AUSTIN — It was the winter of 1997 and Alex Jones couldn’t stop getting punched in the face.

Out on the cracked asphalt of Austin Public Access Television’s parking lot, under the sprawling Texas live oaks, Jones was very much losing a fight to a man known affectionately in Austin’s alternative media scene as "SpaceHitler."

According to multiple reports and interviews with two eyewitnesses, for months, SpaceHitler — real name: Clayton Counts — had been prank-calling Jones’ largely unsuccessful public-access TV show and mocking the exasperated host as "Jarhead Jones" until his call was disconnected. On this particular day, Counts and a gaggle of friends showed up to an ACTV open house with the intention of taunting the 22-year-old host in person.

According to one witness, Counts’s crew traded insults with Jones for a few minutes until one of Counts’s friends started back in with Jones’ least favorite barb: Jarhead.

That’s when Jones asked them to “step outside.”

It's not entirely clear just what happened next — a police report tells only Jones’ side of the story — but witnesses to the brawl said the broadcaster bolted to his car, rummaged under his driver’s seat, and mimed tucking something in the back of his waistband while muttering about using a gun for self-defense.

"Go ahead and shoot me," one of Counts’s friends said, before knocking Jones square in the face with a surprise haymaker.

“Alex tried to fight back but was throwing wild punches with no form,” one witness, Charlie Sotelo, said recently. “The guy is no fighter.”

Eventually, someone called the police. Counts and his friends left before they arrived. Sotelo stayed behind with a bleeding and increasingly belligerent Jones, who was pacing back and forth, raving about “counterculture Generation X types” and spinning up the sort of conspiracy-soaked rant that would decades later make him famous and rich. “Alex is hopped up on adrenaline and he couldn't compose himself,” Sotelo said. “He's claiming to everyone there are more people than there were and that one of them had a knife. Total lies.”

Sotelo — who'd so far managed to stay out of the scuffle — told Jones he was full of shit. Jones kept ranting, the blood from his busted lip misting onto Sotelo's brand-new shirt. Jones threw a punch and missed; Sotelo threw a punch and did not. Police soon had to separate the two, leading Sotelo back into the studios.

“When I came out, Jones was unhinged,” Sotelo recalled. “He just can't help himself — he can't shut it off and he starts yelling at the police." At some point, Jones' father showed up. He calmed his son down and wrote Sotelo a $100 check for the ruined shirt. (Sotelo later gave the shirt away on his own public-access show: “The joke was that you could use the dried blood to clone Alex,” he said. “It went fast.")

“He just can't help himself — he can't shut it off."

In the end, no one pressed charges. Later, when he spoke about the incident to a local reporter, Jones first suggested he’d been the one who was attacked, and then denied the incident ever took place. In a statement to Austin Police Detective Dusty Heskew, Jones said he was unfairly “taunted” by four to five men, one of whom had “eyes that look like a goat’s...and pasty white green skin” and wielded “a double edged military type killing knife.” According to Jones, Counts was dangerously “obsessed” with him. “I am not an easy person to scare, but I believe that he bears me incredible malice,” he said at the time. “I am in fear of losing my life.”

Though that statement predates by decades the Infowars media empire Jones would later create, it now looks like an early playbook for his wildly successful libertarian- and conspiracy-news juggernaut: Take a kernel of truth, warp it and its context in a funhouse mirror, and set it against a heavy backdrop of conspiracy, while raising the stakes with a generous dose of fear. The strategy has made Jones — a stocky central Texan with a penchant for clamorous outbursts, fanciful digressions, and meandering stream-of-consciousness monologues — a celebrity. It's also made Infowars — his broad kingdom of media properties, including a website, webstore, and four-hour daily broadcast — a required part of the far-right's media diet.

In 1997, it was a statement to Detective Heskew. Post-9/11, it became a daily broadcast to an audience of millions with a singular message: There’s an imminent war for your mind. Evil, powerful forces have rigged the system. And Jones — blustering, outrageous, utterly captivating — is the one who will stop it, if only Americans would wake up and stop dismissing him as a jester.

After two decades, they have. Jones has today found a place in a United States he helped create, led by a president he helped push into office. From the beginning, Donald Trump was a human distillation of Jones’ anti-establishment, anti-globalist, pro-libertarian, massively paranoid worldview; Jones, meanwhile, was an enthusiastic messenger for Trump’s campaign. There was Trump’s appearance on Jones’ show, in which he praised the host’s reputation as “amazing”; Infowars’ “Hillary for Prison” T-shirts, ubiquitous at campaign rallies; Jones’ championing of WikiLeaks’s emails dump and his characterization of Hillary Clinton as, among other things, “a complete wanton power-tripping self-worshipping devil worshipper”; and finally, in the earliest hours of November 9, a tearful Jones outlining Trump’s plan to “build a better world” while clinking champagne glasses with Trump adviser Roger Stone and listening to Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.”

After 15 years of obscurity, Jones has the audience and the influence he always wanted. And yet he is, somehow, off his game. He spent the first 100 days of the Trump administration — what should have been the honeymoon period — apologizing for his role in promoting the "Pizzagate" conspiracy theory, retracting his claims to stave off legal action, and, perhaps most unexpectedly, trying to convince a jury that some of his most salacious on-air diatribes were really just "performance art" all along.

Jones, an unwavering professional conspiracy theorist, is being interrogated about his true beliefs just as his golden age of conspiracy is ascendant. But conversations with 25 people in Jones’ orbit indicate that his troubles don’t stem from a split between the character and the human, but from the fact that Jones is eminently and unquestionably himself at all times. Jones has been this way since he was brawling among parked cars. It’s made him a fortune, but now that his moment is finally here, it could be his undoing.

The son of a homemaker and prominent dentist, Jones moved from Dallas to Austin as a teenager. In the early '90s, the city was a dirt-cheap home to artists, musicians, and zine makers living in an estuary of bohemian and honky-tonk influences. It was, according to Shannon Burke, a local talk-radio host, “the perfect incubator for him. It’s that libertarian and weirdness blend that wouldn’t have worked had he been born in Milwaukee.”

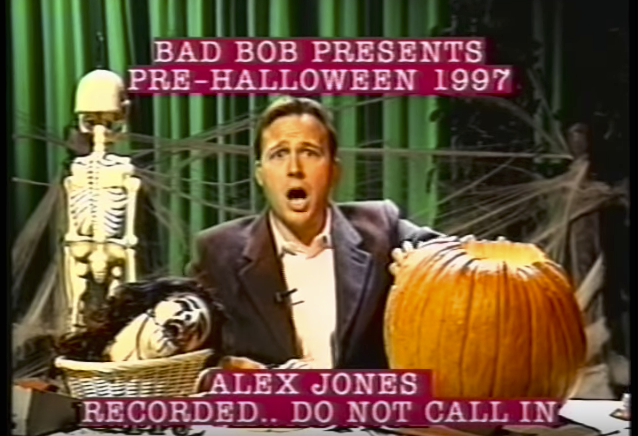

And nowhere was that weirdness better showcased than Austin Public Access, the TV station where Jones got his first big break. In the '90s, ACTV “was wild and unmoderated — like the YouTube of its time,” Brian Blake, the station’s longtime producer and IT director, explained. For Jones, then just out of high school, it was a huge opportunity — a chance to spend an hour in front of a camera saying pretty much anything he wanted to Austin’s night owls.

From his first broadcast, Jones targeted the threat of the New World Order, which he had first encountered in the book None Dare Call It Conspiracy, discovered on his father’s bookshelf. His earliest monologues were stark and raw; Jones would deliver his homilies from a bare table, surrounded by stacks of newspaper and often fumbling with his words. But the message and the intensity were indistinguishable from the Jones on the air in 2017.

“He just walked into the booth, sat down, and started in on a rant cold — I never saw anything like that.”

Jones was a modest public-access success, but he owes his first real media job to his dentist father, who solicited a station manager at the Austin talk radio station KJFK during a routine teeth cleaning. “He said, ‘My son’s got some out-there ideas but I think he’d be perfect,'" Daryl O’Neal, the KJFK manager who brokered the deal, explained. "The next week he brought Alex in for a meeting." To secure Jones a spot on the station, Jones’ father became his son's first on-air advertiser.

Jones was a natural. “He just walked into the booth, sat down, and started in on a rant cold — I never saw anything like that,” Ryan Schuh, Jones’ former studio engineer, said of his first broadcast. Other early coworkers said that Jones’ famous, and often disorienting, theatrics have been there from the start. Burke described a moment when a caller attacked Jones on air as a soft, buttoned-up media type. Jones, according to Burke, erupted into tears, yelling, "My name is Alexander Jones and I played football, man, and my parents are still married and I'm a damned American!" The caller was stunned.

“We went to break right after that, and he puts his head in hands and is rubbing his eyes all sheepish,” Burke recalled. “He turned to me and said, ‘Was I crying too much? I just turn it on sometimes and I don't know how to stop!'”

Jones wouldn't confirm or deny this anecdote, or any others. He responded to BuzzFeed News' list of questions with a short statement: “Most of the information below is pure fiction.” Pressed for clarification, he offered this: “Make up what ever you want, don't use me as a prop in your piece to pretend its not fiction.”

On a sweltering, cloudless morning last month, Jones sat in a stuffy third-floor courtroom watching the persona he’d spent two decades building stand trial. He was fighting for custody of his three children in what would be a grueling two-week ordeal, and his lawyers were making the case that Jones' 20-year career propagating outlandish conspiracy theories shouldn't be considered an indictment of his parenting skills. It was "performance art," and nothing more. A typically ordinary matter of family law had thus come to hinge on a more extraordinary question: Where does Jones the character end and Jones the person begin?

Jones’ lawyers argued, essentially, that there are two Alex Joneses: the staid family man and the professional provocateur. But over nearly 10 hours on the stand, the testimony of Jones the man revealed a volatile, restless, and sometimes charming personality that closely resembled the Jones that presides over Infowars’ video and radio broadcasts.

A typically ordinary matter of family law had come to hinge on a more extraordinary question: Where does Jones the character end and Jones the person begin?

Jones shifted in his chair like a child enduring a long sermon, his round, deeply expressive face a cartoon reel of exasperation and incredulity. Many of Infowars’ greatest hits made their way to the court record: Questioned about his marijuana use, Jones denied being a regular user, claiming he simply tests the drug yearly “to monitor its strength like law enforcement does." (He also blamed billionaire political donor George Soros for increasing its potency.) Later, during a brutally personal line of questioning about his sex life, Jones erupted. “You have just no decency — how you spin this — I’ve never seen anything like it on TV or in movies,” he bellowed.

“Do you think that’s an appropriate way to behave in this court, sir?” the opposing attorney countered.

“It’s been said before in federal court — ‘Have you no decency?!’” Jones shot back through gritted teeth.

It was a perfectly Jonesian moment: earnest but performative, nakedly emotional, and completely courageous in its conviction, no matter the cost. As is usually the case when Jones takes the floor, the room was rapt.

People who worked with Jones during his early career describe him as perpetually "on" and ceaselessly focused on rooting out conspiracy of all kinds. “It was 24/7,” O’Neal recalled. On days when the crew would gather at a house or bar after work, Jones would sometime show up with a pile of documents in tow, touting it as evidence of some globalist threat. “He’d come over and go into his spiel and we’d tell him to be cool and he'd yell, ‘THIS IS SERIOUS STUFF,’” Matthew Hobley, a KJFK employee, recalled. “We’d be like, ‘Damn, Alex, it’s our day off.’ But he’d go and go and by the time he was finished there were papers everywhere.”

Others who knew him at this time remembered Jones as volatile, easily bruised, and prone to vengeance. One associate recalled Jones tearing down bulletin board memos from fellow station producers who’d criticized one of his more controversial segments. And an Austin Chronicle article from July 2000 cites multiple public-access producers who claimed “that Jones has used both ACAC policy and legal maneuvers to intimidate them or get them thrown off the air.”

“Being on TV or radio has a way of changing you,” Austin Chronicle founder Louis Black, an early Jones critic and frequent target of Jones’ early rants, said. “And for Alex it was always, always about ego. When he got that validation, there was no going back.”

Jones’ current success comes from a calculated tornado of constant promotion, limitless content, and healthy willingness to sacrifice facts for narrative. Those close to him describe a good Alex Jones monologue with the admiration generally reserved for a work of art, his meandering diatribes as evidence of a kind of V8 engine of a brain that’s capable of cobbling in vague historical references and conspiratorial buzzwords to masterfully link a story about, say, Amazon delivery drones to FEMA concentration camps in three easy steps. A former producer marveled at his ability to take the headline of a story placed on his desk and, without reading it, expound on it for half an hour on the air.

“Sometimes he'll say he has sources and he's been told a piece of news has been confirmed but we wouldn’t have that information,” a former Infowars employee said. “Later we’d find out it was because a week earlier we had a caller on air who theorized about something and Alex repeated it as fact.”

When he’s at his best, Jones moves seamlessly between faux outrage and puckish, contagious excitement; he is somehow both more serious and having more fun than anyone else. He frames his broadcasts as small rounds in an endless fight for the survival of liberty, and repeatedly involves his viewers as fellow warriors in the fight for truth.

“He really modeled everything off of the televangelist networks and their knack of using trust and faith to market things,” a former senior employee of Infowars said.

Jones won that trust via a series of documentary films during the mid-aughts. Most notably, he is credited as a producer of the 9/11 truther documentary Loose Change, which exposed an entire generation to the idea that jet fuel can't melt steel beams and made Jones a viral phenomenon long before YouTube.

Around that time, Infowars became defined by an ideology of opposition: to fluoride in the water, to the World Bank, and to mindless pop culture icons like Justin Bieber, draining ambition from America’s youth. Jones’ skepticism is bipartisan: During the Bush years, Infowars raged daily against growing federal government, torture, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and warrantless spying — but then, in the first months of Obama’s presidency, Jones popularized the viral image of Obama as the Joker. In March 2009, he released The Obama Deception, an ominous two-hour documentary in which he depicted the new president as the greatest threat to “the hope of free humanity.”

The Obama presidency — and concurrent rise of birtherism, the tea party, and what would later come to be known as the alt-right — was an unqualified boon for Jones and his empire. “We were getting more and more calls from people who seemed unwell claiming that the FBI was watching their house,” one employee said. “We kept saying 'We’re the underdogs’ — that was our mantra. But it slowly started to feel more like we were becoming the majority.”

Jones was riding high — and former Infowars employees told BuzzFeed News that when times are good, Jones’ manic side tends to come out. “He’d run around yelling, ‘You get a bonus! We had a huge sale day!’” a former employee recalled. Another staffer recalled an elated Jones calling staff to the Infowars warehouse, where he grabbed a bow and arrow and began gleefully shooting at boxes of DVDs and shirts.

“He just kept saying, ‘Oh my God, if Obama loses, we're out of business.’”

But others close to Jones during this time said that despite a growing audience, the broadcaster was insecure. Two former colleagues said Jones reserved his greatest resentment for Rush Limbaugh. The jealousy was so intense that Jones began to crib his now-famous crushed gravel voice from the talk radio legend. “We'd spend weeks getting everything just right in the studio,” a former employee recalled. “Then he'd go for a drive and hear Rush again and say, ‘I need my voice to sound something like that.’ And so we'd completely re-engineer the sound to make him gruffer.”

Former Infowars employees suggested that Jones’ secret fear was that his opposition would someday run out — especially if Obama lost re-election. One recalled Jones pacing back and forth on Election Day in 2012, nervous over the prospect of losing the polarizing president that had helped usher in ratings gold.

“He just kept saying, ‘Oh my God, if Obama loses, we're out of business,’” the employee said. “One of the guys in there asked, ‘You didn't vote for Obama, did you?’ And Alex said nothing. Just a grimace. I don't know what it meant.” A member of Jones’ staff during the 2012 election speculated that he would do anything for the sake of his show. “I personally think he voted for Obama to keep ratings going,” another former employee said. A third employee recalled Jones dropping hints that he was planning to cast his vote for Obama.

Obama did, of course, win, and Infowars rode the wave to even wider success. By 2013, the site was propagating many of the most enduring ideas of the conspiracy-theory internet: that nefarious forces are spreading biological weapons via chemtrails, that the government controls the weather, that the Sandy Hook massacre was a hoax, and that Bill Gates is the leader of a eugenics plot to rid the world of minority ethnicities.

Kate Starbird, a professor and researcher at the University of Washington, accidentally stumbled upon Infowars’ digital footprint while conducting a study of how rumors spread on Twitter during the 2013 Boston Bombing. Starbird found that a specific rumor — that Navy SEALs had carried out the attack — was largely attributable to Infowars’ tweets and links, second only to YouTube. “At the time we thought it was pretty insignificant,” she said. “But things look different in hindsight.”

As Jones’ sphere of influence grew, so did his business. In 2013 the Infowars store — which launched in 2006 selling T-shirts, Jones’ documentaries, and a few prepper goods — was reborn as Infowars Life, a one-stop shop for the modern conspiracy theorist. Each product fits cozily into the Jones narrative. Concerned that the globalist cabal put fluoride in the water to make Americans sick? Infowars has you covered with a $14 anti-fluoride toothpaste. Worried that government-mandated pesticides are slowly draining you of vital nutrients? Pick up some Secret 12, a $29 vial of liquid B-12.

“When the Fukushima nuclear disaster happened, Alex bought tons and tons of potassium iodide and oh my god, did we sell that,” a former employee recalled. “He can sell 500 supplements in an hour,” another countered. “It's like QVC for conspiracy.” Infowars Life now sells a full battery of supplements purporting to solve a vast spectrum of problems, real and imagined; items include Super Male Vitality serum, Brain Force Plus, and Caveman, a $60 mix said to help Infowarriors “rediscover the human blueprint, and experience the power of cutting edge science.”

“He can sell 500 supplements in an hour. It's like QVC for conspiracy."

The supplements, according to multiple former Infowars employees, completely transformed Jones’ burgeoning operation into a media empire. According to one former employee, Jones bragged that the Infowars store grossed $18 million between 2012 and 2013. Another source puts that number closer to $10 million — and this was before the popularity Jones and Infowars enjoy today. Part of the success of the store came from Jones’ ruthless deal-making. “I watched him on the phone with some poor author who’d written a book Jones wanted to buy, and Alex would negotiate him down until he's making no money,” Jack Blood, a former radio colleague, said.

Two former employee alleged that Jones would instruct staff to find products that were failing and convince them to whittle their margins to almost nothing in exchange for the Infowars endorsement. “Alex’s business model was to ensnare these companies at a low rate, and lock in exclusivity,” the former staffer said, noting that attaching the Infowars brand to a product often destroyed a seller’s future prospects to go mainstream. “I’ve seen him undercut a company that sells survival straws for $25, force them down to $10, and sell them at $50,” another former employee claimed.

For some employees, the shift from what they saw as crusader journalism to content marketing for colloidal silver was jarring. “It became a moral issue for me,” one said. “It’s why I don’t work there anymore.”

And then there were the Infowars’ “money bomb” telethons — marathon events to raise money for the for-profit institution. Three former employees told BuzzFeed News that a money bomb could easily raise $100,000 in a day. “People were just so taken by the information we’d been pushing they’d do anything,” an employee said. “It made me sick to my stomach,” another said, recalling a donor who charged a donation to her credit card because her house had been foreclosed. “I'm convinced after working there that fear sells as well as sex. Judging by his profits, maybe it sells even better.”

Four former staffer suggested that this influx of money inspired the greatest change in Jones’ demeanor, and in Infowars’ strategy. “It’s became less about effecting change and more about being sensational and making money,” one ex-employee explained. “It didn’t start out that way. He was a lovely person to hang around for a long time, but soon that evaporated.”

Another employee saw a similar change in Jones’ personality. ”When I started Alex was a very different person. He had the core elements of what you see today, but he was enjoyable to be around. He had the volatile side but it wasn't only volatility.“ In interviews, four separate employees — unprompted — described Jones as a “tyrant” who oscillated manically between excitement and anger. “Working for Alex was like a combination of Blackbeard meets Hitler,” one former employee said. “One minute just on a high and swashbuckling and calling us to action; the next, punching out walls.”

The Infowars office fell largely into two camps: those who bought fully into Jones and the information-war narrative, and those who were less sure. For the inner circle, Jones was not just a boss but a mentor, friend, and compelling leader, treating favored employees to meals at a Brazilian steakhouse chain called called Fogo de Chão. “He’s so magnetic that no matter what happened I couldn’t bring myself to hate him,” one said. “It was the highest-energy, most stressful job I’ll ever have, and I dislike a lot of what we did there, but don't hate the guy. I really can’t explain it.”

“Working for Alex was like a combination of Blackbeard meets Hitler.”

But Infowars staffers not part of Jones’ inner circle tell a different story. “It was a brutal environment,” one recalled. Another told a story about Jones firing an editor without telling him. Instead, he told the office the editor had quit, and left it to his staff to pick up the pieces when the guy came to work the next day for a job he no longer had.

Two former employees recall that, after an employee left the company, Jones would call a staff meeting, pull up YouTube videos of their work, and take turns making fun of them. “The unsaid implication,” a former employee said, “was that if you leave, this will happen to you.”

“Jones rewards the people who buy in all the way,” one former employee said. “But there's an expectation not to contradict him or the message.”

Those long departed from Infowars see a through line from the tumultuous atmosphere inside Jones’ office around 2013 to the xenophobic, pro-masculine, anti–social justice tone of today’s Infowars site and broadcasts. The site, after all, was a business, and Jones a salesman eager grow his base. And in 2015, when Donald Trump rode down his gilded escalator in Trump Tower to announce his candidacy for president, Jones made what is arguably the most consequential investment of his career.

Talk to enough people who know Alex Jones and a clear portrait emerges. Dozens of interviews reveal him as distractible, prone to foul moods, fiercely loyal until crossed, and extremely vindictive. Someone whose outward confidence has a kind of gravitational pull, and who thrives in the spotlight. A guy who’s thin-skinned but constantly picking fights. A man obsessed with advancement of the brand he’s been building since long before anyone took him seriously. You get the sense that he truly is a singular human being. That is, until you recall Donald Trump.

Jones entered Trump’s orbit through longtime political operator and unofficial Trump campaign staffer Roger Stone. Stone and Jones met in 2013 at a conspiracy theorist event marking the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination. The two took to each other instantly. In Jones, according to a mutual acquaintance of the two men, Stone saw a like mind, with a hair trigger for conspiracy and a wide reach. And in Stone — again according to a mutual acquaintance — Jones saw an opportunity to become central to the news cycle instead of proselytizing at its fringe.

“He's like the Goebbels of 2016. He really won the election for Trump."

Stone introduced Jones to Trump, and the rest is history. According to one person present at Infowars’ studio on election night, Jones boasted of having 18 million viewers as the returns came in. “Now, Jones is probably exaggerating,” the source said. “But if it’s even half that, you’re talking serious influence if you can get them voting. Alex doesn't have listeners — he has followers.” The audience Jones had spent decades building had finally made its presence known — at rallies, on social media, and, finally, at the polls. “That rural vote for Trump nobody saw coming?” the source continued. “It wasn’t only Alex, but I think you can ascribe a significant portion — many first-time voters — of those votes to him.”

“He's like the Goebbels of 2016,” another longtime Jones associate said. “He really won the election for Trump.”

As of now, Trump’s relationship to Infowars is unclear. Three sources close to the Trump campaign and the Trump White House say they haven't heard Trump mention Jones or Infowars by name beyond that December 2015 interview. Trump does not, according to two of these people, receive Infowars articles in his daily media clippings. Asked if Jones and Trump ever speak privately, all three say they’re not aware of any communication, but caution that they can’t be sure.

Jones himself seems to confirm this. Approached on the steps of the Travis County courthouse on a humid March afternoon and asked when he last talked to President Trump, Jones offered a terse reply: “We don’t speak much since he became president.”

Not that it matters. Jones’ influence still makes it to the White House via the conservative media food chain, which frequently aggregates and propagates Infowars stories. In early March, in response to claims that the Trump administration was potentially colluding with Russia, an Infowars editor tweeted an old photo of New York Sen. Chuck Schumer looking chummy with Vladimir Putin. Twelve hours later, the image was splashed atop the Drudge Report, and less than 12 hours after that, Trump’s presidential account had tweeted it. It wasn't the first time something like this had happened. In November 2016, Infowars published a story citing an unverified claim from a former Texas Health and Human Services Commission deputy commissioner that 3 million noncitizens voted illegally. The Infowars story was linked by the Drudge Report and, 13 days later, wound up the subject of a tweet from Trump’s account. As Jones put it last summer to the journalist Jon Ronson, “I put out a video. A message to Trump, and then two days later he lays out the case. It’s like sending up the bat signal.”

On November 9, mainstream America woke up to the contours of an honest-to-god information war. Alex Jones named his company after it in 1998. He is an architect of our current political moment, and yet he looks miserable.

As one staffer tells it, behind the scenes, Jones was far from elated on election night. “He looked depressed,” the staffer said. “You could tell when he found out that Trump was going to win. You could see his mood change.”

After all, the staffer said, “his business is based on a fear of the left taking over a conservative way of life. He has to have that power of fear — that idea that 'they're gonna take your guns.' Trump winning put it all in jeopardy."

After a career spent crusading against the establishment and the elite, Jones is now an insider. He’s traded in the frumpy T-shirts for nice navy blazers. During his divorce, he rented out the lavish penthouse of one of the nicest high-rise condo buildings in downtown Austin. One former employee described him recently as “now enjoying the finer things.”

“His business is based on a fear of the left taking over a conservative way of life. He has to have that power of fear — that idea that 'they're gonna take your guns.' Trump winning put it all in jeopardy."

For the first time, Jones’ rants are being carefully examined and picked apart for inconsistencies, his empty threats tallied and reported. Just this year, Jones has been beset by controversy and scandal that suggests maybe he’s built himself a movement that he can no longer control. And those close to him say that in recent months, Jones’ theatricality has taken on a darker, more violent tinge.

After Alec Baldwin appeared as Donald Trump on Saturday Night Live in a skit in which Jones was mentioned, he threatened to break the actor’s jaw, nose, and neck before exploding into maniacal laughter. “My fists are going to be bleeding with your teeth marks all over them,” Jones snarled before screaming “I hate you!” And earlier this month he broke his "family friendly" rule on the air, referring to Democratic Congressman Adam Schiff as a “fairy” and “the archetypical cocksucker...sucking globalist dick.”

An early champion of Pizzagate, Jones later embarrassingly walked back his statement under the specter of legal action. In April, the yogurt company Chobani sued Jones for defamation, alleging that he published false information and reports about the company’s involvement in a sexual assault case in Idaho. Both legal scuffles represent the type of reckless punditry and pseudo-journalism that in the past would’ve played well with Jones’ devoted following but flown under the mainstream radar. Now, they’re a national story. Even Jones’ family life, a subject that, pre-Trump, would have seemed unworthy of attention, is front-page news.

Jones is a broad-shouldered, 5-foot-10 bundle of kinetic force. His face can contort from rage to delight to confusion to deep earnestness in mere seconds. A greeting from him feels like shaking hands with a rib eye. On any stage, he is a virtuosic broadcaster and entertainer; the moment he speaks, he is utterly magnetic.

All that energy does not enjoy being contained. But under the fluorescent lights and creaking ceiling fans of the Travis County courthouse, Jones was legally prohibited from doing what he does best: speak his mind. It was unfamiliar territory for him and, if the constant sighs and pained looks were any indication, it was excruciating.

Jones was armed with the best defense money can buy in Austin. (One of his attorneys, David Minton, is such a staple in the local legal community that his father’s name is adorned on the street sign leading to the courthouse parking lot.) His lawyers argued successfully — and unprecedentedly, according to three family law attorneys — to exclude nearly every bit of Infowars and Jones’ professional life from evidence in the trial. All Jones needed to do to keep his children was to show up, maintain his composure, and assume the role of devoted, stable father.

But he couldn’t do it. His frustration with the opposing legal team was theatrical and palpable; when irritated, which was often, he’d narrow his eyes into a piercing squint and, sometimes, point menacingly. Eventually, he was ordered to switch chairs to be out of the attorney’s eyeline. The judge admonished him at least a dozen times. And out of the courtroom, Jones ignored a court gag order, posting YouTube videos about the media’s coverage of the case.

Jones’ trial was never about Infowars. In the end, his defense barely touched the concept of “performance art.” It’s a moot question, anyway: Whether or not Jones truly believes what he says on air, he inhabits the role so thoroughly, and to such effect, that the distinction is academic. In the courthouse, with no cameras to speak of, Jones was the spitting image of the man behind the Infowars microphone — the reactive, impulsive, seething, occasionally charming, and always outrageous character on which he built his empire. Alex Jones, in other words, could not — even at the risk of losing his family — refrain from being Alex Jones. After all these years, he still can’t stop getting punched in the face.

After nearly 10 hours of deliberation, 10 of the 12 jurors in his case ruled against Jones. As the verdict was read, Jones’ face, for the first time in nine days, was blank. ●

Outside Your Bubble is a BuzzFeed News effort to bring you a diversity of thought and opinion from around the internet. If you don’t see your viewpoint represented, contact the curator at bubble@buzzfeed.com. Click here for more on Outside Your Bubble.