Scrolling through TikTok's For You page one night, Lily was shown videos of people eating ice chips, sleeping all day to avoid eating, and fasting for days.

The San Francisco-based teen had previously lived with an eating disorder, and she found this content triggering.

She took to the r/EDAnonymous subreddit to share her frustrations. "Has anyone else noticed how proana TikTok is becoming?" she wrote, referring to the eating disorder videos (proana = pro anorexia) that she had been shown.

Some people chimed in with their own experiences of seeing proana content, while others spoke positively about seeing eating disorder recovery videos. Almost all of them agreed on one thing: content about eating disorders is all over TikTok.

The app's community guidelines ban videos that "promote eating habits that are likely to cause health issues", specifying pro-anorexia content or that which encourages dangerous weight loss behaviours. Yet videos that show people uncritically displaying or joking about these behaviours are rife.

Users and experts say the platform's visual nature and algorithm have created an environment that can be particularly harmful, particularly for those who have eating disorders.

TikTok's For You page is a limitless feed of videos recommended by an opaque algorithm based on the user's interactions. What separates For You from Instagram or Twitter's main feeds is that the algorithm will serve videos from anyone on the platform, and not just accounts followed by the user.

This means people can be surprised with videos about eating disorders even if they are deliberately not following anyone who regularly posts about such disorders, or about weight loss or diets.

Anecdotal evidence from users says TikTok's For You Page increasingly shows content about eating disorders after they watch just one video on the topic.

This was Lily's experience. She also noticed a feedback loop between the videos of people trying to lose weight and her own eating disorder: the more she saw, the more she was served, the more she watched.

"The nature of any [eating disorder] is just very competitive," Lily said to BuzzFeed News in a message. "You always want to be the skinniest, you always want to lose even more weight, you're always comparing yourself."

By searching basic terms about weight loss or calories, BuzzFeed News was able to easily find accounts promoting dangerous diets and weight loss goals to their followers.

One such account that claims to be run by a 13-year-old has a dozen videos, some of them viewed tens of thousands of times. In the comments, some users — who also appear to be young — ask about her methods. Others warn that what she's doing is dangerous and say that it's triggering them.

TikTokers also say that outside of explicitly pro-eating disorder content, there's a lot of content that implicitly encourages risky and potentially harmful behaviours.

Emy, 17, said she's constantly coming across borderline videos and comments.

"I've seen some videos, especially from the guy community on TikTok, saying things about how they'd never get with a girl unless she was under a certain weight or how some girls, and I quote 'need to put down the big mac and eat a fu_king salad'," Emy told BuzzFeed News in a message.

Although Emy is an avid TikTok user who's made videos about her experiences with an eating disorder, she said these attitudes make her enjoy the app less.

"I try to scroll past it but when you see it so often it kind of sticks. I try not to let it get to me too much, but it does hit me especially seeing comments on plus sized females posts where they body shame her," she wrote.

Beyond individual accounts, there are multiple popular TikTok sounds — a function that allows audio from an original video to be easily re-used to accompany new videos — about disordered eating.

In one sound, a voice asks "how much more weight are you going to lose?" and another replies "I won't be happy until I reach zero". More than 460 videos on the platform use this sound, and most of them are about eating disorders.

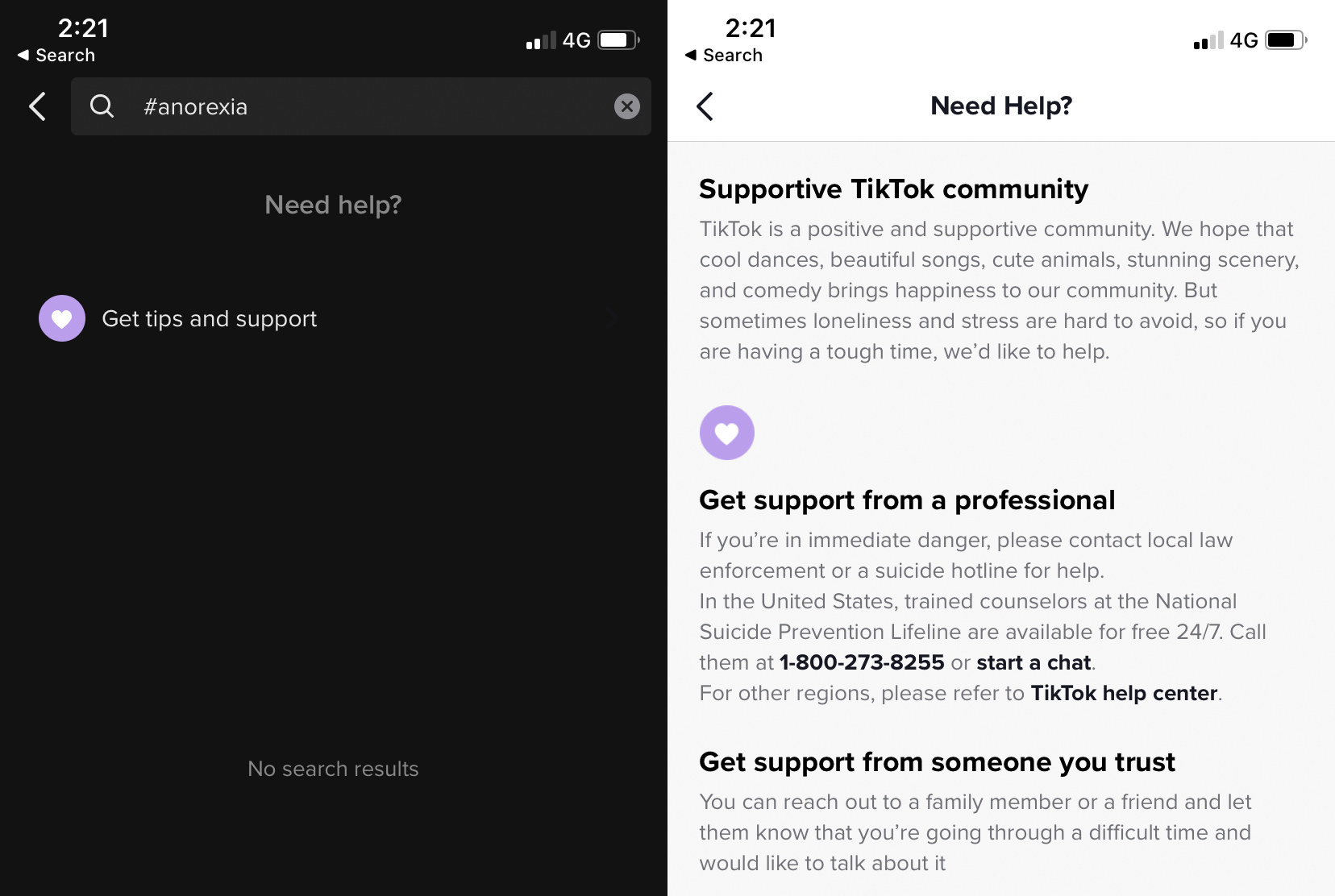

TikTok's owner ByteDance has taken some steps to stop harmful eating disorder content. TikTokers who use well-known pro-anorexia search terms — including #proana or #anorexia — are instead directed to a support page titled "Need Help?". But common misspellings of these terms still return examples of harmful eating disorder videos.

A TikTok spokesperson didn't answer questions from BuzzFeed News about how the company polices videos on the platform, but reaffirmed its commitment to getting rid of them.

The app's "Need Help?" page provides contacts for the United States National Suicide Prevention Lifeline as well as general tips for finding support.

Melissa Wilton, who is the head of communications and engagement at Australian eating disorder advocacy group The Butterfly Foundation, acknowledged ByteDance's efforts to keep their users safe but said TikTok lags behind other platforms when it comes to eating disorders.

She pointed out that it is difficult for many TikTok users across the globe to access information that is relevant to their local support services and resources.

"The ByteDance head office is located in China with no offices in Australia to date. This makes getting a response or forming a relationship challenging," Wilton told BuzzFeed News. "Butterfly has a really good relationship with many global social media platforms such as Instagram and Twitter due to their local presence."

Users and experts have concerns that even videos about recovering from an eating disorder can be harmful, while acknowledging that their impacts are more complex. Some people find this content helps them, others find it triggering.

TIkTok's guidelines allow videos that provide "support, resources or coping mechanisms" for people with eating disorders. "EaTiNg DiSoRdEr ChEcK" and other sounds are filled with videos of people showing before and after pictures of their recovery, or documenting their daily life as they get better.

Some users say the videos are helpful. 21-year-old Chris Henrie uses TikTok to educate people about eating disorders. His videos — which often feature his experiences going through treatment for anorexia nervosa — have been liked more than 1.5 million times.

He said suffering from an eating disorder can cloud your judgement about what is and isn't appropriate to post.

"You tend to forget that your posts are reaching real, impressionable people, and posting triggering content is dangerous for both the creator and audience," Henrie said in a message. "In comparison, any post with a theme of recovery can inspire and educate the public on eating disorders in a fun, creative way."

Maddie Quinn is a 26-year-old TikTok user from the United States. She was motivated to make a video about her own recovery — which has been viewed nearly three million times — to counteract some of the potentially harmful videos she'd seen.

"I kept seeing all of these videos about weight loss, often right after videos of thin, beautiful people with millions of views and likes," Quinn said in a message. "So I wanted to challenge those standards and provide some support to people who might be struggling with EDs."

Quinn is worried about what she calls "pseudo-recovery" TikToks: videos that use recovery language but actually depict people engaging in harmful behaviours.

"I completely understand that making videos or other content is a way to cope, but I’ve noticed that a lot of these recovery videos give specific weights/numbers and show 'body checks' (thigh gaps, collar bones, etc.), which can be extremely triggering to people struggling with EDs," Quinn wrote.

New Zealand's Massey University researcher Dr Andrea LaMarre agreed that recovery TikTok videos can help, but that they don't usually represent the breadth of eating disorder recovery experiences.

"People can connect to other people, and it can allow them to see what recovery might look like," LaMarre said. "But in general, we only see the very polished version of what something is like. They can be exclusionary of what eating disorder recovery might look like."

Dr Gemma Sharp is a researcher at Australia's Monash University and a clinical psychologist. She said eating disorder recovery videos can be a double-edged sword as people with such disorders will seek out these videos to trigger themselves.

"I know from talking to some of my own patients that if they look at a site like this, they would see the before images and go 'I want to look like that'," " Sharp said. "It may even set them back. They wouldn't engage with the rest of the video."

Lily is still hopeful that ByteDance will crackdown on eating disorder videos — but said it won't make a difference to her.

"It wouldn't affect me much, I deleted TikTok," she said.