For decades a sleepy, conservative monarchy, Saudi Arabia has been upended by its new crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, and has joined Iran and Turkey as a disruptive, ambitious, and unpredictable Middle East power that could lead the region into yet another war.

The 32-year-old prince, acting under the auspices of his father, King Salman, has launched a blockade against its neighbor Qatar, tightened a siege on Yemen, threatened to torpedo the fragile government in Lebanon, and sought to shore up a coalition against archrival Iran, which leads the Shia sect of Islam. Prince Mohammed — known to many as MbS — has also launched a radical transformation of his own kingdom, including sweeping arrests of dissidents, Islamists, and even wealthy royals.

“Saudi Arabia has become less predictable,” said Steffen Hertog, a Saudi expert and author of Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia. “MbS has dared to do necessary things that were taboo. He has also taken risks that many Saudis and Saudi-watchers see as unnecessary, notably in foreign policy. The risk of conflict with Iran, even if not intended, has probably increased.”

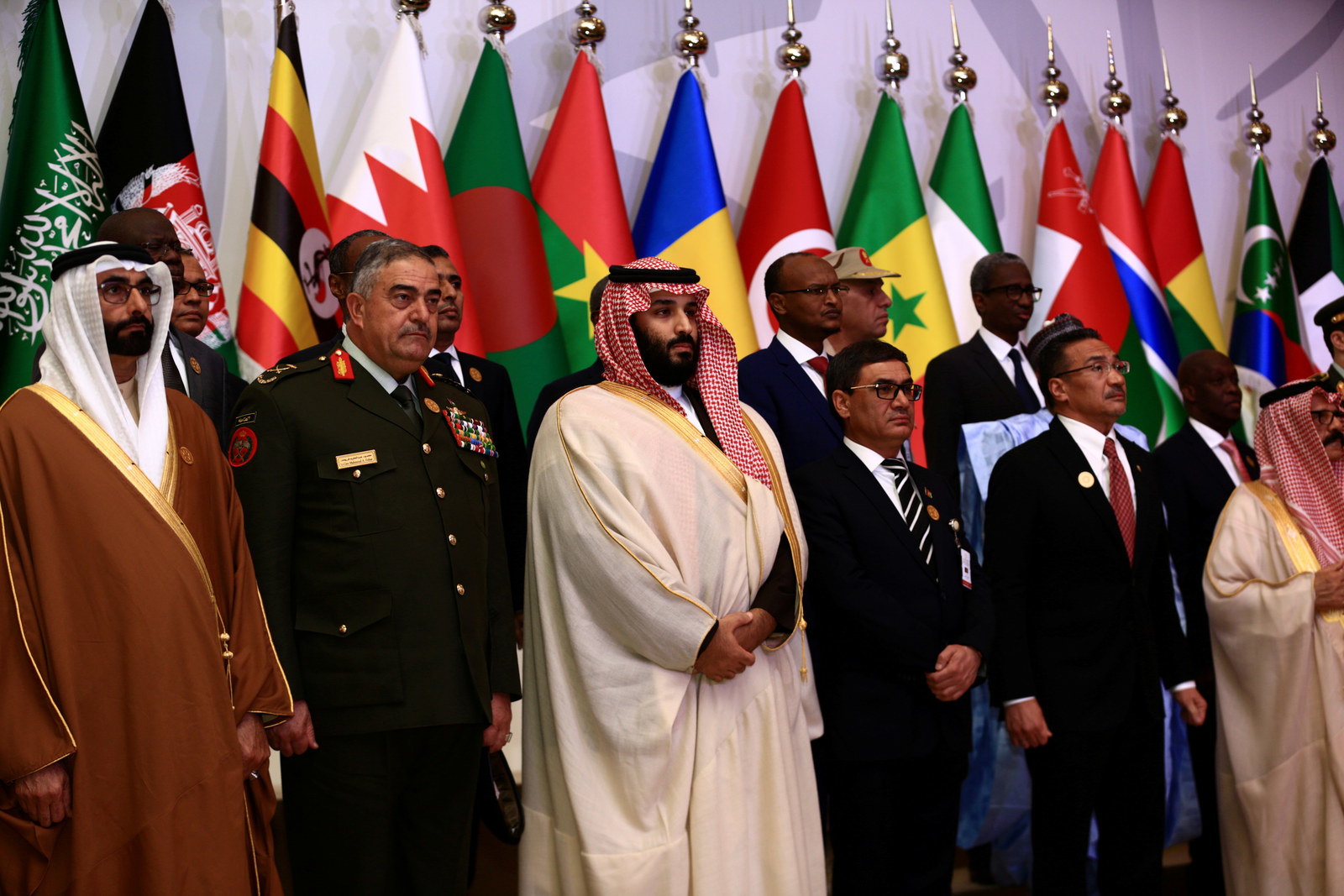

Prince Mohammed is not yet king but has already taken control of the ministries of interior and defense, as well as the national guard, the chairmanship of Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest energy company, and several other economic positions. On Sunday, he chaired the first-ever meeting of the Saudi-led Islamic Military Coalition of 41 Muslim countries.

“He is a unique character in the sense of the multiple powers he has,” said Madawi al-Rasheed, a Saudi scholar and dissident who was stripped of her citizenship and now teaches at the London School of Economics. “No young Saudi prince in the history of Saudi Arabia has amassed so much power.”

He is arguably the world’s most powerful millennial.

“He doesn’t have time for niceties. He just gets into business ... If anyone stands in his way, he takes them out.”

Those who have been closely watching the rapid rise of the hulking young man — at a beefy 6 foot 3, he towers over most of his contemporaries — are not surprised. “He has the personality of a bully,” said Ali al-Ahmed, an activist and Saudi dissident based in Washington, DC. “They say, ‘You cannot do that.’ He says, ‘Yeah, I‘ll do that.’ He pushed uncles and cousins out of the way. He’s able to fool even those in his firing range. It’s an amazing capacity. He removed people, he waged wars. He’s willing to push everybody else from his path and this is exactly what happened.”

Supporters of the Saudi regime say the crown prince inherited a situation that has forced him to act in a certain way. Saudi Arabia is hurting from low oil prices, widespread corruption, and a stagnant state-dependent economy. Previous reform attempts led by Saudi’s aging rulers faltered for lack of will or inertia.

“He is unpredictable only in the sense that Saudi was always predictable for doing nothing, so the contrast with the past is vast,” Ali Shihabi, executive director of the Arabia Foundation, a Washington think tank that is close to the Saudi leadership, wrote in response to questions from BuzzFeed News. “Also he is catching up with steps that should have been taken decades ago; as a result so much is happening in a short time.”

He added: “He is dragging the country — with Western critics kicking and screaming — into the 21st century.”

After charming investors and Western diplomats with plans to revamp Saudi Arabia by 2030, build a new city on the Red Sea, allow women to drive, and rein in the dreaded morality police, Prince Mohammed propelled himself into the spotlight this month with a series of dramatic moves.

He locked up hundreds of leading members of the Saudi royal family, including many partnered with international firms, on corruption charges, and then allegedly began shaking some of them down for cash. Among those locked up in the sweep was Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, an investor in Twitter and Citigroup, who was long regarded as a reformer.

Prince Mohammed upended the government of Lebanon by forcing its prime minister to resign, according to Western diplomats, while tightening a blockade on Yemen — all in an attempt to challenge Saudi’s archrival Iran. Last weekend, Saudi Arabia convinced the Arab League to further sharpen its conflict with Iran and its Lebanese ally Hezbollah at an emergency summit.

In many ways Prince Mohammed is seeking to fulfill a longstanding Saudi dream of leading the Arab world, and has sought to rebuild strong ties with the Trump administration as well as Putin’s Russia. But it’s the young prince’s war in Yemen, with images of starving children flooding airwaves, that has begun to catch attention in the region.

“Mohammed bin Salman is a dangerous person because his policy is the policy of a bulldozer as in Yemen, leading to the spread of diseases such as cholera,” said Nizar Makni, a Tunisian journalist specializing in international affairs.

The rise of the assertive young prince has upset traditional political calculations in the Middle East, quickly changing perceptions about everything from the possibility of another war to the price of oil. But officials, scholars, and activists question whether he can successfully leverage Saudi Arabia’s oil wealth and military power, as well as regional distrust of Iran, to win backers across the region.

“Saudi Arabia isn’t an appealing political model in any part of the Arab world,” said Neil Partrick, an expert on Saudi Arabia. “MbS may be creating the impression of an opening up, but this starts from a very restrictive and low base. On the one hand women are to be allowed to drive, and the religious police have been reined in; on the other there is a greater climate of fear due to leading figures in the ruling family, media, and business getting arrested.”

Inside the kingdom, the stories about Prince Mohammed are legion. Some of them are true, some of them half true, many of them apocryphal. But they all serve to burnish his image as a volatile young man in a rush to get things done his way.

There was the time the young prince got into a business dispute that wound up in court. He allegedly sent a bullet in an envelope to the judge to sway him. Or the time he allegedly dispatched the royal guard to grab a piece of land close to a hospital, leading to a standoff with local police.

He was once banished from the royal court, one insider said, as punishment for being too aggressive and too mean, refusing to abide by the decorum that governs life among the royal family. He’s the kind of guy who eats a lot meat, say insiders. Breakfast might be a small goat.

“He was not the quiet boy who sits in the back of the classroom,” said Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi journalist now living in exile.

Shihabi said such character traits convinced King Salman to choose him for leadership ahead of his older brothers. “Clearly, he exhibited a very strong personality and a youthful tendency to challenge rules and convention.”

Over the years, true or not, the tales have piled up. “What matters is the legend, and everyone believes it in Saudi,” said one Western diplomat focused on the Middle East, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

By the time Prince Mohammed was named Saudi Arabia’s deputy crown prince in 2015, and then next in line to the throne held by King Salman in June this year, he had already earned a reputation as a pugnacious young man with few scruples about how he got his way.

“There were all sorts of stories about his personal behavior,” said a Western diplomat who served for years in Saudi Arabia. “It was ambition. He had very sharp elbows. That’s what people thought of him, and they didn’t want to cross him. What you see is someone who is incredibly ambitious and is prepared to put heat on people to get his own way.”

Many supporters of the Saudi leadership find the tales circulated about Prince Mohammed amusing. Shihabi said the concept of banishment from the court did not apply in Saudi Arabia. “Its sounds colorful though,” he said. “These legends have developed and gotten more imaginative with every iteration as they pass through the rumor mill.”

Revamping Saudi Arabia’s oil-dependent, rentier-based economy and trimming waste is one of several major portfolios Prince Mohammed has taken on, and he has applied his distinctive style to the challenge.

“We have a case of addiction to oil in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on the part of everybody,” he said in an interview last year. “Oil should be treated as an investment, nothing more.”

He is arguably the world’s most powerful millennial.

Shortly before he was named crown prince, he called a meeting with the ministers of finance and planning and the central bank governor. Several advisers were waiting for him when he stormed in, according to an account provided to Ali al-Ahmed by a palace employee. Instead of shaking hands and greeting each of his elders, he got straight to the point, forgoing any of the flowery formalities and decorum that have shaped daily life in the Arabian Peninsula for centuries. He demanded brief summaries of each adviser’s recommendations, gave orders, and then promptly exited the room, leaving them flabbergasted.

“He doesn’t even say, ‘Hi,’” said Ali al-Ahmed. “He says, ‘You. What do you have? You. What do you have?’ He doesn’t have time for niceties. He just gets into business. He’s on some kind of turbocharge. He’s hyper and he wants to get things done and he doesn’t want anyone to stand in his way. If anyone stands in his way, he takes them out.”

Shihabi said Prince Mohammed “has an exceptional capacity for work and energy that exhausts all those around him.”

In public, Prince Mohammed has a way of bluntly questioning — or even mocking — Saudi habits that even dissident Saudis find refreshing. “When I enter a Saudi military base, the floor is tiled with marble, the walls are decorated and the finishing is five stars,” he said in an interview with Al Arabiya television in 2016. “I enter a base in the US, you can see the pipes in the ceiling, the floor is bare, no marble and no carpets. It’s made of cement. Practical.”

A show of his power and methods came earlier this year, when he replaced Mohammed bin Nayef, the former crown prince, now said to be confined to his quarters. Few had believed that bin Nayef — a powerful player who was supported by both the US and the mandarins of the Saudi security — could be toppled. “We saw [MbS] kissing the hands of bin Nayef,” said Ali al-Ahmed. “After that he was put under house arrest. MbS is a really good actor. It’s either shrewdness or trickery.”

Prince Mohammed’s boldness does have some limits, and he’s known for a certain erraticism. As deputy crown prince, he warned of impending austerity and taxation measures that proved tremendously unpopular. Once he was named crown prince, the proposals fell by the wayside. To his supporters, such flexibility showed political savvy.

“As he moves at high speed he has not lost his political antennas and realized that that those steps were hitting the middle class badly, so he reversed them,” said Shihabi. “He now realizes that the class to squeeze are the rich elites and not the middle and lower classes.”

The conventional wisdom is that Prince Mohammed’s moves and brashness are popular, and within a certain young Western-oriented middle class they most probably are. Khashoggi spoke of “whiskey liberals” who want to drink and have fun without worrying about the morality police storming in, and who are unconcerned about political freedom.

“He’s quite popular with younger Saudis, especially women,” said John Jenkins, who served as UK ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 2012 to 2015. “Seventy percent of Saudis are under 34, and he’s the first senior prince not to look like their grandfather.”

Some Saudis see him as a hero for his anti-corruption drive, for his support for women’s rights, and for giving Saudi nationalism a boost. He has been hailed by Saudis on social media. “After internal reform, we will be able to protect our regional interests as a sovereign and decisive state in the world,” said Mohammed Hussein, a Saudi businessman. “Mohammed bin Salman has a vision for the future of Saudi Arabia that may be long off, but the journey of a thousand miles begins with a step.”

But a climate of fear pervades in Saudi Arabia, especially after dissidents of all stripes were arrested in the months preceding the purge of royals. During an interview for this article, a journalist at a leading Saudi newspaper heaped praise on Prince Mohammed and said that he knew no one who opposed the crown prince. Minutes later he called back and asked that his employer not be mentioned for fear of imperiling his workplace in a story that might be less than effusive about the monarchy. Minutes later he called again, asking that his name not be mentioned, even though he had said only positive things.

“How can we know if people love someone or hate someone if we don’t have polls, if we don’t have elections, if we cannot talk in public about our opinion?” said Omar Abdul-Aziz, a Saudi student and dissident living in Canada. “Whatever the government says, people are going to accept that. Trust me. If tomorrow MbS said, ‘We like Iran,’ everyone’s gonna say, ‘Oh my god, we love Persian food.’”

“When his father dies there’s going to be no one else to blame but him if something goes wrong.”

Saudi defenders argue that the country is too politically polarized for the type of democratic reforms pushed by human rights activists. Shihabi said that Prince Mohammed possibly silenced many different groups with extreme demands, perhaps to the benefit of ordinary people. In the early 1990s, women activists tried to drive in violation of rules, and conservatives raged and prompted a crackdown. When Prince Mohammed announced women would be allowed to drive, there was barely a peep.

“That is a result of intimidation that kept these zealots quiet,” Shihabi said. “Clearly he has intimidated a lot of people, and in this period when he has to steamroll rapid change that may not be a bad thing.”

Any domestic forces arrayed against Prince Mohammed are weak, with most of his rivals held in luxury prisons, keeping a low profile, or under house arrest. Civil society is fragmented after decades of repression and cooptation. Saudi Arabia has always been politically restrictive, and could yet become even more so under Prince Mohammed, who could be the dominant figure in the lives of Saudi citizens for the next half century. No one wants to cross him.

“He has a reputation as fierce, and many royals and commoner technocrats are afraid of him, especially after the recent purge,” said Hertog, the Saudi expert. “There are members of the elite who see risks, but they typically do not speak up.”

Prince Mohammed’s successes inside Saudi Arabia may hinge on his ability to bolster his leadership role beyond its borders. Just days after his purge of royals and the move to torpedo Lebanon’s government, he called for an emergency summit of the Arab League to send a message to Iran. Foreign ministers dutifully arrived in Cairo. Many of the Arab autocracies have been propped up by Saudi largesse, including Egypt, Morocco, Jordan, Sudan, and Djibouti, all of whom have signed on rhetorically to Riyadh’s crusade against Iran’s rulers.

He has pulled out all the stops in the effort against Iran, which has several times the population of Saudi Arabia and a rugged, fortresslike terrain. Prince Mohammed has reversed previously standoffish relations with Shia-dominated Baghdad to cultivate ties with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, and senior Shia clergy in the city of Najaf, attempting to decrease Iran’s influence.

Saudi royals also own many of the news outlets shaping opinion throughout the Arab world, including the Al Arabiya satellite news channel and the Asharq al-Awsat newspaper, owned by Prince Mohammed’s half-brother, Faisal, which toe the anti-Iran line. In recent comments to an American columnist, he likened Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei — the generally predictable 78-year-old cleric who has been either Iran’s president or the top official for the last 36 years — to Hitler.

“We know that the aim of the Iranian regime is to reach the focal point of Muslims [Mecca],” he said in an interview in May with Saudi-owned television channels. “We will not wait until the fight is inside Saudi Arabia and we will work so that the battle is on their side, inside Iran, not in Saudi Arabia.”

But to average citizens of the region, the power plays involving Iran, the Gulf States, Turkey, Russia, and the US and other regional actors have only complicated their lives, leading to chaos, war, displacement, and poverty in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq and raising fears of further conflict. Saudi popularity has been steadily declining, according to independent polling data. Another survey conducted last year shows that Arabs view the US and Israel as greater threats than Iran.

“Some, mostly Sunnis, do see MbS as a legitimate regional leader who represents their worldview and interests at this stage especially in regard to Iran’s regional rise and increasing adventurism,” said Ammar Abdulhamid, a Syrian-American blogger and activist. “Still, there’s a substantial segment that remains skeptical not simply in regard to his abilities but also to his intentions.”

Besides, he’s very young in a culture that still reveres the wisdom of the elderly. “MbS doesn’t seem to project enough gravitas at this stage to inspire a more positive popular outlook,” he said.

Regardless of Prince Mohammed’s ambitions and his support across the region, Saudi Arabia may be arriving too late in the game to win wider influence. Former and current diplomats say Saudi’s main aim is to roll back Iran without launching a direct war, and to win the support of the region’s Sunnis to do so.

But Saudi Arabia is competing against an Iran that has spent decades laying overt and covert security and intelligence infrastructure across the Middle East. Iran is already basking in declared victories on behalf of clients in Syria and Iraq, while Saudi Arabia remains mired in Yemen.

“Saudi Arabia lacks the networks on the ground and the military muscle to be as effective a player in various Middle East conflict theatres as Iran,” said Hertog, the scholar.

Those close to the Saudi leadership acknowledge they have been outmaneuvered by Tehran, but say Riyadh has begun the process of acting more decisively against Iran. “Clearly Saudi Arabia is late in aggressively responding to Iranian expansion and that explains maybe the abruptness of some steps but the new leadership has recognized that the old way of reacting,” said Shihabi. “Basically relying fully on Uncle Sam is no longer viable and it has to take matters into its own hands, hence the critical importance of Yemen.”

For now, many of Prince Mohammed’s mistakes and possible overreach are ignored because he’s seen as acting on behalf of his father, the 81-year-old king. But his brashness and any incaution could come back to haunt him once he’s on his own.

“He’s almost getting away with murder because he’s seen as acting on his father’s will,” said Rasheed. “When his father dies there’s going to be no one else to blame but him if something goes wrong.”

Munzer al-Awad contributed additional reporting to this story.