Even when under heightened scrutiny after a botched execution that resulted in an eight-month moratorium on executions in Oklahoma, a review of the state's actions during the past week revealed the Oklahoma Department of Corrections is still not consistently following all of its execution procedures.

After courts signed off on the execution of Richard Glossip on Wednesday, the Oklahoma Department of Corrections and Gov. Mary Fallin had to announce that a drug mix-up meant they would be unable to carry out his execution. Fallin, who has opposed Glossip's attempts to halt his execution, requested a temporary stay Wednesday.

A day later, Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt asked a state court for an indefinite stay of all upcoming executions — and raising his own questions about the Department of Corrections's ability to carry out its execution protocol.

"Until my office knows more about these circumstances and gains confidence that DOC can carry out executions in accordance with the execution protocol, I am asking the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to issue an indefinite stay of all scheduled executions," Pruitt said in a statement accompanying his court filing on Thursday.

On Friday, the court granted Pruitt's request, staying all upcoming executions in the state. The court requested updates on the investigation every 30 days.

It would have been Oklahoma's second execution since it botched the execution of Clayton Lockett in April 2014. Lockett writhed on a gurney and sat up in an ordeal that lasted 43 minutes. The mistakes that led to yesterday's delay mimic some of the state's errors in the Lockett botch.

"What happened yesterday raises the question of whether the Department of Corrections is even competent to carry out the ultimate sanction the state can impose," Glossip's attorney, Dale Baich, said. "The state assured the federal court and the public that any problems were fixed, and that it had an improved protocol and a shiny new execution chamber. Now this."

A review of the state's execution protocol and the actual implementation of Glossip's planned execution this week in fact show multiple areas where the state either did not follow the protocol or interpreted it in an unexpected way in order to claim compliance.

After Glossip's execution warrant had become valid, corrections personnel discovered they didn't have the right drugs in stock. Oklahoma's three-drug protocol for lethal injections calls for potassium chloride to be used as the last drug: the one that kills. The state instead received potassium acetate and did not notice the mix-up until the day of the execution.

The Department of Corrections received the drugs in a sealed box on Wednesday and did not open it until that afternoon, saying it is unable to store drugs on site without a DEA license.

But the claim that the Department of Corrections couldn't obtain the drug before the execution without a DEA license isn't true.

Both potassium chloride, the third drug Oklahoma wanted to receive, and potassium acetate, the drug Oklahoma did receive, are not on the DEA's list of controlled substances. Neither is rocuronium bromide, which is the second drug in the protocol.

Midazolam, the first drug in the protocol, is a controlled substance. The Department of Corrections could have received and stored the potassium chloride and rocuronium bromide at any time and waited for the midazolam.

When approached with this information, Corrections spokesperson Terri Watkins said on Friday "We receive the drugs together."

When BuzzFeed News pointed out they could have asked for two shipments, Watkins would only say, "No."

At a press conference Thursday, Department of Corrections Director Robert Patton said the supplier of the drugs, which the state keeps secret, made the decision on its own to switch out the drug after it could not obtain the correct one. According to Patton, when contacted about the mix-up, the supplier told state officials the drugs are interchangeable.

Oklahoma's execution protocol, which has been approved for use by the courts, specifically calls for potassium chloride as the third drug. No state is known to have tried using potassium acetate as a substitute.

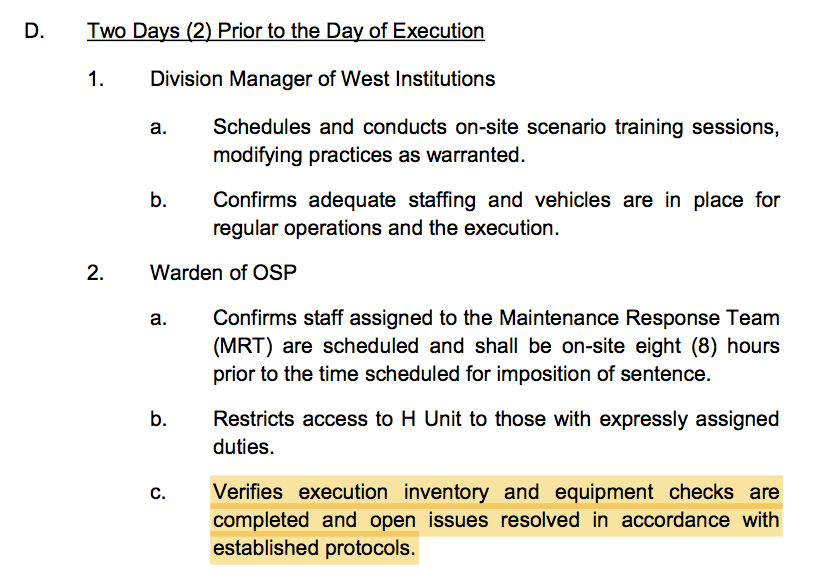

In addition to the matter of the drug itself, the mix-up should have been noticed much earlier under the state's protocol. It specifically requires Warden Anita Trammel to make sure that execution drugs and equipment are on hand two days in advance of an execution.

Fallin's office disagreed that the protocol requires the warden to verify the inventory of drugs, arguing that "execution inventory" instead refers to other things executions require, like syringes. Spokesman Alex Weintz said there is no timeline for checking the inventory of execution drugs.

Attorney General Scott Pruitt's office did not respond to a request for comment. But in a court filing asking for three executions to be postponed indefinitely, his office admitted proper procedures were not followed.

"The Attorney General needs time to evaluate the events that transpired on September 30, 2015, ODOC's acquisition of a drug contrary to protocol, and internal procedures relative to the protocol," Pruitt's office wrote. "The State has a strong interest in ensuring that the execution protocol is strictly followed."

In a statement, Pruitt said he wasn't notified of the error until shortly before the scheduled execution.

What makes the mix-up more surprising is the state claimed in August that it had all of the necessary drugs.

"I have received confirmation from the Oklahoma Department of Corrections that sufficient drugs to carry out the executions of Richard Glossip, Benjamin Cole and John Grant have been obtained," an assistant attorney general wrote to Glossip's attorneys on August 11. "The drugs are midazolam, rocuronium bromide and potassium chloride."

But Fallin said at a Wednesday press conference that the state didn't even receive the drugs until the day of the execution. And it wasn't the warden that noticed the mix-up. It was the doctor.

Asked about the discrepancy, Fallin's spokesman said the Aug. 11 letter had "unclear drafting."

"It says DOC has 'obtained' midazolam and other drugs," Weintz said. "DOC had, or thought they had, 'obtained access' to those drugs. They would never have had them physically present at the penitentiary."

The Department of Corrections and Attorney General Scott Pruitt did not respond to questions.

"The Department of Corrections follows the protocol, except when it doesn't," Baich said. "In August, the DOC said it obtained the drugs to be used in Mr. Glossip's execution. On Monday, the DOC was supposed to verify that it had what it needed to carry out the execution set for Wednesday. We learned yesterday that the DOC did not obtain the drugs until Wednesday morning. DOC's representation in August, which was part of a court filing, is inconsistent with the governor's statement on Wednesday."

According to thousands of pages of interviews conducted by the Oklahoma Department of Public Safety following Lockett's botched execution, obtained by BuzzFeed News, execution personnel complained that the Department of Corrections didn't have the proper equipment — the right size needles — for the execution.

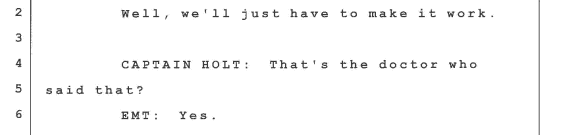

"So I went back into the execution room to get a -- to see if I had a 2 ½ inch 14-gauge [needle]," the EMT, a member of the execution team, told investigators afterward. "That's what you're going to need for a femoral. Didn't have one."

"All I had was the inch and a quarter and I told [the doctor] three times, 'All I have is an inch and a quarter [long needle], but I've got a 14 [gauge needle] and I've got a 16 [gauge needle].'"

According to the EMT, the doctor said, "Well, we'll just have to make it work."

The DPS summary of their investigation stated IV issues were the cause of the botch, and that executioners lacking the correct equipment contributed to it.

"The physician requested a longer needle/catheter for femoral access," the report said. "The paramedic attempted to locate a 2 or 2 ½ inch, 14 gauge needle/catheter, but none were readily available. The physician also asked for an intraosseous infusion needle, but was told the prison did not have those either. Both agreed their preferred needle/catheter would have been 1 ¾ to 2 ½ inches. The physician had never attempted femoral vein access with a 1 ¼ inch needle/catheter; however, it was the longest DOC had readily available."

But on Wednesday, unlike the Lockett execution, state officials called off the execution when corrections employees realized they didn't have the proper supplies.

The DPS summary of the Lockett botch also criticized other preparations before the execution, namely training.

"The investigation revealed areas of training that need to be addressed. It was noted that there was no formal training process involving the paramedic, the physician or the executioners and their specific roles," the report said, adding that both the warden and the Director of the Department of Corrections both acknowledged training was inadequate.

Right now, Oklahoma has not specified how it hopes to proceed. It could attempt to get a hold of the correct drug, or the attorney general could litigate in favor of allowing the drug it does have — potassium acetate — to be used.

Oklahoma had two executions scheduled for this month, with one taking place next week, although the court has now delayed them indefinitely.

Glossip faces the death penalty for plotting the murder of his former boss, Barry Van Treese, in 1997. He has maintained his innocence and the case against him relies upon the testimony of Justin Sneed, the man who murdered Van Treese and did not receive the death penalty.

By the time new execution dates are set, a new Oklahoma law will have kicked in that allows for death by nitrogen gas if lethal injection drugs are not available. Oklahoma does not currently have a protocol governing the use of nitrogen gas, and the Department of Corrections said it would not use that method anytime soon.