Imagine a future in which small machines swarm all around us: blaring ads, doling out speeding tickets, scanning our eyes to run through facial recognition software. That's the bleak vision imagined in "The Drone Aviary," a popular video created by the London-based design group Superflux.

This drone dystopia came a little closer to reality on Wednesday, when federal aviation officials and private companies announced plans to start test-flying an undisclosed number of commercial drones.

"The unmanned aircraft industry is changing faster than any segment of the aviation industry," said Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) chief Michael Huerta from a drone industry conference in Atlanta.

At the meeting, some 8,000 attendees from 55 countries examined drone offerings from more than 600 companies. The FAA estimates up to 7,500 commercial drones may be in use by 2018, and market analysts predict the industry will be worth $5 billion by 2019.

The FAA's new partnership with three companies — CNN, drone manufacturer PrecisionHawk, and BNSF Railroad — will test drones for gathering news, surveying crops, and inspecting railroads. Agency spokesperson Les Dorr told BuzzFeed News the number of drones and where they will be tested are still being determined.

The announcement follows the February rollout of a draft of FAA rules governing commercial drone operations nationwide. These rules, if adopted, would keep commercial drones below altitudes of 500 feet and require that they remain in the line of sight of their operator on the ground, limiting their range.

But what the draft rules are missing is any mention of a hotly contested issue: privacy. And that has some experts worried about a future filled with flying peeping toms.

A federal lawsuit, proposed laws, and voluntary guidelines are all vying to set privacy standards for commercial drones, but privacy advocates fear it may be too late. Light, agile, and cheap, drones now come in insect-small sizes. And some will soon be carrying cameras with facial recognition software, according to an April Congressional Research Service report on privacy threats from drones.

"Drones are going to be in the air almost universally, most likely in a few years," Alan Butler, an attorney at the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC), told BuzzFeed News. "And they are all going to be carrying high-definition video cameras."

In April, EPIC sued the FAA over the lack of privacy protections in its proposed drone rules.

Although the agency had previously promised to consider privacy protections, its February announcement said that privacy was "beyond the scope" of its role as a safety agency.

But the public cares quite a bit. A recent Thomson Reuters poll found that 64% of U.S. adults said they wouldn't want their next-door neighbor to own a drone. Another 71% disagreed with the notion that drones should be allowed to fly over someone else's property.

Despite people's queasiness about the notion of drones watching them in their backyard, or following them down the street, that doesn't mean it's illegal.

Most states don't have limits on drone surveillance: Only a half-dozen explicitly outlaw drones peeping in people's windows. Nearly half of all states allow drones but limit law enforcement surveillance with them. Illinois, for example, requires police to destroy information gathered by drones after 30 days unless it contains information relevant to a criminal case.

But only a handful of states — such as Texas, Wisconsin, and Idaho — have privacy rules against privately owned drones. (Unlike other states with drone privacy laws, Texas allows police surveillance with drones, which the Texas Monthly called "depressingly hilarious" in a 2013 report. Some Texans have even threatened to blast drones flying overhead out of the sky.)

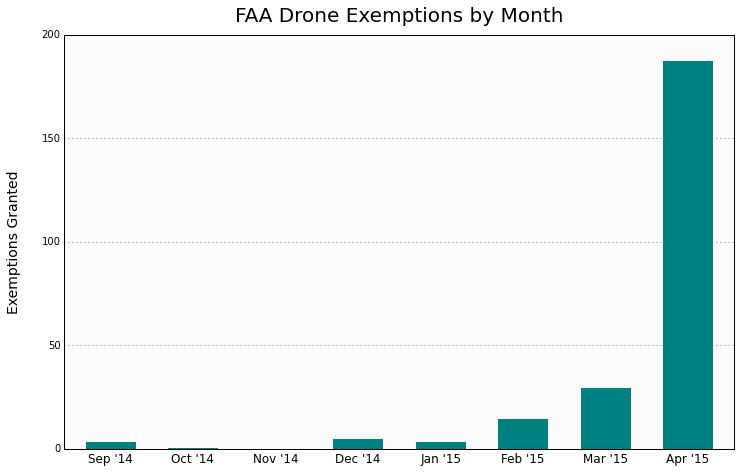

Commercial drones are less common than those owned by hobbyists or government agencies, but that's likely to change. Since the draft rules were released, FAA exemptions for commercial drones have spiked. In April, they increased more than 500%, mostly from companies involved in real estate, utilities, and movie-making. One of the April exemptions was for tests of Amazon's "Prime Air" drones, intended to someday deliver books and everything else sold by the online sales colossus to your doorstep.

Alongside the FAA lawsuit, the House and Senate are weighing bills on drone privacy.

In February, President Obama ordered the Department of Commerce to convene meetings with federal agencies, business leaders, and interest groups to make voluntary guidelines to keep drones from invading the public's privacy.

"There are a host of beneficial uses of drones that will benefit the public tremendously," Harley Geiger, an attorney at the Center for Democracy & Technology in Washington D.C., told BuzzFeed News. "But with the pace of the technology's improvement, it's important to establish privacy rules now."

Sen. Ed Markey of Massachusetts and Rep. Peter Welch of Vermont introduced a bill in 2013 that would have required businesses to issue privacy statements that listed who operated the drones, where they flew, and what drone-collected information would be sold. A bill offered by Rep. Ted Poe of Texas would go further, forbidding private drones from capturing images "in a manner highly offense to a reasonable person" where people might normally expect privacy.

On the other hand, attorneys Hank Perritt and Eliot Sprague, owners of the drone contractor Modovolate Aviation in Glencoe, Illinois, argue that peeping tom laws in states are already good enough to protect against drone intrusions.

"Lots of privacy law is on the books already," they wrote in the October issue of Business Law Today. The FAA echoed this view in its February proposed rule announcement.

But existing privacy laws don't cover drones flying 500 feet overhead, armed with a telephoto lens, and able to maneuver quietly in ways that would defy even a helicopter, Butler said. "Maybe an individual would have a remedy under a state peeping tom law for a drone camera aimed in their bedroom window, but what about drones over their backyard?"

In the U.S., a tension exists between the First Amendment, which gives people the right to take pictures from public places, and privacy laws, notes the recent Congressional Research Service report. That makes laws restricting commercial drones in public places tough to pass legal muster with courts.

A surveillance society like the "Drone Aviary" video might be the result, Butler suggests, with drones monitoring your every public — and semi-public — move. Drones would sell this surveillance information to businesses in the same way that Google and Yahoo sell internet shopping site visits to advertisers. Except the ads in the drone future would be literal pop-ups — drones appearing in your face as you walk to work, logging your reaction to sales pitches.

"The technology might have the same privacy issues that Facebook has but it will be physically moving through the city, and, because it comes in so many different forms — from imposing machines to small toys — you might even invite it into your home to play with your kids," Jon Ardern of Superflux told BuzzFeed News, by email.

Similar to the revelations of the National Security Agency tracking phone company records of millions of people nationwide, Ardern worries about privately owned drones gathering information for businesses that will end up in the hands of government agencies. The frontier in the battle for privacy, he warns, might be right over our heads.