At 11:21 p.m. Monday night, officials in Ventura County sent a buzzing emergency alert to hundreds of thousands of residents warning of a fast-moving wildfire that had already torn through about 2,500 acres and was gaining speed.

However, about a dozen people say they never received the message and credited their safe escape to police officers screaming into loudspeakers outside their windows, to neighbors who sounded the alarm, or to seeing the fire roar across the dark hills above their houses.

"A police siren blared outside and we had 45 minutes," recalled Pat Erickson from the front steps of her rubble-reduced home. "I grabbed my purse, phone book, and flute, woke up Paul and we just got out."

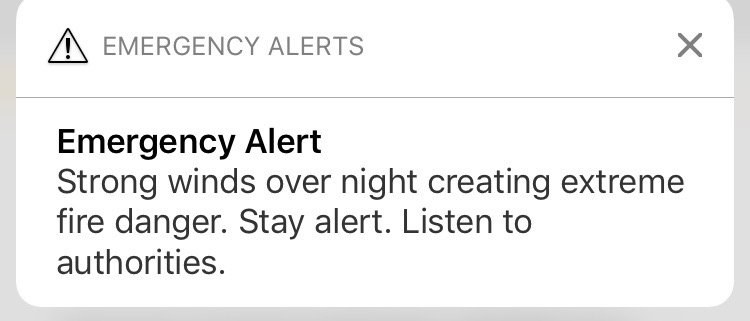

As another set of unruly, wind-fueled wildfires whipped across California, forcing thousands from their homes and torching miles of land at a record pace, state officials made the rare, unprecedented decision to send a blaring, phone-shaking alarm Wednesday night to an estimated 12 million people from Santa Barbara to San Diego counties warning of strong winds and "extreme fire danger."

The alert was the widest deployment of the system to date by state officials.

The Wireless Emergency Alert system, launched by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in 2012, seizes mobile phones with a shake and a siren. Smartphone holders are automatically opted in to receive these messages, which are designed to arrive regardless of one's cell phone service.

In California, the alerts are typically issued by county and city officials, to warn residents of danger or emergencies specific to their area. However, with five barely contained fires swallowing homes and buildings, and displacing thousands at alarming rates, state emergency officials "felt the need to take over and overlay all jurisdictions," Kelly Huston, a deputy director with California Governor's Office of Emergency Services, said late Wednesday, after the emergency message buzzed phones across Southern California.

"The danger is great enough and wide-ranging enough that it warrants us sending this rare kind of an alert," Huston said. "These fires are beyond 'high danger' — they are extreme. Basically, if you are in Southern California, regardless of where you live, you are getting it."

The dangers began in Ventura County Monday evening, when sharp, powerful winds skirted across rural, coastal, and urban communities surrounded by dead, dry fall foliage and brush — conditions similar to those experienced when fires erupted in Northern California this October, consuming entire neighborhoods in a matter of hours, killing 44 people, and decimating nearly 9,000 homes, hospitals, and businesses.

"What happened in Sonoma was an overnight firestorm that happened in a matter of hours. That same potential faced us tonight," Huston said Wednesday. "It was the same conditions. We can't over-alert people in these situations and we felt the need to amplify the severity of the situation using all the tools we can to make them pay attention."

Alarmed by the fire's speed Monday, the Ventura County Sheriff's Department decided to use the Wireless Emergency Alert system to send a vibrating warning to all cell phones in a targeted area. Unlike officials in Sonoma, they blasted the alert out to a huge portion of the county, about 850,000 people, to jumpstart the evacuation process and notify people they should be ready to flee at a moment's notice.

"The fire was like a freight train barreling down toward their homes at an insane pace," Steve Kaufmann, a captain with the Ventura County Fire Department, explained. "We literally needed to get people out of their homes as soon as possible."

Officials at the state level had the same mindset, demanding literally everyone's attention in a red-flag warning Wednesday night, Huston explained.

"This alert is a particularly important tool we use because it gets to people who might not get alerts otherwise or didn't sign up for local alerts," he said. "If people are reachable on a smartphone we should be trying to reach them on a smartphone when there is this kind of emergency."

Although some Ventura County residents said they did not receive Monday's message, Kaufmann noted that by targeting such a sweeping part of the county, officials reduced the risk of even more residents enduring frantic, last-minute evacuations.

"One of the things we have noticed is that if we rely on one system, that fails," Kaufmann continued. "People aren't registered for some alerts. Cell towers go down. We used every single thing possible to get the word out so that every person who could be affected would hopefully get a warning in some way."

Officials in Los Angeles County utilized the same strategy, issuing at least four specific, geo-targeted alerts Wednesday, including mandatory evacuation orders, as firefighters chased another fast-moving wildfire fast encroaching on hillside homes. The Los Angeles Fire Department also used the system to remind residents to check for "up-to-date information" on its website.

So far there have been no reports of injuries or deaths as a result of this week's wildfires, in stark contrast to October's catastrophic fires. During those incidents, officials in Sonoma County, where 24 people died, were concerned about deploying such an urgent alert to massive numbers of people, and instead sent warnings through robocalls, social media, the Nixle system, and SoCoAlert, which only a fraction of residents had signed up for before the fires.

"It was not a negligent decision. It seemed like the best, most appropriate response at that time," Hannah Euser, spokeswoman for Sonoma County, explained at the time. "Half a million people would have gotten an emergency alert, many of them in areas not affected, and it could have been chaos."

FEMA refuted the claim that the alerts cannot be manipulated according to local needs, telling BuzzFeed News that "the alert originator has the option of providing geographic coordinates defining the area where the alert is to be targeted."

Months later, officials with the Sonoma County Fire and Emergency Services Department still contend they are reviewing the decision not to use the wireless alerts. On Nov. 30, in response to multiple BuzzFeed News requests for data on how and when residents were alerted, the department responded that the county is still "in the process of making some records" available online.

When asked if Northern California's emergency notification issues influenced Ventura County's decision to send the wide-reaching alert Monday, Kaufmann said that officials look at all past fires as learning experiences.

"We're fooling ourselves if we say we don't learn from other fires that happen," he said. "I do think the faster you get the notice out and get people out and on the road, then you don't have people trying to leave when fire equipment is coming in. When firefighters aren't using time and energy helping people getting into their cars and can focus on the fire leapfrogging from house to house, they are able to save more lives."

Still, about a dozen evacuees in Ventura County said they never received a blaring message on their cell phones or that it came late. Melissa Givner raced to save her horses after seeing an ominous orange glow climbing over the hill toward their suburbs and ranches. Ginger Moore said that she was informed that her apartment building was under mandatory evacuation via a text from a friend.

Kay and Al Berg decided to flee their now-destroyed house about an hour before the alert was deployed. Kay Berg said she found out she needed to leave after a live news alert on Facebook informed her the neighborhood was evacuating.

"We had about 45 minutes and the power was out, so we were running in the dark with flashlights trying to figure out what we needed," she said. "It wasn't until we were backing out of the driveway that we saw police."