In a Washington, DC, hotel ballroom, Sean Spicer, the former White House spokesman, sat on the stage at a sold-out conference of more than 600 HR professionals. One — a woman, like the majority of HR managers — asked Spicer what kind of example it set that President Trump, a former CEO, had faced no consequences after multiple allegations of sexual misconduct.

Spicer said this was the voters’ choice.

“Elected people are in a very unique position because the people elected them into office,” he said. “That is the HR department, so to speak.”

Before allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein inspired people from all walks of life to say #MeToo, the people of SHRM (the Society for Human Resource Management, casually pronounced “Sherm” among members) focused on making sure companies were compliant with federal discrimination law. The 2016 conference emphasized health care, family leave, overtime, social media, and other quandaries.

Avoiding a lawsuit isn’t enough to protect their companies’ reputations and retain talented workers.

But at this year’s meeting, HR leaders faced an unavoidable urgency to plan for what comes after the country’s sexual harassment reckoning. Since last fall, HR departments have found themselves slammed for failing to take action against egregious harassment and now are under pressure to show the profession can take prevention seriously. That’ll mean breaking old patterns by trading generic anti-harassment training for more innovative programs, earning employees’ trust, and convincing corporate leaders — who are overwhelmingly male — that keeping high-earning “rock stars” who misbehave often ends up costing companies money. Avoiding a lawsuit isn’t enough to protect their companies’ reputations and retain talented workers.

“This is a bigger cultural question,” said Johnny Taylor, a former employment lawyer and HR executive who became SHRM’s president and CEO just months before the New York Times’ and New Yorker’s reports on Weinstein. “Culture is at the root of this. I can train all day, I could take my former management team and give them an hour a week of sexual harassment training, and that would not eliminate sexual harassment in the workplace.”

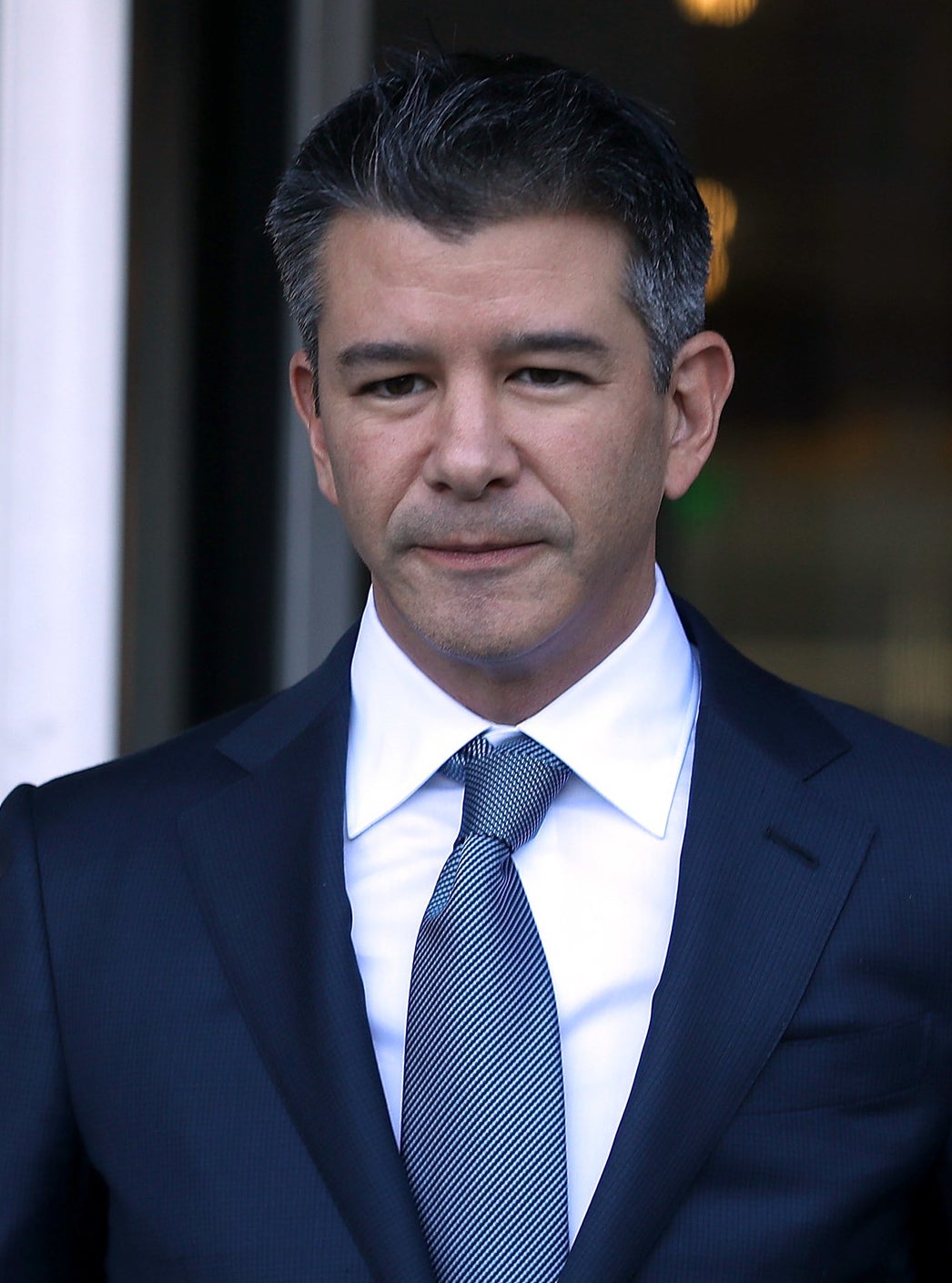

Take the case of Uber, where what started as an HR matter turned into a public scandal that prompted a customer boycott and contributed to the resignation of founder Travis Kalanick as CEO. In one of the conference’s breakout sessions, employment lawyer Brenda Kasper walked dozens of HR managers through former Uber engineer Susan Fowler’s viral blog post recounting her experiences at the company: a sexual advance from her manager, then when she reported it, an effective ultimatum from HR that she could move to another team or likely face a poor performance review.

As for the man, repeated reports of bad behavior had been excused because he was a “high performer,” Kasper said.

Each piece of the story was met with tones of disbelief or groans. Some in the room shook their heads. “Who are these people?” one woman said.

The red flags were obvious to the conference crowd. But in the “move fast and break things” culture of Silicon Valley startups, details like job descriptions, performance reviews, and policies on work relationships can go by the wayside. And those HR fundamentals remain as important as ever, Kasper said, a conclusion that was also reached by former attorney general Eric Holder in his investigation of Uber’s workplace culture.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway in Holder’s report for HR managers: High performers shouldn’t be given a free pass.

“If rock star culture means ‘behave badly and we don’t do anything about it,’ don’t let it happen,” Kasper said.

Of course, getting that message through to executives concerned about earnings isn’t easy for HR professionals, who are there to protect employees but who work for the very companies that might be allowing mistreatment to occur. (And HR employees aren't immune to mistreatment themselves: When an informal poll during lunch asked how many conference attendees had been the victim of sexually harassing behavior on the job, more than half who responded said they had.)

“It’s hard to walk that line of being part of the management team and being an advocate for the employees at the same time,” said Cynthia Thompson, who worked in HR for 33 years before becoming editor and publisher of HR Professionals magazine. “Where do you draw the line? When do you become the spokesperson for senior leadership as opposed to the spokesperson for the little guy, the employees? That’s the hardest part of being in human resources, I think.”

And taking a stand in opposition to senior leadership can open a chief human resource officer up to being the victim of retaliation herself, she told BuzzFeed News.

“All of a sudden, you’re just pushed out,” she said. “But they’ll never say it’s because of the stand you took. It’s just, ‘You don’t fit anymore in our culture.’”

Thompson said one solution is for publicly traded companies to enable HR leaders to report serious issues to the board of directors, to get around the mostly white, mostly male “C-suite” executives if necessary.

In addition, HR professionals agree that good training needs to take place in person, not online, and must be relevant to the specific workplace, whether that’s a restaurant whose servers face sexual comments in the kitchen or a factory whose foreman tries to trade favorable assignments for sex.

Over the years, sexual harassment training programs have become a cottage industry, and some states have moved to require some form of anti-harassment training for companies over a certain size. But as the EEOC found in 2016, most don’t really work. They may shield the company from liability but do little to prevent bad behavior.

The in-house lawyer found that calendars featuring women employees had been given as a gift for the boss’s birthday.

Increasingly, training is incorporating ways for bystanders to take action if they witness harassment, a concept cribbed from college sexual assault prevention efforts. When bad behavior doesn’t rise to the level of illegal sexual harassment, it should still be punished — but in a way that’s proportionate to the conduct, said Jonathan Segal, an employment attorney who specializes in training and policy. And employees need to know that HR and management will respond to complaints in a way that’s fair to victims and to those they accuse, he said.

“People may suffer in silence for fear that if they complain, someone will lose their job,” he said.

And everyone within the workplace needs to be clear on company policies against retaliation.

Segal recalled one executive who asked him what he should say when he encountered an employee who a day earlier had filed a complaint about a colleague.

How about “good morning,” Segal advised him. Simplicity aside, he explained, avoiding someone who has complained about the workplace may not rise to the level of illegal, but it is a form of retaliation.

“It sends a message that if you complain, you don’t exist,” he said.

When training takes place, company leaders need to be there alongside middle managers and employees, he said. They ultimately need the training themselves, and it holds them act as role models.

Another solution is to shift away from training that teaches how not to harass to training that focuses on good behavior: how to interact with people who are different, how to be civil, and how to show respect, Mark Fogel, an HR consultant, told BuzzFeed News. Small, positive moves toward diversity and respectful behavior among colleagues add up.

To change a culture, it’s important to know where you’re starting from, said Linda Seabrook, general counsel for Futures Without Violence, which provides resources on workplace sexual harassment and violence through its Workplaces Respond initiative. An anonymous, confidential “climate survey” can reveal employees’ views on what misconduct is taking place, how widespread it is, and whether they believe it’ll be addressed fairly.

Giving employees a voice also gives them a stake in creating a respectful environment where sexual harassment won’t flourish.

“If you can get employees to buy into what those workplace expectations are, and to have a sense of ‘we’re part of building the kind of workplace we want to be in,’ it’s the ounce of prevention is a pound of cure,” she told BuzzFeed News.

She also called on HR departments to do a “culture walk,” a walk-through of the workplace to see what messages the company is sending about its priorities. It could be how offices are assigned, or how common space is used. At one entertainment company, for example, Seabrook said the in-house lawyer found that calendars featuring women employees had been given as a gift for the boss’s birthday.

“They were not in bikinis or anything, they were fully and professionally clothed,” she said. “But those calendars were up in every cubicle, every office.”

The unspoken message left the lawyer stunned, she said. If Miss January, for example, spoke up in a meeting, would her words be taken as seriously as those of a male colleague?

It was one sign of bigger problems, which leaders did little to address. Finding the bosses unsupportive, the lawyer ultimately left the company, Seabrook said.

“It just demonstrates that culture comes from the top.” ●