In the early months of 2000, aides inside President Bill Clinton’s White House faced a dilemma.

Californian voters would soon vote on a ballot measure to ban the recognition of marriages between same-sex couples. Should Clinton speak out against the California initiative, as the two leading Democratic candidates running for president had done? What could Clinton say?

Just four years earlier, Clinton had signed the Defense of Marriage Act, the law that stated the federal government would not recognize the marriages of same-sex couples as valid and states didn’t need to do so, either.

After a prominent Democrat raised the issue of California initiative, Proposition 22, with the president, his deputy chief of staff sent an email to several senior aides.

Clinton “would like to” oppose Prop 22, she wrote, “but he asked that we figure out how to square it [with] the fact that he signed [DOMA].”

After significant internal debate over how the federal law was different from the California proposal — or whether it was even different at all — one of Clinton’s senior legal advisers put forward a new idea.

“What about this?” wrote Eddie Correia, the president’s special counsel for civil rights.

“I now conclude that I was wrong about same-sex marriage,” Correia wrote, in a draft statement meant to be delivered by Clinton. “I continue to believe that the people of California should be able to decide what marriages they will recognize. But I hope they will choose to recognize the validity of marriage between people of the same gender if the marriage is legal where it occurred. Consequently, I am opposed to Proposition 22.”

Clinton, however, would never make the statement. As far as Correia knows, the president never even saw it. The idea was almost immediately dismissed by Eric Liu, the president’s deputy domestic policy adviser.

“Well, let’s not go there yet, and let’s certainly not start there,” Liu wrote in response to Correia’s draft statement.

Clinton ultimately opposed Prop 22. But his statement against it — delivered at a fundraiser for Sen. Dianne Feinstein less than a week before the vote — was narrow, glossing over what he thought about the larger question of marriage equality and leaving out entirely the subject of DOMA.

The measure, Clinton would say, was unnecessary and divisive.

Fifteen years later, Eric Liu regrets his quick dismissal of the idea that President Clinton could admit he was wrong about marriage equality in 2000.

“There’s a poignant regret that I have about that — that my mindset was, ‘Let’s not reopen the DOMA can of worms. Let’s figure out a way to be opposed to this without doing that,’” Liu told BuzzFeed News this week. “It’s hard to rewind and ask, but the ‘what if’ question is, ‘What if we had actually had a critical mass of people within the White House who really wanted to reopen that question?’”

Neither the Clinton Foundation nor the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign responded to a request seeking comment from President Clinton for this story.

Bill Clinton wouldn’t publicly support marriage equality until 2011, Barack Obama wouldn’t do so until 2012, and Hillary Clinton didn’t announce her support until 2013 — the same year that the Supreme Court struck down the part of DOMA that barred federal recognition of same-sex couples’ marriages. Now, the country awaits another Supreme Court ruling, this one on whether state bans on marriages between same-sex couples and their recognition are constitutional.

In 2000, there were no states that allowed or legally recognized those marriages. But even then, officials across the country were increasingly being forced to confront questions about whether and how same-sex couples should have their relationships protected and recognized — and fierce opposition to any formal recognition. In response to a 1999 state supreme court ruling, Vermont would soon decide to avoid granting equal marriage rights to same-sex couples by creating an entirely new entity: civil unions. It would not be until 2004, in Massachusetts, that same-sex couples anywhere in the country could legally marry.

The internal White House debate over Prop 22, which offers candid insight into that very unusual moment in time, has not been reported on before. The emails were only made public this year when the Clinton Library released thousands of pages of documents from the Clinton White House covering various issues relating to same-sex couples’ marriage rights. BuzzFeed News found Correia's proposal, Liu's response, and a cache of related documents spread throughout the boxes of documents released earlier this year.

The emails also feature a cadre of top former Clinton White House staffers — including two who have even more political influence today, Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney and Democratic strategist and longtime Clinton ally Minyon Moore — right in the middle of the debate.

For his part, Correia remains glad that he made his proposal, he told BuzzFeed News, even if he knew it was unlikely to happen.

“It seemed to me that it was at least worth considering — that you could change your mind” on the issue of same-sex couples' marriage rights, he said. “It was something you could change your mind on.”

Even the idea of President Clinton opposing the California measure restricting recognition of marriages to opposite-sex couples at all, however, was a matter of debate within the White House in early 2000.

Concerned that reporters might be asking about administration’s view on Prop 22 — also called the Knight initiative after the state senator backing the measure — a White House press aide raised the issue first thing Friday morning, Feb. 25.

The initial response prepared by Mary Smith, the associate director of policy planning in the Domestic Policy Council, was “short and simple,” as a colleague put it. “The administration does not have a position on this specific ballot measure in California,” she wrote in her draft statement in part.

At roughly the same time, however, another group of White House staffers — including the new gay and lesbian liaison, Julian Potter — already had been preparing a different path forward: one opposing the initiative as “counterproductive” and “divisive” and asserting that it “does not support the administration efforts to create a more fair and just society.”

An hour before lunch, Potter made it clear to the press office that there was no answer yet: “[T]wo versions. Very different.”

In the interim, compromise language was reached for the press office: “I do not know if the Administration has taken a position on this specific ballot measure in California.”

Karen Tramontano, Clinton’s deputy chief of staff, responded to that language with an important update. The Democratic National Committee’s new treasurer, Andy Tobias — a prominent gay donor — had spoken with Clinton about the measure. He told the president, as Tramontano put it, that “he thought it would be important for the president to take a stand against the initiative” and that “the president said he would like to” do so.

The discussion, however, quickly turned to the complications caused by the fact that Clinton had signed the Defense of Marriage Act — which appeared to do a very similar thing as Proposition 22 would do. Was there a way to distinguish Prop 22 from DOMA?

Tramontano noted that while there had been a discussion about “how to square the circle,” distinguishing DOMA from Proposition 22 “seems problematic.”

The Domestic Policy Council staff, who initially had recommended taking no position on the measure, now proceeded to take the new marching orders, trying to figure out if there was any real difference between DOMA and Proposition 22.

Three days later, on Monday, Smith sent Liu “a few bullets” that attempted to draw distinctions between the two measures. But, she also wrote bluntly at one point, “This is basically California’s DOMA law.”

She went on, though, to note that Al Gore and Bill Bradley — who were squaring off for the Democratic presidential nomination — were “walking a fine line” of opposing same-sex couples’ marriage rights but also opposing Prop 22. “The main reason they seem to have given to oppose it,” she wrote, “is that it is divisive and unnecessary.”

Smith also noted that Correia in the counsel’s office had suggested that the White House could argue that Proposition 22 would violate the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the Constitution. She did not recommend taking that route, however, calling it a “dangerous argument … given that the federal DOMA is probably constitutionally suspect as well.”

The offhand comment is striking. In 1996, when DOMA was under consideration in the House, the Clinton Justice Department wrote in a letter to the House Judiciary Committee that “there are no legal issues raised by” DOMA and that it would be “sustained as constitutional.”

Less than four years later, a domestic policy adviser was writing — almost as a given — that DOMA likely was “constitutionally suspect.”

The debate over how exactly Bill Clinton could oppose Prop 22 in light of his support for DOMA would continue over the next several days — but not before Correia would float his proposal for a dramatic policy shift for the Clinton administration to a number of officials, including deputy White House counsel William Marshall.

In his email, Correia didn’t address the constitutional concerns about DOMA. But, in some ways, Correia went much further in his draft statement for Clinton.

“Four years ago, I signed the Defense of Marriage Act, which provides that states should have a choice as to whether they will recognize a marriage between members of the same sex. I still believe states should have that choice,” Correia drafted.

“For many years, I have been personally opposed to same-gender marriages, and, until recently, I would have agreed with those states who choose not to recognize them. After having reflected on the impact of this position on thousands of loving, committed couples, I now conclude that I was wrong about same-sex marriage,” Correia wrote for the president.

Clinton then, in Correia’s draft, would have announced his opposition to Proposition 22 by saying of California’s voters, “I hope they will choose to recognize the validity of marriage between people of the same gender if the marriage is legal where it occurred.”

The draft statement was emailed out at 1:57 p.m. that Monday.

Seven minutes later, at 2:04 p.m., Liu stopped consideration of the draft before it could even begin. Instead, Liu proposed, the “unnecessary” and “divisive” arguments provided a better path to pursue for any potential statement from Clinton.

Talking with BuzzFeed News this past week about the discussions over Proposition 22 and his draft statement, Correia said the back-and-forth debate over the initiative led him to his proposal.

“I thought, rather than continue to parse this California proposition — why you’re against it — just, just say that ‘same-sex marriage is a good thing, and I’ve changed my mind about it’ — and I thought, ‘Why not now?’” he said.

The process, he knew, would have gotten far more complex had the White House pursued his approach. “It would have been something that — if there had been support for actually raising this with the president — it would have required a senior-level political meeting and a discussion with the president,” Correia said, adding, “We never got to that point, as I recall.”

Explaining what happened, Liu told BuzzFeed News, “The way we ended up doing it was kind of to take as a given that there’s DOMA and with that given, kind-of position against it and still signal on Prop 22 that the president’s heart was in the right place. But, the work of politics is always to try to define the frame of the possible. And, at that time, I let my concern about protecting the president preempt expanding the frame of the possible.”

Instead of Correia’s proposal, aides reached a compromise: Clinton would oppose Prop 22, unlike the initial recommendation that he avoid the issue, but he would use the “unnecessary” and “divisive” argument.

“[H]ad a good meeting today,” Sean Patrick Maloney — now a congressman from New York — wrote to Minyon Moore at political affairs at a little past 5 p.m. “[T]hink we’ve reached a good consensus; [Eric Liu’s] drafting up some q& a.”

Looking at some of the documents, Maloney this week described the internal discussion as an effort by Clinton’s staff “to give life to the leader’s desire to speak out against discrimination, even in a tricky context where you’ve got a state ballot initiative that on its face might seem consistent with his previous position on DOMA.”

While the process, at times, looked hectic from the email trails, Moore told BuzzFeed News this week that such a process is precisely how Clinton liked to see discussions proceed.

“I think he’s happiest when he knows that there are opposing views, that there’s a struggle, because he believe we are weighing everyone’s opinion, not just our own,” she said. “And it’s good to have people for and against, because sometimes you miss the substance for the superficial. Just because you are for something doesn’t mean that we can’t see the other person’s point of view, which is what he always stressed.”

On Monday evening, Feb. 28, 2000, the draft Q&A was sent around to several senior staffers. The draft answers for the president stated that Proposition 22 was “unnecessary and divisive” — and characterized the measure as “mainly an unprovoked attempt to pit one group against another and to engage in the politics of division.”

It added, however, a line noting, “I oppose governmental recognition of same-sex marriages, and that’s why I signed DOMA.” Also included was a follow-up statement asserting that Clinton opposed discrimination against gays and lesbians and that he “believe[s] Proposition 22 could do more to provoke instead of prevent discrimination.”

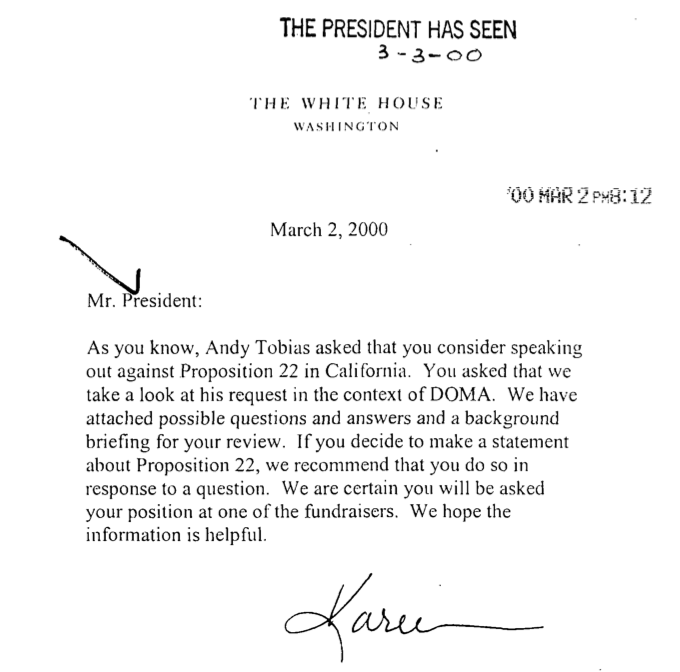

After ironing out some last wrinkles over the next days, the Q&A was finalized. Tramontano provided it to the president, along with a background fact sheet on “Same-Sex Marriage and California Ballot Initiative,” in a memo dated March 2, 2000.

Clinton flew to California, and on Friday evening, attended a dinner fundraiser benefiting Sen. Dianne Feinstein.

“I hope you'll vote against Proposition 22,” he said to applause in a hotel ballroom in San Francisco on March 3, 2000. “However you stand on the question of gay marriage — and I realize that San Francisco is different from the rest of California, is different from the rest of America. But that's not what is at stake here. This initiative will have no practical effect whatever. This is a solution in search of a problem that isn't there.”

He added that “people are being asked to vote on this to get everybody in a white heat and to divide people,” going on to relay a story about a “six-year-old girl killed in Michigan” by another child with a stolen gun and saying, “That's a problem we ought to be working on.”

He went on to mention, among others, Matthew Shepard and James Byrd — two victims of hate-motivated violence — and told the audience that what those and other stories show is that “there's this huge gulf out there, still, in too many places where people wonder if they can be treated fairly.”

Four days later, on March 7, 2000, California voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 22, by a margin of 61%-39%.

The day before the vote, Julian Potter — the gay and lesbian liaison in the White House — responded to an email from Jeff Soref, a prominent New York gay Democratic politico and donor.

“I know how this was done… many fights with WH Counsel and Domestic Policy,” she wrote. Although Potter obviously had professional interests at stake, it is notable whom she chose to praise and how. “I was holding our line here in the WH. Sean [Patrick Maloney] was there at the final meeting….Minyon [Moore] was very helpful and Andy Tobias spoke with the president about it last week.”

Maloney, this week, told BuzzFeed News that he remained “proud” of the president for his opposition to the measure and the “small part” he played in making that happen. “I think from a modern perspective it might seem tame, but at the time, it was no small thing that the president was willing to come out forcefully against an anti-gay ballot initiative.”

Notably, in her email to Soref in 2000, Potter also was blunt about how Clinton’s support for DOMA was a hindrance to getting too far out on the issue, writing, “There was a general fear about getting us into a protracted DOMA conversation … because it is so closely linked to Prop 22.”

DOMA also, Liu acknowledged, limited the thinking on proposals like Correia’s draft statement in support of marriage equality. “When I look back on it,” he said, “certainly, not only by the standards of our times today but by my own standards on this issue, I think I should have pushed harder to expand the frame of the possible.”

Multiple former Clinton aides, however, argue that the Prop 22 opposition alone meant something more in the context of the time, something Liu and Correia acknowledged — and in the concept of “normalizing the conversation,” as Moore put it. Tramontano and Potter did not respond to messages seeking comment, and attempts to reach Smith were unsuccessful.

“I think in 2000 there was almost nobody who was publicly for marriage equality; it was a different world,” Maloney said. “Even people like Minyon and me and Julian, who were pushing for greater tolerance and acceptance within the White House — and the First Lady’s staff as well — no one would have seriously expected the president to come out for marriage at that point. It was a different world.”

Moore contends that much of the work on so-called “cultural” issues is over the question of, “How do you normalize the conversation?”

“I would contend that he started the path of normalizing the conversation around the [LGBT] community,” she said of Clinton. “And you have to start somewhere.”

Eleven years later, Clinton went further down that path, coming out for marriage equality, telling New Yorkers — and the country — in May 2011 that he had reached a decision to support the right of same-sex couples to marry.

“Our nation’s permanent mission is to form a ‘more perfect union’ — deepening the meaning of freedom, broadening the reach of opportunity, strengthening the bonds of community,” Clinton said in a statement released by the Human Rights Campaign. “That mission has inspired and empowered us to extend rights to people previously denied them. Every time we have done that, it has strengthened our nation. Now we should do it again, in New York, with marriage equality.”

For a few minutes more than a decade earlier, though, Eddie Correia had imagined a world in which that would have happened in 2000.

“I think people thought — people higher than my pay grade thought, ‘This is just not realistic,’” Correia said last week. “But, you know, people were changing their minds every day.”