Nextdoor, a location-based social network for neighbors that has more than 10 million registered users, is rolling out a new tool today that the company says has reduced incidents of racial profiling on its network by 75% during tests. In recent years, so many people have used Nextdoor to report things like black men driving cars or hispanic women knocking on doors as suspicious or even criminal that the site has become known as a hub for racial profiling.

The new tool, an algorithmic form for reporting crime and safety issues, has been in beta for an ever-increasing portion of Nextdoor’s 108,000 neighborhood groups since May. This feature, which automatically identifies racially coded terms and prevents users from posting without supplemental descriptors, goes live for all users today.

“The impact of being racially profiled in general is terrible,” CEO Nirav Tolia told BuzzFeed News on Tuesday. “It runs counter to the mission of Nextdoor. It’s something we feel morally obligated to take seriously.”

Racial profiling became an issue for Nextdoor in 2015, when a number of news outlets reported on the frequency of posts about crime or suspicious behavior that mentioned an individual’s race, but little or nothing related to actual criminal activity. In many cases, these posts would refer to people of color doing things such as talking on the phone or walking a dog.

Tolia said it wasn’t the bad press, but the work of civic groups in Oakland that brought the issue to his attention. Nextdoor touts its collaborations with police departments, city governments, and other public agencies. Last fall, Oakland Vice Mayor Annie Campbell Washington encouraged Oakland city departments to stop using the app to communicate with citizens until Nextdoor addressed the issue of racial profiling. By October, Tolia’s team was holding working groups with advocacy groups and city officials, and together they came up with a solution.

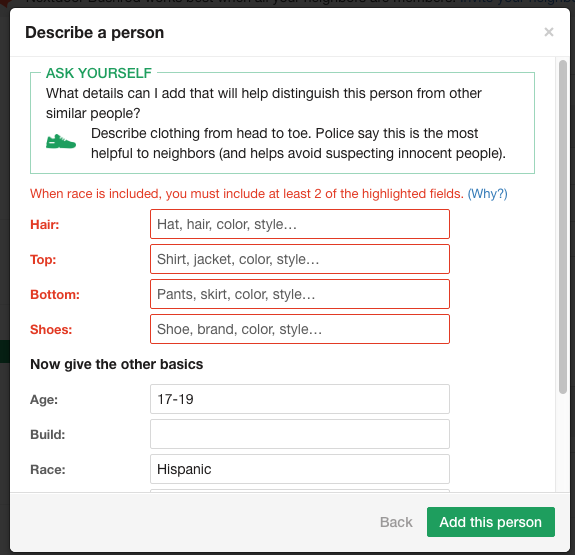

The idea, which Tolia credits to members of a group called Neighbors for Racial Justice, was to change the way crime and safety issues are reported on Nextdoor. Instead of a blank text box and subject line, it was suggested that Nextdoor design a form that more closely resembles a police report or 911 dispatcher questionnaire. By explicitly requesting details about height, clothing, and age, they would discourage people filing reports from focusing exclusively on the race or ethnicity of the subject.

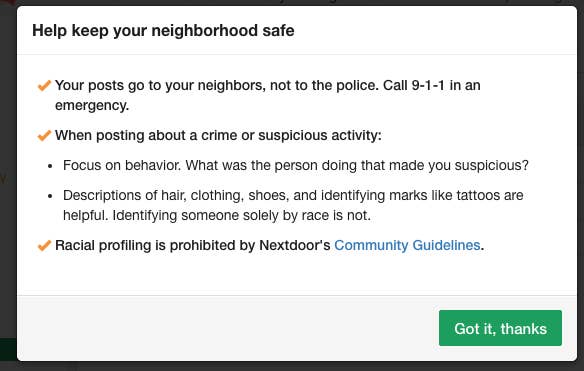

Nextdoor features a wide variety of post categories — Classifieds, Events, etc. — but it’s the Crime and Safety section where people tend to focus on race to the exclusion of other salient details. As of today, Nextdoor neighbors posting a “crime” or “suspicious behavior” to the site will be warned against allowing an individual’s race to color their interpretation of events. And if their post focuses too much on the race or ethnicity of the subject, they’ll be prevented from publishing it. “When race is invoked, we create a higher bar,” Tolia explained.

For example, try to post about your car windows being smashed, and you’ll be prompted with this message:

Try to describe someone with just a racial characteristic, and you’ll see this prompt, asking you to be more descriptive:

Nextdoor claims this new multi-step system has, so far, reduced instances of racial profiling by 75%. It’s also decreased considerably the number of notes about crime and safety. During testing, the number of crime and safety issue reports abandoned before being published rose by 50%. "It's a fairly significant dropoff," said Tolia, "but we believe that, for Nextdoor, quality is more important than quantity."

Vice Mayor Washington said she’s “thrilled” with the results Nextdoor has achieved. “I don’t think a lot of technology companies would have taken the steps they did, and made significant changes to their platform,” she said.

When tech companies come under fire for failing to take race issues seriously — Snapchat, Twitter, and Airbnb are examples — critics often assert that, were minorities better represented on the staffs of those companies, the same mistakes might not have been made. But Tolia, who himself identifies as a person of color, said that while he's working actively to diversify Nextdoor's staff, when it comes to racial profiling, "we believe we get the best information from our members, and in this case, our advisers.”

But not all of Nextdoor’s advisers on the racial profiling project are satisfied with how the process turned out. Two founding members of Neighbors for Racial Justice, Audrey Williams and Shikira Porter, said Nextdoor left them out of the development process after a flurry of early interest. Porter told BuzzFeed News that she continues to see instances of racial profiling in her Nextdoor neighborhood despite the rollout of the form. Nextdoor confirmed that the company has not met with Neighbors for Racial Justice since the test pilot began in April, but said it was made aware of only two instances of racial profiling that had slipped through its algorithms in the last few months.

“We've been doing the work of consultants for them, and they’ve been taking it as free, pro-bono, volunteer advice from the community,”said Williams, who works in digital marketing. “And we’ve been happy to give it, because it makes our lives better. But over time, it began to feel a bit like exploitation.”

Nextdoor will hold a conference call for local stakeholders on Wednesday, but neither Williams nor Porter will be able to attend. Porter said it “didn’t feel right” to have Neighbors for Racial Justice attached to a project they felt the organization hadn’t been given a chance to sign off on.

"We appreciate working with [Neighbors for Racial Justice] to create these improvements,” said Tolia in a follow-up email. “We are encouraged by the progress, but know there is still more work to do."

However, it’s clear that the contributions of Neighbors for Racial Justice and other local organizations to Nextdoor’s efforts were integral to the design and execution of the final product. Some of the copy Nextdoor ended up using in the form — such as, “Ask yourself, 'Is what I saw actually suspicious, if I take race or ethnicity out of the question?'” — came at the suggestion of Neighbors for Racial Justice.

The new racial profiling form isn’t the only change Nextdoor has made in service of tempering racial profiling on its platform. Last November, the company introduced a checkbox that allows users to flag posts for racial profiling. More recently, it's trained the group of in-house customer service representatives that reviews such posts in conflict resolution and “cultural humility” with an eye towards helping users understand why their posts were flagged, and how racial profiling negatively impacts whole communities.

It’s unusual for a tech company to take such an active role in policing its users, or to make an investment in educating them about social and cultural issues. In addition to relying on community members, Nextdoor also hired consultants to help, among other things, define what racial profiling outside of a police setting even is. Debo Adegbile, a civil rights attorney with the NAACP who was nominated for US assistant attorney general by President Obama, and Grande Lum, a race relations expert with the Department of Justice, both worked as advisers to Nextdoor.

Because the new form makes it less likely that users will post to Nextdoor, Tolia said there's a "business cost to doing this." But given the way Airbnb, Twitter, and other tech companies have struggled with issues of race in recent months, it’s easy to see Tolia’s decision to meet the racial profiling problem head-on not just as morality, but also as good business sense.

“Let’s not be fooled,” said Audrey Williams of Neighbors for Racial Justice. “It’s a win for us, and it’s a win for them.”