As daylong darkness smothers the North Pole, the ice blanket that usually accompanies “polar night” is late this year to wrap itself over the Arctic Ocean.

Arctic sea ice is now 28% beneath its historic average extent, setting a record low for October. But some climate investigators say a naked northernmost ocean may also screw up weather to the south.

For the past several years, a pair of atmospheric scientists — Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University and Stephen Vavrus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison — have pushed the hypothesis that connects diminishing sea ice up north with increasingly erratic weather across the rest of the Northern Hemisphere.

But the idea that a lack of sea ice sends swirling air masses south and smacks us with horrid, frigid winters has stirred controversy in climate science. Some critics point to climate models and weather measurements that fail to match such predictions.

“What isn’t conjecture is that the strong warming trends in the Arctic will affect the circulation at least within and near the Arctic,” Vavrus told BuzzFeed news. “The big question is how far-reaching these circulation changes are and will become in the future.”

Now, with Arctic sea ice so sparse, conditions are ripe to test — and litigate — their idea that a melting North Pole means decades of extreme winter weather for the northern half of the planet.

“Jennifer Francis’ hypothesis is still controversial,” Darryn Waugh, a professor of atmospheric science at Johns Hopkins University, told BuzzFeed News. New studies from other researchers that build on the theory, including one just last month, simply “stirred the pot,” he said.

Vavrus countered that while their idea is “still a hypothesis,” it is based on “empirical and theoretical evidence.”

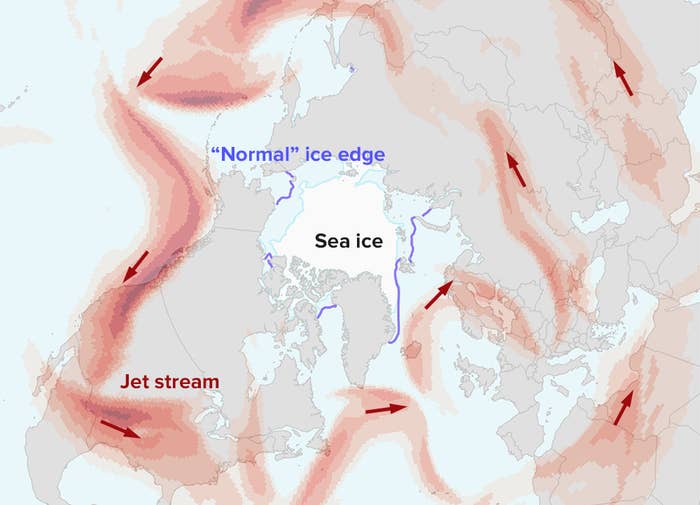

While there is overwhelming scientific consensus that heat-trapping gases released by burning fossil fuels are warming the planet (in particular at the poles), the debate shows there is still a fracas over the finer ways in which Earth’s climate will change. The idea, first outlined in a 2012 paper in Geophysical Research Letters, involves a narrow current of westerly winds that circumnavigates the top of the globe, called the polar jet stream.

According to Francis and Vavrus, when the temperature difference between the Arctic and tropics is great, the jet stream circles the Earth rapidly, hugging the northern latitudes. The winds whips by so quickly that airlines flying from New York to London will often soar into the swift current to save on fuel.

But as the Arctic warms and that temperature difference between the pole and equator decreases, they argue, those winds slow down. And like slow-moving river meandering through a desert, the diminished jet stream wobbles over the northern portions of North America, Europe and Asia.

Those waves in the jet stream funnel high-altitude surges of cold air spinning around the North Pole — best known as the polar vortex — south.

Vavrus said that what is occurring right now — a relatively balmy Arctic free of much sea ice and a bitterly cold Siberia — ”is very consistent with our hypothesis.”

But critics, such as Martin Hoerling, a meteorologist at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), doubt that the the frigid Arctic can hold such sway over the path the jet stream cuts. They argue weather systems are ultimately driven by energy — and more energy is put into the atmosphere in the tropics, where the sun shines year round, than at the chilly poles.

“There is no doubt that Arctic sea ice extent is trending downwards, with much of that multi-decadal decline in sea ice extent being due to human-induced climate change,” Hoerling told BuzzFeed News by email. “However, it remains unclear if Arctic sea ice loss is having any, detectable effect on the jet stream, at this time.”

Some powerful computer simulations of Earth’s climate, including several analyzed by Hoerling and his team, also fail to show the pattern of warm air over the Arctic and cold air over a continent.

“Changes in the position of the jet stream are very noisy, and can be hard to detect even in climate simulations,” Amy Butler, an atmospheric scientist at NOAA, told BuzzFeed News.

That jet stream puzzle is part of a wider challenge in atmospheric science: Connecting big decade-long climate projections to tomorrow's weather report.

“The community is still trying to figure out why some climate model simulations generate a warm Arctic-cold continents patterns, while others do not,” Vavrus said.

In early 2014, the continent caught in a cold snap as the jet stream meandered was North America. After record-low temperatures were set through the United States, “polar vortex” became a household term.

The idea also caught the attention of the White House.

That winter, John Holdren, President Obama’s top science adviser, appeared in a video to say “the kind of extreme cold being experienced by much of the United States as we speak, is a pattern that we can expect to see with increasing frequency as global warming continues” — essentially endorsing Francis and Vavrus’s hypothesis.

In response, a group of skeptical climate scientists penned an op-ed in the journal Science. While the idea “deserves a fair hearing”, they wrote, “to make it the centerpiece of the public discourse on global warming is inappropriate and a distraction.”

But if they are wrong, we may be in for another winter like 2014, when temperatures of 4 degrees Fahrenheit broke a 116-year-ago record in New York.

Atmospheric scientists, like Butler at NOAA, warn it is hard to predict the twists and turns the jet stream will make more than 10 days in advance.

Vavrus agreed that even if you know the jet stream will wobble in general, it is difficult to say where specifically it will kink.

“If I knew for sure,” Vavrus said, “I could be rich.”