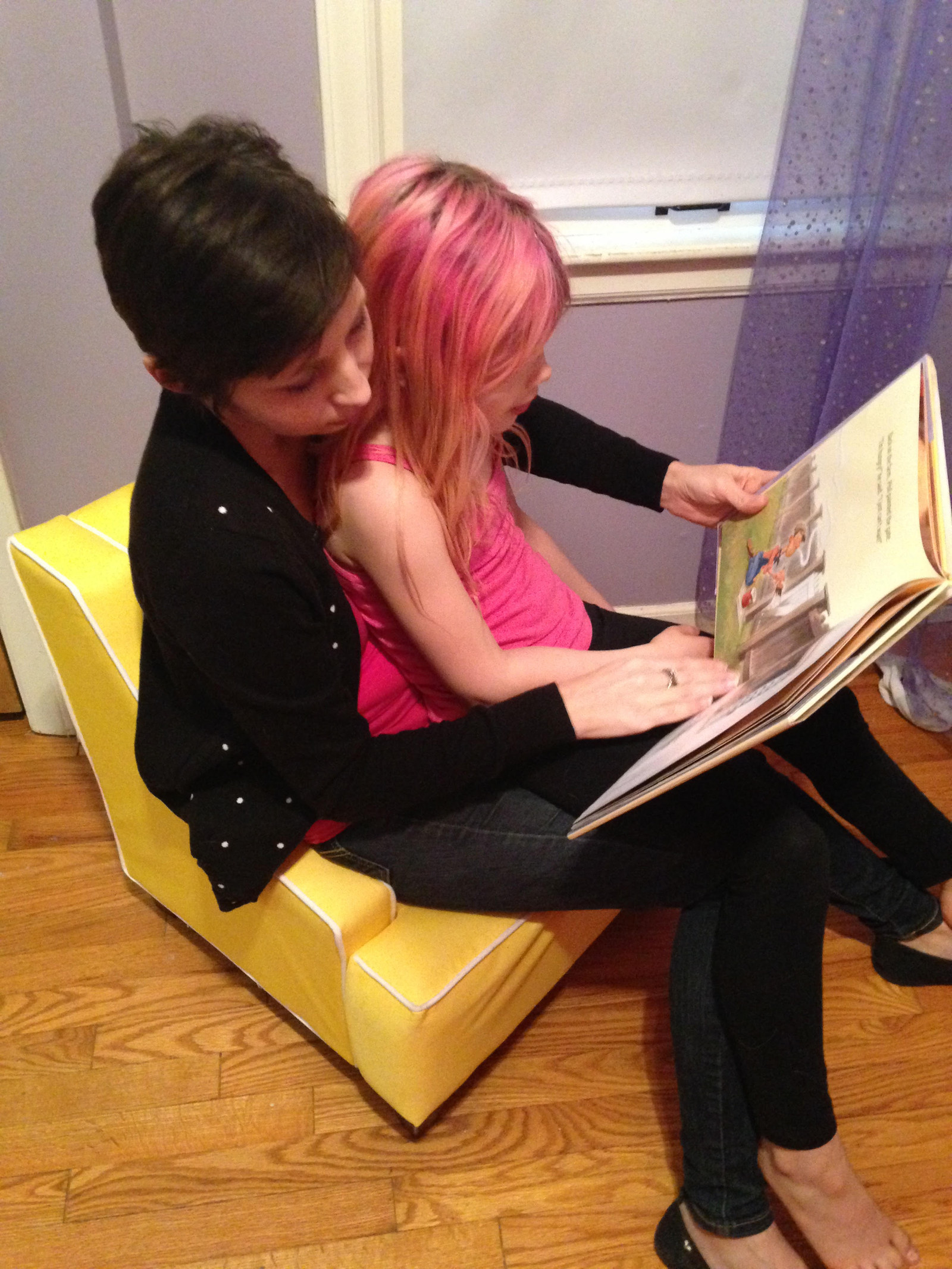

After deciding she would support her child's transition, Moss recalled, "That night we went out and got a bunch of boys clothes. Within a week, we went and got his hair cut short. As parent of a transgender kid, at first it is very daunting, but one of the reasons you feel good about this is because as we started to do this, he just lightened up. It was like a weight was lifting off his shoulders and he started to become happier. So then we kept taking more and more steps, and each time along the way, he just got happier."

They visited a therapist and eventually an endocrinologist who started her child on hormone blockers. At the age of 15, last year, her son got so-called top surgery to make his chest more masculine: "That was probably the happiest I have ever seen him — to have his chest."

"Now one room is blue with skateboards on the wall and one is pink with princesses on the wall."

Some of the physical changes are environmental.

Jackson used to have two boys who shared a room, she said, but after one came out as female at the age of 4, they made a gradual transition that, given the child's age, did not include surgery or hormones, but did involve growing out her hair, picking new clothes, and redecorating the kids’ bedrooms. "Now one room is blue with skateboards on the wall and one is pink with princesses on the wall. That's just our life. We're just as Norman Rockwell as anyone else."

Even if parents or friends cannot afford physical objects of a transition, Moss said there are other ways to affirm a child's gender. "For a transgender girl, say a small compliment, like, 'You look so pretty.' You are affirming that you accept them for who that are. Or say, ‘What a handsome young man you are turning into.'"

Help your kids stay safe.

Transgender women in particular have extraordinarily high rates of assault and homicide. In Ohio, where Alcorn lived, four hate-motivated homicides of transgender women were reported in the last two years. In 2013, there were 14 reported incidents of non-fatal hate-motivated attacks on transgender people in the state. "If you are a parent and your child comes out, that is one of the first thoughts that comes to your mind," said Jackson. "I don't want my child to get murdered."

Among the most basic measures to avoid violence is keeping a child out of harm’s way by ensuring they live at home. An October report by the Family and Youth Services Bureau found that transgender youth make up 6.8% of all homeless youth. In comparison, a 2011 Williams Institute study estimates only 0.3% of adults are transgender. Those figures seem to affirm numerous studies that find that LGBT youth, particularly those rejected by families, have far higher rates of ending up on the streets, where they are subject to higher risk.

LGBT “adolescents left home more frequently, were victimized more often, used highly addictive substances more frequently, had higher rates of psychopathology, and had more sexual partners than heterosexual adolescents,” said a 2002 report published in the American Journal of Public Health that compared LGBT homeless youth with their straight and cisgender counterparts.

Safety can apply to younger kids, too, said Jackson. She said it was important that other people could not use the knowledge that her daughter is transgender to blackmail her. "We make sure that she knows anatomy is a private issue, but it is not a secret," Jackson said. "We don't want to say that she can't tell people or confide in friends [that she is transgender], so that they can't hold that over her head to get something."

You can't make your child transgender, but you can learn too late.

"You can't make your child be something that they are not," Ryan explained. "Toys and enabling a child to explore, especially in their play, are important ways of supporting a child's creativity." On the other hand, she said, parents who do not support a child who may be transgender "are increasing the risk of suicide, depression, despair, and increased family conflict."

“Why didn’t the nurse tell me this could happen in our family when I took my baby home from the hospital?”

But many parents learn this only after rejecting a transgender child when families, amid crisis, reach out for help. "We have got to get accurate information to parents, families, and religious leaders, but we are getting it to them too late," Ryan said. "This needs to be part of baby care and early childhood education. People express gender as toddlers."

Ryan drove this point home in a 2013 report titled "Generating a Revolution in Prevention, Wellness & Care for LGBT Children & Youth" in which she detailed reactions from parents involved in her research.

"Nearly every family in our study has said that 'We needed to know this information when our child was little.' Or, ‘Why didn't the nurse tell me this could happen in our family when I took my baby home from the hospital?'" the report notes.

Jackson reflected on a conversation in which she considered the potential ramifications of affirming her child's gender identity while she was so young. "The therapist said, 'What is the worst that could happen?'" Jackson recalled. "'If it relieves stress now, maybe she will want to transition back in a few years. Isn’t that easy? Cut her hair and put boys clothes on.

"The alternative," Jackson said, "is a child talking about death more and more."