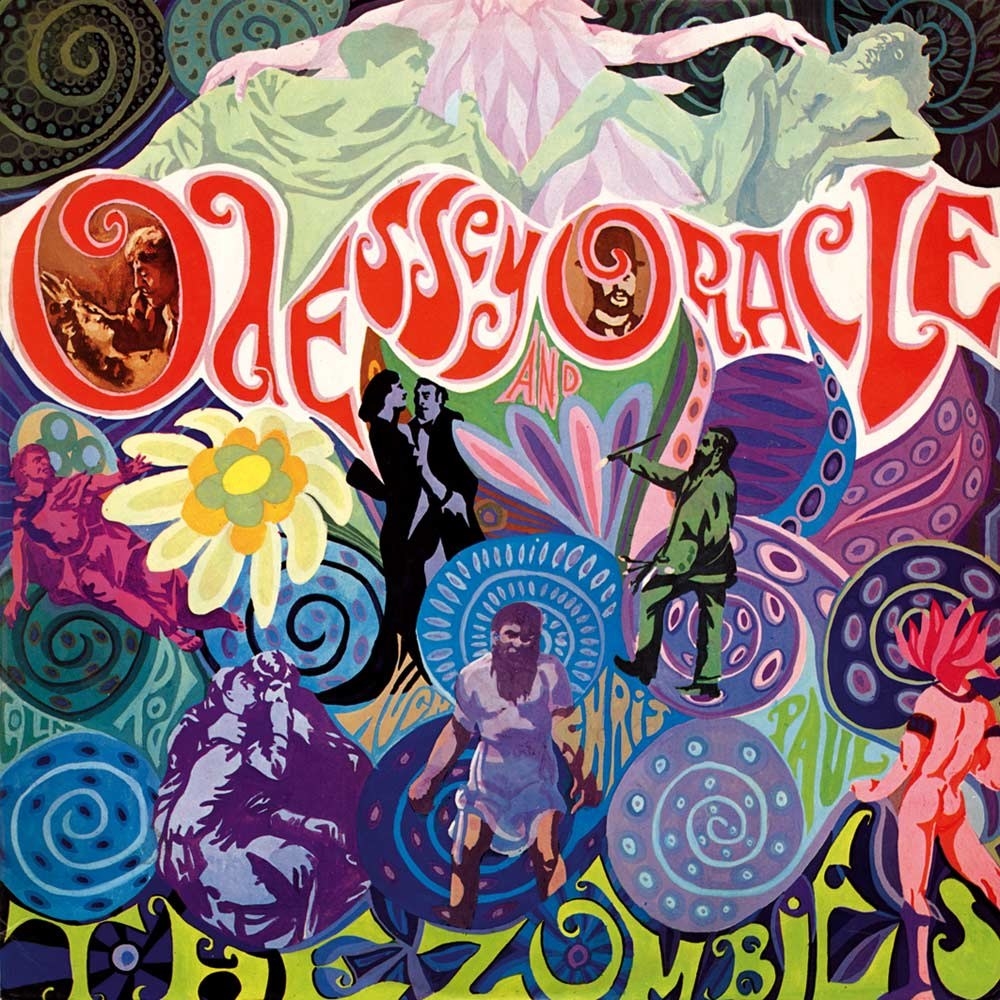

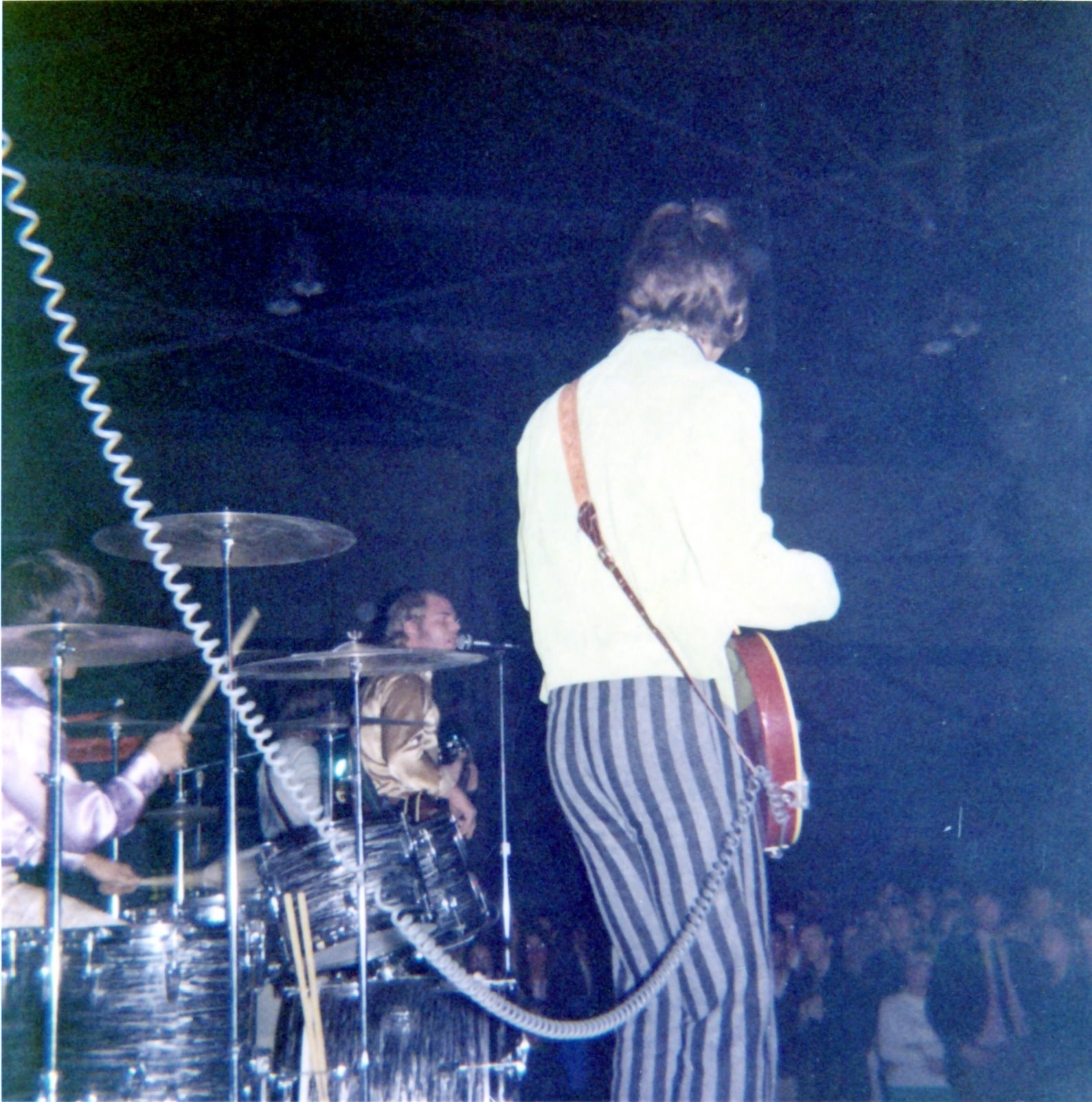

Chris White shakes his head and laughs when I show him the first photo. At 73, the bassist and songwriter for the reunited British psych-rock band the Zombies looks like a cool grandpa in black pants, blue dress shirt, and polar fleece vest — a sharp contrast from his septuagenarian bandmates who still sport leather jackets and tight pants. He adjusts his glasses and studies the image of four flamboyantly dressed young men taken in 1969. We are backstage at the Saban Theatre in Beverly Hills last October and after this brief intermission, White will join the rest of the band onstage to play the band’s cult classic 1967 album Odessey and Oracle in its entirety.

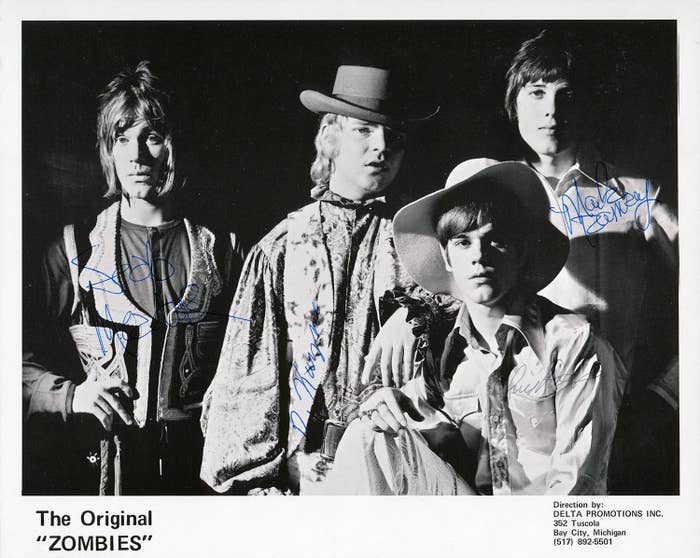

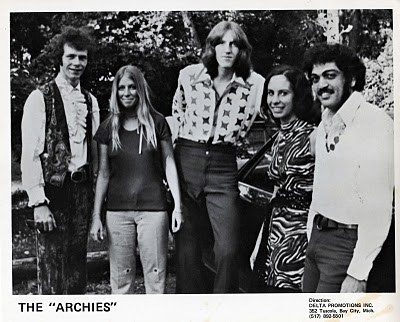

I pull up another grainy photo from 1969 on my laptop: a traditional black and white press photo for the Original "Zombies" (in conspicuous scare quotes), autographed. There are only four guys pictured despite the fact that the Zombies were a five-piece. I inform White that the two young men wearing cowboy hats are Dusty Hill and Frank Beard from the legendary Texas blues-rock band ZZ Top, although the names D. Cruz and Chris Page are scrawled over them. The real Zombies would have never worn cowboy hats.

The Zombies quietly disbanded when Odessey and Oracle failed to make the charts. Nobody even saw fit to correct the unintentionally misspelled “Odessey” on the record’s cover, viewed in hindsight as typical psychedelic-era wordplay. Almost two years after their breakup, after little fanfare and two failed singles, the band’s U.S. label, Date Records, decided to release the track “Time of the Season” as a last-ditch effort; the song went to No. 3 on the Billboard chart and the Zombies were suddenly in demand.

The Zombies, unaware of their stateside success — this was possible in 1969 — had already moved on to new musical projects or day jobs. This vacuum meant anyone could tour the United States pretending to be the Zombies, even a four-piece blues band from Dallas. As the Beatles and Stones went from garage and blues rock beginnings to more adventurous music, the Zombies took their early, more raucous hits (“She’s Not There,” “Tell Her No”) and refined them. But replicating a refined sound was hardly the priority.

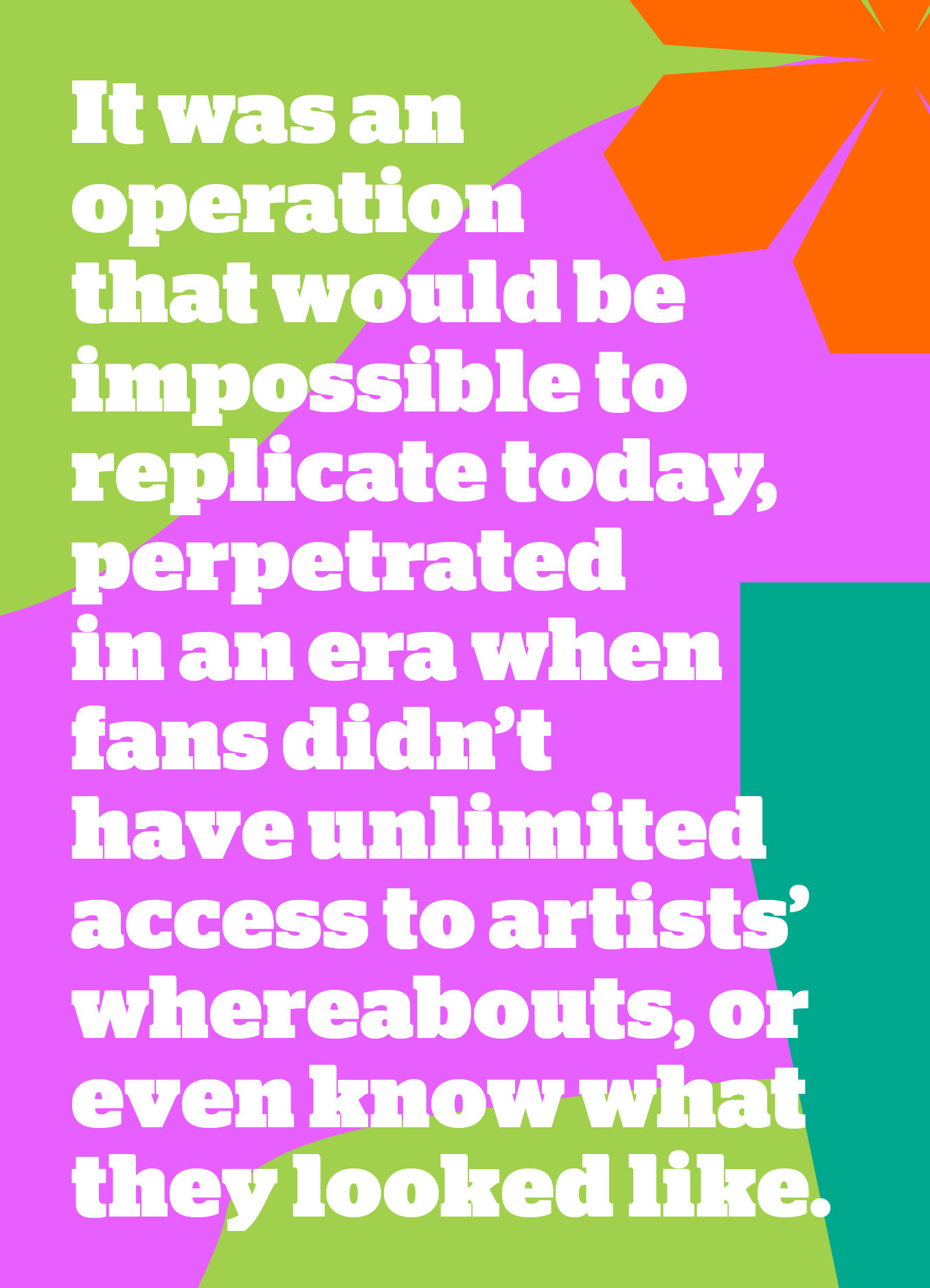

There were in fact two different bands touring the United States in 1969 calling themselves the Zombies. Both impostor groups were managed by the same company, Delta Promotions, the owners of which insisted they’d legally acquired the songs of the Zombies and other bands. It was an operation that would be impossible to attempt today, perpetrated in an era when fans didn’t have unlimited access to artists' whereabouts, or, in some cases, even know what they looked like.

In the history of the American popular music, artists have often been seen as interchangeable by the industry that promotes and distributes them. In the doo-wop era, if a member of a popular group pushed back against a manager or label boss, they were simply sent packing, with a new, more compliant candidate brought in to replace them. Over the course of their existence, the Drifters have had somewhere around 60 members.

It was in this climate that Delta Promotions took this exploitation to a new extreme, figuring out a way to tour and sell “the Zombies” and other bands without those bands or their fans even realizing. As the British Invasion spurred rock's cultural explosion in the '60s, there simply weren't yet enough of these upstart bands touring North America to meet the demand. So they made some up.

Nearly 50 years later, what happened with the Zombies is now more myth than scandal, hazy details further lost to history, with many of its principal players gone or forgotten. But, in terms of sheer audacity and brazenness, it’s a story that’s still hard to top.

Before he joined Hill and Beard in the Texas band that passed itself off as the Zombies, Mark Ramsey was 18 years old and living on the outskirts of Dallas. He was good-looking, he had a sweet girlfriend named Vicki, and he loved playing guitar. During his senior year of high school, a Texas blues band called the Gentlemen came to play a school-sponsored rock concert, featuring neighborhood hotshot guitarist — and future fellow fake Zombie — Sebastian “Seab” Meador. The Gentlemen had scored a minor hit with their single "It’s a Cry’n Shame" in 1966 when Meador was only 16, and Ramsey couldn’t pass up the opportunity to introduce himself.

Ramsey remembers meeting Frank Beard later at a spot in Fort Worth called Pizza Inn, where they became fast friends. Beard knew everyone in the Dallas music scene and was noted for playing a drum kit with two bass drums, the mark of a badass drummer in 1969. Beard was already friends with Dusty Hill, and he took Ramsey to see Hill’s band American Blues.

It wasn’t long after that that Ramsey got the call to join the fake Zombies, which at the time featured Beard, Hill, and Meador. He isn’t exactly sure how the offer came about, and is unsurprisingly fuzzy about some of the details of the era. “The ‘60s were consumed with the fascination of experimentation,” he says now, wryly. “Frank was the one who approached me."

Frank Beard and Dusty Hill declined to be interviewed for this story, but Hill did respond to fact-checking questions by email via his manager — the first time either ZZ Top member has ever publicly acknowledged involvement in the Zombies scheme. Like Ramsey, however, Hill said he couldn’t recall how the band got started: "It was the '60s, man." Ramsey believes they were connected with Delta Promotions through someone Meador met on tour with the Gentlemen in Florida. The players were told that the operation was perfectly legal, according to Ramsey.

“As far as the Zombies, I was told they didn't exist," he recalls. "That they were only a studio sound. I was just excited and flattered. I'd only been playing for a few years and the other guys were pro-level at that point. I didn't look at it as anything more than a chance to have some fun, hang out with some cool guys, learn some songs, go somewhere outside of this Hillbillyville, and earn a little money."

As a warm-up for the Zombies tour, Delta Promotions asked the Texas Zombies to go on a short tour as a different, less successful, also recently disbanded group called the Rose Garden, a Los Angeles folk-rock quintet who had a Top 20 hit in 1967 with the song “Next Plane to London.” Ramsey remembers it being the only Rose Garden song they bothered learning; the rest of their set was blues. To everyone’s satisfaction, a small run of shows in the South went off without incident.

Audiences were so starved for live music that no one confronted the fake Rose Garden despite the fact that the real Rose Garden had a female lead singer, Diana DeRose. (DeRose hailed from West Virginia, but reportedly told people she was from Blackpool, England; fact-checking was not a priority in this era.) “People did start asking where the girl was but we did OK,” recalls Hill. The lack of repercussions emboldened them when they decided to tour without a keyboard player for their Zombies gigs. Ramsey remembers Beard telling people their keyboardist had gotten busted in Dallas and was stuck in jail.

After their Rose Garden tour, Ramsey, Meador, Hill, and Beard headed to Michigan to meet with the Delta Promotions team, get photos taken, and start their run as the Zombies. They were told to use their own clothes for the shoot — that’s where the cowboy hats came in.

"You'll notice both Dusty and Frank are using stage names," Ramsey says of the signed promo shot. "So it's almost like they knew something was wrong here. Seab signed his real name like me, probably because, like me, he didn't think we were doing anything wrong."

The building that housed the Delta Promotions offices still stands, just as it did in 1969, alone on a dusty stretch of Tuscola Road on the outskirts of Bay City, Michigan. From this secluded spot, local businessman Bill Kehoe and his partner Jim Atherton managed Question Mark and the Mysterians and a number of smaller local bands. Tom Hocott was the first employee of Delta Promotions. He now lives in Grand Rapids where he plays music and lives a quiet life. He reluctantly agreed to meet me at a Chili’s outside of town to discuss his time with Delta Promotions. When we sit down to eat, he places a manila envelope on the table. He keeps his hand on it while telling me the story of his involvement with the fake Zombies.

Before the decline of the major label system and the rise of the internet and social media, enterprising and less than scrupulous businessmen ran the industry with relative impunity, with artists serving primarily as commodities to be exploited. Famously, Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker pocketed anywhere from 25 to 50% of the star’s gross income for the duration of his career. Allen Klein, who managed the Rolling Stones after the release of “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” in 1965, promptly signed the band’s publishing rights to his own company ABKCO, resulting in a string of lawsuits spanning decades. If this treatment was the norm for the era's biggest stars, it's not hard to imagine how lesser lights would fare.

Delta promoted its groups and put on shows at Band Canyon, the venue Kehoe owned in Bay City. “I remember it starting out pretty legitimate,” Hocott says. “Then Kehoe and Atherton started telling me that they’d acquired the rights to the music and the names of these bigger bands like the Zombies and the Animals … I knew it was probably bullshit but I guess I didn’t care. I was happy to be working in music.” Hocott is the only Delta Promotions employee who would talk about the operation. Bill Kehoe died in 1990. As for Kehoe’s partner Jim Atherton, Tom Hocott heard a rumor he’d been shot in Grand Rapids a few years after Delta Promotions folded but there is no record of this occurring. Attempts to locate Atherton were unsuccessful.

Delta Promotions was the first to notice the Zombies void in America. The plan was simple: Find competent musicians, convince them Delta was on the level, get them to a reasonable point of Zombies-like ability, and send them on the road. Once the prep was completed, they’d send the bands on tour while Delta took a healthy slice of the profits. Bay City, quiet and isolated from any prominent record labels or magazines, proved the perfect spot to operate. Delta could work in relative obscurity, sending its fake bands into metropolitan areas to absorb the risks while Kehoe and Atherton and Hocott laid low. As for how the Texas Zombies got on Delta’s radar, Hocott remembers Atherton having connections in Florida. He also recalls meeting someone who matches the description of Seab Meador months before the Texas Zombies tour.

“This guy,” he says, pointing at a photo I show him of Seab Meador. “He came through Michigan first. I remember that haircut and he played a red Gibson Flying V guitar.” In one of the photos Ramsey handed me, Seab Meador is seen playing a red Flying V.

Delta had a history of shady business ventures. Early in Hocott’s employment he, along with a few other employees (including Jim Atherton), was busted for selling drugs out of the Delta offices. The police also found firearms on the premises. Hocott spent a few nights in jail. He believes his boss, Bill Kehoe, pulled strings with his friends in local government to get him out. The charges against all of them were dropped.

June 22, 1969, was a rough night for the Original "Zombies." According to the Saginaw News, the band were “especially disappointing” and “the crowd began to leave during their fourth tune.” The newspaper also says the band didn’t sound like they did back when they were selling millions of records. The change in sound is attributed to “a complete transition of band members…except the bass player.”

The other bands on the bill didn’t fare much better. The shambolic and chaotic nature of the Michigan rock 'n' roll scene was on full display that night. Openers Dick Rabbit threw copies of their new single into the crowd. According to the review, “Several of the records were thrown back” once the band started playing. Headliners and local heroes Question Mark and the Mysterians fared no better. They performed the entire first song before realizing the mics weren’t working. The one song everyone in the crowd came to see, “96 Tears,” could not be performed because the band’s organist had quit a week earlier and they couldn’t find anyone to fill in. According to the review, “When their 40-minute set was finally finished…there was no applause — nothing but dead silence.”

This account makes it easy to understand how a group of guys from Texas could breeze into a town calling themselves the Zombies, play a show, and then leave without incident. Locally produced rock 'n' roll shows were often a disorganized mess. Most local reviews from the era mention bad sound, shoddy playing, and unimpressed audiences. The fake Zombies fared no worse than the real Question Mark and the Mysterians, who were themselves something of an off-brand version of their original incarnation by 1969, featuring only one original member. Even the real bands felt like impostors.

“I think the reviewer must have been drunk," Mark Ramsey says of the Saginaw show. "I don’t remember anyone walking out. Were we perfect? No, and we weren’t the Zombies. We were a blues rock band from Texas, a band with plenty of good looks, better than the original Zombies.”

They played small clubs in Michigan and Wisconsin and went up into Canada, where they appeared on TV and played a gig in a prison — it’s there where Ramsey’s story begins to differ from that of Tom Hocott. “I have a feeling that they kinda divided from Delta promotions and did their own thing," Hocott says. "Can you imagine? I never would have sent them to prison!”

"I can’t remember how we got the gig," remembers Dusty Hill, "but I remember a stage hand, an inmate, who was joking about escaping in my guitar case.”

Delta kept its operation simple. Hocott says the concert promoters in most cities knew they were getting fake versions of real bands. They operated as independent entities, each taking a huge percentage of the money earned. The bands had little recourse in asking for more. Ramsey remembers earning about $200 a week. As for the fans who were getting swindled, Hocott says, “When they were told, ‘Here’s the Zombies,’ they bought it. Even the strange parts, like the fact that they were touring without a keyboardist.” Fans left disappointed and the bands left town as quickly as possible. The less remembered, the better. "Then these guys came along."

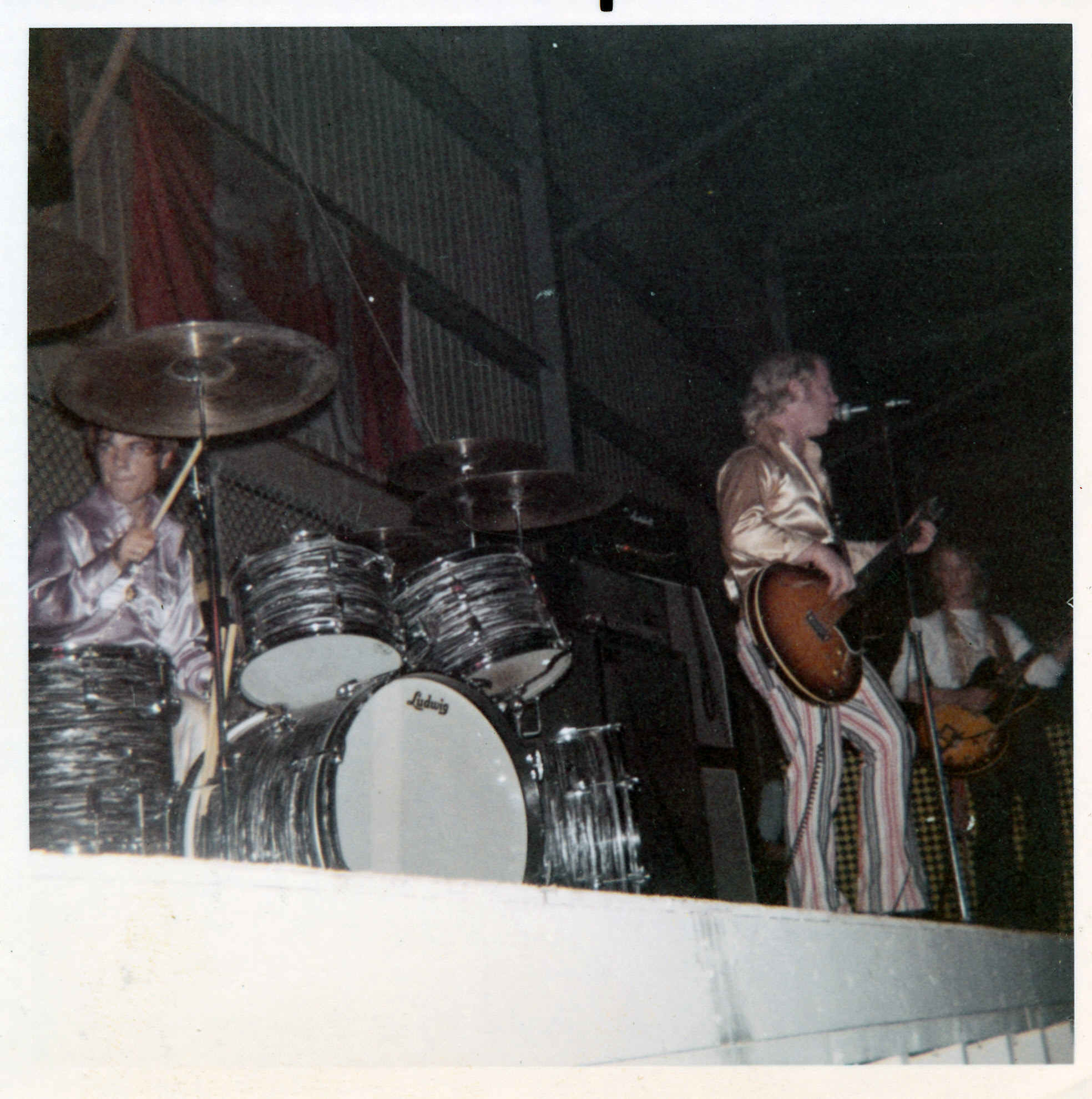

Hocott opens the manila envelope and hands me a stack of photos of the other fake Zombies. They are dressed in muted, vaguely psychedelic garb, ascots and striped trousers. It’s closer to the look of the actual Zombies. The second fake Zombies were a five-piece from nearby Marquette, Michigan, right in Delta’s backyard.

The band was made up of members of the Excels, a Beach Boys–inspired band who would’ve likely played at Kehoe’s club, Band Canyon. They were a regional success during the mid '60s, recording a number of singles that charted on local radio. Hocott’s photos of the Michigan Zombies suggest that several of the Excels took part in the fake Zombies; he claims he does not recall any of their names. Multiple phone calls and messages to the surviving members of the Excels were not returned.

“They were so damn good," Hocott says. "They were the perfect Zombies. If you heard them play ‘Time of the Season’ you couldn’t tell the difference.” They were so good that Delta Promotions felt comfortable increasing the size and scale of the tours. “They had a tour bus,” Hocott says. “We sent a road manager out with them.”

Hocott reaches into the envelope and pulls out a second photo. It’s another press shot. I recognize it immediately. The cowboy hats are hard to mistake.

In a Rolling Stone article from December 13, 1969, titled "The ‘Zombies' Are A Stiff," Chris White chastises the impostors for “taking money from our fans and dragging down our reputation.” He goes on to recount an incident where the fakes “had the cheek to phone up [the label] in Dallas and ask for $1,000 in publicity money.”

Dusty Hill refutes this accusation: “We were just making whatever we were making and happy to get some money to get another band together, but we didn’t do that.”

There is no information in the article about the fake band members themselves but there is mention of a specific show on October 21, in Los Angeles at the Whiskey A Go-Go. As White remembers it now, friends of original Zombie Paul Atkinson went to this gig and managed to get the impostors on tape. “He had someone go along with a tape recorder as a journalist. They had a guitar player calling himself [actual Zombies drummer Hugh] Grundy. They asked him why he was now out front as the singer and he said, in a Northern England accent, ‘Well, the boys wanted me out front and I’m the only original member.’ Then the interviewer said, 'Didn’t you used to be 5’10”?' This guy was 5’6”. We had it on tape but I don’t know where it’s gone to now."

In most cases, Delta Promotions would claim its bands had one original member, as it did with the Saginaw News. When Rolling Stone contacted Bill Kehoe for comment in December 1969, he claimed that the “American Zombies” formed after “the lead singer of the Zombies was killed, and two other guys left.” He goes on to brazenly inform the magazine that the current Zombies are the second incarnation he’s created. “They’re not a new group. They used to be the Excels.”

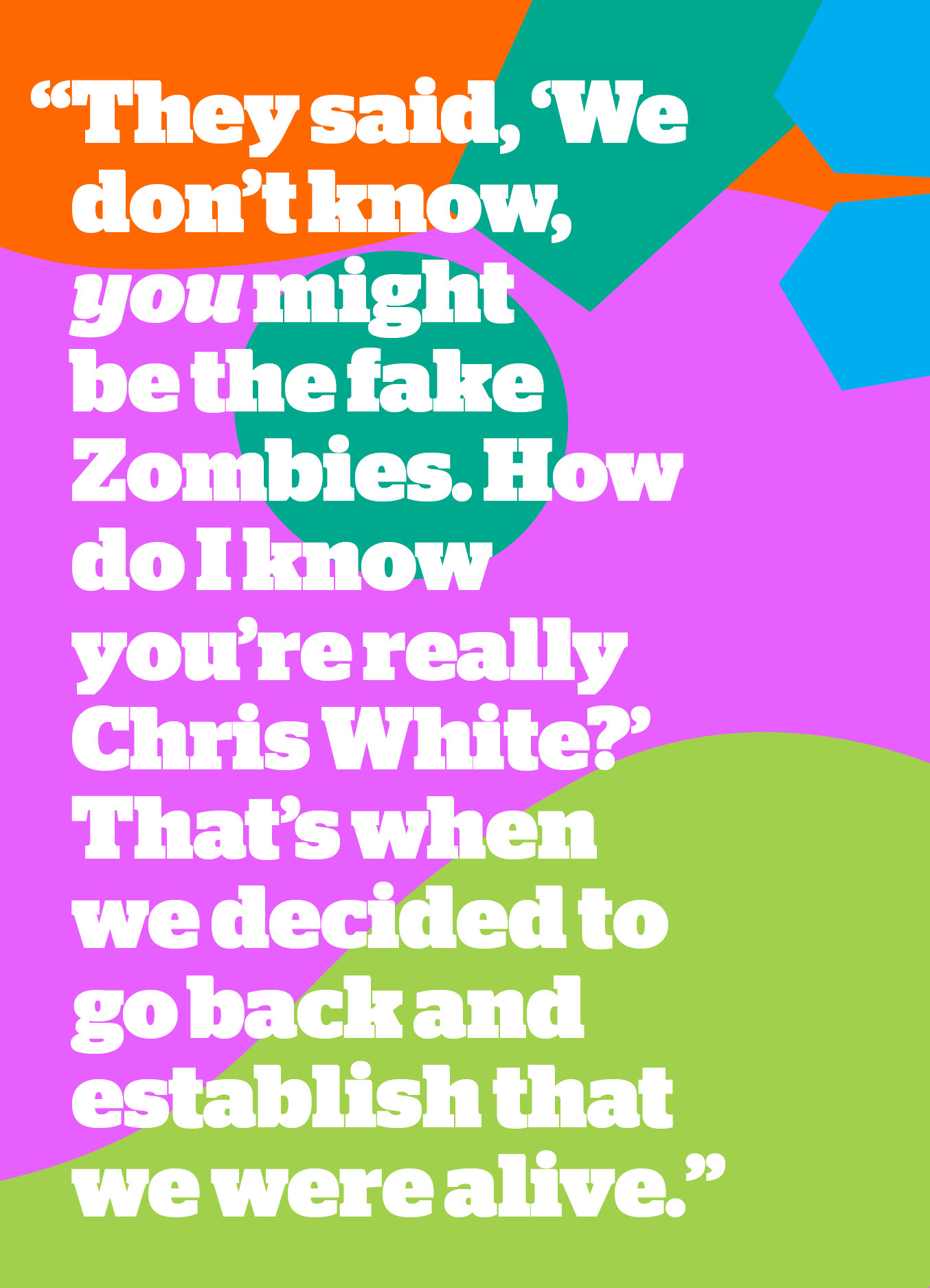

Chris White recounts a meeting at his label, CBS Records, in New York. Promoters at a radio station noticed the Zombies were coming to town and wanted to talk to him. “I said, ‘Well, it’s not the real Zombies, we are here.' They said, ‘We don’t know, you might be the fake Zombies. How do I know you’re really Chris White?’ That’s when we decided to go back and do the third album and establish that we were alive.”

Reforming the band wasn’t something anyone was eager to do. Rod Argent and Chris White had a new band, Argent, while singer Colin Blunstone had started his solo career. But the existence of the fake Zombies provided a strong incentive. If a fan went to see the impostor band and left disappointed, it’s unlikely they’d purchase a record or buy a ticket to a future concert by one of the real band’s members. But despite their efforts, they abandoned the recording and wouldn’t release the proof-of-life album (RIP) until 2010.

Backlash from the bands whose identities it had effectively stolen ballooned to the point where Delta could no longer keep up its charade. The beginning of the end came when a fake version of the Animals created by Delta were confronted at a performance by the founder of the actual Animals, Eric Burdon. According to an article in the May 28, 1970, issue of Rolling Stone by Ben Fong-Torres, Burdon had shown up to the show with a baseball bat. Tom Hocott remembers getting a phone call from one of the fake Animals recounting this same story. “Eric Burdon and a bunch of bikers chased them around and threatened them,” he says. Burdon was contacted for this story; his wife Marianna responded with an email saying, “I asked Eric if he has any recollections of the incident you mentioned, but he doesn't really.”

The Rolling Stone article also mentions the existence of another fraudulent Delta Promotions group, and the one that would finally lead to the company’s undoing: the Archies. The Archies were a cartoon — not the way Keith Richards or Gene Simmons are cartoons but actual cartoons. They were a fictitious band comprising characters from the Archie Comics universe, an entity controlled by Don Kirshner, who also created the Monkees. Kirshner was an excellent producer and shrewd businessman. He took the popularity of the comic book characters and turned it into hit records like “Sugar Sugar” and “Jingle Jangle.” Hocott believes the fake Archies consisted of members of a folk group called the Bluesberry Jam.

While it might seem like this would be the easiest con to pull off for Delta, since there were no real Archies at all, that was not the case. Unlike the disbanded rock bands and their labels, Kirshner Productions was a well-oiled machine ready to take down any dubious claims to the music of its properties. “We’ve heard about this group and our lawyers are taking action,” Kirshner, who died in 2011, told Rolling Stone.

Kirshner’s words in the magazine must have given Bill Kehoe cause for concern. Just two weeks after the article ran, a headline appeared in the Bay City Times: "Band Promoter Quits, Blasts DJs, Mafia." The article was Kehoe’s attempt to get out in front of the controversy. He expressed disgust and exhaustion with the music business, without mentioning the lawsuits (and baseball bats) encroaching on the Delta operation. “We never represented to anyone that these were the same groups who made the records," Kehoe claimed. This is in direct opposition to statements from disc jockeys and promoters in the Rolling Stone story who say Delta provided phony affidavits claiming the bands featured original members. One DJ says such documents were promised by Delta but never delivered.

Later in the Bay City Times article, Kehoe turned his ire to the bands themselves. “In two years I lost $20,000 in the business. One of the groups wrecked a bus we bought for them and some didn’t pay us back money we advanced them,” he said, adding that his pet peeve is “groups who cheat us every chance they can.”

When I mention Kehoe’s claim, Ramsey responds, “I was making $200 a week and it wasn’t like we’d play a night and then get a few days off. They had us playing shows every single night." After closing up shop, Kehoe poured his time into his legitimate business dealings, including his music venue Band Canyon and, later, an engineering company. His obituary does not mention his time working in the music business. “It just didn’t work out,” he said. “When all you do is lose money…there’s not much to do but quit. But regardless of what others would have you think, at least I can quit knowing I stayed honest.”

With Delta Promotions dissolved under pressure from outside, the bands on the Delta roster headed back home. The Texas Zombies returned to Dallas where they ditched their Zombies past and returned to their normal lives. Seab Meador was in the Werewolves, who made two albums for RCA records; he died of a brain tumor on January 24, 1980. Mark Ramsey decided to go to college, studying to become a teacher, but kept his chops up in case Seab, Dusty, or Frank ever needed a guitarist. When Meador died, Ramsey gave up on the rock 'n' roll dream. “It just changed for me. He was sweet and kind. I just kinda stopped wanting that life."

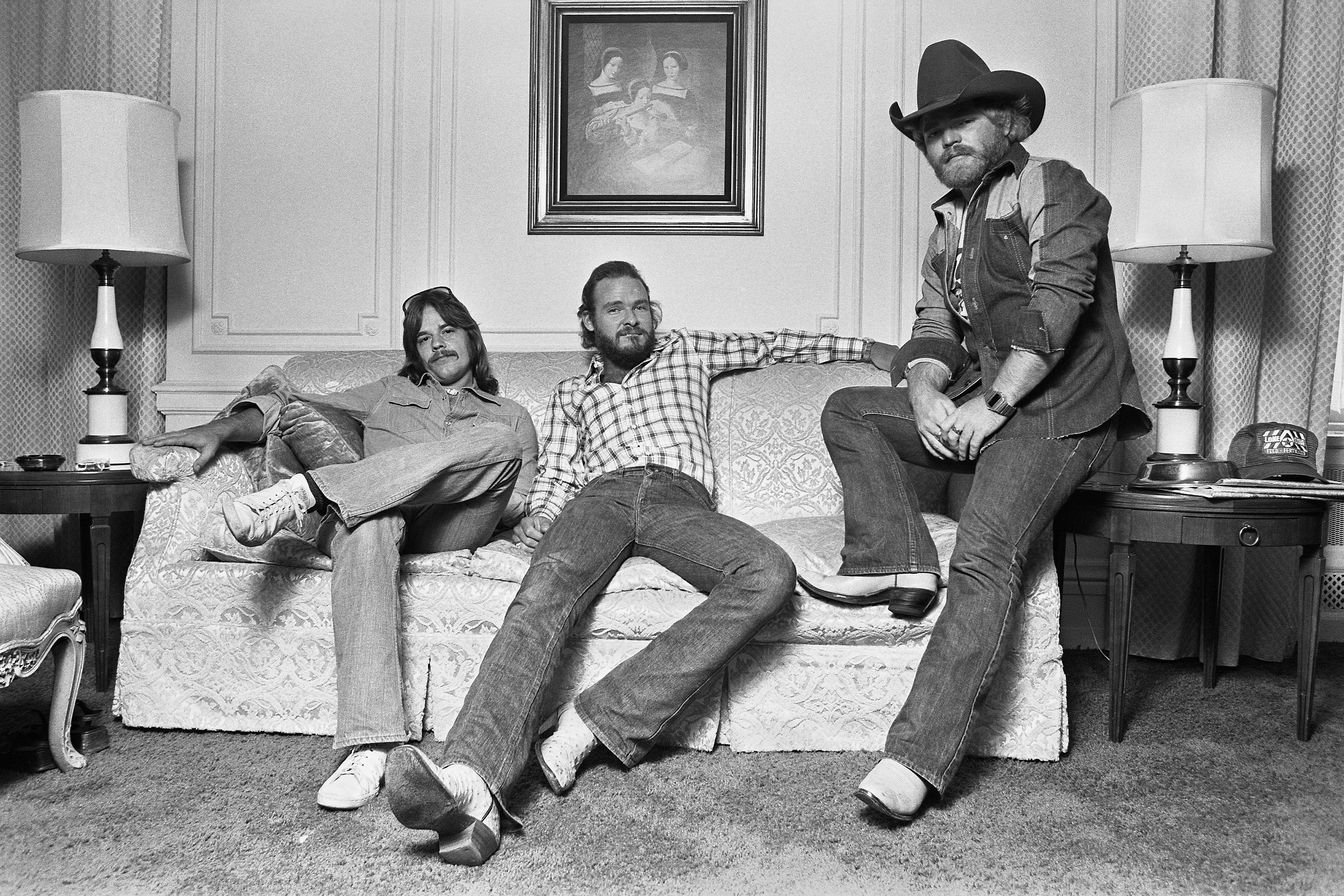

Hill and Beard formed ZZ Top with guitarist and singer Billy Gibbons; they released their first album in 1970 and have since sold around 60 million albums worldwide. Ramsey crossed paths with them a few times over the years that followed before all communication eventually stopped.

About 10 years ago, Tom Hocott claims he tried to talk to Dusty Hill backstage at a ZZ Top gig in Grand Rapids. He hoped for a brief audience with Hill — one conversation to fill in the gaps that still remained for him in the story, to congratulate Hill on his success, and to reminisce about the strange history that they both shared. But Hill turned Hocott away. “He acted like he didn’t even remember,” Hocott recalls. ("I'll say it again," Hill responds. "It was the '60s.")

Backstage at the Saban Theatre, I ask Chris White if, 46 years later, any hard feelings remain. “No, not at all," he says with a laugh. "There’s no bitterness there.” •

CORRECTION

Hugh Grundy was the original drummer for the Zombies. An earlier version of this story misstated his role in the band.