ISTANBUL — Outside, winter’s chill grips the grey, war-ravaged city, a nightmarish landscape of bombed-out buildings, piles of rubble, and smoldering trash frequently strafed by screeching warplanes or regime helicopters loaded with crude bombs made of dynamite and metal shards.

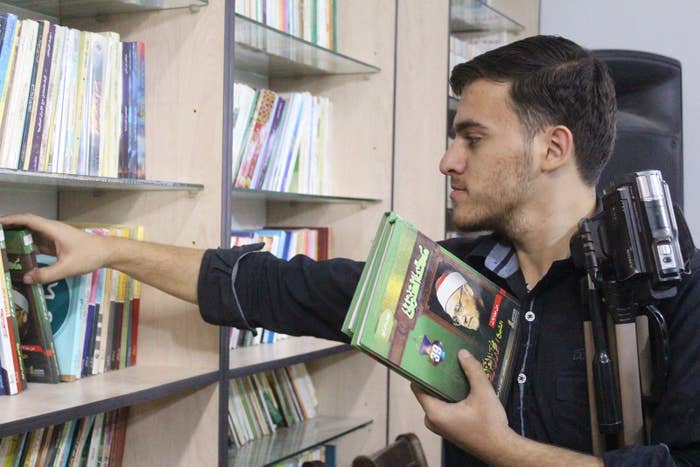

But inside the basement of a residential building in the Damascus suburb of Daraya, the world beyond Syria’s borders opens up. It is a place of learning and ideas, with books salvaged from the wreckage outside and cobbled together into a makeshift library of 15,000 volumes. A photocopy of an old history book, a shelf full of children’s stories, and self-help books by Tony Robbins, sit alongside a J.M. Coetzee novel, a volume of Islamic scholarship, and slim editions of Arabic poetry by Mahmoud Darweesh or Nizar Qabbani. They are read by candlelight during lengthy power outages or at the war front by rebel fighters.

“With all the destruction, we need to hold onto our culture,” said Ahmad, one of the main organizers and the spokesman of the library. Speaking to BuzzFeed News over the course of weeks of interviews conducted over a dotty Skype connection, he asked that his last name be withheld for fear of regime reprisal against his family.

Syrian opponents to President Bashar al-Assad have been widely derided as extremist jihadis hungering to establish a puritanical Islamist regime. Even members of the U.S. Congress say the moderate opposition to the Damascus regime has been supplanted by sectarian extremists such as the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda’s Syrian affiliate.

But interviews with half a dozen fighters, photos, and video footage from the Daraya library east of Damascus paint a different picture of Syria’s uprising. They suggest the hopes for progressive social change, raised by the largely peaceful 2011 uprising against the Assad regime, have yet to be completely quashed.

“Despite what people think of us, we are people who have demands and a message to deliver,” said Omar Abu Anas, a 24-year-old former university student turned rebel fighter who frequents the library. “When we were attacked, we defended. Despite your calling me a jihadi, I’m Free Syrian Army and I want to bring down the regime to build a new government, to live in a free society.”

Daraya, a stronghold of moderate Syrian rebels opposed to both Assad and ISIS, suffered a brutal assault at the hands of regime troops and militias in August 2012. Shortly afterward, the government attacked again, prompting some men in Daraya to take up arms; they eventually came under the banner of the Free Syrian Army. The government responded in late November 2012 by putting the rebellious region under siege.

As the war dragged on, life in Daraya severely deteriorated. Tens of thousands fled for other parts of Syria or abroad. Regime helicopters and warplanes targeted rebel fighters as well as civilian homes, schools, and hospitals. Rummaging through the wreckage, fighters and volunteers came across books in danger of being smothered in the mud and rain or turned into tinder. “Book collections were getting destroyed, many were getting destroyed,” Ahmad said.

“We started collecting books from destroyed places,” Ahmad said of the efforts of around 40 people, many of them college students who abandoned their studies because of the war, at the end of 2013. “From houses that had libraries. We would go under rubble and get books. We would place them outside, collect them, and put them in cars and then moving to the libraries.”

Thus the Fajr (Dawn) library, as it is known unofficially, was established, the city’s first-ever free library. During stretches when it’s not closed because of bombing, it even keeps regular hours: 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily except Fridays. About 25 people a day tend to visit.

Many joined the effort to put the library together. Abu Majed, an FSA fighter, loved books. A third-year literature student before the war, he created a system for organizing the library, dividing them by category. His work had been completed for two months when Abu Majed died in a bombing on one of the fronts in 2014.

Though few women come to the library, many of the men who do borrow books do so for their wives, daughters, and sisters. Some visitors know exactly which books they seek. Others browse the titles. When they can’t find what they are looking for, the librarians search the internet for a download.

Among the most sought-after titles: The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey.

Volunteers reach out to book collection owners and gather the books from abandoned apartments. Daraya is a war zone, and doors of apartments are blown open. When possible, they grab the books and mark them with the names of the owners, or call relatives and seek permission.

“These books belong to the people of the city,” said Ahmad. “To teachers, arrested guys, some who left. After this war is over, owners can leave the books with us or take them back if they mean something to them.”

The books helped ease them out of their misery. “Little by little, things got better,” Ahmad said. “We attended lectures, read books, and then came together and summarized and discussed these books.”

One of the most popular titles in Daraya is Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, about a young Spanish shepherd who pursues a dream that takes him all the way to Egypt in search of a buried treasure and traces his adventures along the way. Ahmad, formerly a civil engineering student at Damascus University, says it’s his favorite novel, a welcome escape fantasy for those trapped in a war zone.

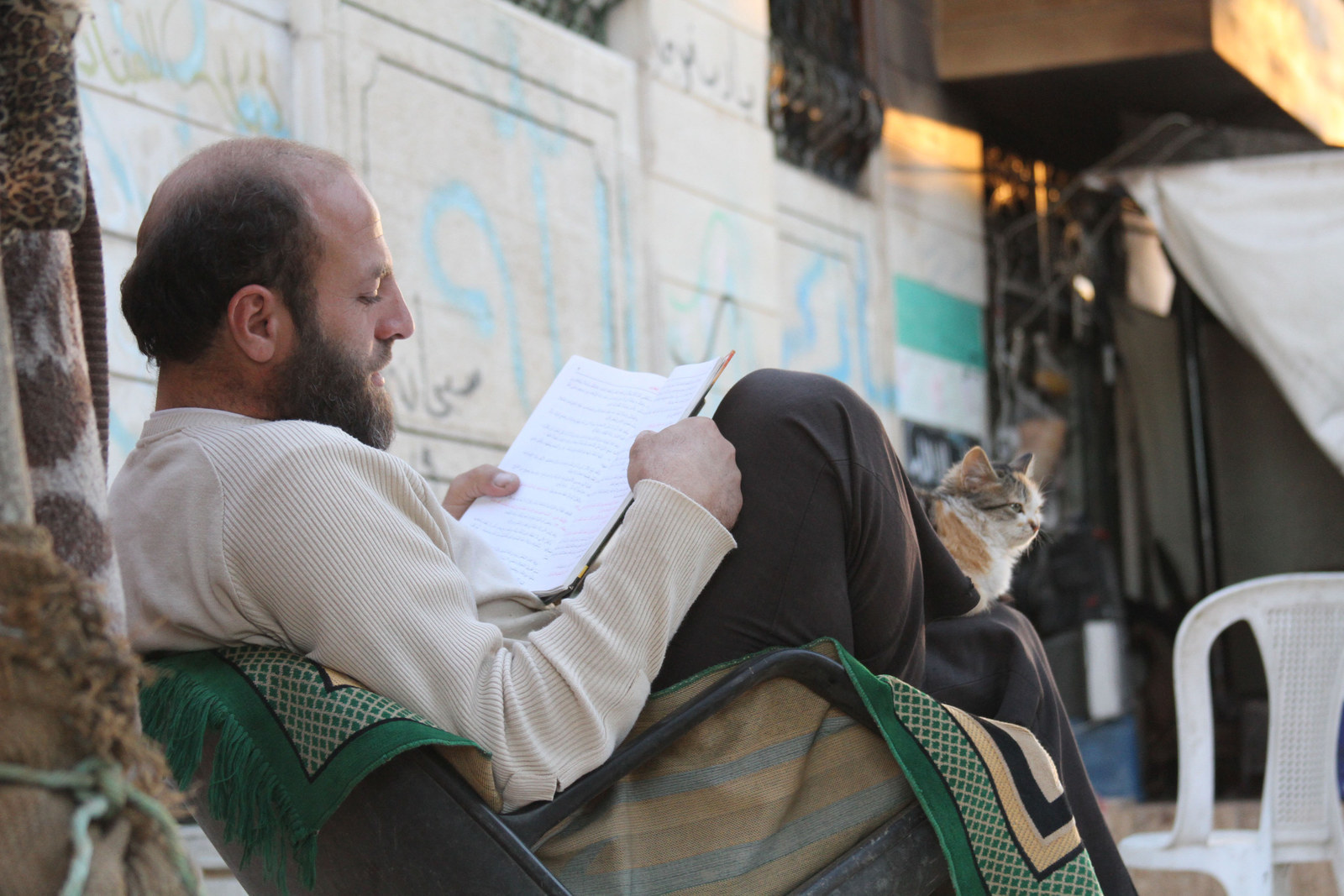

Books have helped fighters facing daily threats of death at the front cope with their realities, reminding them why they persist. Ayman abu Al-bara’a, 23, ended his economics studies at Damascus University in 2012 to join the FSA, a member of the Muwahida brigade. He reads everything from books by Islamic scholars to Arabic translations of American self-help books. Among his favorites is al-Qawqa’a by the Syrian writer Mustafa Khalil, about life and suffering inside Assad’s prisons. He’s read it twice.

“Despite all this destruction and all the circumstances we live in, we haven’t abandoned knowledge and learning”

“Despite all this destruction and all the circumstances we live in, we haven’t abandoned knowledge and learning,” he said in a Skype interview. “We borrow books and read them at the front. We are living in a besieged city. We might be under siege for years. So books are our greatest portal to knowledge.”

The organizers hope that the library can contribute to helping build a real democracy once the conflict is over. In Assad’s schools, Syrians read a social studies book that encouraged subservience to the government. Photos of Assad and his dictatorial father Hafez graced the first pages of every school book taught in Syria. “It’s like they were gods over us,” said Abu el-Izz, another co-founder of the library.

The former engineering student, 23, was severely injured in a recent bombing. The modest residential building that houses the library has been struck by regime warplanes repeatedly.

“Even in these circumstances, reading might help us after war,” he said. “If we have an educated generation, then we’ll achieve what we’ve been working towards. If we have an ignorant generation, then there’s no point for what we’ve been doing.”

Omar Abu Anas, the 24-year-old fighter, said he reads Muslim texts to glean lessons on the ethics of war but also anything political he can get his hands on, sometimes downloading PDFs onto his smartphone. “There are political things we need to know,” he said. “We want to build a new political system. We need to know international laws. We don’t want to just bring down. We want to build.”

Today, Daraya is witnessing a drastic increase in bombardment, and the tightened siege is making life more difficult than ever. The destroyed city’s library is quiet, but hopes to reopen its doors soon.

“We need to preserve what’s under the rubble,” said Ahmad.