WASHINGTON — The Justice Department argued in court this week that officials don’t have to turn over certain information and documents about President Trump’s announced decision to bar transgender people from serving in the military — citing executive privilege.

The judge hearing one of the lawsuits challenging the policy pushed back against the Justice Department lawyer's claim. The judge said Trump administration officials were incorrectly arguing that an “absolute” privilege — meaning one that the judge could not rule against — protected the administration from having to turn over certain information regarding meetings or conversations the president had in advance of his July 26, 2017, tweets announcing an end to transgender military service.

“After consultation with my Generals and military experts,” Trump wrote in a series of three tweets, “please be advised that the United States Government will not accept or allow Transgender individuals to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military. Our military must be focused on decisive and overwhelming victory and cannot be burdened with the tremendous medical costs and disruption that transgender in the military would entail. Thank you.”

Nearly a month later, Trump issued a further policy that directed the end of transgender service this year.

In a docket entry detailing the outcome of a telephone conference, US District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly stated that she hopes to move the issues forward in a follow-up telephone conference Friday. The judge laid out that both sides should be ready to discuss issues relating to two types of executive privilege raised by the Justice Department in the case: information the federal government “contend[s] is covered by the presidential communications privilege” and a dispute “regarding the deliberative process privilege.”

Executive privilege, while a term familiar to most Americans, is much more complicated — and dependent on the facts of specific cases — than often portrayed. It’s a rarely invoked set of different, but related, privileges that are available to protect executive communications from disclosure to courts, Congress, and often — ultimately — the public.

Often, the privileges, even if they cover the communication, are not enough to keep some documents from being turned over or testimony from being compelled if the information at issue is necessary for a congressional or legal matter to be able to proceed, it isn't available elsewhere, and the branch seeking the information is willing to fight for it. At the same time, judicial and congressional officials often negotiate out executive privilege–related disputes before they get to a final court ruling, due to concerns about separation of powers — meaning there isn't always clearly established law on specific executive privilege–related issues.

The presidential communications privilege and deliberative process privilege have related purposes: keeping executive branch decision-making private. As the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit put it in a 1997 case, “Both are executive privileges designed to protect executive branch decisionmaking, but one applies to decisionmaking of executive officials generally, the other specifically to decisionmaking of the President” and his senior advisers, as the court held in that opinion.

Of the two, the deliberative process privilege is more limited. It only protects “predecisional” material that is “deliberative” in nature, like drafts of materials and policy recommendations to superiors. Because of these limits, factual material, like raw data collected by an agency, generally is not protected — and the privilege can be overcome with “a sufficient showing of need” for the material by the requesting party. Notably, the privilege generally does not protect against disclosure when misconduct is alleged.

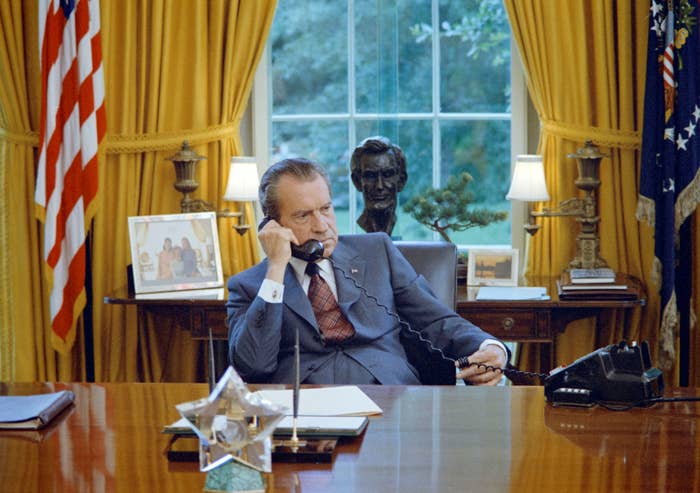

The presidential communications privilege, on the other hand, is a more robust privilege that the Supreme Court addressed in the 1974 case over then-president Nixon’s White House audio tapes — and whether a court could order that they be turned over for a pending criminal trial of one of Nixon’s associates. The Nixon administration — citing the importance of protecting “the independence of the Executive Branch within its own sphere” — claimed an absolute privilege against disclosing the tapes as part of an ongoing criminal prosecution.

The Supreme Court held that “high respect” must be given “to the representations made on behalf of the President” — justifying a “presumptive privilege” for presidential communications, including factual communications. The court nonetheless ruled that a “generalized” assertion of the presidential communications privilege is not absolute and must be weighed against the need for the material by the other party seeking it — whether it be a court or Congress. In the Nixon case, the court held that the “demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial” outweighed Nixon’s invocation of executive privilege.

In the case over the transgender military policy, the Justice Department lawyer, Ryan Parker, raised the presidential communications privilege in response to a request from the challengers, who have asked for information from the president about the identities of the consulted general and military experts referenced in the tweets, and what relevant meetings and conversations took place about the issue.

“[Y]ou've taken the position, it seems to me, or almost the position that it's an absolute privilege, and that's not correct,” Kollar-Kotelly said, criticizing the Justice Department’s position. At another point, she explained further: “[I]f you assert [the presidential communications privilege], it's presumptively so, but that is not the end of the inquiry. And the problem that I'm having is, you're not willing to have the rest of the inquiry with me.”

As a way of addressing the government’s concerns, Kollar-Kotelly discussed the possibility of the department turning over a log detailing the relevant meetings and conversations — not the content of the communications, just the fact of their existence — for her to review in an effort to determine if the privilege applies, but the DOJ lawyer kept insisting that the department’s position was that such a document would be covered by the privilege.

The DOJ lawyer didn’t budge.

After significant back and forth, the judge said, “I'm not talking about giving it to the plaintiffs. You keep going back to the plaintiffs. I am talking about giving it to the Court so the Court can make a decision as to whether or not this actually falls into the presidential communications privilege.” Finally, Kollar-Kotelly said, “[A]nswer it yes or no and give me an explanation. Are you willing to provide any information whatsoever about what might have transpired?”

“Your Honor, to answer in one word, the answer is no,” Parker responded.

Concluding the discussion a few minutes later, Kollar-Kotelly said, “I will figure out how I want to proceed with this, but this is not a good way to go about this.”

The deliberative process privilege discussion, surrounding withheld documents and redactions to documents that have been turned over, was more brief and less contentious, focusing in large part on a dispute over what constitutes a “decision” — given that the privilege only protects predecisional matters.

The dispute, as Kollar-Kotelly put it, appeared to be over “whether the tweet was the decision or the memorandum was the decision.” She suggested that decision-making is fluid at times and that, “instead of going off on whether the tweet is the final decision or his memorandum is the final decision,” the lawyers should focus on whether the material at issue looks like the matter discussed is the type of material that usually would be seen as predecisional.

The challengers’ lawyer, Paul Wolfson from WilmerHale, said the government needed to specify what decision is at issue so it can be determined if the redacted material truly is predecisional or if it is “really just people reacting to a decision that was already made, which would make it postdecisional.”

Parker’s response was a bit winding, but it, in effect, said that the tweets set off a cascading series of decisions — “the tweet was a decision and that that decision itself gave rise to a series of additional decisions” — and that the redacted materials are all “deliberative material” protected from disclosure because the redactions represent predecisional material as to at least one of those decisions.

Kollar-Kotelly asked the parties to confer on those issues in an attempt to narrow down the number of documents at issue before she has to determine how to address the privilege claims.

Over the course of the hearing, lawyers for both parties referenced letters that were submitted to the court and each other, laying out their positions on the arguments. Neither letter was posted on the court's docket, however, and both lawyers for the challengers and for the government declined to provide a copy of the letters to BuzzFeed News — saying the decision was up to the judge to make the letters public. On Friday morning, just before publication of this story, BuzzFeed News was informed that the court would be placing the letters on the docket at the request of the parties — but it had not done so by the time of publication.

“I will figure out how I want to proceed with this, but this is not a good way to go about this.”

This week’s court dispute is not the first time the Trump administration has raised the argument that documents sought in litigation should be protected from disclosure by executive privilege. In December, in the course of defending the administration’s decision to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, a discovery dispute arose in one of the challenges to the decision. A federal judge ordered the Trump administration to turn over documents in a challenge, claiming the decision violated the Administrative Procedure Act. The Justice Department went to the Supreme Court to halt that order from being enforced, making several arguments regarding why the order was inappropriate, but one of its final arguments was that at least some of the documents were covered by executive privilege and should not have to be produced.

The Supreme Court granted the Justice Department’s request on the grounds that the discovery order was premature, but the court added a warning regarding privilege issues. Near the conclusion of its order, the court noted, “In any event, the District Court may not compel the Government to disclose any document that the Government believes is privileged without first providing the Government with the opportunity to argue the issue.”

Of course, executive privilege issues also are expected to come up — and already are coming up — in the course of the special counsel and congressional investigations into Russian influence into the 2016 presidential election. While these other disputes are important in their own right, the government’s arguments in other cases shed light on what might be expected, should special counsel Robert Mueller seek information the administration doesn’t want to turn over or, as could happen with Steve Bannon, if a chamber of Congress votes to hold someone in contempt in response to a refusal to answer questions or provide documents.