A program that hosts armed police in local high schools will be debated Thursday at the Toronto Police Services Board meeting. Police and schools first collaborated on the controversial School Resource Officer (SRO) program in 2008. Toronto’s version of the program suffers from several challenges, especially regarding community consent, useful program data, and risks to racialized and undocumented students. Here are seven things you need to know about police in Toronto’s schools.

1. Police and schools launched Toronto’s SRO program without notice or public consultation.

In the summer of 2008, Police and school boards announced their intention to put police officers in Toronto’s schools. According to the Toronto District School Board then-director John Campbell, the program’s goal was to “enable officers to get to know students better, and for students to get to know officers better.” Neither the TDSB, its Catholic school counterpart, the TCDSB, nor the Toronto Police Services Board held public consultations on putting police in schools.

On June 24, 2008, when he announced the program, Campbell said police would not be in uniform. However on the same date, then-Toronto Police Chief Bill Blair held a separate news conference to announce that officers would indeed be armed and in uniform. "It's not my intention we'll go in and be hall monitors,” Blair said. “My officers work best in uniform.”

2. The program is part of a controversial anti-violence strategy.

Toronto’s SRO program came out of the Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy (TAVIS), a team of officers who have been widely criticized for violent and discriminatory policing. Community advocates and legal experts have criticized Toronto Police for carding, the practice of stopping and documenting civilians who are not suspected of a crime. Carding has disproportionately targeted Toronto’s racialized communities, namely its Black residents.

TAVIS officers have the highest rate of carding of all Toronto police units. These officers have faced several high-profile allegations of brutality and racial profiling against Black residents: drawing weapons on four unarmed teens, intimidating civilians who film them in public, and carding the same Black individuals dozens of times. The provincial government recently cut TAVIS funding in half, and Toronto police say they are restructuring the unit.

3. Police have never been clear about the purpose of the program

The SRO program mandate is broad and ever-expanding. Officers do everything from engaging in arrests in school hallways to coaching sports teams and lecturing in classes. It isn’t clear how the SRO’s anti-violence officers have been trained to handle these responsibilities in a school setting. Officials have often said the program’s main purpose is to build relationships between teens and police, but many subsequent justifications include stats about criminal activity in and around schools.

“We're not going to measure our success by the number of charges laid or drugs and weapons seized,” Blair said in June 2009. Five months later, he hailed the program a success by claiming fewer offences had occurred on school property.

It also isn’t clear why students who are disproportionately targeted by police in their communities would feel comfortable with the SRO program. Many community groups argue that students whose history with police has been negative are especially intimidated by the presence of armed police in their schools. They point to examples of excessive police force against Black students, such as an incident in September when two Peel Regional Police officers handcuffed a six year old Black girl by her ankles and wrists inside of a Mississauga classroom.

4. Public officials have almost no reliable stats about Toronto’s SRO program.

Toronto police have conducted two internal reviews of the SRO program, most recently in 2011. The reports are based almost exclusively on surveys to students, administrators and SRO officers themselves about perceptions of safety. The latest report states that while most students felt safe in schools, “the results of the student surveys in May 2009 and again in May 2011 found that overall student perception of safety did not improve.”

The same report tracks violent incidents in and around schools with and SRO. In the 2007 to 2008 school year — before the implementation of the SRO program — police documented 129 incidents of a serious nature in these areas, including aggravated assault, assault causing bodily harm, robbery, and weapons offences. In the 2010 to 2011 school year, police documented 120 incidents in the same areas. Police have offered no evidence linking the presence of officers in schools to criminal activity.

5. Racialized students are already facing disproportionate discipline in Toronto Schools.

Data from the Toronto District School Board, the largest board in Canada, consistently shows that Black and Indigenous students are more likely to be suspended from school. For example, in 2007 Black students made up only 12 percent of the TDSB’s population, but were involved in over 31 percent of suspensions. Most recently, Faculty of Education professor Carl James published a York University study showing that 48% of all TDSB expulsions are of Black students, despite the fact that only 13% of student enrolled at the board are Black.

TAVIS officers, who already have a history of profiling Black youth in the city, are now patrolling many of the schools with large populations of Black students. The police and TDSB have never disclosed how many interactions between police and students have resulted in arrests and criminal charges, nor have they isolated such statistics based on race.

6. Schools have a duty to protect undocumented students, but police do not

One of the most serious community concerns about the presence of police in schools is their interaction with undocumented students. Ontario’s Education Act states that children must have access to education regardless of the immigration status of their parents. The TDSB’s 2007 “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy says school staff will not ask students or families their immigration status, and will not disclose that status to immigration officials if they learn of it.

By contrast, Toronto police have explicitly rejected the “don’t tell” aspect of interactions with undocumented people. The police claim it is their duty to report information about undocumented people to the Canadian Border Services Agency. In 2011, Toronto Police announced that all SROs would begin meeting with a weekly information-sharing group that included border service officials.

Border service agents have apprehended children in Toronto schools, and have even held children in custody until their parents surrendered. During two separate incidents in 2006, border agents apprehended four children from Toronto schools.

7. Fewer than half of Toronto’s high schools have a school resource officer

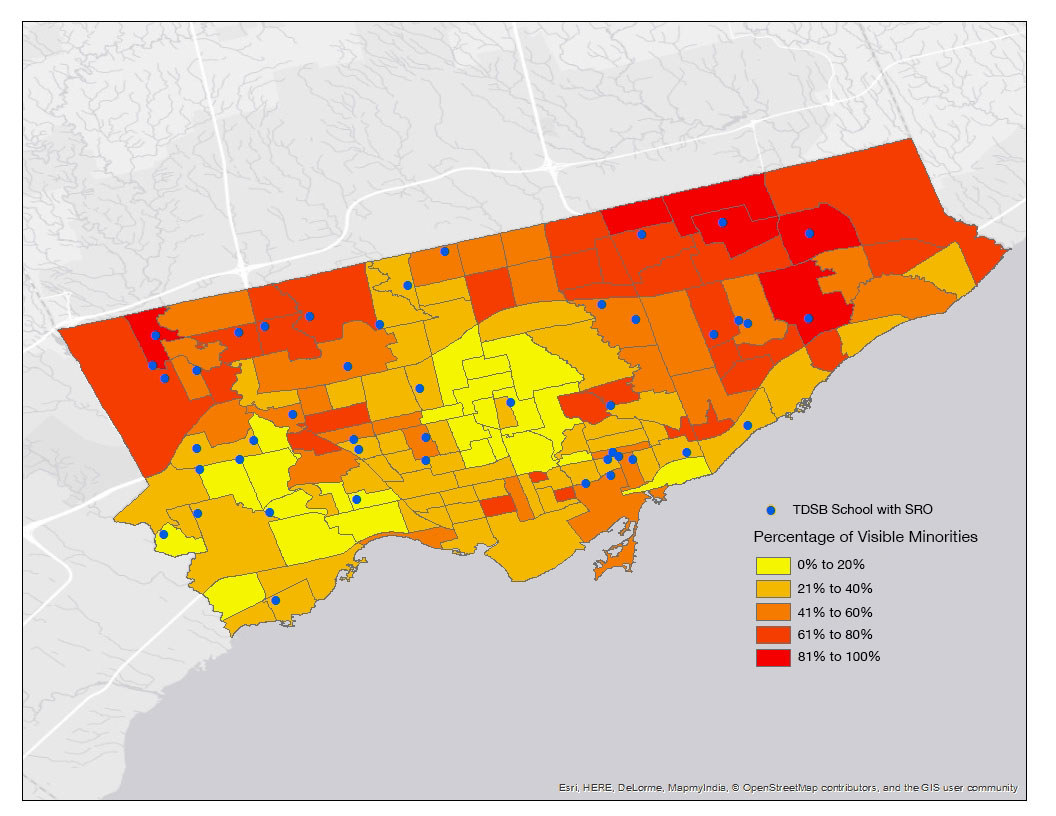

Only 45 of the TDSB’s 100 high schools employ a school resource officer. The lack of prior public consultation makes it difficult to know how the TDSB decided which schools should host the SRO program. While it is easy to assume that police would be deployed in schools with high rates of violence or misconduct, Toronto police have explicitly denied these factors affected the decision.

“The schools in Toronto were chosen, not because they had problems of violence, but because the principals and trustees were committed to making the program work,” says the 2008 Toronto Police Services annual report. A map of the 45 TDSB schools with an SRO shows high concentrations of schools in north Etobicoke and North York, areas of the city with relatively high numbers of Black residents. Since the TDSB does not publicly provide data about the racial makeup of individual schools, it is difficult to know the specific ethno-racial populations of the schools with SROs.

Desmond Cole is a freelance journalist and activist in Toronto. He detailed his personal experiences with carding in a feature for Toronto Life, and has been an outspoken critic of the practice.