A dozen or more people are crammed into a second-floor office at Impact Hub, a thrumming co-working space in Oakland's rapidly developing downtown -- philanthropists, lawyers, venture capitalists and labor organizers all clothed in some variation of "business casual." On one wall, a floor-to-ceiling sheet of plexiglass reveals the scene on the ground floor, where dozens of founders and would-be founders are making phone calls and sending emails. On another, a single hanging bookshelf displays, among other tomes, a copy of Thomas Piketty's Capital, the nuevo-Marxist best-seller that invigorated the national discussion about inequality when it was published in 2013.

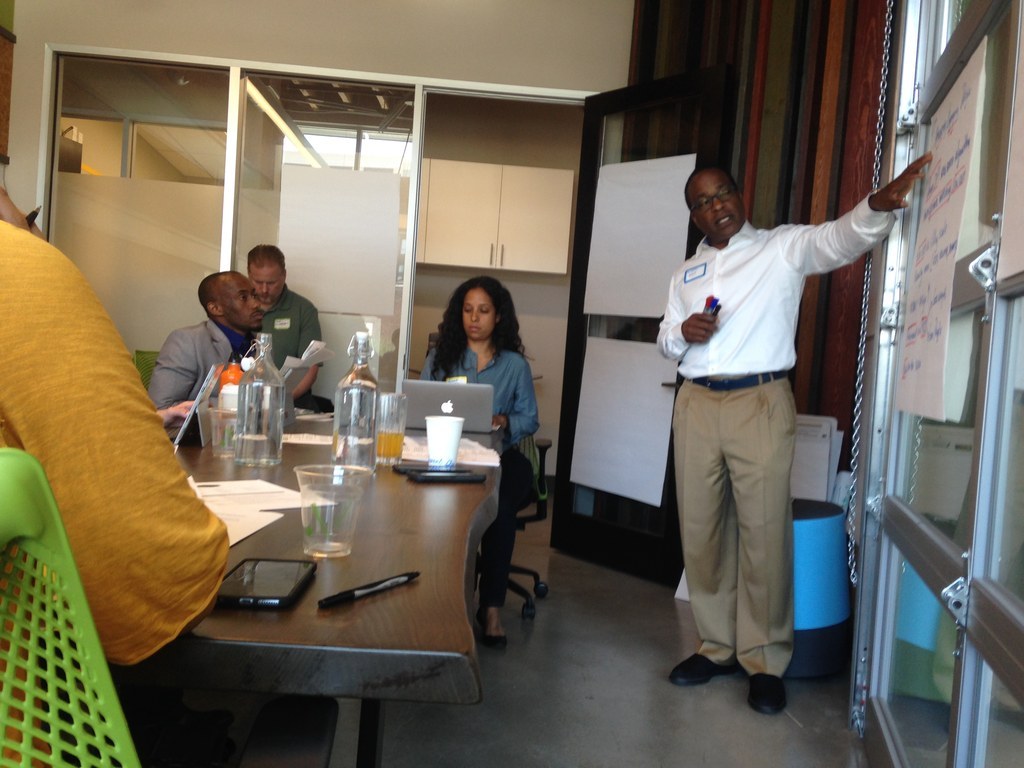

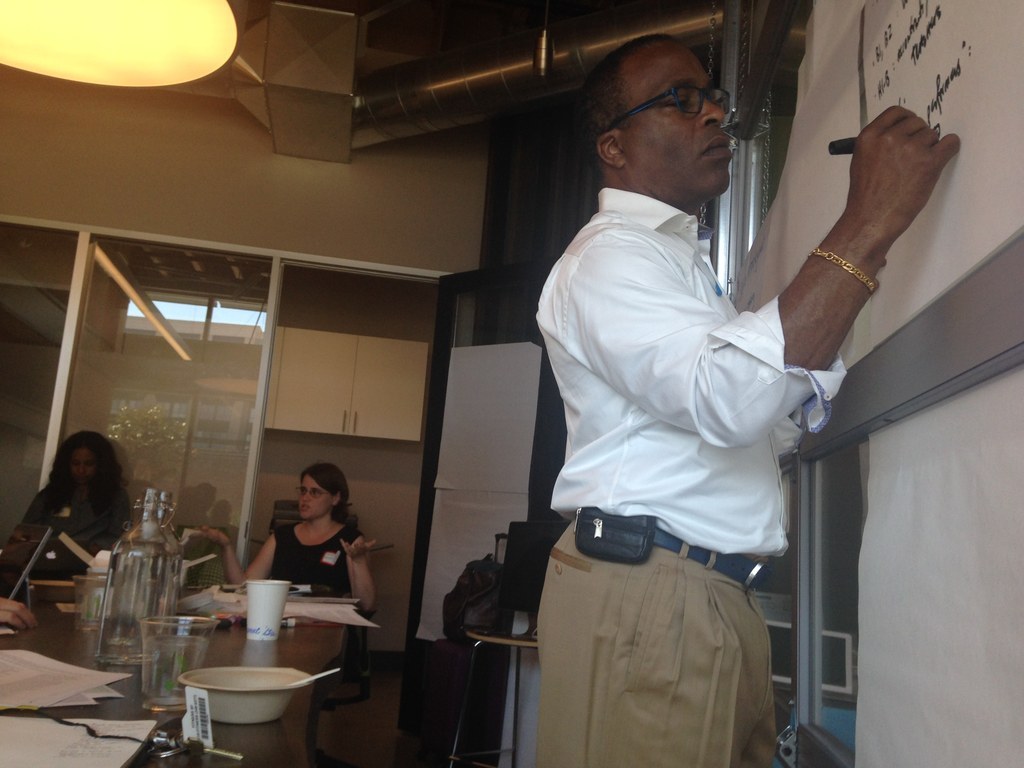

It's the last day of The Workers Lab summer institute, a two-day workshop for aspiring entrepreneurs looking to turn their big ideas for empowering workers into sustainable businesses. Though Workers Lab CEO Carmen Rojas and president David Rolf are both present, the man of the hour is clearly Stanford Business School lecturer Michael Bush. Bush has been called in as a consultant to walk the five participating projects through his nine building blocks of revenue-generation. He wears a gold watch on one wrist and a gold bracelet on the other.

Knocking business sense into do-gooders is something of a hobby for Bush, whose day job involves consulting for large corporations. "That's my capitalism," he told me. But for decades, he's also done pro bono work in the Oakland community, helping nonprofit directors and the like come to realize that making money is the only way to make real change. Bush teaches a business class at the Impact Hub — where the Wi-Fi password references SayHerName, a campaign against police killings of black women — every Monday night. He says he always starts the class with the same announcement: "I'm going to talk about money."

The Workers Lab receives funding from the Ford Foundation and the Open Society Foundation, but at heart, it's a project of the Service Employees International Union. David Rolf is president of both the lab and the SEIU's Local 775 in Seattle, the project's major financial backer. Rolf has been public about his lack of faith in traditional organized labor's ability to defend the American workforce going forward into the 21st century. He says he's committed to finding a better solution.

A big part of that commitment is The Workers Lab, an experimental, five-person organization studying whether the principles of capitalism and the structures of startup culture might produce better outcomes for workers today. The two-day institute was an exercise in taking nascent ideas for recruiting networks and organizing platforms and seeing if there might be a way to turn them into financially sustainable projects insulated from the fickle whims of philanthropy.

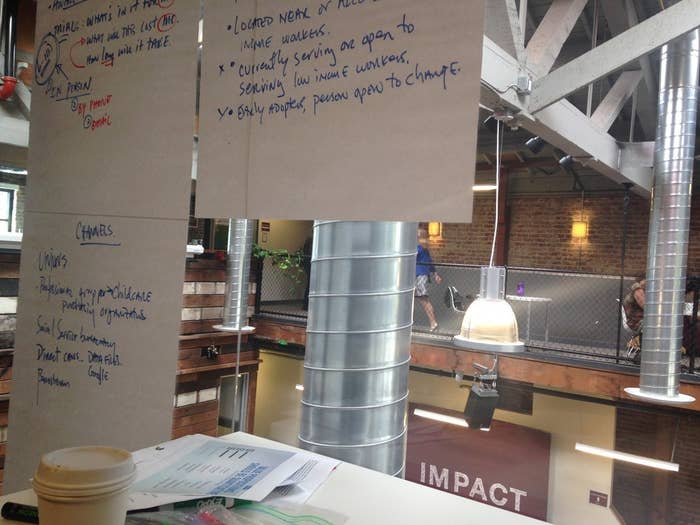

Bush's process, which involves many poster-size sticky notes on the walls, embodies the agile, aggressive, early-stage startup business strategy that Silicon Valley has become known for. Teams must identify their customers, their immediate and long-term goals and their available resources. They must also draw up operating budgets, determine their value proposition for customers and potential partners and, crucially, target their most promising revenue streams. The point of the process: determine the most logical business plan on which to build their fledgling start-up and identify the steps that need to be taken to execute it.

"Are you going to be for-profit?" Bush asks Chelsea Sprayregen, one-third of the founding team of a child care project that came in named "Work Hard, Play Hard" and left as "Provide." After a second's hesitation, she replies in the affirmative.

"Good," Bush said. "I like that."

With Provide Sprayregen wants to make life easier for working parents and child-care providers by taking better advantage of government child care subsidies. Parents working irregular schedules often have difficulty accessing affordable child care; by helping them pool together already available but underused resources, Provide hopes to make child-care easier for parents and more profitable for child-care providers, many of whom are low-income women with families of their own.

If Sprayregen and her co-founders were seeking funding from philanthropic organizations, they might present Provide as an effort that will positively impact the lives of working parents and child-care providers both. But Bush coaches them to instead tout how their product can help potential buyers and partners save money --which is why he prefers the idea of them incorporating as an LLC.

For example, Rolf explains, unions have a lot of money and are often searching for new perks and benefits that will help them shore up dwindling membership. If Provide were able to convince a union that subsidized child care is something a majority of it members want, that union could become a lucrative business partner. Bush writes "unions" on one of the giant Post-its, and just like that, traditional labor becomes a potential customer for the new labor movement.

Not all of the projects workshopped at Workers Lab are new. Working World, for example, a lending institution that provides funding to worker-owned businesses and cooperatives, has been around for over half a decade. Labor Exchange, a platform where low-income people of color can search for jobs, is the brain child of Yscaira Jimenez, who took the idea through MIT's Sloan School of Management and came out with some preliminary funding, contacts at companies like Yelp, Google and Facebook, and a new co-founder, Sheldon Trotman. Bush tells Jimenez it's clear that she had read his nine building blocks to revenue before the event. He looks very happy when he says this.

Another participant that came into the institute with something to show for itself already was OUR Walmart, a group representing the collective efforts of 5,000 active members, plus a 56,000-person strong Facebook page. OUR Walmart, a now independent group that once operated in tandem with the United Food and Commercial Workers union, recently celebrated a major victory when Walmart agreed to raise workers' wages. Dan Schlademan and Andrea Dehlendorf, who together are working to rebrand OUR Walmart as a more agile and tech-forward organization, came to The Workers Lab looking to capitalize on the momentum they've stirred up among employees of the big-box retailer.

The two of them have already managed to raise around $1 million in small donations from workers, which made their project the easy favorite of the institute. What they want to do next is build a stand-alone app that could become a platform for collecting membership fees or soliciting donations as well as for organizing actions and protests in a more efficient and controlled way than what the Facebook group currently allows.

To encourage members to engage with a new app, the OUR Walmart team is considering offering a number of incentives, including child care, financial services, and legal information. Revenue could potentially come anywhere from advertising to membership dues to data mining — low-income to middle-class workers are, as Schlademan and Dehlendorf are well aware, a demographic that plenty of outside groups with deep pockets, especially in politics, are looking to learn more about. If capitalizing on that fact helps to monetize an app that could ultimately power instant, flexible, on-the-ground actions for workers, it could be worth it.

OUR Walmart's pivot is the result of what Dehlendorf called "a change in leadership." The union decided it would be more productive to fund media campaigns that focused on traditional tactics like TV ads than an app or a digital platform, and Dehlendorf and Schlademan, as BuzzFeed News reported in July, found themselves out of a job.

A similar situation brought Rachel Micah-Jones to The Workers Lab. Micah-Jones is assistant director of Centro de los Derechos del Migrante (CDM), where she runs a project called Contratados, a digital platform that allows migrant laborers in the U.S. to rate their employers, providing warnings to would-be workers about potential scams and abusive workplaces. For a long time, the project had a funder that was interested in worker protections and immigration — until, suddenly, it didn't. Despite offering an important service to hundreds of workers a day, Contratados found itself in need of a sustainable, reliable source of funding. But as it turned out, it's not easy to find ways to make money off a vulnerable population without there being some kind of collateral damage; there's a reason, in other words, that good business and do-gooding don't often go hand in hand.

"We've had offers to buy certain information and we've chosen to not accept them, because we weren't sure they were the right partners, whether or not they advance our mission," Micah-Jones tells the group at The Workers Lab. She's rejected offers from private companies hoping to use Contratados as a cheap way to check up on suppliers with potentially exploitative labor practices.

Given that history, the group gathered at The Workers Lab decides that if Contratados is serious about achieving independence from funders, there is only one option left: charging users. Micah-Jones is uncomfortable with the idea, citing the organization's commitment to transparency.

"How does taking money from someone make it less transparent?" asks Anthony Heckman, a lawyer and former Lehman Brothers analyst.

"They don't have the same access," Micah-Jones replies. "There's something in my stomach that I can't..." she trailed off. "In my throat…"

An uncomfortable silence falls over the room. On the one hand, the idea of charging already-exploited workers for access to information that could protect them from further abuse sounds ridiculous. On the other hand, without recurring revenue, Contratados's future could be left in the hands of capricious lending institutions. Micah-Jones seems at a loss.

"We on the left have a romance with powerlessness," says Rolf, in an attempt to raise her spirits. "We stay small and dependent on foundations of our major donors or voluntary contributions and all the things that trap us in a cycle of dependency and ultimately kill our mission."

Rojas puts it even more bluntly, saying, "Philanthropists talk about cooperation and programs until they don't want to give you money."

Ultimately, Micah-Jones leaves Workers Lab invigorated, but unsure how to move forward. Most of the ideas for revenue generation — or, as she terms them, "money schemes" — appear to leave a bad taste in her mouth. The next day, when I ask Bush what he thinks will happen with the project, he tells me that he's not in the business of changing minds.

"Some people," he says, "are just allergic to capital."

There are over two dozen people on the advisory board of The Workers Lab. Among them are labor organizers, philanthropists, business owners, advocates, lawyers, bankers, and more. Some of them, Rojas tells me, see the lab as a new alliance working toward the same goals the labor movement has always had — higher wages and better benefits, especially for low- and middle-wage workers. But others, she says, see a bigger opportunity in collaborative digital platforms and innovative funding structures; they believe the worker advocacy movement is at a real crossroads, and this is a chance to upend the status quo.

"We need to teach people that empowerment and power are actually different," Rolf explains. Empowering workers, Rojas says later, means giving them a voice, or advocating for improved conditions. Power, on the other hand, means collective action or access to capital. If that means adopting the tactics of the opposition — from dark money funds to data mining — so be it.

Not everyone in the group thinks Micah-Jones is wrong to resist monetizing Contratados' user base. Some stay silent on the matter. Aaron Tanaka, a venture capitalist with the Boston Impact Initiative, actually spoke up in her defense. Tanaka, I later learn, ran a nonprofit called the Center for Economic Democracy in Boston before turning to funding what he called "long-term alternatives to capitalism." The center, which is still around, housed a number of social impact projects that were also meant to be financially sustainable. But, Tanaka says, it was harder than he thought to raise funds and pursue revenue without compromising some of the core goals.

Making money is hard, and making money without any collateral damage to pro labor principles and workers themselves is even harder. It's one thing to adopt the language and aggressive stance of startup culture; it's entirely another to execute on it successfully. The Workers Lab wants to train labor organizers in the language of Silicon Valley, and outfit them with the dark arts of business school, in hopes of reinvigorating what is widely seen as a dying labor movement. But lots of startups have tried and failed to prove that social good and profit can be perfectly aligned.

"I don't know if the goal of self-sustainability is worth the sacrifice," said Tanaka. "In society, certain things ought not be profitable."