When Linda Cox, then known as Linda Cranford, a smiley 18-year-old from rural Chickasha, Oklahoma, wanted to join the Air Force in 1971, she had to take two tests.

The first was a standard academic exam: math, writing, plus a practical section on machines and tools. Cox aced that test, especially the last part; growing up dirt biking with her brothers in West Texas, she knew all about fixing engines.

The second was a little different. The recruiter took Cox’s measurements — bust, waist, and hips — and then pulled out a camera to take a photo. “We have to see your legs,” he said, as Cox adjusted her skirt for the best possible view. The full-length photograph, body measurements, and aptitude test were reviewed; if they could stomach the altitude chamber, the top candidates became stewardesses on a general’s aircraft.

“I was a scrawny little thing,” Cox said to me over iced teas, her tan face crinkling as she laughed at her former self. Forty or so women tried to enlist with the recruiter that day, but only Cox and one other were chosen for the WAF, the Women’s Air Force. At the time, she wasn’t offended. “It was prestigious. Hey, cool — I get to fly! Everybody else got shuffled down to the Army.” Besides, she knew her dad, a World War II veteran, would be proud of her choice to serve; her older brother had already gone to Vietnam and her mom had worked as a code breaker in the Navy.

But from the beginning, she didn’t quite fit in. The majority of women joined the WAF for clerical or nursing positions. Not Cox. “We’ve never had a woman score so high on the mechanical test,” the recruiter told her. So instead of going to the secretary pool, she learned to operate a printing press at the prairie outpost of Grand Forks, North Dakota. One evening, while hanging out in the women-only barracks, her good friend Peggy McCormick handed her an advertisement for a job called explosive ordnance disposal (EOD). Cox had never heard of it, but the page said EOD was short volunteers and paid an extra $55 a month.

“Bet you won’t do that,” McCormick said. All she knew was that EOD was dangerous and somehow involved bombs.

“Bet I will!” Cox said.

“I dare ya,” McCormick said.

That’s all it took. The nation created its first female bomb technician on a dare.

Cox was done printing newspapers. She would make it through EOD School, survive the ridicule of narrow-minded officers and the unwanted attention of journalists and the women’s liberation movement. She broke every glass ceiling in Air Force EOD: first to lead her own unit, first to go to war, first to be awarded a Bronze Star, first to hold the highest enlisted rank of chief master sergeant.

Today, women are knocking down the last barriers in the U.S. military; on April 27, the Army announced that Capt. Kristen Griest will be the first female infantry officer. And Linda Cox is still at work at the age of 63, as a contractor disposing of dud munitions around the world.

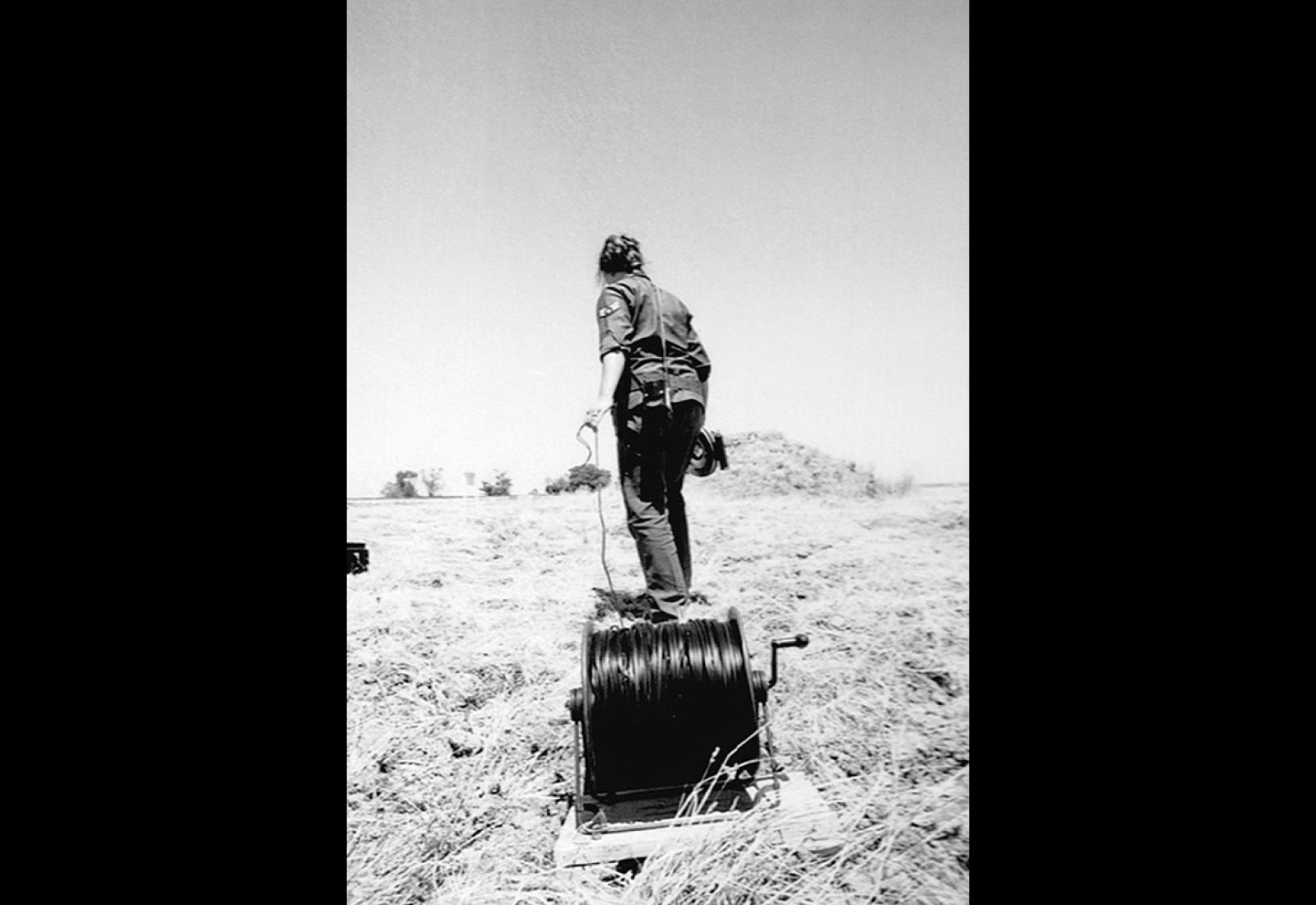

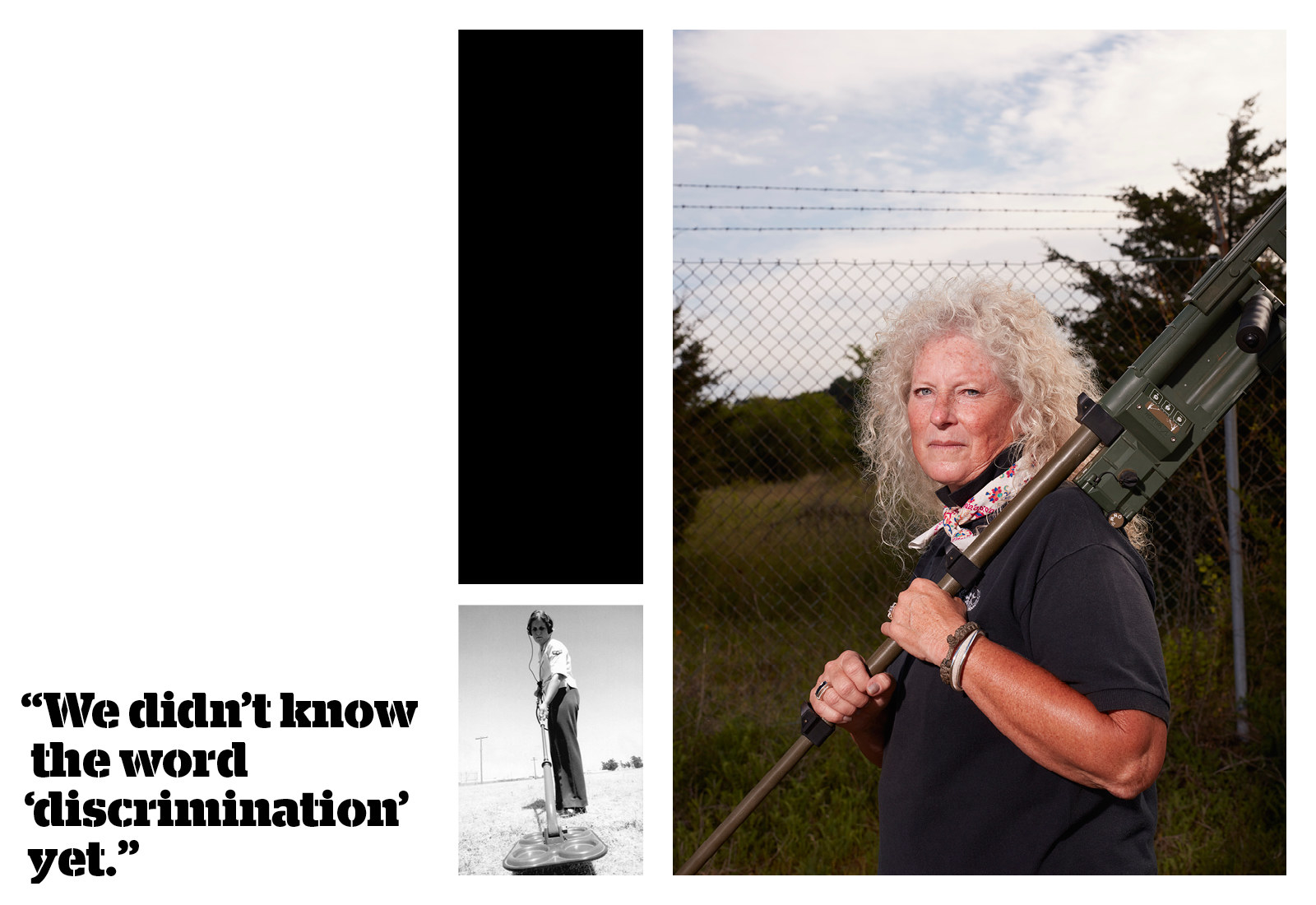

In April, I met up with Cox at the decommissioned Savanna Army Depot, a stripped railhead and bunker complex on the eastern shore of the winding Upper Mississippi River. From the air, the old post looks like a moldy checkerboard, overgrown with trees. She had only been on the job a few weeks, leading a crew using a ground-penetrating radar to make 3D maps of metallic signatures under the dirt; anything that looks like a mortar or grenade or bomb has to be dug out and blown up. The scrawny girl has toughened up from decades of range work, her formerly dark curls weathered into a startling gray shock of Einstein hair. I had been warned by Tim Callahan, a fellow EOD technician who rose through the ranks with her, that Cox was “always a lady, but a tough old broad.” Warm but firm, genteel but not gentle, she shared her thoughts — on her career fitting in as an “EOD guy,” women in combat, and what lies ahead — with me in an easy Texas drawl.

For her part, she sounded a cautionary note for military women today, that significant challenges still lie ahead for soldiers like Capt. Griest, and that her own path is not easily reproduced. The Air Force EOD community was tiny, under a thousand people. Breaking into that insulated elite is a vastly different proposition than cracking the massive infantry representing a wide cross-section of America, enlightened and not.

“I’ll tell you what, I had it easy,” Cox said. “These gals coming up, going into combat units now, they’ll have it a lot harder than I did.”

It was an administrative oversight that allowed Cox to attend EOD School at all. Her first sergeant, the traditional overseer of welfare and discipline in all military units, helped her fill out the application form, but almost immediately the training headquarters sent it back, saying that she had made a mistake. The "F" box was checked, rather than the "M." Certainly it was a man applying? Cox resubmitted the form, but it was returned again, indicating her name was misspelled. She meant “Larry,” not “Linda,” right?

Cox sent in the paperwork a third time. She and her first sergeant had researched the obscure regulations guiding her application, and nowhere in the job description were women barred from joining. Until then, the Air Force didn’t have to explicitly exclude women. “They just never even thought about it,” Cox said

Like an IRS audit, the application came back with additional instructions: Cox had to go to the base hospital, where under the watchful eye of a doctor she would take a fitness test to prove she could carry 100 pounds. This was outside of regulations; back then, men had to pass no such physical. Unsure how to administer the test, the medical staff loaded a bucket with rocks and bricks, which Cox lifted and carried a few steps. The Air Force was out of excuses.

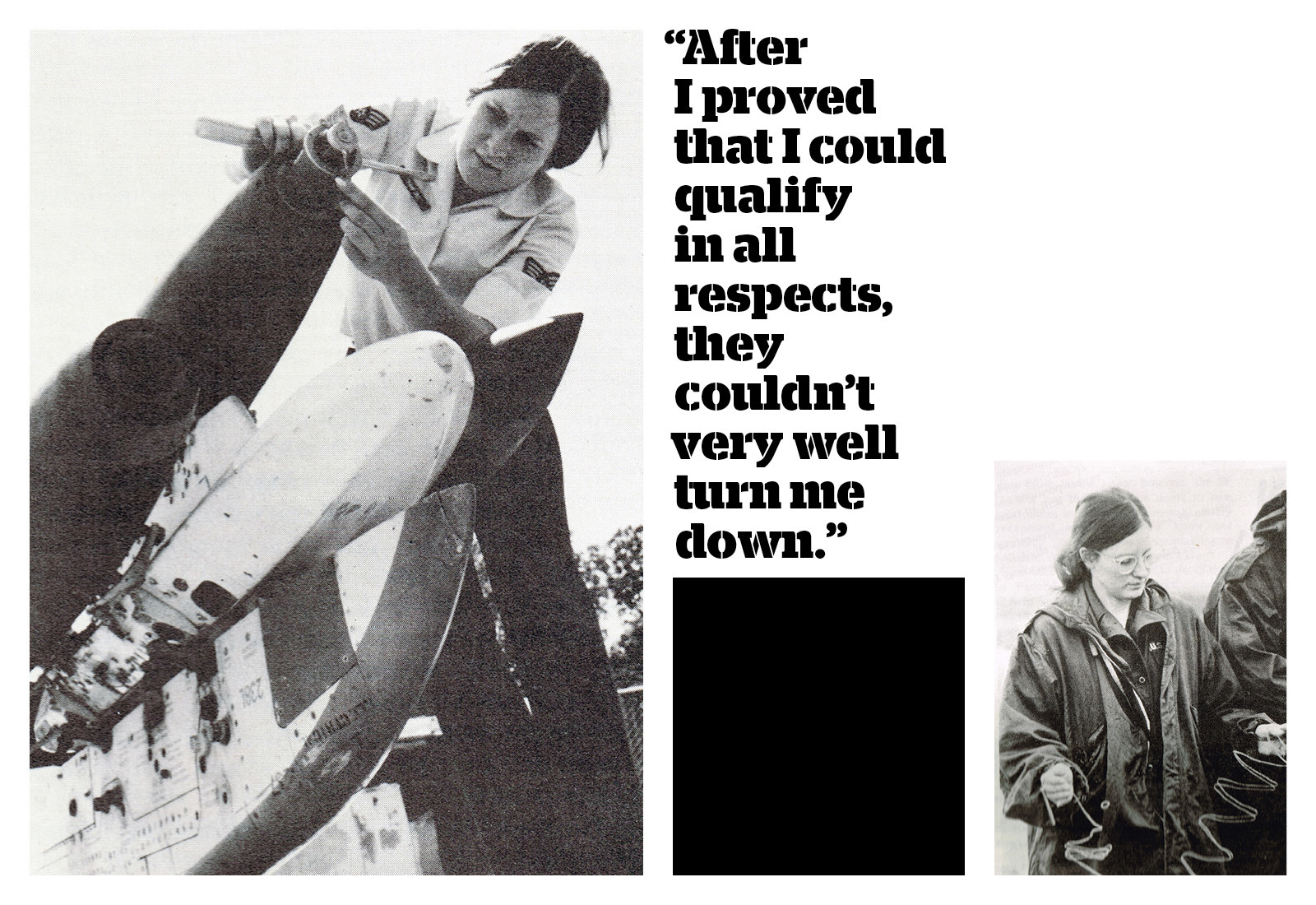

“After I proved that I could qualify in all respects, they couldn’t very well turn me down,” she said to a newspaper reporter at the time.

No one told Cox she was the first female student until she arrived at the EOD School at Indian Head, Maryland, in January 1974. The commanding officer looked confused when a woman appeared at his desk to report for duty in her dress blues. By way of welcome, he said only “Don’t go to the Sportsman,” a notorious dive bar outside the gate. Cox would begin class wearing a men’s green fatigue shirt and pants — the closest utility uniform for women consisted of a large, light-blue denim skirt — and jungle combat boots that had to be special-ordered, her small feet traced on a sheet of paper.

The EOD School is known as one of the toughest in the U.S. military, a physically demanding high-speed mental grind with a graduation rate as low as 15%. Over six months, students learn a bewildering variety of tasks. Demolitions. How to clean up liquid mustard agent. Rope tricks to winch a 500-pound aircraft bomb out of a hole. The use of mine detectors and stainless steel wrenches activated by coiled springs. Plus the safest way to disarm thousands of types of munitions: grenades, rockets, mortars, nukes.

I can attest that the school is grueling for anyone (I attended nearly 30 years later), but Cox had to endure personal hazing as well. A few World War II– and Korean War–era instructors promised her she wouldn’t graduate. During rainstorms, her ordnance practical exams would invariably be underwater in a crater, or on the far side of the range, so she had to lug her equipment the maximum possible distance. “Your problem would be way over there,” she said to me, pointing to a building hundreds of yards away, “but you had to carry everything with you in one trip. I’ve got ropes around my neck, I’ve got a 20-pound sledgehammer, I’ve got the toolbox, and this one officer wrote me up, ‘Linda can’t handle this field. She can’t do it. It’s obviously not for her,’ because I put my toolbox down and switched hands.”

The male students worked in the water and carried heavy loads as well, but special scorn was saved for Cox. “Some of the Navy guys, the Marine guys, they were embarrassed for me being there,” she said. One anonymously left a newspaper article on her desk, about a girl who wanted to join the Boy Scouts. “I had people poking me in the chest saying, ‘If you make it through my class I’m retiring!’ I would call home crying, ‘What did I do?’”

Cox found support from her fellow classmates, who were nearly as powerless — and just as desperate to pass — as she. One was Donald Wetekam, an Air Force lieutenant who went on to become a three-star general and the nation’s highest-ranking EOD officer. “We knew Linda was the first woman,” Wetekam said. “She was mildly interesting at first, a minor celebrity. But then you get down to work, and cooperate to graduate.”

She could have quit and returned to printing base newspapers, but Cox was succeeding; Over the entire course, she would fail only one test. More important, she was captivated by the job from the first moment she plugged a blasting cap into a block of TNT. We can really blow things up? she recalled thinking, as if she was getting away with something. She could put explosives on anything — a pile of old land mines, cardboard boxes, a wooden table — and it would cease to exist and “turn into air.” It was a revelation.

The Vietnam War (and its related anti-war activism) winding down, Cox faced few external rebukes, but her bid to make history was almost upset by an unlikely source: the National Organization for Women. Cox still isn’t exactly sure how they found her, but guesses she was spotted at the 4th of July parade in Washington, D.C.; Cox rode on a float, a massive Nike Hercules missile, and waved to the crowd. Days after this public display, Cox says NOW contacted the EOD School, searching her out. They wanted her to stand up, speak out, proclaim herself a feminist, and become a poster child for their cause. “Look what you’re stirring up,” one instructor told Cox, when giving her the news. It was part of the feminist movement’s campaign to identify new positive public role models for young women, but that’s not how Cox took it; she felt threatened by the attention. “I didn’t want these people interfering with what I was trying to do,” she said of NOW.

“In the military, you can’t express those kinds of opinions,” she said. “And anyway, I thought, that’s not why I’m doing this. I’m just a gal, one of the guys, I came by it honestly, I grew up with brothers. I didn’t know I was doing anything different.” Cox didn’t want to be a maverick or a spokeswoman. She didn’t want to be first. “I was Blue,” she said. Air Force Blue. She just wanted in.

Cox adopted a strategy that would serve her well throughout her career. She shut out distractions, including NOW, and got to work. Competence would see her through, she decided, and a sense of humor to defend against bullying. Out on the demolitions range, to indicate where students should urinate, the instructors nailed two signs on opposing trees: “Men” and “Linda.” Cox pulled out a funnel painted gold that she was given for the task and happily complied. She could laugh because her classmates and just enough instructors were on her side. For every Navy officer who would browbeat her, there was someone ordering her special combat boots, or a first sergeant submitting her application three times.

In the end, even the commanding officer came around. When she graduated in August of 1974, he personally pinned Cox with a special EOD badge. This presentation of the crab, as the insignia is colloquially known, is the highlight of the ceremony for every student. But in Cox’s case, the badge itself was unique. It had a large brooch clasp and was stamped “sterling silver” on the back. The officer told Cox that it was one of the original EOD badges created soon after World War II, the very first off the assembly line, just like her.

The hazing stopped once Cox wore the crab. The infamous training course is a universal crucible; survive and you’re in the club. “I immediately had a thousand brothers,” she said. But it is also true that Cox helped the transition by seeking to integrate herself into the existing culture, rather than act as a change agent.

Explosive ordnance disposal has always been an insulated tribe: few practitioners, classified methods, an air of mystique. Plus the famous brash ego presented to all outside the clan. Within the unit, though, display that same attitude and you’ll be quickly knocked down to size. Notoriety is punished, making Cox’s quiet, hardworking attitude — “I’m no better than the guys, but they’re no better than me” — a natural fit. By never claiming that she was different or special, Cox was the model young EOD airman.

She even adopted the language. The Women’s Air Force program wasn’t officially abolished until 1976, but Cox rarely used the term herself. “I still consider myself an EOD guy,” she told me. “We’re all EOD guys. It means we’re all in it together. When I see another woman, she’s an EOD guy. It’s a term of endearment.”

Cox was sheltered from the media while a student, but once she arrived at her first assignment, McChord Air Force Base outside of Seattle, she was followed by reporters, awed that the EOD Man could be a woman. This lasted until one journalist asked what part of disarming bombs was hardest for a lady. Cox answered: “Keeping my manicure.” The Air Force stopped the interviews, and the EOD tribe protectively closed ranks around her. “I was just being a smart aleck,” she said later. She was sick of getting asked, though she considered the answer the truth; everyone who knows Cox mentions her perfect nails, and I can report Sunday is still “nail night.”

After a quick tour in western Washington, Cox was assigned to Travis Air Force Base in California, and then Bagotville, a nuclear weapon storage depot north of Quebec City in Canada. She was the only woman on base, and there she met and married a bomb maintainer named Paul Cox; the joke went that he built the nukes and she took them apart. Paul and Linda Cox would serve together in Albuquerque, England, and Germany, classic Reagan-era Cold Warriors. By the late 1980s, they settled in San Antonio, where she led a unit of a dozen EOD technicians at Lackland Air Force Base.

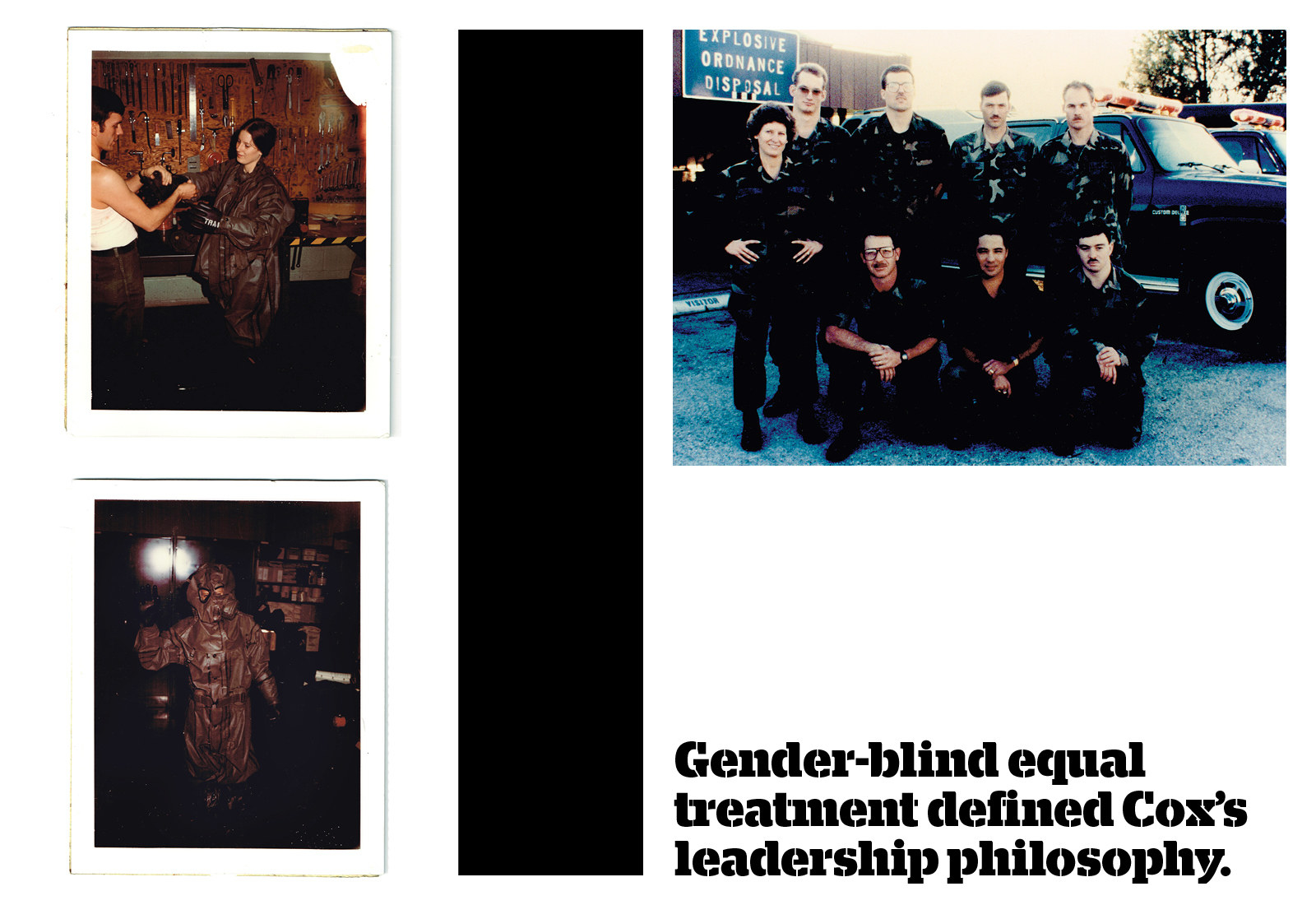

The hazing was long gone, but sexism occasionally appeared as she rose through the ranks. Rumors spread that she had an advantage as the first woman, despite the military’s reputation for merit-based promotion. Others complained about the possibility of working for a woman at all. Cox was a different kind of boss: She would make her troops stay home for wedding anniversaries or wives' birthdays. But her old friend Tim Callahan said he typically saw her airmen defend her when she wasn’t around, and when he first had a young woman work for him in the early 1980s, he called Cox for advice. “Don’t treat her different than anyone else,” she said.

Gender-blind equal treatment defined Cox’s leadership philosophy. She felt pressure to be an example, not a mentor, and didn’t intentionally take female subordinates under her wing. Tina Stetson worked for Cox at Lackland in the late 1980s. “She wasn’t an inspiration,” Stetson said. “She was my boss.” Nor did it matter to her that Cox was the first. “Do you see any tits on my crab?” Stetson would say. Stetson eventually retired as a senior master sergeant and is now the military liaison to the Department of Energy at the Sandia National Labs in Albuquerque, where she develops the procedures to disassemble U.S. nuclear weapons.

Cox’s cold war finally turned hot when Iraq invaded Kuwait. In the summer of 1990, she was at the peak of a typical military career: almost 40 years old, a master sergeant running her own bomb squad, eligible within months for retirement with a full pension. When orders arrived to deploy to Saudi Arabia for the new Operation Desert Shield, some sexism lingered; the chief wasn’t sure if they should ask her to go, but the first guy he called gave an excuse to get out of the assignment.

“I would have been mad if you hadn’t asked,” Cox told him. “Of course I’ll go. It’s where I want to be.”

Cox deployed to King Fahd Air Base outside of Dhahran, near Bahrain and the Persian Gulf. It was nothing but an empty concrete airstrip when she arrived; in the tent they built for an operations center, they used a safe as a chair. During the day, Cox prepared for the invasion, and at night she watched dueling Iraqi and American missiles arc overhead.

Cox spent most of her time alternating shifts in the command post, an agonizingly boring assignment. With little to do but wait for the war to start, the command post staff had set up a mobile antenna to pick up scraps of Armed Forces Radio. One night Cox caught an address from President George H.W. Bush. He sounds distraught, she thought, questioning whether he did the right thing, American boys and girls in harm’s way.

Cox felt a bond with the Bush family. EOD technicians have augmented the Secret Service for decades, searching for hidden explosive devices anywhere the first family may travel. Back in Texas, Cox had served on many such missions, in the president’s retirement home and hunting retreats. Barbara Bush was known as a particularly pleasant first lady to work for, baking cookies and passing out Christmas cards. Even then, Cox was often the only woman on the detail, and so she became a familiar face; Barbara smiled and waved whenever she spotted her.

Listening to him on the radio, Cox felt protective for her president and immediately wrote him a letter. “I said, ‘Sir, don’t even think about it,’” she reflected. “‘We’re proud to be here.’” She put the letter in an envelope, addressed it “White House,” and placed it in the outgoing mail bin. Cox thought no more about it until she received a handwritten letter back from Barbara, thanking her for the note and saying that the first lady had personally delivered Cox’s letter to George that evening. “In-flippin'-credible,” Cox said; she kept the letter and framed it.

Many Gulf War veterans, Cox among them, display a pride in their service with a purity that has been lost in the twisted post-9/11 mistakes in Iraq and Afghanistan. They went to defend a country and won. “It probably helps that they were grateful for us to be there,” she said.

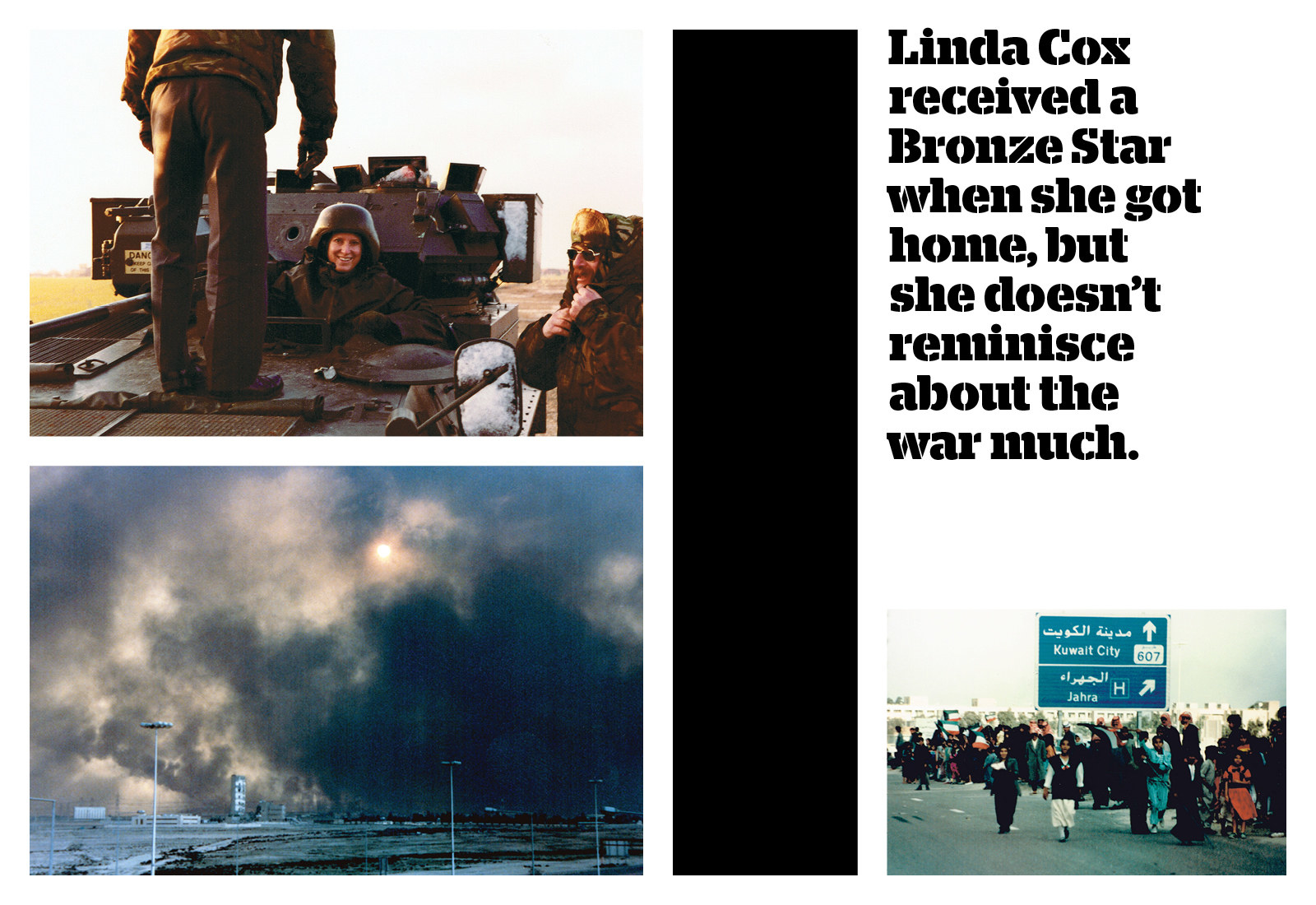

When the ground campaign of Operation Desert Storm finally commenced in January of 1991, Cox volunteered to lead a small team north into Kuwait to survey several classified airstrips. Close on the heels of the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions, their mission was the determine whether the runways were cratered beyond repair or usable for American aircraft. Cox, another EOD technician, and two intelligence airmen snuck into the country in an armored Humvee. As they drove, the sky turned black, the oil wells burning like inexhaustible space-shuttle rocket engines nosed into the ground. Throughout the desert, bits of planes and tanks stuck out of the sand, buried by retreating Iraqi soldiers. The streets of Kuwait City were nearly deserted, with smoldering vehicles and ammunition littering the ground. In the beds of pickup trucks, they found dead Iraqi soldiers intermingled with the dead civilians they had used as human shields, rocket-propelled grenades stashed under floorboards. Cox and her team checked wrecked tanks for booby traps. When hiding locals realized they were Americans, they came out in a crowd, seemingly from nowhere.

Women in flowing flowery dresses approached Cox. They smiled and had their fingers up in V-for-victory signs, but the stories they shared were horrific. Iraqi soldiers had entered their homes, put the women on the couch and raped them, lined the men up against the wall and shot them, there in the living room. One old man in a white headscarf and a long blue robe broke all decorum and lay down at Cox’s feet. She tried to stop him without committing a cultural taboo herself, but over and over the old man said “American hero” and kissed her boots.

Cox was overwhelmed. “No, you are the hero,” Cox said to him. The stories of the “Rape of Kuwait” were all over the media: eyes gouged out, ears cut off, acid burns, skulls sawn in half, systematic execution, and sexual assault. “You stayed here, you fought Saddam. We Americans think you are the hero.” And the old man’s face lit up.

“That’s the best thing I’ve ever said to anyone,” Cox reflected as she told me the story. Her eyes went red and filled with tears. “I can’t talk about this without getting chicken skin,” she said, and paced about the room, grabbing a nervous drink of water.

Linda Cox received a Bronze Star when she got home, but she doesn’t reminisce about the war much.

“This stuff would murder my sleep if I gave it much thought,” she said, and then she politely changed the subject.

The Gulf War may be 25 years gone, but some things haven’t changed. Americans are still fighting in Iraq, civilians are still caught in the middle, and Linda Cox is still working as an EOD guy.

Just south of the Savanna Army Depot, her latest project, is the small Mississippi River town of Clinton, Iowa. Cox loves baseball, and we took in a Single A minor league game at the small stadium dug up against the flood levee. The Cedar Rapids Kernels whipped the hometown LumberKings 9–0, but neither the score nor the chill breeze off the water nor the lack of alcohol (no sales on Sundays) dimmed Cox’s enthusiasm for the event, as we chatted on a sunny spring afternoon about her process of enlistment, bust measurements, and leggy photos.

“It’s flippin’ crazy now to even think of that,” she said, “but we didn’t know the word ‘discrimination’ yet.”

The Iraq War and her job endure, but American society and the military have changed dramatically since Cox joined up in 1971. In Women's Air Force basic training, she said, they marched around the drill pad, but didn’t run the obstacle course or fire any weapons. “We did modeling things. We painted our nails,” she told me.

“No, you didn’t,” I said.

“Yes, we did,” she said. “Funny, huh?”

After the Gulf War, Cox was promoted quickly, reaching the pinnacle of chief master sergeant in 1994. She would become a respected voice within the larger EOD community, a leader on matters of policy, as a manager at Air Training Command. Her colleague Lt. Col. Greg Mittelman remembered, “She didn’t wave her hands or beat on a podium, so people didn’t realize how much she was soaking up. She’d say ‘aw shucks’ and bury her toe in the dirt like back on the ranch in Oklahoma, and then come up with a better idea than any of us.”

Other military women were also making great strides at the time, moving into more obvious combat roles. Desert Storm was a watershed. The first war since Vietnam, and the military won while women served in non-administrative, non–skirt-wearing-stewardess jobs. Only after the Gulf War were women finally assigned to Navy combat ships, or allowed to fly fighter jets and attack helicopters.

The early 1990s, however, was also the era of the Navy Tailhook sexual assault scandal and the Anita Hill hearings. Behavior previously deemed acceptable, or at least tolerated through silence, was finally being recognized as the sexual harassment it had always truly been.

Cox remembers those times, especially the hard-drinking EOD parties. “They kiss each other in the ear. This one guy, every time he got drunk, he wanted to flash you. But he did that to everybody.” It was against the law but hardly enforced. Cox’s strategy was to stay above it and not partake; she still rarely drinks, and she left those parties early.

Only occasionally was the harassment personal. In the late 1980s, one old chief suggested Cox and Tina Stetson and three other female EOD techs join him for a special mission, an all-women clearance of a remote bombing range. “What did he think,” Cox said, “it would just be him and the girls? We’d wear pink cammies? I thought, You jackass. I politely said no. Tina and the other gals told him where to stick it.”

When Cox considers women joining the combat arms today, it is these types of incidents that give her pause. Will new female infantry soldiers be able to tell their superiors to stick it when they suggest all-women platoons as a gimmick? And in day-to-day military life, joining a small obscure EOD unit of 12 is less intimidating, less disrupting, than joining an infantry company of 150. Once Cox entered the EOD brotherhood, once she graduated and earned her crab, the hazing stopped. She fears that won’t be true for the current trailblazers, and that the military won’t have the common sense to keep women out of places where they’d be in danger from their peers.

Cox says policymakers are too focused on the desired end state, without putting enough attention on the actual women, real people, who will fill the units. “Not everything is for everyone,” she said repeatedly. For Cox, freedom and choice are paramount. Women should not be barred from any job, or pressed into one, either today or in some future theoretical draft. “Let them volunteer, but don’t change the standard. Don’t rewrite the book,” she said. “Select whomever you want, let them go through school, and that’s where they’ll wash out.” In Cox’s estimation, success in an intense military job — EOD, the infantry, SEALs, Special Forces — is about the motivation and personality of the individual, not their gender, and any mention of numbers or statistics, anything that smells of a potential quota or set-aside for women, spins her up like a top. “They’re trying to make the widget fit before they have the hole cut,” she said.

It is worth noting how much the public conversation has changed: not whether women are capable of doing the job, not whether they are strong enough to throw BDU-33s in the front-end loader, but what standards to use for men and women, and how to best integrate the units. Cox's career contributed to that evolution. “Just last week I used Linda as an example,” said Wetekam, Cox’s former classmate, who is now an executive at AAR Corp., a leading aerospace and defense firm. “I was at the Rotary Club, and they knew I was a retired general, so this one gentleman starts complaining about women in combat. And I was trying to explain to him, women have been in combat for decades. Get with the times. They’ve been in bomb disposal for 42 years. Bomb disposal! The whole current conversation is a red herring.”

If the integration of women into EOD units happened by accident, the Army is more deliberate today, using a “leaders first” model. Female officers will set the example, provide cover for their lower-ranking female enlisted soldiers. It is the inverse of Cox’s experience; she was left to make her own way. Capt. Griest, the first female infantry officer, will have the rank to fend off the discrimination, but also the spotlight, and expectations Cox never had. After a few press conferences following her graduation from Ranger School, Capt. Griest has declined interview requests, a choice Cox understands. Until we met in April, she had not spoken to a journalist in decades.

Cox is divorced now, though she’s still “best buddies” with her former husband, and they live in the same town, close enough to meet for dinner and a movie. They consciously chose not to have children; it didn’t fit with their dual military careers. “We abuse our families because we want to be with our friends,” she reflected. “And it’s harder to stay home than it is to go.”

A lifetime ago, Cox shrugged off NOW’s advances. And yet, in the end, she embodied the independence and agency they advocated, ahead of the times.

For the last decade, Cox has been a consultant for CH2M Hill, a large environmental and engineering firm with contracts around the world. In that capacity, she has traveled to Wake Island dozens of times as a technical adviser for battlefield cleanup; human remains still wash up on the beach and bombs peek out of the ground like mushrooms.

But recently, after a double knee replacement, her range work has begun to slow down. Joints shot, old injuries from her days as an amateur stunt actor in Albuquerque — until their agent ran off with the money, Cox was part of a troupe that staged bar brawls to entertain patrons between music acts. Not to mention years of dirt bikes and demolition work, of course.

At the Savanna Army Depot, the cleanup is conventional. Cox and her team are finding ordnance over a century old, white phosphorous grenades and Stokes mortars. “It’s really kinda fun,” she said. “I can’t wait to start digging. The World War I stuff is just fascinating.”

A pickup truck has replaced her special-order jungle boots. To find the munitions, she has ground-penetrating radar instead of a Vietnam-era mine detector. But some things don’t change.

“I’ve been hooked since my first smell of C-4.” ●