DELRAY BEACH, Florida — One early evening last October, a group of young men and women were hanging out at the Starbucks on the main drag here, Atlantic Avenue, smoking cigarettes and bullshitting. They were sitting next to a pile of suitcases, the telltale sign of an addict looking for a place to stay. Some get kicked out of their old halfway house because they relapse; others because their insurance coverage has been used up.

These kids, like hundreds or even thousands of others like them in Delray, are easy targets: They’re often broke and far from home, with limited support from family and friends; they can be mentally and physically unstable; and they’re frequently running from parole or pending court cases.

The people targeting them are variously called “marketers,” “body brokers,” and even “junkie hunters.” They know addicts better than anyone (and many used to be addicts themselves). They spot kids dragging suitcases along the road and ask them if they need a place to go. Their phone numbers circulate in South Florida among the untold addicts looking for “clean time” — or those looking for a flop house that will let them get away with using drugs.

In the midst of a national opiate epidemic, politicians are talking a lot about addiction treatment. In February, Obama asked Congress for $1.1 billion in additional funding to combat opioid and heroin addiction. Hillary Clinton wants to increase addicts’ access to treatment programs. Ted Cruz, whose sister died of an overdose, has mentioned counseling, Alcoholics Anonymous, and “securing the borders” as solutions to the epidemic. But few if any of these public discussions address what “getting help” actually looks like.

In South Florida’s Delray Beach, home to hundreds of rehab facilities and halfway houses, scams abound to profit off of addicts and their insurance policies. The recent uptick in addicts adds energy to the hurricane, but the biggest driving force for the fraud is Obamacare and the 2008 Parity Act, which together give everyone access to private insurance that's legally bound to pay for rehab. “Marketers” act like headhunters, picking up addicts when they’re down, then bringing them to rehab centers and halfway houses for a fee — usually about $500 per head.

“There's a lot of cynicism around because there's these headhunters that hang out at Starbucks and coffeehouses,” said Harold Jonas, an addiction counselor who has run recovery-oriented businesses in South Florida for 25 years and was one of the first sober-home owners in Delray Beach. “They'll pay people to use because they get a $500-per-head fee to get them into detox.”

Because the best way to milk insurance is to cycle addicts through detox, rehab, and outpatient programs, there’s plenty of incentive to keep them relapsing. Five recovering addicts told BuzzFeed News that some marketers give their recruits money for drugs so they test positive on urine tests when checking into treatment.

“He told me, 'You gotta be dirty to go to detox,'” one addict told BuzzFeed News, describing a marketer who gave him cash for drugs.

The FBI partnered with the state in 2014 on a task force investigating fraud in the $1 billion Florida recovery industry, resulting in at least two closures of addiction treatment businesses, as reported by the Palm Beach Post. But local law enforcement in South Florida isn’t eager to take up the cause.

“The patient brokering stuff, most of that is being handled by the federal government,” Jeffrey Goldman, the chief of police of Delray Beach, told BuzzFeed News by phone. When the police do get a call, they hand it off to the feds.

Byron Ira, a 45-year-old from Indiana who’s recovering from drug addiction, shows how easily a brokered patient can become the broker.

After going through rehab in his home state and relapsing, in November 2015 he contacted the HART Foundation, a nonprofit group that connects addicts with rehab centers. He then got a text, he says, from someone in the sales office of a rehab center in South Florida called C.A.R.E. Addiction Recovery, asking for his insurance information and some questions about his drug use.

“The next call I got was flight information,” he told BuzzFeed News. “The day after Thanksgiving, I got picked up at the Fort Lauderdale airport.”

(Mitchell Wallick, the executive director at C.A.R.E., said the facility only pays for patients’ travel if they sign a promissory note promising to pay it back; Ira denies signing anything before his flight, though he notes it’s possible he signed something during his intake once he was in Florida. He says he has never received a bill of any kind from C.A.R.E.)

Ira had googled the place ahead of his flight and was expecting a 12-step-based holistic center far from home where he could change his life. Instead, he spent most days at “the Center,” an office building where addicts did group and individual therapy, but not based on the 12-step program. Nights were spent mostly back at the residence, a two-bedroom apartment housing four men.

The residence and the Center were understaffed and crowded. During his 23-day stay, Ira estimates he made it to only about five 12-step meetings outside the rehab center, because the staff didn’t have access to enough vans to take the residents anywhere. (Wallick denied these allegations, saying that patients are taken to 12-step meetings every night.)

Shortly before Christmas, Ira’s counselor at C.A.R.E. told him he was ready to rejoin life on the outside. But the doctor in charge of the counselors didn’t want to hear it. Ira was told that if he chose to leave, despite his counselor’s recommendation, it would be against medical advice.

Out of the almost $22,000 the program charged Ira’s insurance, they were only reimbursed $1,638.50. So Ira believes that they were trying to keep him another week in order to cover the cost of his flight. Wallick declined to confirm or deny that Ira was a patient, citing privacy laws.

Ira left the facility. A few weeks later, a man who Ira says was a patient at C.A.R.E. during his stay texted Ira with an offer. The former patient said he was making $1,500 for every insured addict he recruited to C.A.R.E. He invited Ira to join in recruiting patients, but Ira says he declined to participate.

“If this is going on, there will be hell to pay,” Wallick said about the brokering accusations. “I would close that damn program down — pardon my French — before I would allow anything illegal or unethical to go down under my license or my name.”

In Florida, the line between illegal patient brokering and legal marketing is simple, according to Jeffrey Lynne, a Delray Beach–based lawyer who routinely represents businesses in the recovery industry. It’s legal to pay someone a flat rate to market your treatment center by setting up an advertorial website, for example, or by recommending your center after doing an intervention.

But under the Florida Patient Brokering Act, paying a marketer a per-head fee for addicted patients, or offering any kind of financial incentive directly to an addict to entice them to pick your service, is a third-degree felony.

Not that the law means much, given the way it’s currently enforced. Law enforcement doesn’t have the resources to track down these marketers, and prosecutors don’t have the motivation to work hard for little payoff. “If you have a victim who’s a co-conspirator with the marketer, how are you going to prove it?” Lynne told BuzzFeed News. “It takes a lot of manpower to prosecute, and for what?”

The victims — the addicts — become implicated in several ways, usually by getting free stuff in exchange for their insurance information.

Halfway houses often set up addicts with in-kind kickbacks — like cell phones, grocery store gift cards, and free rent — if they agree to attend an affiliated outpatient program, a violation of the anti-brokering law. Halfway houses can’t charge insurance companies for anything beyond a simple urine test, so they often partner with outpatient rehab centers that can charge hundreds of dollars a day for treatment services. The halfway house operators take an (illegal) cut of the profit in exchange for feeding patients to the outpatient programs, which covers the addict’s rent — and more.

Sometimes an addict can earn a little extra cash as a “mole,” checking into another detox center or halfway house and recruiting patients away to their employer’s programs.

Steve, who has worked at several treatment centers in South Florida over the years and asked to not use his full name because speaking to the media would affect his employment, has seen this firsthand. While working as a behavioral health technician at a rehab center in Pompano Beach, Florida, a man came in for a short stint, known as a “two-week stabilization.”

Steve noticed that he was very personable, chatting with everyone. A previous experience with a suspected mole had taught Steve to be wary, so one night after curfew he sat the new kid down and pressed him on whether he was being paid to steal patients away.

The kid broke and told him the details of the scam: For every person he convinced to leave, he’d get a few hundred dollars. “I said, ‘Do you realize these guys have pimped you out?’” Steve said. “It’s really easy to get people who are vulnerable and in need of money to say yes.”

Goldman, Delray Beach’s chief of police, confirmed to BuzzFeed News that this is a problem. “Moles are going in and they’re trying to tell Johnny that this place is better,” he said.

But not everybody wants to work for somebody else. It’s easy for someone in early recovery to start eyeing the marketers’ and owners’ fancy cars and wads of cash and decide to make big deals of their own.

“People come in, within six days, they’re counting how much money we’re making,” Jonas, the sober-home operator, told BuzzFeed News. “They get out six months later or less, and they’re opening their own [house] — they’re under 30 years old, they don’t have any real recovery time.”

And the cash rolls in. “You sit on Atlantic, you watch the Lamborghinis and the Bugattis go by,” Jonas said.

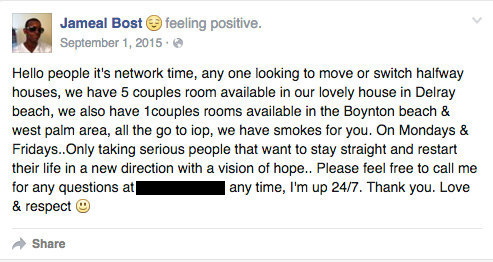

Some marketers will pay the first few Obamacare insurance premiums for addicts they pick up off the street. According to Chris Harshbarger, who has lived in several sober homes in Palm Beach County, one such marketer is Jamal Boyd, the past owner of Ambitious Venture, a halfway house. (The house’s Facebook page claims it’s accredited by the Florida Association of Recovery Residences, which a spokesperson for FARR says is untrue. Boyd told BuzzFeed News he closed the house in February.)

Around August of last year, according to Harshbarger (who is now in jail for an unrelated charge), Boyd offered to pay his insurance premium on a Cigna plan in order to place him in an outpatient program and halfway house that Boyd is affiliated with. He declined Boyd’s offer, he says, and had trouble finding halfway houses that would let him live there without attending outpatient programs that would give the houses insurance kickbacks.

Boyd told BuzzFeed News that Harshbarger’s claims are the result of a personal beef. He said he offered Harshbarger technical assistance in choosing an insurance plan, but did not offer to pay his premiums. Boyd acknowledged that some “other marketers” do pay insurance premiums for addicts seeking treatment, but said that he refers clients who can’t afford insurance to a nonprofit for assistance.

Between 2012 and 2014, while Boyd was living in halfway houses himself, he said, he did take per-head fees from marketers to refer his friends. “They tell the kids, OK, I get X amount of dollars if you can find people who need to go to detox,” he said. “Through their commission, they would kick me back something like 50 or 100 bucks. The most I was getting paid was $250 for a 30-day treatment.”

Boyd opened the Ambitious Venture house in 2014. He told BuzzFeed News that clients who went to an affiliated outpatient program paid a lower weekly rent than those who didn’t. He is a certified medical assistant, and he said those outpatient programs paid him between $150 and $250 a week to conduct “aftercare” visits with their mutual clients.

Boyd had trouble describing exactly what his aftercare services entailed. “I basically just check on them and see how well they’re doing — it’s just a basic assessment,” he told BuzzFeed News.

The kickbacks Harshbarger describes are a symptom of a much larger issue, one that is taking its toll on the Florida rehab industry’s reputation. For instance, the mega-insurer Cigna, citing rampant health care fraud, pulled out of the Florida health care exchanges for 2016.

One woman, who requested to remain anonymous for fear of repercussions within the community, told BuzzFeed News about getting $250 a week to do an intensive outpatient program (IOP) in Delray. When her boyfriend, a marketer for the business, failed to bring enough new clients in, the owner cut them off. The woman contacted another marketer, who brought her to a new house.

“They pretty much knew I was only there to get a cut,” the woman told BuzzFeed News. But during her intake at the second house, she says, a doctor inappropriately touched her breasts and pulled down her underwear. A victim of previous sexual assaults, she panicked and demanded to leave.

“After that I told all the body brokers to stay the fuck away from me,” she said. “Even at this point if I relapsed, I would never go back into a halfway or into an IOP.”

This layer of cash-only illegal activity creates cracks in the system, where lawbreakers (some with active drug problems) become the rich and powerful gatekeepers to treatment, housing, and even cash.

“We’ve heard it all — we’ve even heard that these [halfway] houses, some of the bad operators are selling drugs in them,” Jeffrey Goldman, the chief of police of Delray Beach, told BuzzFeed News in October.

Marketers pull addicts off the street, said Jessica Bostic, a 26-year-old from Ohio who came to Delray last year for rehab. “There’s a kickback if you’re the person who signs them into detox for referral. I was offered to go into a [rehab center] for two weeks for $1,000 — they would give you a portion of the referral fee.” But the marketers told her she would have to “do something” to qualify for detox — that is, use drugs.

With addicts in such a vulnerable state, being offered money, drugs, or both, these marketers sometimes use their power to make sexual demands as well.

Bostic relapsed on and off for her first month in Florida. One day she overdosed on the beach where she’d slept the night before. A friend revived her, took her to the hospital, and called Jameal Bost, a well-known marketer around Delray Beach. Bost knew Bostic was “running” — still using — and looking for a safe place to stay.

He set up Bostic and her friend in Redemption House, a halfway house where Bost was a house manager. She overdosed again in the bathroom that night, and Bost helped revive her.

After Bostic left Redemption, Bost sent her dozens of Facebook messages between July and September 2015, ranging from offers of cash to assistance in finding another halfway house. Once Bostic told the marketer she was not interested, he responded defensively:

“look girlfriend you’re not my type nor on my level I have 15 months clean what would I [do] with u? What can you do for me I don’t want you!!”

“Lol ok,” Bostic responded. “Later.”

The next day Bost messaged her again, repeatedly asking her out and then getting angry when she told him to leave her alone. “Pisssssh you ain’t no body [in] town but another junkie that don’t want shit in life,” he responded. “U ow[e] me a big apologie but that’s too good for u.”

Bostic says a big part of the problem is how easy it is for addicts with very little clean time to suddenly start making big money selling people they know to rehab centers.

“Everybody needs to make money,” she told BuzzFeed News. “But when you’re in it for the money and you could give a shit less about the person, it’s very dishonest.”

Bostic’s story is not unique, according to Susan Ramsey, a West Palm Beach lawyer who often represents people in the recovery community in South Florida.

She knows of dozens of legal cases of sexual assault or misconduct throughout the recovery industry in South Florida, many involving techs or counselors having sex with residents.

“They don’t all bring cases —in fact most of them don’t,” Ramsey told BuzzFeed News. “Frankly, there’s a double stigma — because people don’t think drug addicts can be sexually assaulted, plus any time a woman says this, unless there’s video, it’s a problem.”

One of Ramsey’s clients, an alcoholic with a pending DUI case, was allegedly encouraged to drink by a technician at her halfway house, and then sexually assaulted by him. When she reported it, she was interrogated by the staff and forced to sign a written retraction. She left, and spent the night in a parking lot. The facility did not contact the police.

Some members of the recovery industry even become pimps, like Kenny Chatman. The Palm Beach Post reported in December 2015 that Chatman, who ran several halfway houses in Palm Beach County, was actively pimping women out, getting them high and listing them on a local prostitution site. According the the police report, at least one woman was kept there against her will.

Florida has struggled to regulate the recovery industry. The last legislative session saw several laws passed, including one that says rehab centers can only refer clients to halfway houses certified by the Florida Association of Recovery Residences to meet a certain standard. There are many people in South Florida who are honestly trying to help addicts recover, and follow strict codes of ethics around how to behave.

But legal experts say relying on goodwill isn’t enough. The Florida Department of Children and Families (DCF), the body tasked with regulating rehab and detox centers, is woefully underfunded, they say, and doesn’t have staff to enforce its own regulations. And it doesn’t have any power over halfway houses.

Lynne, the Delray Beach lawyer, hates when his clients ask him what the risk is if they engage in illegal marketing. “I can only tell you what I know to be true — there is no DCF police out there, there’s no DCF money out there, and the police aren’t prosecuting,” he told BuzzFeed News. “It does violate the law. But they come to me and say, ‘Jeff, if I don’t do it, I can’t even be in the game.’”

DCF says it reports all alleged patient brokering to the attorney general, but otherwise has no power to do anything about it.

“DCF does not deny patient brokering exists,” Michelle Glady, the agency’s press secretary, told BuzzFeed News by email. “DCF does not have legal authority to investigate patient brokering and can only legally revoke a license if minimum standards are not met.”

Ultimately, the worst problems may come from the fact that so many addicts are searching for recovery in a place where drugs — and their consequences — are easy to find and hard to avoid.

“People die every week,” Bostic, the 26-year-old from Ohio, said.

And they’re not just dying in Delray Beach. Nationwide, 125 people die of drug overdoses every day. Politicians pay lip service to “evidence-based treatment.” But the truth is, nobody knows the best way to get an addict off drugs.

There are few numbers on how many addicts get clean in rehab, and even fewer on how many stay clean. By nature, it’s a transient population, difficult to track for the multiple years required to get solid evidence of efficacy. And there’s little incentive for rehab centers to shine a light on relapse rates, which likely hover around 90%.

Carrie Schoewe, a 41-year-old originally from Ohio who got sober in South Florida, told BuzzFeed News she thinks that short stays in sober homes can be beneficial, but that many get trapped in the cycle of relapsing with other addicts in early recovery.

“I think for a small period of time, people who understand where you are and what you’ve been through can be really supportive,” she said. “But it’s not staying stuck in a place, it’s what you do after. And there don’t seem to be afters for a lot of people.”