Ancient people butchered a mastodon, hammering its bones for marrow with rocks, some 130,000 years ago in California, according to a new archaeological study.

The extraordinary claim, made about a prehistoric bone bed under what is now a highway outside modern-day San Diego, would set back the age of the first human ancestors in the Americas by more than 100,000 years.

But a slew of independent fossil experts contacted by BuzzFeed News think the report, published on Wednesday in the journal Nature, is crazy.

"I have read that paper and I was astonished by it," archaeologist Donald Grayson of the University of Washington told BuzzFeed News. “I was astonished not because it is so good, but because it is so bad.”

The far more likely explanation, according to Grayson and other skeptics, is that the bones were crushed not by ancient humans, but by bulldozers carving a new highway in the 1990s.

Previous studies, based on genetic analyses and archeological evidence, suggest that the ancestors of Native Americans arrived in North America at most 25,000 years ago. They arrived by boat and on foot, crossing from Asia to Alaska over a land bridge across the Bering Strait as an Ice Age ended.

The incredibly ancient date in the new study suggests that relatives of Neanderthals — the extinct cousins of modern humans — arrived and spread across North America far earlier, which would be a revolutionary upending of conventional wisdom.

“We expect skepticism,” study lead author Steven Holen of the Center for American Paleolithic Research in Hot Springs, South Dakota, said at a briefing for reporters on the new study. “I was deeply skeptical myself.”

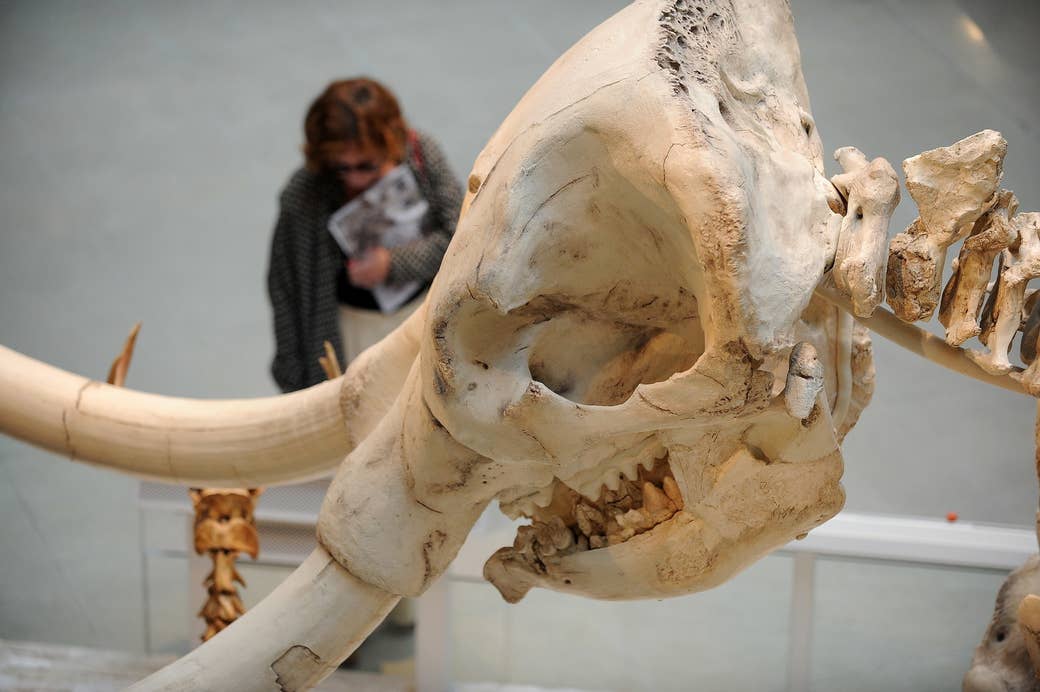

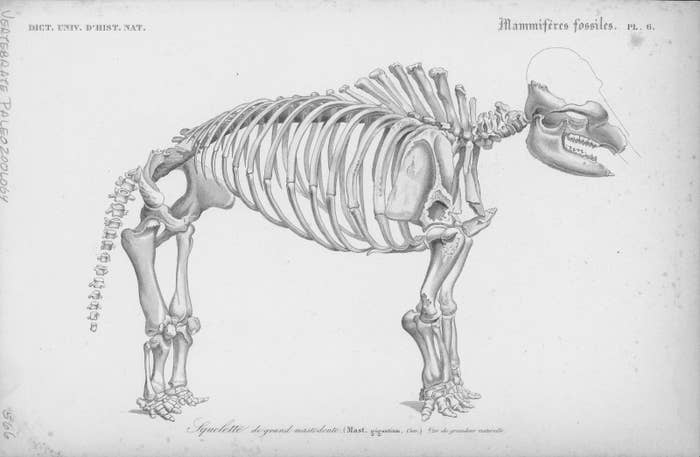

In 1992, a California Department of Transportation road-grading machine uncovered the bones of a mastodon, an ancient elephant that once roamed widely across North America, while helping to build State Route 54 outside San Diego. Paleontologist Tom Deméré of the San Diego Natural History Museum led a team that excavated the Cerutti Mastodon.

Deméré, Holen, and their colleagues now report that radioactive dating of those bone samples by US Geological Survey scientist James Paces sets their age to 130,000 years ago, plus or minus 9,000 years.

Their age is not surprising, as the site was known to be a home for ancient mastodons, a marsh full of animals near a pleasant stream. Far more remarkable is the scientists’ claim that rocks collected alongside the bones were hammers and anvils used by prehistoric humans to butcher game.

The pachyderm leg bones, molars, and tusks were found cracked in spiral patterns and apart from the rest of the skeleton. The tips of some bones were broken off. They didn’t resemble cracks from trampling, or drying out, or other natural weathering seen on the nearby fossils of a camel and a pig-like tapir, either, and they were oddly grouped together.

The team went so far as to smash the bones of a dead elephant in Tanzania with a stone hammer to replicate the fractures seen on the ancient mastodon femurs. Similar practices of smashing bones with stone hammers date back more than 1 million years ago to sites of archaic human ancestor species in Africa.

The “really compelling” evidence, Deméré said, “leads us to conclude that humans processed mastodon limb bones at the site of its burial 130,000 years ago.”

Other scientists, however, are not convinced. They point out that the study does nothing to refute a more plausible explanation: that highway equipment crushed the bones.

“The paper states that [the] bones were being exposed by a backhoe,” fossilization expert Gary Haynes of the University of Nevada Reno told BuzzFeed News by email. “These pieces of heavy equipment weigh seven to fifteen tons or more, and their weight on the sediments would have crushed bones and rocks against each other.”

When asked, Holen, the study leader, said that it “was very easy to tell the difference” between fractures made by stone hammers and those seen in bones crushed by bulldozers. He did not elaborate on how the differences manifest.

“He's pretty much dead wrong — there's no definable difference,” Haynes said. A similar fossil dispute broke out in 2015 over a 24,000 year old mammoth in Maryland, he noted, shown to be fractured by heavy equipment.

Also troubling, the “hammer” and “anvil” stones described in the paper don’t unequivocally look like tools, said Michael Waters of Texas A&M’s Center for the Study of the First Americans.

The study also runs afoul of the mounting genetic evidence, Waters added, “which indicates that the first people to reach the Americas and eventually give rise to modern Native Americans arrived no earlier than 25,000 years ago.”

Both the discovery team and its critics invoked the scientific bromide that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” as a challenge to the opposing camp.

Cracked bones and chipped stones at a fossil site might mean anything, said Grayson. “It is quite another [thing] to show that people, and people alone, could have produced those modifications.”

The study doesn’t take that step, he said, “making this a very easy claim to dismiss.”

At the end of the press briefing, Holen was asked whether he thought people would hear about his study and blame the mastodon fractures on UFOs or Bigfoot. “I expect there will be some extraordinary claims,” he replied, “not just by skeptics, but others.”