What if the taxpayer money invented a better treatment for hepatitis, and then just gave it away?

Officials at the National Institutes of Health said that’s exactly how it’s supposed to work, when queried over public records that show the federal research agency licensed out a potential new hepatitis drug while spurning calls to require the company to set “reasonable prices” for consumers.

"It would be unfortunate," an NIH official, Anna Amar, wrote in a 2015 email, if questioning of the deal by public interest groups, "bothers the company enough to reconsider the license."

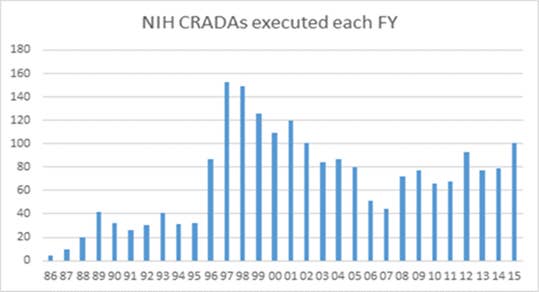

In spite of the questions, the NIH completed the licensing deal with an unknown start-up called Virotas LLC in April of 2015. It was one of about 80 such cooperative research and development agreements (CRADA’s) that the federal research agency signs every year.

“All we are doing is asking some reasonable questions about giving away the rights to a promising drug,” James Love of public interest group Knowledge Ecology International, told BuzzFeed News. “Why would you exclusively license the rights to a promising drug to an unknown firm with no track record?”

The dispute “is not the first time someone has raised questions over NIH’s method of giving exclusive rights to promising drugs,” Washington University law professor Rachel Sachs told BuzzFeed News. Since the 1980’s, health policy experts have asked why the NIH, the $31 billion federal powerhouse behind the US biomedical research system, doesn’t claw back more money from the pharmaceutical industry, where profit margins are rivaled only by banking.

“Somebody has to put pressure on them,” Sachs said. “KEI is asking the right questions here.”

In the case of chlorcyclizine, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases researcher T. Jake Liang has shown that the forty-year old drug limits hepatitis in mice. The results showed enough promise against Hepatitis C — a virus that infects about 3 million people nationwide — that NIH funded a 50-patient safety trial of the drug, which is fairly unusual for the basic research institute. (That human trial ended in September, with results still under analysis.)

The drug’s licensing last year came just as a debate over the high price of some new hepatitis drugs, notably Gilead Pharmaceuticals’ $84,000 Sovaldi, attracted the eye of Congress. A Senate Finance Committee investigation last year found that Gilead employed “a calculated scheme for pricing and marketing its Hepatitis C drug based on one primary goal, maximizing revenue, regardless of the human consequences,” according to Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon.

Given such controversies, it’s tone deaf at the least to exclusively license a new hepatitis drug to a small firm without any promise of reasonable prices for taxpayers, Love said. Public records released to his group in October show that within the NIH, questions were raised about a response to the reasonable price request, but were ultimately brushed off as beyond the mission of the research institute.

“We take it seriously, but it is not our mission to control drug prices,” NIH technology transfer chief Mark Rohrbaugh told BuzzFeed News. Previous efforts to work price restrictions into such agreements scared away firms and ended in 1995, he said. Licensing more than tripled afterwards, with one of the best-known licensing successes, a blood vessel collar coated with a chemotherapy drug that spares patients from heart bypass surgery, coming in 2004.

“The return to taxpayers is new drugs to the public,” Rohrbaugh said.

The license agreement for chlorcyclizine requires the company to pay nothing up front, committing only to pay the NIH an 8% royalty rate on any profits from the drug, with up to $150,000 going directly to the scientists who discovered it. About two dozen staff scientists collect this top number every year at NIH, although the average royalty to staffers there is only $9,000. In 2014 the NIH collected $147 million in royalties from all of its licenses, which includes medical tests and biological materials as well as drugs.

The advocacy group also requested the NIH allow outside researchers continue to look for new uses of the drug, make the research spending that Virotas does transparent to taxpayers, and allow the World Health Organization (WHO) to request a royalty-free license for NIH inventions. A WHO survey in April concluded that the newest hepatitis drugs were essentially “unaffordable” in 12 countries, such as Turkey and Egypt, where prices exceeded the average yearly income.

NIH staff vetted the firm’s ability to shepherd a promising drug through the Food and Drug Administration’s approval process, Rohrbaugh said. Fewer than 3 in 10 drugs that makes it as far as starting human volunteer testing runs this gantlet, where full blown trials can cost tens of millions of dollars apiece. The high cost of getting a drug approved means companies are unlikely to invest in licenses that come with price restrictions, he said.

Nevertheless, the US government retains “march in” rights on drugs to make them affordable, Annette Gaudino of the Treatment Action Group told BuzzFeed News by email. But those rights have only been used in wartime or after bioterrorism events. Refusal to intervene in the case of costly drugs, or to cut off unreasonable prices before they start with licenses, she said, raises questions about NIH’s rationale for licensing drugs.

“Costs are real, but price is a choice,” Gaudino said. “This gets right to the heart of what government is for: To intervene when necessary to preserve the common good, or to smooth the way for entrenched interests?”

But even if the NIH made “reasonable price” requirements a part of its drug licenses, it might not make a difference, said David Evans of Project Inform, an advocacy group for affordable HIV and hepatitis drugs.

“What we claim is the price of a drug, whether it’s $84,000 or $300,000 is almost meaningless,” he told BuzzFeed News. “Drug pricing in the US is so complicated,” he said, because in reality there isn’t really a free market for drugs, but a bewildering kaleidoscope of agreements between hospitals, insurers, clinics, and federal programs such as Medicare, all paying different discounts and rates for medicine.

Some very expensive drugs are sold at deep discount to clinics for low-income patients, Evans noted, and forcing a uniform price on them, might actually raise the price for the most vulnerable. “That makes prices a very difficult calculation for anyone to make, much less asking folks inside NIH to figure it out.”

For that reason, Love suggested that NIH get out of the drug licensing business and that such deals should be handled by the Treasury Department or Medicare accountants more interested in the bottom line. “Other countries are paying less for these drugs we paid to invent,” Love said. “There should be some limits.”