Can something as mundane as a photo-sharing service predict the weather? According to a team of British scientists: maybe!

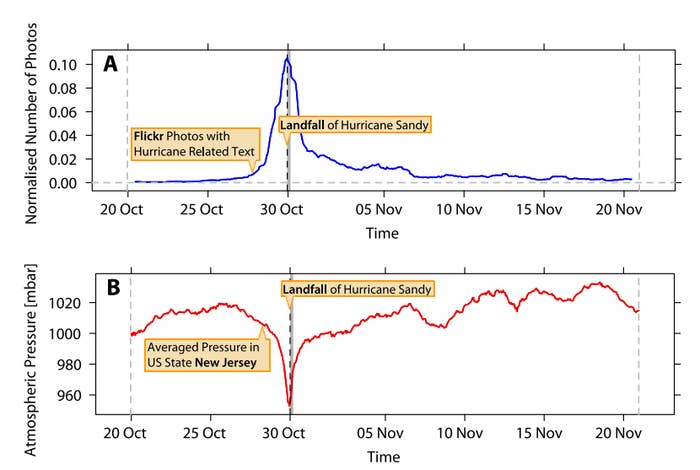

In a new study, researchers from the University of Warwick tracked Flickr photo uploads in the days before and after Hurricane Sandy made landfall — specifically, the number of pictures with tags for "Hurricane Sandy," "hurricane," or "sandy" between Oct. 20 and Nov. 20, 2012 — and found a "striking correlation between the moving average of the normalized number of Hurricane Sandy related Flickr photos taken and the atmospheric pressure in New Jersey."

While plenty of external factors, such as media coverage in anticipation of landfall, could certainly draw attention to the storm and contribute toward increased upload rates, Flickr does appear more immune to media hype than other news-focused social networks like Twitter, Facebook, and even Instagram, where most news outlets have built-in followings and news sharing is normal. Flickr is typically used for original uploads — photos and videos taken by users — not re-shared media.

In Sandy's case, the correlation between uploads and the intensity of the storm was direct enough to suggest that, "in cases where no external sensors were available, it may be possible to measure the number of Flickr photos relating to a topic to gauge the current level of this category of problems."

While Flickr and its large network of dedicated amateur and professional photographers might be a truer gauge for measuring the local severity of events like Sandy, it's not the only photo service that proved its value during last year's superstorm. Instagram users uploaded more than 10 photos per second during Sandy's peak and proved to be an invaluable asset for news outlets looking to grab real-time updates from the ground.

It's a short and unrefined study, but hints at an exciting, if obvious, possibility: that our social inputs during major national events may be useful in tracking and measuring the severity of a given event. After all, what could be a better indicator than hundreds of thousands of individual, independently produced reports straight from the source?