Union membership hit an all-time low in 2016, as numbers dropped for private and public sector unions for the first time in four years. Just 10.7% of the American workforce — and only 6.4% of private sector employees — are now unionized, according to government data released on Thursday.

The numbers are the lowest on record since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking comparable figures in 1983. And they are likely to get worse, as the labor movement faces unified Republican control in Washington, increasingly hostile state governments, and a looming conservative Supreme Court majority that many believe will move to limit the powers of public sector unions.

In some regions, aggressive anti-union efforts by state governments have left the union movement in even worse shape than national numbers suggest. In South Carolina, Texas, and Utah, union membership dips to less than 5% of the workforce.

“The Labor Department statistics announced today are evidence that decades of relentless attacks from right-wing politicians and corporate special interests have taken their toll," said Lee Saunders, president of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, in a statement.

Business groups cheered the numbers.

Randy Johnson, senior vice president of labor issues at the US Chamber of Commerce, said the decline is a sign that "workers remain uninterested in the product that the unions are selling."

Richard Berman, executive director of the conservative Center for Union Facts, said in a statement that "the sad state of private-sector union membership reveals that union bosses are historical artifacts in 21st-century workplaces."

"Despite spending millions of dollars on campaigns like '$15 and a Union' while receiving unprecedented help from the pro-union Obama administration, Big Labor is seeing only dark days ahead," he said.

But Catherine Fisk, professor of Labor Law at the University of California, Irvine, said the events of the 1920s could give some hope that the share of unionized workers will rise again.

"It fluctuated sharply then, from about 1/5th of the nonagricultural workforce being unionized in the early '20s to about where it is now in 1930," she said. "And then it rose sharply from 1935 onward, as workers gained legal protection for unionizing and, significantly, as they saw that unionization was the only way they would secure increased pay and improved working conditions."

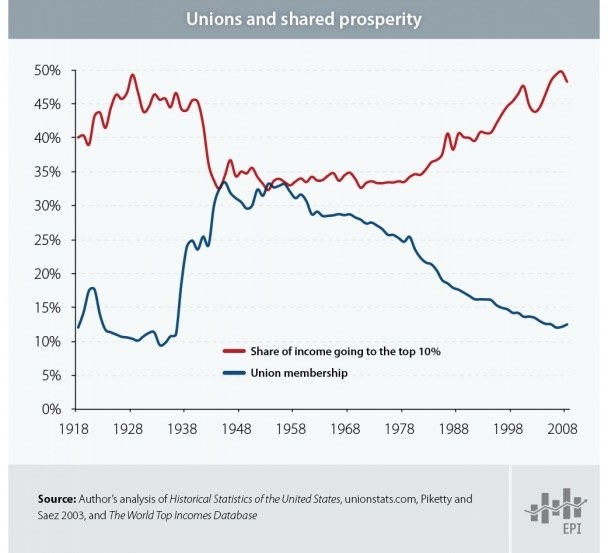

Data looking back further — which isn't exactly comparable to the BLS numbers — shows unionization rates were at 2016 levels in the late 1920s. Back then, the fraction of total income captured by the country's wealthiest 1% was also roughly where it is now.

The top 1%'s share then declined, beginning in 1936, as unionization rates rose, and started to climb again around 1980, as unionization rates fell.

"At some point, if workers become convinced that things are bad enough, we can expect that they may decide to band together to improve their working conditions," said Fisk. "It happened in the mid- to late 1930s, and it can happen again."