Edith Windsor walks through the lobby of the large Fifth Avenue apartment building just north of Washington Square Park where she has lived for nearly 40 years. "Construction," she says, motioning upstairs. "It's so loud."

Wearing a mauve shirt and a dangling string of pearls, Edie, as she is known, is a proper Manhattan host, even in the morning. And, though her 83-year-old body shows her age and she shakes slightly at times as she speaks, her smile and laughter over the course of the December morning signal a youthful spirit.

A week earlier, on Dec. 7, the U.S. Supreme Court announced the justices will be hearing Windsor's challenge to the constitutionality of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), as well as a challenge to California's Proposition 8 marriage amendment. Windsor's hearing, scheduled for March 27, is a moment that LGBT advocates think will be a defining one for their cause. But Edie Windsor's story is the cause.

For the past three years, that story has played out in federal courthouses. But the real tale is one of how a lesbian in post-World War II America could find, live with and — at long last — marry the love of her life.

"I read a paperback when I first got to New York," Windsor says, herself then a young woman moving to the city to start a new life after having ended a short-lived marriage to a man. "It was about a young woman, a schoolteacher, who had come to New York for her vacation, and she was looking in the mirror. She's all dressed up, and is talking to herself and saying, 'You're in New York City where anything could happen,' and then she says, 'So, what could happen?' 'You could kiss a woman.'"

Windsor's eyes widen: "And I jumped out of my chair and said, 'Where?!'"

Where, for Windsor, turned out to be Portofino, a restaurant in Greenwich Village where Windsor was introduced to Thea Spyer in 1963.

"Somebody brought her over to the table and then it turned out that we were going to the same place after dinner," Windsor says. "So, we did that, and then we went back to Thea's apartment, and we were dancing, and we just kept dancing, until [I had a] hole in my stocking. And, I realized I had to get out of there, I had to get home."

Of that night, which began with Windsor asking a friend to take her to "where the lesbians go," Windsor says, "I suddenly knew the world from having that evening of meeting people. So, I went to a lot of parties. And, for two years, Thea and I would meet at these parties and always dance together and always have people annoyed with us because we had our coats on and everyone's trying to leave — and we're dancing. But that's all. It took us a little over two years to begin to date, and then we dated seriously. And, finally, in 1967, we became engaged."

Windsor and Spyer, there can be no question, fit their parts. Photos of them from those years capture a quintessential New York City couple: elite, stylish, "in." But for the fact that they are two women, they would have been indistinguishable from any other society photos of the time.

That Windsor, raised in Philadelphia and married to a man for a short time, found that life, though, was unusual for the time. That Windsor and Spyer spent the next 40 years together until Spyer's death in 2009 — including marrying in Canada in 2007 and being the subject of a documentary film, Edie & Thea: A Very Long Engagement — is almost unheard of.

Because DOMA prohibits the federal government from recognizing their marriage and Windsor was forced to pay estate taxes on Spyer's estate at her death, however, Windsor sued. And now that the Supreme Court has decided to use her case to consider whether DOMA is constitutional, the entire country will be hearing Windsor's story.

Telling that story, Windsor even now remains focused on Spyer.

"It was a glorious life. She was a spectacular woman."

New York Democratic Rep. Jerrold Nadler, leading the House effort to repeal DOMA, says the same of Windsor. Nadler was so moved by Windsor's story that he asked her to come to Washington in 2011 to speak at the news conference introducing that bill, the Respect for Marriage Act, in the 112th Congress. "Anyone who meets Edie — regardless of their background — cannot walk away without understanding the injustice of DOMA," Nadler says. "She has lived a long full life, played by the rules, fallen in love, and embarked on a decades-long committed relationship. Had her spouse been a man, society would have rewarded Edie and Thea for their commitment and strength. Because Thea was a woman, the law has shown itself to be not only illogical and cruel, but blatantly discriminatory and wrong."

Edith Schlain finished high school in Philadelphia in 1946 as the war had ended. She, along with her brother and his best friend, Saul Windsor, started college. Already, she knew she was not like, for example, her older sister, but Schlain became engaged to Windsor nonetheless.

"I fell in love with a woman, so I broke the engagement. But, then, every New Year's, he would call and say, 'What are we doing?' So, we kept reuniting and finally…"

She and Saul Windsor married in May 1951, and she became Edith Windsor.

"I certainly did not want to be queer," she says, looking off to the side of the room while talking about an era when President Eisenhower added "sexual perversion" to the possible grounds for dismissal from public service. "There was no way. I could not imagine a life that way. I wanted to be like everybody else. You marry a man who supports you — it never occurred to me I'd have to earn a living, and nor did I study to earn a living."

What would a queer life have been?

"I had no idea what that life would have been, except underground. And denigrated. I didn't think there was anything inferior about me, but I knew that a lot of my friends would think that if they knew. And I lied all the time. My big sister knew, and ultimately became very homophobic. It was a hidden world. And Philadelphia didn't have much of that hidden world, to my knowledge."

She knew of some lesbians, women who came out of the Army at the same time that her brother and eventual husband did. "I recognized [them] as such, but even the fact of their being recognizable was another threat to me. I wasn't recognizable, so I was safe.

"Though I knew I was them, I didn't look like it."

Not looking like the few lesbians Windsor knew wasn't enough to live life married to a man, and they were married less than a year. Even that, though, proved to be difficult.

"I would see two women together on a Saturday night, and I would be jealous," she says. "I had never been out with a woman on a Saturday night, never with girlfriends even, always had dates with boys. Finally, I said to him, 'Honey, you deserve somebody who thinks you're about the best thing that could happen in the world, and I need something else.' And we split." She did tell him the reason was her attraction to women. "He was too good to not tell."

He took the news hard, but she says that it turned out for the best because he did meet a woman who fit Windsor's hopes for him, and they had children and a life together. "I didn't talk to him again for a lot of years, and he called on my 70th birthday to say, 'I still love ya.'"

Windsor left for New York City. After getting a master's degree in mathematics from New York University in 1957, Windsor joined IBM and slowly began finding her way as a lesbian in the city.

"It was before Stonewall," she recalls. "It wasn't as unknown as everyone would have you believe, so Stonewall wasn't really the beginning, but it was a wonderful rebellion. Until then, people who wanted to march and protest did it very carefully in proper suits and ties, and the women dressed in dresses. You were asked to leave if you hadn't come dressed properly. But, they existed. And they cared."

Then she met Spyer at Portofino, and everything changed.

"We fell in love," she said, with eyes that mist over even now when describing that first night. "I had believed until then, I truly believed, that if you're a lesbian and you don't meet someone when you're an undergraduate, forget it, there's nowhere in the world you could find someone. And I truly believed that. I still didn't believe it until I met Thea, when I was then determined to make a life.

"My mother filled my head with romanticism. And I thought I would never have that. My sister would have it, but I would never have it. And all the sudden I had it all the way. It was always extremely romantic. I don't know what else to say."

After being together for 13 years, the couple were deeply in love but faced a challenge that would dominate much of the rest of their life together: Spyer was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, a disease that eventually left her body confined to a wheelchair — but never touched her mind.

"I watched her," Windsor said flatly. "She kind of reinvented herself every year, every year the paralysis extended and got worse. She was always very alive, she always had this very alive personality."

Windsor told the story not as a story of decline, but as a part of their love story — and of how Spyer kept very much alive during those years. The stories of their life together also inevitably intertwine with a story of gay history.

"Even through the '70s, men couldn't dance together. There couldn't be only men dancing on the dance floor, so there was always a woman present. That's how the line-dancing became the thing for eight years, ten years almost. Still, primarily, in bars off the highway, in the Hamptons, for instance," she says. "And suddenly it changed, and men could dance together, and the off-the-highway places were closing. By then, Thea had no balance, so she was on two Canadian crutches. She could lead with her weight on the good leg. She could get on the dance floor, drop the crutches, and dance. We never danced together that we weren't at some point yelling, 'I love you. God, I love you!'"

By 2002, Spyer was diagnosed with a cardiovascular condition called aortic stenosis. At that point, Spyer was quadriplegic and got around by using an adjusted mouse to maneuver her wheelchair. "Her decision was not to have surgery, and I agreed with it. [S]he was on hospice for a long time because she qualified in every way, and she beat it. So, she became kind of, their poster girl."

The MS kept progressing, though, despite the temporary victories. Spyer started having trouble breathing as the paralysis moved in on all of the muscles that go into breathing. She was given a year to live. That prognosis, though, led to the wedding.

"I had asked her previously," Windsor said. After marriage equality efforts failed in New Jersey and New York, "I had asked her, did she want to go to Canada? And she said, 'Not really. I'll do it if you want it.' And there was no way I was going to drag her if she didn't passionately want it. But then, when she got this prognosis, she got up the next morning, she said, 'You still want to get married?' And I said, 'Yes!' She said, 'Let's go!'"

On May 22, 2007, Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer were legally married by Canada's first out gay judge, Justice Harvey Brownstone.

"I ask all gay couples who have lived together a long time and got married, 'Was it different the next morning?' And everybody says yes, and they don't know how to explain it. Marriage itself, you know, it's a magic word, everybody knows what it means, it means love and commitment and trust and stuff — but there's this extra thing when it was always denied to you. But it's profound. Whatever loving was there, it becomes really profound loving."

As Windsor had suspected, however, their time together was nearing its end.

"She asked me if she was dying. And I said, 'I think so, honey, very gradually. Probably I am too. We're old ladies.' But she knew. And I knew."

On Feb. 9, 2009, Thea Spyer died.

"In a sense, she died in time. If she had lived until she lost that last thing and lost all kinds of connection and lost being able to take herself anywhere —" Windsor trails off. "So, it was good. It was the right time. It's hard to live with still. It's three years, and it's — I say, 'It's fine, OK, I'm me,' and I'm not at all."

Windsor suffered a heart attack a month later, but recovered enough to be able to attend screenings of the documentary about her landmark relationship. "I was totally with her all the time, in the film. So, that didn't give me a chance to really mourn, maybe, 'til later."

Windsor didn't only have to deal with Spyer's death, she was also was forced to pay more than $350,000 in federal estate taxes because the federal government didn't recognize her marriage to Spyer.

"I knew it would happen, I never dreamed it would be that high," Windsor says. "They took any gifts that she had given me over 40 years, became part of her estate again, and I paid 50% tax on those things. I did want to sue the government. New York State accepted my marriage, in which case I thought the federal government should. I had already been active in equality and marriage organizations. Then Robbie Kaplan, who walked into my life."

Kaplan, a partner at Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison, has a past with marriage cases. She argued to the New York Court of Appeals in 2006 that the state's constitution required that same-sex couples be allowed to marry. Though unsuccessful, she says there's "no question" that the case paved the way for the state's lawmakers to pass a marriage equality bill in 2011. "Without losing in the court of appeals, the legislative victory probably wouldn't have happened.

"What that said to me, and I think it should really be a lesson to others, is that if you have a really good case and you've been treated unjustly, then there's no reason not to bring that case," says Kaplan, who herself is married to a woman and is raising a child.

When Windsor came to her with the case, Kaplan says the facts and the law were so strong that she didn't hesitate. Filing the case in Nov. 2010, the Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders already had succeeded at the trial-court level in challenging DOMA's federal definition of marriage in a case brought on behalf of several plaintiffs denied benefits because of DOMA. Karen Golinski, a federal court employee in California, was challenging her denial of equal health insurance benefits for her wife. And, on the same day that Windsor and Kaplan filed their lawsuit in federal court in New York in partnership with the American Civil Liberties Union, GLAD filed a second lawsuit challenging DOMA in federal court in Connecticut.

On Dec. 7, 2012, the Supreme Court announced that, of the four cases, it had decided to hear Windsor's case.

Evan Wolfson, the founder of Freedom to Marry, has been a leading architect of the marriage equality movement and has seen hundreds of same-sex couples — and has made it an aim of Freedom to Marry to tell their stories. Windsor knocks him off his feet.

"Her story is compelling in so many ways: the journey it traces through gay people's movement to acceptance and openness, the decades of commitment she and Thea showed one another," he tells me. "The depth of their love, the struggle with illness, the work to be there for each other, getting married and being able to have a marriage — something they may never have dreamed of when they first met and began their life journey together."

He's also looking at the nine justices who will determine the outcome of her case — and whether other same-sex couples will face the impact of DOMA in the future.

"Edie is a perfect person to stand before the Supreme Court and the country with a powerful story and a beautiful smile, showing the massive injustice and unfairness of disrespecting the marriage and commitment she had with Thea and the wrong of denying a senior citizen important legal and economic protections that come with marriage."

Kaplan, in personal terms that reflect the friendship that she's formed with Windsor over the course of the past two years, lays out the argument against DOMA's constitutionality in simple terms: "When a very significant percentage of the population live in states where gay and lesbian couples can marry, it's just intolerable to have a system where couples are married for purposes of state law but not married for purposes of federal law and who, in all practical effects, are being treated like second-class marriages. And that's essentially what our case is all about, and I think the court will agree."

Windsor, for her part, continues to remain confident as well.

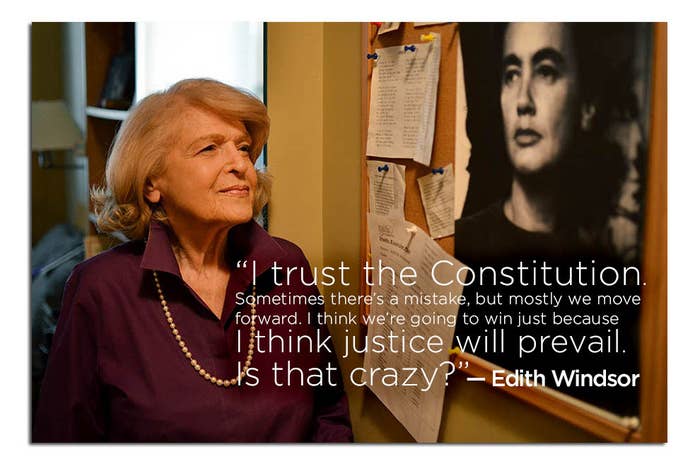

"I was the youngest kid in my family, I got this passion for justice and I grew up with that, so fourth-grade civics thrilled me," she says. "There's a whole world of justice. And so, I'm not skeptical, like a lot of gay people of my generation. I trust the Constitution. Sometimes there's a mistake, but mostly we move forward. I think we're going to win just because I think justice will prevail. Is that crazy?"

They look at each other and smile, a moment that recalls the overcast day in September when they spoke to reporters after the hearing in their case before the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals. "I look forward to the day when the federal government recognizes all marriages as legal," Windsor said then, "and I'm very hopeful that that day will come when I'm still alive."

She now plans to travel to Washington in March to watch Kaplan argue the case before the Supreme Court.

"The idea that I might be a piece of history blows my mind. I think it's kind of wonderful that I'm getting my chance to really ask for justice, and I suspect I'll get it. I'm still that little kid from the civics class. And I think they're going to rule in our favor because I think that's just."

Photographs by Macey J. Foronda for BuzzFeed