WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court justices wrestled on Monday with the question of when a judge has to recuse herself or himself from a death penalty appeal and to what extent that decision is required by the Constitution.

The case involves the 1986 death penalty trial of Terrance Williams — convicted for the murder of a man who Williams' co-defendant later acknowledged had sexually abused Williams — and the subsequent appeal of the death sentence imposed on Williams.

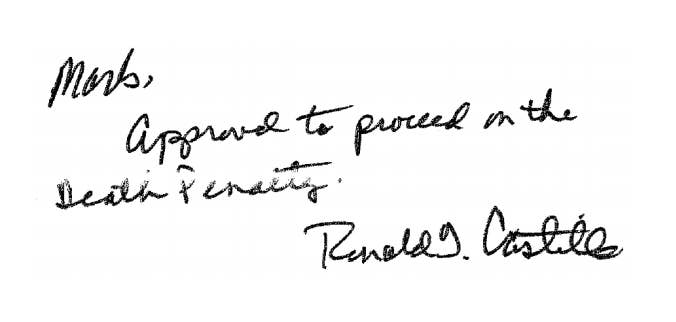

At the trial, Ronald Castille was the new head of the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office and personally signed off on the decision to seek the death penalty. When the appeal at issue reached the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decades later, Castille was the chief justice of the court and refused to recuse himself from ruling on the case. (He has since retired.)

The question before the U.S. Supreme Court justices on Monday was not, specifically, whether Castille should have recused himself from hearing the appeal — most of the U.S. Supreme Court justices hearing the case on Monday seemed to think that he should have recused himself. The question was whether his decision not to do so violated Williams' constitutional rights to due process and against cruel and unusual punishments.

The main issue up for debate in the arguments was exactly what test Williams' lawyers wanted the court to apply going forward for judging whether recusal decisions violate defendants' constitutional rights — and whether there was any test going further than current law that the government (the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office) would consider acceptable.

The majority of the court appeared uncomfortable with a ruling that would bless Castille's participation in the case, but it was not clear how the justices — particularly Justice Anthony Kennedy — would draw the line in the case, and how they would do so.

The Philadelphia District Attorney's Office, citing prior Supreme Court cases, argued that recusal is only required when facts, under the totality of the circumstances, raise "the probability of actual bias" in the case.

Williams' lawyer, Assistant Federal Defender Stuart Lev, argued that the court should either go further and/or "clarify" that its earlier ruling would include required recusal where a judge had direct personal involvement in the case in her or his prior role as a prosecutor and where the appeal issue relates to that prior involvement.

The government's lawyer, Deputy District Attorney Ronald Eisenberg countered by saying the standard suggested by Lev would be unworkable because it ignores that judges are "human beings" with prior lives.

Justice Anthony Kennedy, who wrote the 2009 decision cited by Eisenberg, questioned his argument, noting that an amicus, or friend-of-the-court, brief in the case filed by former judges who had prosecutorial experience signaled that ethics rules and the federal recusal statute show that such standards are not unworkable.

Kennedy was also suspicious of another argument Eisenberg pressed repeatedly. The Philadelphia government lawyer argued that the significant time that had passed since Castille had been involved with the case meant it was less likely that there was a significant risk of "actual bias."

Kennedy balked, asking of Williams' time on death row, "So, the fact that he spent 30 years in solitary confinement helps the state?"