The house juts its chest out of the Hollywood Hills, flexing more bravado than actual confidence, looking a little unsteady as if one more misstep, one more bad night, could send it tumbling onto Sunset Boulevard. Sure, it’s got flair — the Spanish tile roof, the massive double balconies lording over West Hollywood — but, really, this house is peacocking, begging you to pay attention to it.

Stand on one of those back balconies, look down on the Comedy Store, the Sunset Strip, the Los Angeles Basin, and, on a clear day, maybe even out to the Pacific, and you’ll succumb to the illusion that this town is just out there waiting for you, that it wants you, even needs you. But this house was built on the hopes and dreams of the people who forgot that. It nurtured them — with shelter, camaraderie, laughs, sex, drugs — until it didn’t.

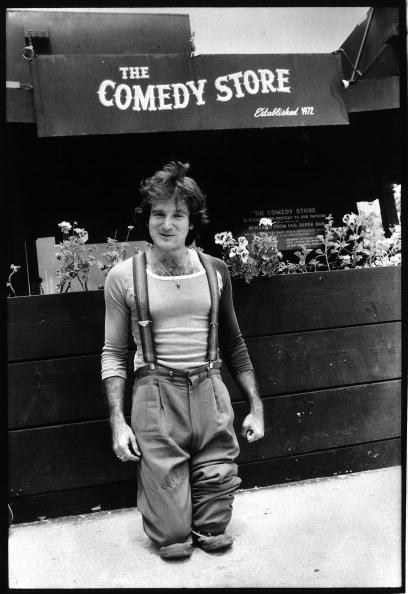

Stand-up comedy has been born and died a thousand times within a few hundred yards of 8420 Cresthill Road. Some of these deaths have been literal: In 1979, Steve Lubetkin, a struggling stand-up, dove off the roof of the Continental Hyatt House hotel and landed in the Comedy Store parking lot. Three years later, John Belushi died in Bungalow 3 of the Chateau Marmont, just up the road, after capping off a night of partying with a toxic speedball. Many more births and deaths have been figurative, onstage at the Store: Comics like David Letterman, Jay Leno, Sam Kinison, Andrew Dice Clay, Jim Carrey, Roseanne Barr, and Marc Maron found their voices here; many more, whose names have been mostly lost to history, shouted into the darkness of the Original Room and heard no reply.

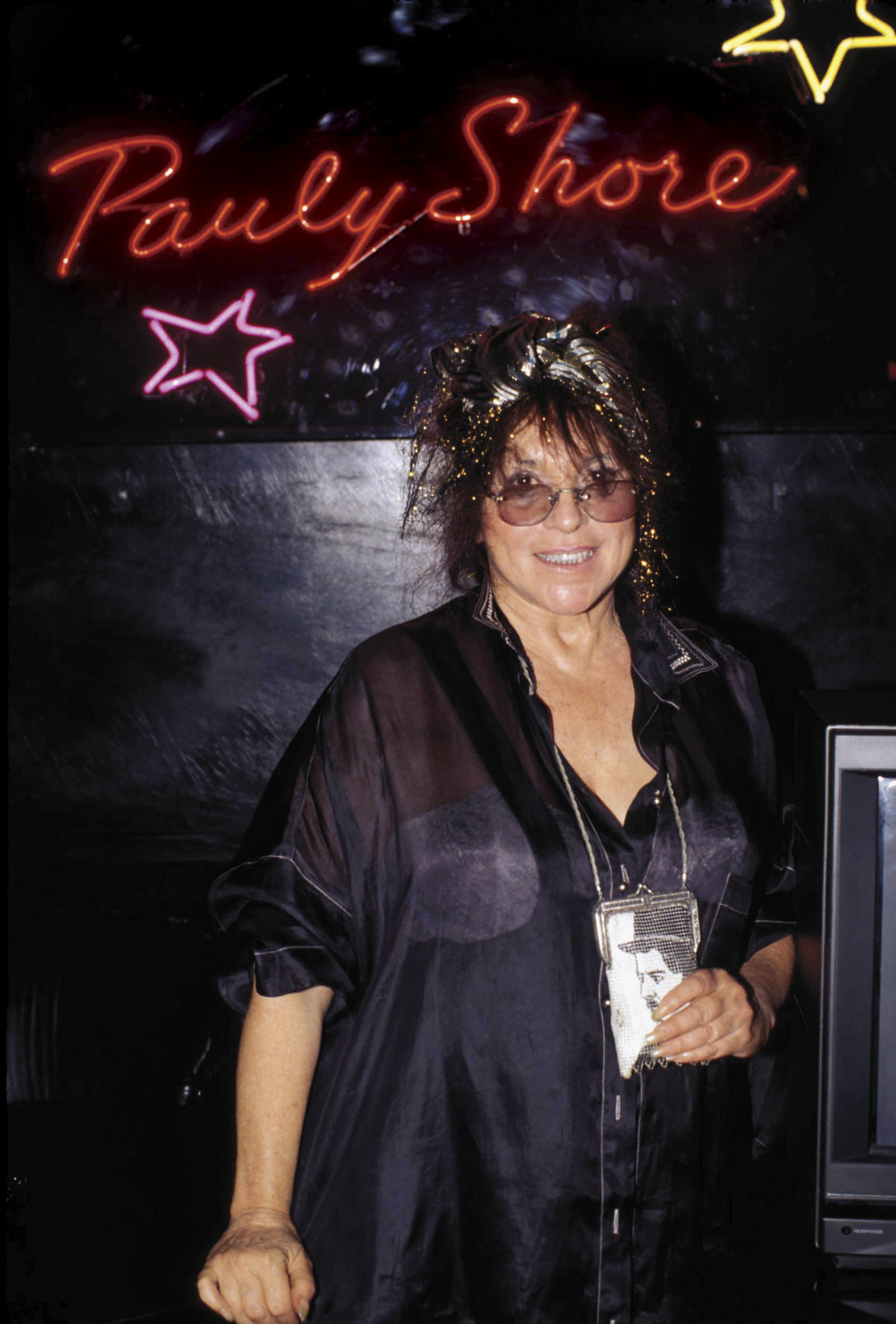

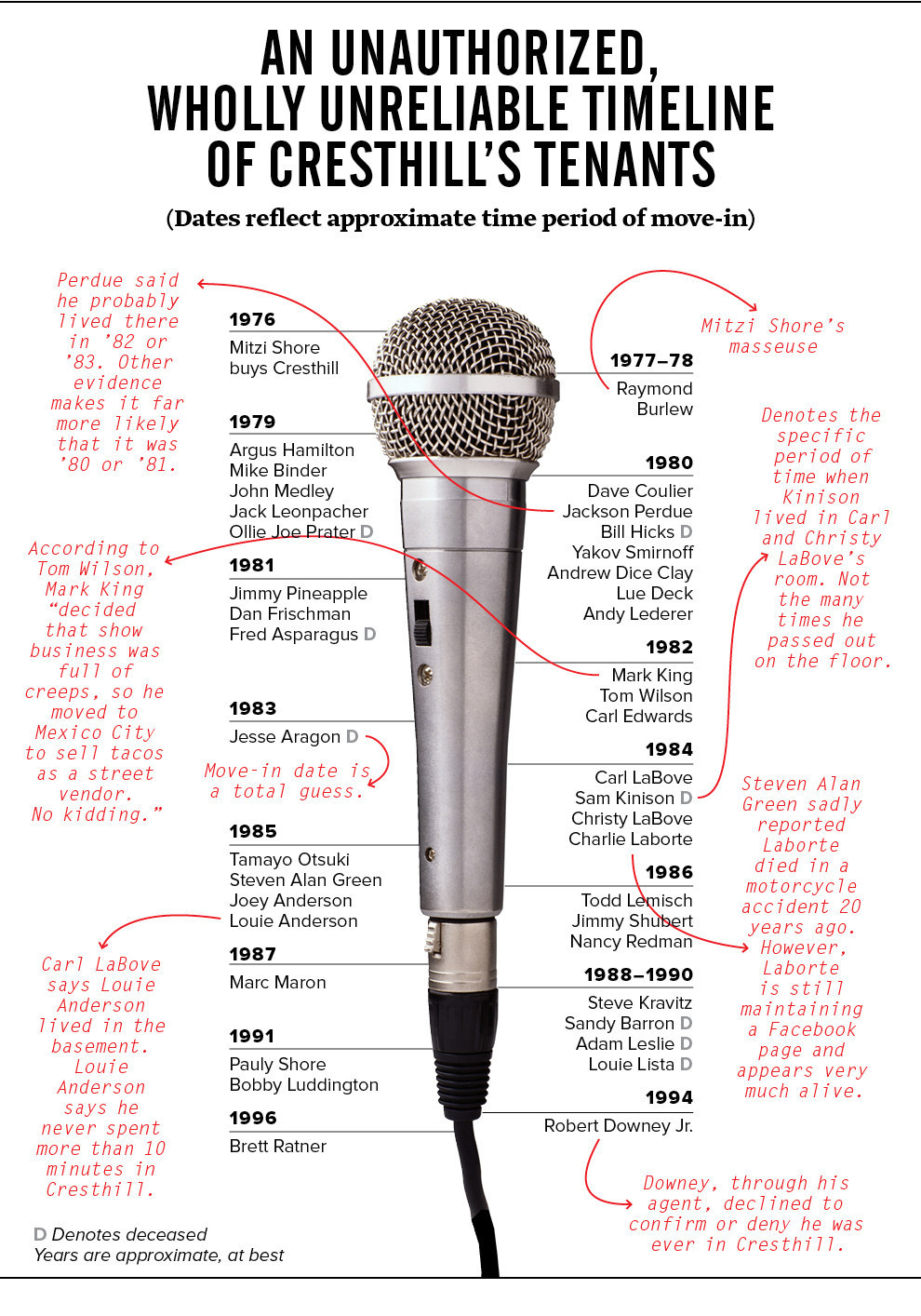

In 1976, when Mitzi Shore, the Comedy Store’s owner and enigmatic doyen (and mother of Pauly), bought the club, Cresthill, as it came to be known, was rolled into the deal. From the front, the house looks kind of small, almost humble. The two largest bedrooms are on the street level, and it isn’t until you descend the staircase and walk toward the back of the house that the three-story, nearly 5,000-square-foot abode begins to reveal itself. The space widens and draws you toward its oddly placed alcoves, its nooks and crannies, toward those sweeping balconies, toward its secrets. Built in the 1920s, the place has a shadowy history dating to the days when the mob and the Rat Pack prowled the Strip. At the time when Mitzi bought it, the house — which sits on a cul-de-sac of pretty, older homes elbowing each other for space — was vacant, and at first, Mitzi did little with it. Then, around the time of Lubetkin’s suicide, she essentially gave the place over to the comedians who worked at the Store.

For about a decade, comics inhabited Cresthill. Inhabit is the best way to put it, really: Some had their own rooms, some of those actually paid some token rent, but many, many more were just kind of there — to hang out, to drink, to do drugs, to talk shit, to crash on a couch, or a floor, wherever. There were three bedrooms, maybe four, depending on what you’d call a bedroom, but that had little relation to how many people might be sleeping there at any given moment. No one can remember ever signing a lease.

"COMICS WERE ALL OF A SUDDEN GETTING RESPECT, SO WE COULD GET AWAY WITH MURDER. AND WE DID."

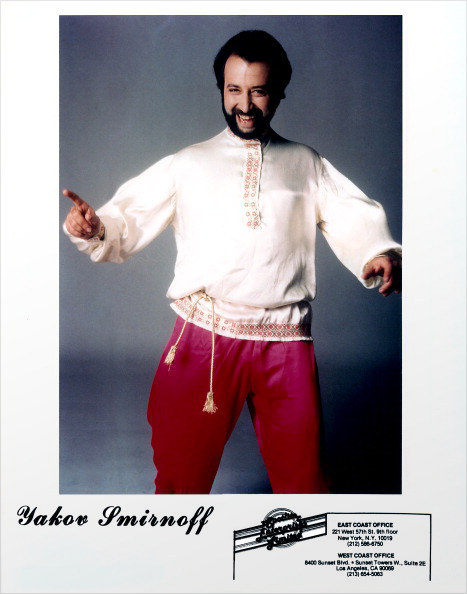

The catalog of names is impressive: Dice, Kinison, Carrey, Maron, Robin Williams, Richard Pryor, Yakov Smirnoff, and Bill Hicks all either lived there or hung out there between 1979 and 1989. Some — like Dice and Kinison — were around for more of those years than they weren’t. Allan Stephan, a comic who was part of Kinison’s “Outlaws of Comedy” crew and later the showrunner for Roseanne, never lived in Cresthill but spent countless hours there in the late ’70s and early ’80s. “Comics were all of a sudden getting respect, so we could get away with murder," Stephan says. "And we did.” Mitzi saw the Store as a place for comics to work out and improve, essentially comedy college. “Cresthill,” Stephan says, “was the frat house.”

The place is more than an interesting footnote in comedy history: Cresthill’s glory years coincided with a massive stand-up boom across the country. In the mid-’70s, you could count the number of comedy clubs nationwide on one hand; by the late ’80s, there were hundreds. This group of comics, haunting Cresthill, working the Store, helped to create the stand-up business as we know it. In that house, these comics forged a style and, more important, a bold, anarchic attitude that still pervades comedy today. But this came at a cost: Maron, who showed up around 1987 and lasted eight months living in a small room Dice had recently vacated, described his time there to me as a “big, dark baptism.”

Unsurprisingly, specifics can be a bit murky when it comes to piecing together Cresthill's history. Want to know how long Bill Hicks crashed there or whether Eric Clapton really jammed up there one night? Ask five comics and you’ll likely get five different answers. It’s not that people are lying — though, sure, some may be — so much as time and the fog of booze and drugs tends to obscure some details. Still, that haze — a hybrid of truths, best guesses, misremembered recollections, and outright tall tales — adds up to a stew of memory and myth that’s no less real than a notarized legal document.

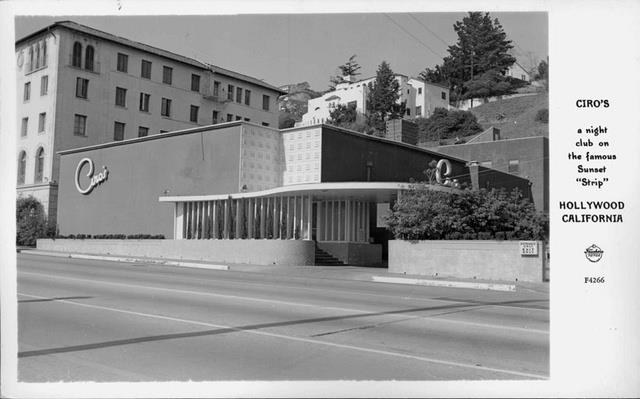

In the early ’70s, what little stand-up business there was revolved around two cities: Las Vegas and New York. But in April 1972, an old-school comic named Sammy Shore opened the Comedy Store in a 99-seat room in a building on Sunset Boulevard that had once housed the venerable Hollywood nightclub Ciro’s. In May, Johnny Carson decided to move The Tonight Show from New York to Burbank, California.

In its early days, the Comedy Store was more a clubhouse for Sammy and fellow comics like Shecky Greene and Jackie Vernon. But The Tonight Show’s move west brought in a newer generation — Robert Klein, George Carlin, David Brenner. When, in 1973, a set at the Store by young then-unknown Freddie Prinze won him a spot on The Tonight Show, it was a signal of comedy’s tectonic shift from New York to L.A. — and of the beginning of the Store’s rise.

The Store earned cachet on Sammy’s watch, but he was a comic with little interest in running a business. There were no set schedules; he and his friends got stage time whenever they wanted. He was frequently on the road, and when he was, his wife Mitzi took over. She wrote out a lineup every night. She instituted an open-mic night for amateurs looking to take their shot. She rebuilt the room to focus everyone’s attention on the stage, took out the bar, and made customers order drinks from the waitresses, establishing the two-drink minimum that became de rigeur in clubs nationwide. Essentially, she invented the modern comedy club.

When she and Sammy divorced in 1974, he gave her the club to lower his alimony payments; two years later, after being briefly evicted (and opening a new Comedy Store location in Westwood), she negotiated a deal to buy the entire building — plus Cresthill. In her words, Mitzi grew up as, “the only Jew in Green Bay,” Wisconsin. Nobody who knows her, it seems, can talk about her without lapsing into an impression of her thin, perpetually unimpressed, nasally whine of a voice. (Shore, 85, has Parkinson’s disease and other neurological issues and was unavailable to be interviewed.) Somehow, running the Comedy Store suited Mitzi’s oddball personality.

The club became ground zero for stand-up in the late ’70s: Leno, Letterman, Pryor, Williams, Michael Keaton, Jimmie Walker, Richard Lewis, Richard Belzer, Elayne Boosler, Paul Mooney, Garry Shandling, and Marsha Warfield all considered the place something of a home base, and others like Carlin, Steve Martin, Billy Crystal, and Gabe Kaplan were consistent visitors. Hollywood talent scouts lurked: The prizes weren’t only shots on Carson; networks were signing comics to develop sitcoms.

Mitzi saw herself as the scene’s munificent den mother. She made calls on behalf of comedians she thought deserved a look. She loaned them money. She took some on vacations with her. One person I spoke to who worked at the Store during this era tells me he was ferrying $20,000 in cash back to her house to put in her safe every night.

But if there’s one truism about Hollywood, it’s that behind every big success are dozens of people feeling aggrieved about it. Which isn’t to say that the comics who went on strike at the Store in 1979 didn’t have a legitimate gripe. Mitzi was making money by the satchel, and the regulars who performed at the Store weren’t getting paid. She considered the club a “showcase” room, an opportunity for comics to develop their acts and get discovered. That’s the way it worked. This wasn’t totally self-serving: Prinze got Chico and the Man. Walker got Good Times. Williams got Mork and Mindy. But it was a little self-serving: Paying customers would hardly be lining the sidewalks waiting to get in without comics onstage.

Nobody, least of all Mitzi, figured the rabble of comedians could organize a real work stoppage, but for about six weeks in the spring of 1979, they did. Guys like Letterman and Leno, already flush with their first successes, picketed alongside their less well-known colleagues. Mitzi felt betrayed. A handful of comics crossed the picket lines, simultaneously earning her enduring affection and the barbed scorn of their fellow comics.

The strike would be settled by June. Mitzi caved — a little — setting up a payment scheme so performers would get 50% of the door in the Main Room or $25 a set in the smaller Original Room. Some bad vibes certainly endured, but for most of the comics, there seemed to be palpable relief that the strike was over. The change in payment policy, however, was not the only by-product of the conflict.

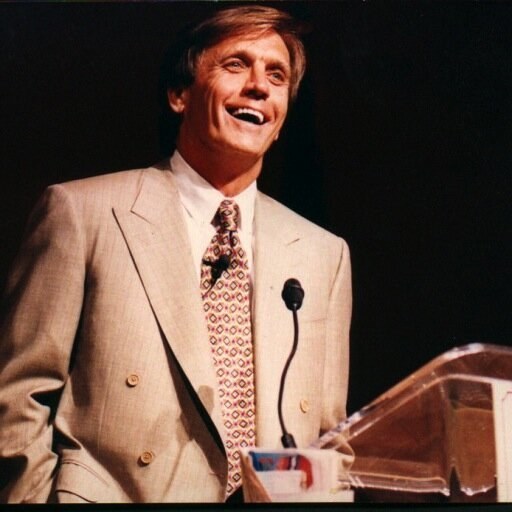

A long time ago, Argus Hamilton was the future of stand-up comedy. Some — including Hamilton himself — thought the former University of Oklahoma frat boy was going to be the next Carson, and he appeared on The Tonight Show more than 20 times before his career was derailed in the ’80s by a crippling fondness for cocaine and booze.

Hamilton was the first comic to move into Cresthill in the summer of 1979, along with a young comedian from Detroit named Mike Binder, whom everyone called “Kid Comedy,” and John Medley, an actor and bartender Hamilton knew from Oklahoma. Hamilton lived there until 1982 and then returned for a few months in 1986. Much of the time he wasn’t at Cresthill he was either in rehab or staying with Mitzi, who was his on-again, off-again girlfriend for many years and with whom he’s still close. He’s seen among the former Cresthill gang as the unofficial keeper of the flame. In interview after interview, whenever the thread of a story got lost, I was advised to “ask Argus.”

I meet him on a Sunday afternoon in the parking lot behind the Comedy Store, where Hamilton, who has been sober for 29 years, still performs regularly. We’d planned to talk inside the club, but after banging on the doors and getting no reply, we cross the parking lot and sit in the lobby of the Andaz West Hollywood, the hotel formerly known as the infamous Hyatt House. Cresthill, says Hamilton, wasn’t a reaction to Lubetkin’s suicide; it was a physical manifestation of the “postwar relief” that Mitzi and Store regulars felt after the strike. Mitzi wanted to do something to help the comics, particularly those like Hamilton and Binder, who’d crossed the picket lines. “She suggested that a few comics could live up there but she didn’t want it to turn into a flophouse,” Hamilton tells me.

The comedy landscape was changing then. “All these comedy clubs are popping up all over the country,” says Hamilton. "They’re paying Comedy Store guys $5,000 a week to go to Atlanta, to Houston. When rent is $200 a month, the phone bill is $15 a month, gas is 78 cents a gallon, and you make over $100,000 a year, you’ve got a lot of disposable income.” Much of which started going up people’s noses.

Binder, who later became best known as a writer/director/actor of films like The Upside of Anger and HBO's The Mind of the Married Man, says that while he lived there, the house and the Store felt like the center of the entertainment universe. “Robin had Mork and Mindy, Letterman started [guest-]hosting the Tonight Show, Michael Keaton and David were on Mary Tyler Moore’s variety show, Jimmie Walker had a series, I got this Norman Lear show called Apple Pie,” he says. “People magazine did a story, What’s Going on at the Comedy Store? So people started to come down. After we’d shut the club down, we’d be hanging with Willie Nelson, Burt Reynolds, Ringo Starr, Sugar Ray Leonard and partying. We couldn’t believe it. A lot of it took place after-hours in the Main Room, but most of the time, we’d shift it all up to Cresthill.”

Future Full House star Dave Coulier moved in for a few months in late 1979 or early 1980, and also recalls a somewhat mysterious housemate named Jack Leonpacher, who worked as a runner for Mitzi. “Jack stole all my clothes while I was on the road one week,” says Coulier. “He denied it and then showed up at the Westwood Comedy Store one night wearing one of my shirts.”

The next arrival at Cresthill was Russian comic Yakov Smirnoff. In the ’80s, at the height of Cold War paranoia, Smirnoff’s aw-shucks, “America, what a country!” shtick reassured a nation that its Reaganite vision of itself was righteous — and deflated the mighty Evil Empire of the Soviets into a laughable facade. He had his own TV show (What a Country), starred in films (Moscow on the Hudson, Brewster’s Millions, Heartburn) and was one of the country’s biggest stand-ups. But when he first showed up at the Store, he was just an émigré from the Ukraine with a shaky command of English. Mitzi liked him though and offered him spots onstage, work as a handyman, and a tiny room upstairs at Cresthill.

“Yakov was a master carpenter and plumber,” says Jimmie Walker, who didn’t really hang out at Cresthill but knew about it from performing at the Store. “Yakov fixed a lot of shit around the house. He did all the building around there.”

A few weeks after Smirnoff’s arrival, the house got another new initiate, a brash Brooklynite who performed as Andrew Clay. Smirnoff had met him already — they’d each done their first paid gig the same night at Rodney Dangerfield’s club in New York.

“He scared the shit out of me in Dangerfield’s,” Smirnoff tells me. “His persona was so big. Shortly after, I went to L.A. thinking I’ll never see him again. I was fine with that. Then, all of a sudden, I opened the door” — and with this Smirnoff slips into a pretty solid Dice impression, albeit still with traces of his Russian accent — “My man! Come ’ere! Gimme a hug! I’m gonna be yer roommate!”

Dice moved into the maid’s quarters, a small room off the kitchen with fire-engine red walls, red carpet, red furniture, and a window with bars on it that he once got a blow job through. Also crashing at Cresthill — though likely not paying rent — was Ollie Joe Prater, a 300-plus-pound, bearded Midwesterner whom Dice describes in his memoir, The Filthy Truth, as both “a party animal” and one of the “great comics you never heard of.”

At the time, despite his larger-than-life attitude, Dice onstage wasn’t quite yet Dice. He mostly did impressions of guys like John Travolta, Sylvester Stallone, and Elvis. “We all thought he was an idiot,” says Binder. “I mean, he was a sweet guy but he was just kind of a big doofus. We thought his act was like a fuckin’ circus act. Dice was just one of the characters he did.”

The house’s gravitational center and late-night gathering spot of choice was the massive oak table in the dining room. Two different comics compared it to the famed Algonquin Round Table, albeit with slightly more emphasis on strippers, drugs, and dick jokes. “We’d snort, smoke pot, drink beer, and talk comedy,” says Hamilton. “It was early enough in our disease where we shared our coke. Dice never drank or did drugs but loved to stay up and talk.”

One comic told me about a night, hanging out at the table, listening to Richard Pryor and Robin Williams trade stories and jabs. Stephan says that even though Pryor was already a huge star, he wasn’t above getting feedback and ideas from lowly Store comics. “He’d sit there and go, ‘What do you got for me?’” says Stephan. “We helped him with his specials. He had his clique but when blow was involved, he’d be around.”

Smirnoff wasn’t a partier. He’d go onstage early at the Store, then come home and go to bed. “Every morning, I’d get up early and they’d just finished partying,” he says. “And every morning there would be a mirror on the table. I didn’t know why. Why would somebody take the mirror off the wall and eat powdered doughnuts off the mirror? What a crazy American tradition! It was like a secret I wasn’t privy to because I didn’t stay up late.”

"WHY WOULD SOMEBODY TAKE THE MIRROR OFF THE WALL AND EAT DOUGHNUTS OFF THE MIRROR? WHAT A CRAZY AMERICAN TRADITION!"

Williams was already a star but would frequently turn up to do impromptu sets, then hit Cresthill afterward. “When we were there, Robin was there, partying a lot,” Binder recalls. “He’d really light it up. When he’d say, ‘I’m coming up to party tonight,’ he’d get even more girls and more people. Celebrities would come.”

Lue Deck, who — like many Store comics — also worked as a doorman at the club, had moved into a space in the basement of Cresthill by this time, and recalls that Williams, Andy Kaufman, and Rod Stewart used to come by the house to score coke. Simply being around stars helped younger guys like Smirnoff, who got a big break when Williams convinced director Paul Mazursky to come see him perform, leading to the part in Moscow on the Hudson.

“When you’re in proximity to the Store, in proximity to other comedians, right at the center of it, you can’t help but get better,” says Smirnoff. “If there was a casting call, you knew before anybody. You were next to whoever is doing something important. It’s the power of proximity.”

In 1979, Hamilton, Prater and another Store comic named Jim Varney — indelible to those who lived through the ’80s as the yokel Ernest “Know what I mean, Vern?” Worrell in a gaggle of dopey films and commercials — took a road trip to Houston to compete in a comedy competition.

“We’re backstage at this party afterwards and there’s a Houston real estate agent with this softball-sized rock of pure cocaine,” Hamilton says. “I’m sitting there looking at this massive rock and on the other side is this other face looking at it the same way. That’s Sam Kinison. First time we ever met.” Hamilton spent six days blowing it out in Houston with Kinison and a crew of other comics that included a young Bill Hicks. “Bill was very unhappy because his father didn’t want him to do stand-up. Somehow we worked it out — he was going to run away from home.”

Before returning to L.A., Hamilton told his new friends to find him at the Comedy Store if they ever made it out that way. Over the next year or so, a gaggle of Houston comics moved West: Kinison, Hicks, Dan Barton, Jimmy Pineapple, Carl LaBove, Riley Barber, Steve Epstein. Hicks, who’d evolve into a biting, sociopolitical monologist in the Lenny Bruce mold before dying of pancreatic cancer in 1994, was 18 at the time. Hamilton says he got Hicks a job as a doorman at the Store and agreed to “stash him in Cresthill. He hid from his parents. They didn’t know where he was.”

Binder’s drinking and drugging was already so bad that he decided to move out. He and Coulier got an apartment together. “When I left, Bill took my bedroom,” Binder says. Hicks, a relative teetotaler, never really became part of Cresthill’s hedonistic culture and soon found his own apartment.

Kinison, however, would come to define that culture. He was already an outsize personality when he arrived in L.A., but his act was a work in progress. He’d only recently given up his previous life as an evangelical preacher and brought that same stage presence to stand-up, although he didn’t always know what to do with it. But Mitzi hired him as a doorman and gave him keys to the Westwood location, where he frequently slept. He also began spending time at Cresthill, where he bonded with another charismatic character still honing his comedic chops: Dice.

As Dice put it in his book, “When we were still struggling comics, Sam and I had our own little two-man support group. Many were the nights when we’d go to Ralph’s grocery store, steal a bunch of pork chops, and head back to Cresthill, where we’d cook ‘em on the grill. After dinner we’d do routines for each other. We wouldn’t mince words. When I thought he should push it further, I said so. And the same for Sam.”

According to Dice, one night at Cresthill he demonstrated for Kinison how to build slowly to his trademark scream. “I helped Sam get his timing down,” he has said. “Kinison had a great opening line but didn’t know how to set it up. I showed him … I said, ‘You gotta put more theater into it … suck the audience in before you blow your stack’ … It was a killer opening that Sam used for most of his career.” In Dice’s telling, the night ended with both of them practicing Kinison’s scream back and forth over the kitchen table, waking Smirnoff in process.

Smirnoff recalls the events differently. He says Dice and Kinison were staging a fake fight that everyone at Cresthill thought was so funny that Smirnoff suggested Kinison try it onstage. “So we all walked down to the Comedy Store. It’s 1 in the morning and there’s a few people there, and he’s just in their face screaming, red in the face. The crowd is cracking up. That was a key turning point in his career.”

It’s worth noting that Kinison’s brother and then-manager, Bill, calls Dice’s claims “bullshit,” but regardless of the discrepancies over exactly what kind of impact Dice might’ve had on Kinison — and vice versa — Cresthill had become a kind of comedy laboratory. Bits were born from late-night bullshit sessions, jokes were tested and honed, and brutally honest criticism was the norm.

“You couldn’t have the ego and sensitivity,” says Stephan. “I remember at the time, I was very funny when I wasn’t onstage. I was sitting on the couch, holding court, and Argus went, ‘If you can do what you’re doing now onstage, nothing will stop you.’ It took me about three years to learn this lesson.”

But the drugs were starting to exact a toll. Binder had already bottomed out, and Hamilton seemed on track for an even uglier fate. Mitzi was worried about him. Dan Frischman, a comic who moved in around 1981 and later starred in Head of the Class, recalls, “She’d sometimes call me and ask if any nefarious looking people showed up, possibly to sell Argus drugs.”

Jackson Perdue, a young comic from Southern California, had taken to staying in Hamilton’s room when Hamilton was staying with Mitzi — which was 9 out of 10 nights on average, according to Perdue — and had been put in charge of babysitting two of Mitzi’s kids, Pauly and Peter, whom he’d occasionally bring to the house. “Wherever they wanted to go, whatever they wanted to do, my job was to take them there,” he says. “I was the one who named Pauly ‘The Weasel.’ He was 11. And he was a little fucking weasel.”

The house’s roster was shuffling. Prater was on the outs with Mitzi and got booted. In came Frischman, and later, Jimmy Pineapple, a New Yorker named Andy Lederer, and Mark King, a sketch performer. In 1982, Hamilton went to rehab and Tom Wilson — then a young comic, now an actor best known for playing Biff in the Back to the Future films — moved into Hamilton’s old bedroom.

“Before talk show appearances, Yakov would have me act as Carson or Merv Griffin so he could practice his panel banter,” Wilson says. “I also helped Yakov carry an eight-foot-tall painting of himself into the entryway and hang it over the main staircase.”

Frischman says Dice “was a good housemate, but he’d get angry because most of the comics wouldn’t wash their dishes. They’d leave the kitchen a mess. When he’d bring women home, he’d have to go through the kitchen. One morning, he starts screaming, ‘The dishes go out the window in five minutes!’ Right outside the kitchen was an open-air atrium, and sure enough, all of a sudden, you hear crashing. He threw all the plates and pans out the window!”

Considering all the insanity in the house, its residents had surprisingly little trouble from the neighbors. The houses weren’t far apart, but because of the steep slope and the way Cresthill was built into it, much of the noise wafted down toward the Store, the Strip, and the city at large. For a while, the supermodel Twiggy lived across the street and would occasionally accept comics’ invitations to show up to the Store. Wilson recalls meeting a very old man who lived farther up the hill and relayed Cresthill’s pre–Comedy Store history.

“Even in the ’40s and ’50s, the house was full of gambling and debauchery,” Wilson says the man told him. “The house was owned by Ciro’s, and Ciro’s paid him to let a guy sit at his house and watch Sunset Boulevard and Queens Road for cops. If a raid was coming, he’d call Cresthill and the poker game would vanish.”

This is one point where the facts get slippery. Several comics I interviewed passed on stories of Cresthill’s early days. Pineapple tells me he got a huge kick out of the fact that guys like Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and Jerry Lewis used to party there during the Ciro’s era. Other rumors had it that Milton Berle and Redd Foxx were frequent guests. One comic told me the place had been a mob house, where “the mob took people and gave them a little bit of an education.” Supposedly, there was even a secret tunnel connecting the basement with the Comedy Store’s basement.

Few people from the ’40s and ’50s are still around, but George Schlatter, the general manager of Ciro’s from 1950 to 1957, had no memory of the house whatsoever. Neither did Sheila Weller, who wrote a memoir about her time as a child growing up around the club, which was owned by her uncle Herman Hover from 1942 to 1957. The few surviving performers from that era I was able to track down — Kim Novak, Rose Marie, Jerry Lewis, Debbie Reynolds — either didn’t recall the house or chose not to comment. But Ciro’s was a prime Hollywood hangout back then — Sinatra was famously arrested for punching a reporter there — so it doesn’t seem like a stretch that these same stars could’ve shifted the festivities to the owner’s house after-hours.

Frank Sennes, who revived the club in 1960, had previously been the entertainment director for several Las Vegas casinos and was well-acquainted with many of the Hollywood stars who frequented Ciro’s. He was also friendly with well-known gangster Moe Dalitz. The notorious L.A. mob figure Mickey Cohen was shot in front of Ciro’s in 1949, hung out at the club through the 1950s, and supposedly used its basement for all sorts of nefarious deeds. But it seems far-fetched that this could’ve ever been connected to Cresthill.

When I visit the house and head down to the basement, lo and behold, there’s a prominent trapdoor in the hardwood floor. Pulling it open, a wooden stepladder descends into a dark, dank cellar. Could this actually be the remnants of an old tunnel? I poke my head down but can’t see a thing. A few weeks later, I coax a local real estate agent to go down the ladder with a flashlight. He reports back no evidence of a tunnel, just a dirty crawl space filled with cobwebs. But is it possible there was once one there? “It’s unlikely,” he tells me, “but who knows?”

The truth behind these tales wasn’t the point for those who later lived in Cresthill. They felt true — and enhanced the house’s mystique. As Carl LaBove, who moved in there in 1984, put it, “There was a feeling there that it had always been that kind of house. You didn’t feel like you were doing something new. That’s what it was built for.”

It’s hard to pinpoint the moment when Cresthill really became Sam Kinison’s fiefdom. Even before his career took flight in the mid-’80s, Kinison’s charisma drew people to him, but LaBove was Kinison’s best friend. They’d moved to L.A. together and actively stoked a kind of mystical aura around themselves and whatever comics were in Kinison’s inner circle at a given moment. Rumors swirled that the two always carried guns. Mitzi had a rule that the house was for single comics — no girlfriends or wives allowed — but once LaBove moved in, his fiancé, Christy, and Kinison both surreptitiously followed.

Not everyone was thrilled with this arrangement. Wilson and, in particular, Dice, quickly grew weary of the drug-fueled, late-night, rock ’n’ roll circus–soap opera that trailed Kinison wherever he went. “Sam was someone whose natural state was chaos,” says Dan Barton, one of the Houston comics. “Dice was more orderly.”

By 1985, Kinison’s career was in the ascendency — his breakout performance on HBO’s Young Comedians Special had led to Carson and Letterman bookings, theater tours, and eventually a spot hosting Saturday Night Live the following year — but the rest of his life was a mess. His daily routine was to stay up all night, then sneak into LaBove’s room during the day to crash. (This unusual arrangement was even more unusual than it sounds: The year after Kinison’s death in 1992, LaBove discovered his and Christy’s daughter had actually been fathered by Kinison.)

After LaBove and Christy got married in 1985, they celebrated at Cresthill. “We had one of those blowouts that went to the following day,” says LaBove. “Everybody came: C.C. DeVille from Poison, Tommy Lee, all these guys. Dice wasn’t into drugs. Dice wanted to sleep. He just got tired of it. He got tired of the fact that we kind of controlled the house.”

Shortly after, LaBove got word that Mitzi wanted to see him. She’d heard Christy and Kinison were living in his room. All three would have to move out. Today. LaBove knew immediately who’d told her. “I was walking back up the hill. I’d made up my mind that I was going to kill Dice.”

While storming back toward Cresthill, he ran into Kinison, who talked him down. He had his own plan to get even. “Sam went to Dice and said, ‘I want you to know that we know it was you, and if I make it, I’m going to make sure I stick it up your ass every opportunity I get,’” he says. “This is the story that started the whole argument between Sam and Dice.”

Dice declined repeated entreaties to tell his side of it. But Jimmy Shubert, a comic who was tight with both Kinison and Dice, told me a version that mostly squares with LaBove’s. “Dice ratted Sam out,” says Shubert.

It can be hard to remember exactly how huge Dice and Kinison became in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and how much their feud defined stand-up during those years. Kinison broke first, scoring a memorable part in Rodney Dangerfield’s hit 1986 film, Back to School, making music videos and palling around with a debauched troupe of rock stars, porn stars, actors, comics, and whoever you'd consider Jessica Hahn to be. Dice became even bigger, appearing as a version of himself in a series of films (Making the Grade, Casual Sex?, The Adventures of Ford Fairlane) and selling out arenas. Their respective acts — heavy on testosterone-fueled bravado and ample doses of homophobia and misogyny — engendered controversy wherever they went.

Their bad blood spilled publicly. They’d badmouth each other on talk shows. Kinison would devote stage time to running Dice down. The adult film star Ron Jeremy was part of Kinison’s crew of misfits around this time and had known Dice from back in New York. “Right in the midst of their animosity, Sam comes up to me and says, ‘I just found out Dice is Jewish,’" says Jeremy. “‘I’m not going to call him Dice any longer. I’m going to call him Dreidel.’ So Sam called him Dreidel, and Dice told him to go fuck himself.”

In his book, Dice writes, “Sam was fixated on telling the world that I wasn’t shit. He went on [Howard] Stern and couldn’t stop ripping me. He started calling me Andrew Jew Silverstein, like I ever hid the fact that I was Jewish. He told a couple of audiences that he was hoping I died of inside-out stomach cancer.”

But the rivalry was somewhat one-sided. “Sam had a jealousy,” says Stephan. “He was a very insecure man with a lot of problems. He liked to fight and stir shit. He was a bully.”

Even Kinison’s brother Bill wanted to quash it. “I told him one time, ‘Why don’t you just shut up about Dice? You’re making the guy bigger.’” Bill tried to arrange for the rivals to tour together years later, but it only led to more animosity, and the two former friends were still estranged when Kinison was killed by a drunk driver on a highway outside Las Vegas in 1992.

LaBove, however, made amends with Dice years ago and now sees the whole episode differently. “Dice had every right in the world to complain,” he says. “Who can sleep when you’ve got a party going on downstairs every single night and it’s your house, too?”

Ironically, shortly after Kinison and LaBove were tossed from Cresthill, Dice moved out, and it wasn’t long before Kinison had worked himself back into Mitzi’s good graces and was again lording over the place. Kinison’s newfound stature attracted guys like Billy Idol, Ted Nugent, and Corey Feldman to the nightly ragers. Others, including Eric Clapton — whom Bill Kinison describes as Sam’s “best friend”— made appearances as well. A comic named Brian Seff, who performed as Rick Right, remembers seeing the famed guitarist jamming with Kinison and others at the house. “The cops came to complain about the noise and they didn’t recognize Clapton but recognized Sam,” says Seff.

As Feldman recalled in his memoir, “On any given night you might find as many as 10 or 12 comedians at Cresthill, crowded around the massive oak table, in the center of which was a mountain of cocaine. This was my introduction to the bacchanalian nature of Hollywood nightlife — half-naked women draped over fat, out-of-shape funnymen, booze and drugs flowing freely.”

And then there was Jim Carrey — another Kinison buddy who floated in and out of Cresthill but was never part of its debauched core. Back then, Carrey was an offbeat impressionist who’d already scored a Tonight Show spot and a short-lived network series, but his career was stalled. “Jim’s up partying with Sam and Carl, just being himself, being hilarious,” recalls Hamilton, who’d recently moved back into Cresthill at this time. “He’s at the table, complaining about his act he’s stuck in, and Sam says, ‘Well, drop that fucking act and be yourself. No matter how long it takes, you drop it right now.’ Jim goes to Mitzi and says, ‘I’m going to break out and be myself.’" He also met Damon Wayans around then, another late-night Store regular who would later recommend Carrey for his breakout gig on In Living Color.

Carrey is currently circling back near this time in his life for his latest project: executive-producing a Showtime original series based on William Knoedelseder’s history of the early L.A. comedy scene, I’m Dying Up Here, starring Melissa Leo as a Mitzi-like matriarch. The pilot is being shot this fall.

“I walked into a lot of ongoing stories,” Marc Maron tells me from his home — itself now a prestigious destination for comics — in Highland Park, California. Maron moved into Cresthill in 1987, dragging with him little more than a futon, a framed poster of the Tod Browning film Freaks, and a burgeoning cocaine habit. He fit right in.

Maron was working as a doorman, and his housemates included Shubert; another doorman named Todd Lemisch; Tamayo Otsuki, a Japanese comic who’d dated Kinison for a while; and a diminutive New Yorker named Nancy Redman. But it was still Kinison’s house.

“There was a night early on when I went one-on-one with Sam, doing blow and burning money,” Maron says. “I was being initiated into what would turn out to be the most disturbing and mentally destructive eight months of my life.” When the coke ran out, he drove Kinison to a dealer’s apartment, where Kinison downed several airplane bottles of Smirnoff before passing out. The dealer insisted Maron drag Kinison home. “He’s like, ‘I don’t want him to pull a Belushi on me.’ I get Sam in my car and bring him back to Cresthill, where he just lays face down on the living room floor and sleeps. He did that a lot.”

Maron quickly became, as he puts it, “the guy who hosted the parties Sam wanted to have. Monday nights, everyone would come from all over the dark crevices of Hollywood to see Sam.” These soirees sometimes lasted days. For Redman, one of the few women who ever lived at Cresthill, this sort of behavior quickly grew tedious.

“I didn’t do drugs,” she says. “I did decaf. When the parties were going on, I generally stayed in my room because I was trying to get to sleep.” Redman stopped short of calling Cresthill a boys club, but Sabrina Souiri, who worked for Kinison in the late ’80s and was later married to Stephan, describes it very much in those terms.

“It just seemed like a big frat house with a bunch of morons,” Souiri says. “I walked in one time and saw a bunch of comics doing blow and acting like idiots. It wasn’t a place I yearned to spend time.”

At this point, the house itself was starting to resemble its inhabitants: kind of haggard. Although Mitzi occasionally put money into it, collectively the comics took Cresthill for granted.

Alan Bursky, a longtime Store fixture who spent much time at Cresthill in the mid-’80s, recalls “the house being destroyed.” “The fireplace was gas and that pipe with the pilot-light flame was sticking straight out,” he says. “The oven looked like it’d been in a car accident. Guys were living in every nook and cranny. You went into the basement, in the corner, someone had a mattress or sleeping bag.”

It was like the place was straining to live up to its legend. Each new wave of comics was passing down the war stories — and attempting to outdo them. Mitzi generally kept her distance, but she was aware of the house’s reputation. For some time, she’d been trying to cash in on it by producing a sitcom about Cresthill. Barton was one of many who took a pass at writing a script in return for paying spots at the Store. Around 1987, a 12-minute pilot was actually shot — in Cresthill — that starred, among others, Otsuki and Redman.

Having managed to track down a copy, I can say without qualification that it’s pretty awful — and fails to capture the spirit of the place, the same kind of spirit that had been luring the talented, the desperate, and the slightly unhinged to California for decades. Even listening to comics talk about Cresthill 30 years later, I can hear them grasping to squeeze that magic between their fingers.

“That balcony was where dreams were made,” LaBove tells me. “I’d leave during the day, work as a doorman all night, do my spots, then come back and have a big party. We’d talk comedy until 4 in the morning on that balcony and look at the stars of the city. It was just a phenomenal way to celebrate your starving, celebrate what you’d given up for your dream.”

"IT WAS JUST A PHENOMENAL WAY TO CELEBRATE YOUR STARVING."

As Shubert puts it, “You only go through that once in your life. You only struggle like that once, when you give up everything to commit to your craft. You’re in this house, around all these great comedians, just immersing yourself in it.”

But for Maron, the dream was beginning to curdle. “I was sleep-deprived and starting to lose my mind,” he says. “I started to hear voices in my head, to see the Store as this vast, weird part of some dark, mystical conspiracy.” Kinison was out of control, frequently rampaging through Cresthill and the Store in a cocaine-fueled frenzy. He was prone to violent outbursts against pretty much anyone unfortunate enough to be standing nearby. At one party, Kinison smacked around the Store’s booker then kissed him on the mouth. At another, a girl passed out on a bed and Kinison pissed on her. “It was fucked-up shit,” says Maron.

One evening, Kinison put his guitar and amps into Maron’s room for safekeeping. A little later, a guy named Dave, who was known as a Satan-worshipping heroin addict, got into an argument with Kinison. Kinison threw a drink in his face, hit him a few times, and ripped Dave’s shirt off. Shubert recalls Dave being dangled off the back balcony by his ankles. Despite the obvious bad vibes, Dave refused to leave. Maron tried to manage the situation and told him to go hang out in his room and lock the door.

After that, Maron himself left to go pick up his friend Bill at the airport and didn’t return until the following morning. “I walk in with Bill, who I’ve told all about this amazing place and the time I’m having with Sam and everybody,” he says. “I go to my room and see the door’s been kicked off the hinges. The guitars are gone.” At the dining room table, still at it from the night before, are Kinison, LaBove, and one or two others. “Sam goes, ‘I pissed on your bed, Maron. Wanna know why? Because you let that moron sleep with my guitars.’ I turned to my friend Bill and said, ‘I told you I knew him.’”

The incident marked the end for Maron. “By that point, I was sleeping in my closet anyway,” he says. “I was in mental trouble. I started realizing someone’s going to die, someone’s going to go down for real, and it could be me.” A few days later he had a breakdown in the Store parking lot. The guy he usually bought coke from suggested Maron get out of town. “If the drug dealer is telling you to leave, it’s time to leave.”

Cresthill was on a similar trajectory. Mitzi was increasingly fed up with the comics’ behavior. Drug use that could’ve once been chalked up to youthful exuberance now had the markings of full-blown addiction. It’s not totally clear what the final straw was — one comic says it was a particularly raucous party during which Kinison led revelers in tossing expensive pieces of furniture off the back deck — but by 1988, Mitzi decided enough was enough. The comics were told to get the hell out. The party was over.

What happened next was almost more bizarre than all that had happened before it. NBC had paid Mitzi a $400,000 advance for a Comedy Store 15th-anniversary special that would feature performances by Pryor, Williams, Letterman, Smirnoff, Shandling, and others. With that money, she paid what she must have considered penance for her years of enabling various comics’ drug problems: She turned Cresthill into a halfway house for comedians trying to get sober.

Mitzi had already paid for Hamilton and others to go to short-term treatment centers, but the results weren’t always encouraging. Hamilton, who was then sober, says that in late 1987, Mitzi accompanied him to an AA meeting to see him get his one-year sobriety cake: “I told her how much the three-month halfway house experience after my 28-day stay at Betty Ford helped to fortify my own sobriety.” Mitzi teamed with an accountant, a doctor, and Hamilton himself to form a foundation for comedians in recovery.

Steve Kravitz, a comic who was tight with both Williams and Kinison but was in the throes of a debilitating heroin addiction, was one of the first to move in. “When I went back to Cresthill, it was like a dorm, twin beds, three or four to a room,” he says. “A counselor with a medical license is on duty all day, a guy stayed there at night to make sure nobody hurts themselves. There was group therapy, everything you’d have in that environment.”

Eventually, the house’s residents included a poet, writers, dancers, and other performers. Kravitz credits the place with starting his recovery, but this incarnation of Cresthill was short-lived: Kravitz stayed six months and says the halfway house lasted only a few more past that. Others, including Hamilton, recall it continuing for a couple years.

Regardless, Mitzi pulled the plug because — depending on which theory you want to believe — either they ran out of comics to treat, the house had strayed from its initial mission by letting in non-comedians, she had financial problems, or some combination of the above. By the early ’90s, Cresthill had a new occupant: Mitzi’s son, Pauly.

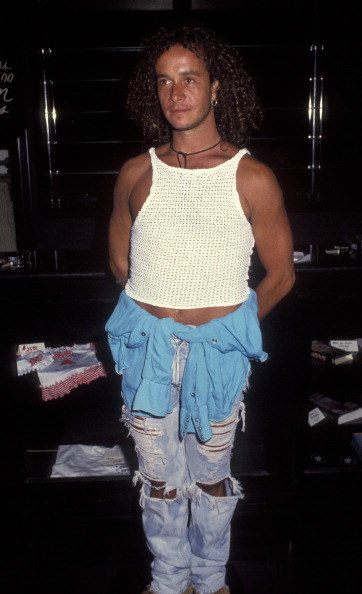

I meet Pauly Shore on a warm Saturday afternoon at Cresthill. He doesn’t live here anymore — he moved out in the late ’90s and his family sold the place, but as it happens, the house’s current owner, music producer Josh Abraham, recently listed it for sale with a price tag of just less than $3 million.

We meet at an open house. We’re the only two there, save for a tall, exceedingly helpful realtor named Steve. Pauly says he was hardly ever here during the wild ’80s — he was a teenager then — but made the place his own for about seven years in the ’90s, remodeling it and redecorating.

Wearing a red L.A. Clippers T-shirt, blue sweatpants, and Adidas flip-flops, Pauly sinks into a couch in an oak-paneled room that was once his assistant’s office. “I used to go out with a porno star named Savannah that killed herself,” he says. “We got that information in this room, actually. That was heavy shit.”

Pauly’s time at Cresthill was, as he puts it, “the heyday of [his] career.” He was on MTV, starring in movies — it was full-on Weasel-mania. Episodes of his show Totally Pauly were filmed here. His only consistent housemate was Bobby Luddington, a friend who also worked for him, though Brett Ratner had a room for several months during the year or so before Rush Hour made him an in-demand director. There was also a constant parade of guests, the recitation of which feels like its own time warp: Andy Dick, Stephen Baldwin, Anna Nicole Smith, late Alice in Chains lead singer Layne Staley, Joey Lauren Adams, Playboy Playmates the Barbie Twins. “I think there was even a point when Robert Downey Jr. stayed in the basement for a little during his drug time,” says Pauly. (Downey Jr., through his agent, declined to be interviewed.)

Pauly is understandably nostalgic for Cresthill, and after a while he talks to Steve with some degree of seriousness about buying it back. It’s been completely redone since his time here and would be almost unrecognizable to the comics who lived here in the ’80s. Walls have been knocked down; there’s a gym in the basement; Abraham flattened the steep hill behind the house to create a grassy backyard.

But hints of Cresthill’s history, its myths, still poke through. The room off the kitchen where Dice and Maron lived retains some seedy charm. Upstairs, a huge full-length mirror leans against a bedroom wall. It can’t be the same one comics used to pull down to snort blow off, can it? Surely the grand wooden dining room table hasn’t been there this long — and that trapdoor in the basement leads nowhere other than to a damp crawl space. Or does it?

Maron says that Cresthill taught him just how far a comedian could go, onstage and off. “If you want to push the limits and the boundaries, there’s no real edge to it. There’s a freedom, but also a price to pay, in your personal life and otherwise. If you’re a searcher, you’re going to go to the dark side. You can go there if you can salvage some comedy out of it.”

The years have been hard for many Cresthill alums. The smart ones — Dice, Smirnoff, Carrey — kept their noses pretty clean from the beginning. The lucky ones — Hamilton, Maron, Binder, LaBove — got sober. Many more simply didn’t make it. Some, like Kinison, Pryor, Hicks, and Williams, died before their time. Others disappeared quietly, most of their names barely registering, even here: Prater, Sandy Baron, Adam Leslie, Fred Asparagus, Larry Beezer, Jesse Aragon, Danny Stone. Is comedy different today because of these people and this place? If Cresthill is to be feted for the careers it helped make, must it not also bear responsibility for the price it exacted?

As Pauly and Steve talk real estate, I wander out onto one of the sweeping balconies, lean against the edge, and look down toward the Sunset Strip and into L.A. It’s June and the leaves on the trees almost completely obscure the view of the Comedy Store, just a hundred or so yards down the hill. Construction cranes dot the horizon. This city will be remade over and over; Cresthill will be remodeled, again and again. What happened here — the good, the bad, the very ugly — will be forgotten and then remembered, retold as truth and fiction, until one day when the house is leveled entirely, and its stories, hopes, and dreams are ground up into a fine powder that will waft down the hill, over the Store, across the Strip, and settle over this strange, horrible, beautiful city like fairy dust.