When it comes to Facebook’s effort to stop the flow of misinformation on its platform, the labels can be misleading — and the project appears to be more about perfecting the company's algorithms than providing a “Good Housekeeping” stamp of approval for readers.

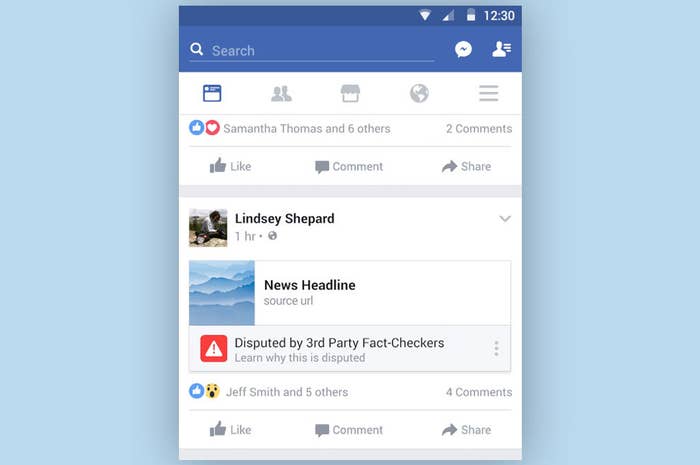

Almost exactly nine months ago, the company announced it would add a “disputed by third party fact-checkers” label to links in the News Feed that external fact checkers deemed completely false. Since then, the label has been a major focus of reporting and research. “Tagging fake news on Facebook doesn't work, study says,” read the headline on a Politico story about a draft research paper. (Facebook questioned the study’s methodology and the validity of its findings.)

But here’s the hidden truth people keep missing: the public’s reaction to the disputed label is largely irrelevant to stopping the spread of misinformation.

One reason is that any link rated false by third party checkers automatically has its reach reduced on Facebook. People can share it all they want but the platform prevents it from going viral as a result of an algorithmic push.

“The [disputed label] is almost more valuable in terms of reduced reach than in terms of consequences of users understanding of the individual item,” Alexios Mantzarlis, director of the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), told BuzzFeed News.

The second, less obvious reason why the label isn’t the most important piece of Facebook’s initiative is that these fact checked links are being added to what is fast becoming the world’s biggest and most up to date database of false stories. As with everything about Facebook, it’s the data and the algorithms that matter most.

With each new debunked story, the company gathers more data it can use to train its algorithms to make better decisions about which content to surface in the News Feed. This means the fact checkers are in effect working as content raters for Facebook in order to help train machines. Not surprisingly, this isn’t what motivates the fact checkers to do their work.

“I don't want to sound like a Neanderthal but I'm not really focusing on it,” Aaron Sharockman, the executive director of PolitiFact, told BuzzFeed News. “For us, our biggest priorities are to make the tools we use to spot and fact check fake news as efficient as possible so we can cover as much ground and have an impact.”

As the checkers go about their important work, Facebook is now beginning to use their data to roll out new initiatives. Last month it announced that pages which repeatedly share false news stories will be blocked from using ad tools on the platform. Facebook is identifying these pages using the stories declared false by its fact checking partners. Thanks to that data, the company can now easily track if a page keeps sharing false stories, and automatically block that page from promoting itself with boosted posts or other types of ads. This is a powerful deterrent.

But unlike a disputed label in the News Feed, an ad product tweak based on a database of objectively false stories isn’t something that users see, and it’s not something a researcher can analyze. As with so much of Facebook’s data, it’s not accessible those outside the company. So yes, this is yet another example of data-rich Facebook getting even richer. (At least Facebook is now paying its fact checking partners for their work.)

This type of database is time-consuming and expensive to maintain. Normally, researchers have to secure grants and train people to evaluate and classify content. Facebook’s partnership with the likes of PolitiFact and Snopes means the company has some of the best fact checkers in the business identifying completely false stories, thereby providing a constant stream of high quality data.

I know from personal experience how hard it is to generate reliable data in this area. In 2014 I led a research project that tracked rumors being reported by news websites and logged whether they were true, false, or unverified. At the end of the project, a research assistant and I had gathered more than 100 rumors and over 1,500 news articles citing them into a database. It was an almost full time job for me for several months to get that data.

Similar projects also needed significant human effort to classify stories, tweets, images or other kinds of content. For example, an EU-funded project created a corpus of several hundred real and fake images shared on Twitter during Hurricane Sandy, the Boston Marathon bombings, and other news events. Another rumor-analysis project produced a set of over 300 manually-annotated Twitter conversations, as well as a dataset of 5,000 annotated tweets.

Quality datasets of this nature are hard to come by — and I’m not aware of any that are being maintained on an ongoing basis like the one Facebook is building. That’s why years later I still receive requests from academics to use my project’s data. (In addition to the fact checkers, Facebook also gets the data generated when users report a link as false.)

With the fact checkers, Facebook has found a way to create a reliable source of expertly-annotated data it can mine to create smarter artificial intelligence. Along with spotting completely false stories, the data may also prove useful in helping the platform identify common characteristics of low-quality websites. This is good news, and ultimately far more impactful than a label being shown to users. That’s not to suggest the label isn’t important — at the very least it reminds hoaxsters they will be publicly called out, in addition to having their reach killed and Facebook’s ad tools turned off. The label should exist, and it should work.

But the reality is that on a platform with over 2 billion monthly active users, human fact checkers and labels on links only go so far. Mantzarlis said the combination of humans and artificial intelligence is ultimately the only way to address the problem at the scale Facebook operates.

“I think Facebook understands that a combination of artificial intelligence and human fact checkers is probably a winning one,” he said.

He also said this means Facebook is likely to keep working with fact checkers over the long term.

“We’re not in a place where they’re just using the human [checkers as] experiments and will then cut them all off suddenly,” he said.

Mantzarlis was referring to Facebook’s decision last year to get rid of the human curators who worked on its Trending product in favor of using an algorithm-driven approach. The initial result of that decision was that the Trending product promoted several false stories to potentially millions of users.

It seems Facebook learned its lesson: keep the humans and display their work publicly, but most importantly make sure you’re feeding the machines.