WASHINGTON — At the Friday night news conference in Boston following the apprehension of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, one of the Boston marathon bombing suspects, U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz said the federal government could invoke the "public safety" exception to the well-known Miranda rights usually read to suspects when brought into custody.

"There is a public safety exception in cases of national security and potential charges involving acts of terrorism, and so the government has that opportunity. Right now, though, I believe that the suspect has been taken to a hospital," she said in response to a question.

A Justice Department official later Friday night told Politico the exception was being invoked: "No Miranda warning to be given. The government will be invoking the public safety exception."

Earlier in the day, Sen. Lindsey Graham had raised the possibility on Twitter:

The last thing we may want to do is read Boston suspect Miranda Rights telling him to "remain silent."

The last thing we may want to do is read Boston suspect Miranda Rights telling him to "remain silent."-- Lindsey Graham

The last thing we may want to do is read Boston suspect Miranda Rights telling him to "remain silent."-- Lindsey Graham

The Obama Administration needs to be contemplating these issues and should not rush into a bad decision.

The Obama Administration needs to be contemplating these issues and should not rush into a bad decision.-- Lindsey Graham

The Obama Administration needs to be contemplating these issues and should not rush into a bad decision.-- Lindsey Graham

So, what is the public safety exception?

Police don't need to read Dzhokhar Tsarnaev his Miranda rights immediately, government lawyers have argued, because of a 1984 Supreme Court case that gives police a "public safety exception" to reading a suspect the well-known right to remain silent.

The government can use the exception when concerns about the public's safety exist. Under it, the government is legally allowed to seek information related to those safety concerns without Tsarnaev having notice of those constitutional rights available to him.

The public safety exception, however, only applies until police "secure their own safety or the safety of the public," so it is limited in its use before a suspect is read his rights and would be charged and tried under the normal criminal justice system.

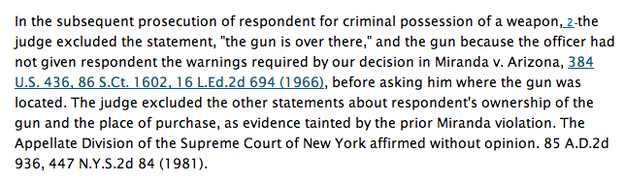

The 1984 case, which dealt with finding a rape suspect's gun, has been adopted by the federal government as a "powerful tool" for use in terrorism investigations. In the case, Benjamin Quarles had made statements about the location of a gun after being caught by police, but before he was read his Miranda rights.

The lower courts had prohibited the prosecutor from introducing either the gun itself or Quarles' statement about the location of the gun as evidence at trial because he had not been read his Miranda rights.

As the Supreme Court described it:

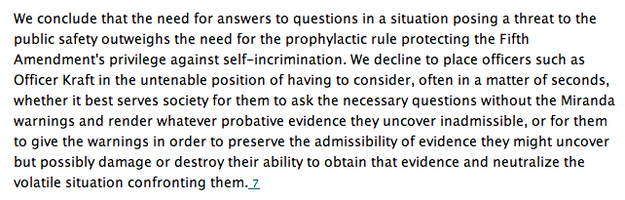

After considering the purposes for the Miranda warning, as well as the need for police to be able to take action to protect the public, the justices, led by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, concluded:

The court added, "The exception will not be difficult for police officers to apply because in each case it will be circumscribed by the exigency which justifies it. We think police officers can and will distinguish almost instinctively between questions necessary to secure their own safety or the safety of the public and questions designed solely to elicit testimonial evidence from a suspect."

A secondary issue of "presentment" — when the suspect is brought before a judge for an initial court appearance — also has been raised in various terror cases, as detailed in 2010 by Politico's Josh Gerstein, and could serve as another limit in the time that Tsarnaev could be held without being given notice of constitutional rights.

Under Supreme Court precedent, although there are exceptions, a delay of more than six hours before a suspect is brought before a judge could lead to statements made after that time from being excluded from trial. A suspect can waive presentment, however, which the government has sought and obtained from suspects in the past.

What does the FBI think about the public safety exception?

Citing Quarles' case in a 2010 memorandum about "Custodial Interrogation for Public Safety and Intelligence-Gathering Purposes of Operational Terrorists Inside the United States," the FBI advised the following guidance for "the use of Miranda warnings for custodial interrogation of operational terrorists who are arrested inside the United States":

If applicable, agents should ask any and all questions that are reasonably prompted by an immediate concern for the safety of the public or the arresting agents without advising the arrestee of his Miranda rights.

In explaining the application of the exception to terrorism suspects, the FBI's Carl Benoit wrote:

Recent and well-publicized events, including the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 235 near Detroit, Michigan, on December 25, 2009, and the attempted bombing in New York City's Times Square in May 2010, highlight the importance of this exception. Those current events, occurring in a time of heightened vigilance against terrorist acts, place a spotlight on this law enforcement tool, which, although 26 years old, may play a vital role in protecting public safety while also permitting statements obtained under this exception to be used as evidence in a criminal prosecution. In brief, and as discussed in this article, police officers confronting situations that create a danger to themselves or others may ask questions designed to neutralize the threat without first providing a warning of rights.

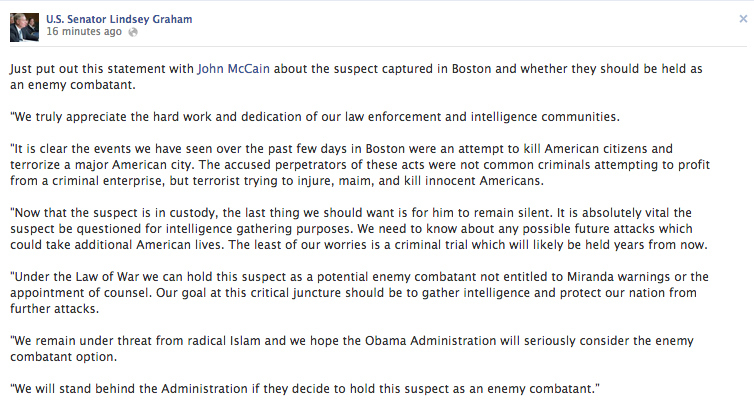

Graham, joined by Sen. John McCain, would go further:

[UPDATE at 10:30 a.m. April 20: This post was updated to reflect the report that the government was invoking the public safety exception in this case.]

[UPDATE at 12:05 p.m. April 20: This post was updated to include discussion of presentment issues.]