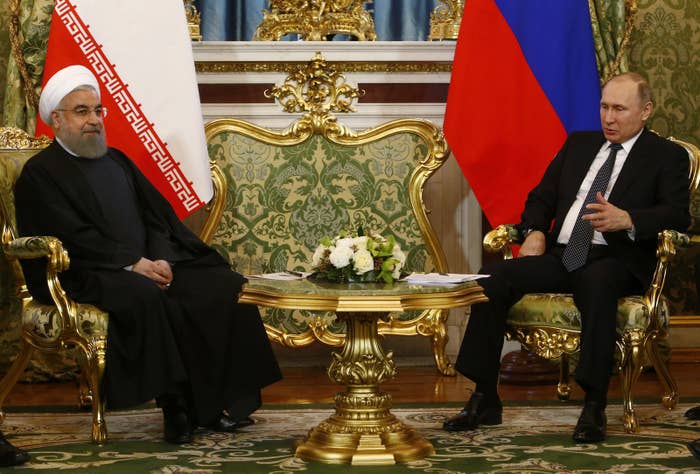

The white-turbaned cleric and the former KGB agent in a dark suit made for an odd pair. But when Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani visited Moscow to meet with Russian President Vladimir Putin in late March, the two men were keen to gloss over any differences.

Putin and Rouhani spoke about their joint fight against terrorism and expansion of the Bushehr nuclear power plant in Iran, built with Russia’s help. Putin heralded that trade between the two nations had grown 70% in the last year. They announced plans to build a thermal power plant in southern Iran and launch a railway project in the north, and the easing of visa rules. The night before, Tehran had quietly given Russia permission to use Iran to launch military flights to Syria, where both nations back the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

“Russia and Iran are on the threshold of unprecedented rapprochement,” Russian state TV declared, “and are opening a new page in the history of their relations.”

Contrast that with the visit of US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who arrived in Moscow on Tuesday. The Kremlin pointedly declared that Putin had no plans to meet with Tillerson, in an intentional snub that broke with how Moscow typically treats America’s top diplomat. Tillerson’s predecessor, John Kerry, met frequently with Putin on his trips to Moscow.

“If he doesn’t get a meeting with Putin, he’s just delivering talking points,” said Evelyn Farkas, a former senior Pentagon official handling Russia during the Obama administration.

Tillerson hopes to get the Kremlin to distance itself from Iran, and to rein in Assad after his regime’s alleged chemical weapons attack last month, which triggered US airstrikes. Ahead of his trip to Russia — which had been scheduled well before the airstrikes — Tillerson said Russia had to choose between the US and Iran.

“Russia has really aligned itself with the Assad regime, the Iranians, and Hezbollah,” he said. “Is that a long-term alliance that serves Russia’s interest, or would Russia prefer to realign with the United States, with other Western countries and Middle East countries who are seeking to resolve the Syrian crisis?”

But Tillerson may be in for a rude awakening.

“The one thing we’ve seen repeatedly over the last years, is Russia is not willing to back down,” said Andrey Baklitskiy, a Middle East expert at the PIR Center, a Moscow think tank. “It’s learned you get more if you act like a tough guy than if you just compromise and give in. During the last four years Russia pretty much did what it wanted and didn’t change course for a minute even. From the point of view of Russians, it was done in the right way, so why change that calculus?”

US policymakers have for years wondered aloud about the prospect of convincing Russia to ditch Iran. The Trump administration has made similar noises. But White House officials have also articulated and carried out contradictory policies on Russia and Syria, though they have consistently said they sought to oppose Iran’s ambitions.

Experts and former officials say Russia would likely demand an exorbitantly high price to jettison relations with Iran and their Syrian client. Moscow has spent decades building and cultivating intelligence and security ties with Tehran, which it won’t easily give up. Iran and Syria’s anti-American propaganda plays well into Russia’s strategic goals. The Syrian regime provides Moscow a way to maintain influence in the Middle East, and a front to stand up against the idea of Western-driven regime change, as well a warm-water port it has coveted for centuries. Iran, meanwhile, provides Russia with a market for energy deals, industrial goods, and potentially its weapons, once sanctions are removed in three years as part of the landmark 2015 nuclear deal negotiated by the Obama administration. And on the global diplomatic stage, Moscow provides Tehran with a defender at the UN Security Council.

“Asking Russia to dump its strategic interests in Syria and Iran is unrealistic,” said Farkas, who is now a fellow at the Atlantic Council. “They’re not going to walk away from [Assad] unless we’re willing to give them something big.”

Despite their current alliance, Russia and Iran have historically been rivals, even enemies. Over the centuries, they have fought wars and squabbled over spheres of influence. Stalin occupied northern Iran after World War II, a memory that continues to haunt Iranians, who chanted “death to the Soviet Union” along with the US and Israel in the 1979 revolution that ousted Iran’s pro-US monarch. But all that changed under Putin, who has courted Iran and other players in the Middle East since 2000. Russia–Iran cooperation took on a whole new dimension during the Syria war, where Iranian, Russian, and allied forces have sometimes fought side-by-side against clients of US allies such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

“We tend to look at the history of these two countries — a history of rivalry and distrust,” said Anna Borshchevskaya, a Russia expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “But given the current context they’re only moving closer. It’s really unprecedented in the grand scope of the last 500 years. They’ve been able to put their differences aside, at least for now.”

Moscow is not averse to dangling the prospect of distancing itself from Iran. The Kremlin whispers the possibility to the US, Western diplomats, and Iran’s Arab enemies in the hope of gaining concessions and softening policies, such as the sanctions placed on Russia after its invasion and dismemberment of Ukraine. In short, Moscow itself sometimes plays the “splitting with Iran” card to manipulate world leaders at their wits’ end over what to do about an increasingly powerful Iran.

This was on display 15 years ago, when Putin got George W. Bush to sign an arms deal only to quickly turn around and renege on an agreement to distance Russia from Iran. Moscow agreed to sanctions on Iran over its nuclear program in 2010, but only after the Obama administration lifted sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Georgia. Later Russia worked hard to dilute sanctions on Iran so they wouldn’t interfere with its own business interests.

“I think Russia got the better deal,” said Borshchevskaya. “It got exactly what it wanted.”

Still, Putin’s grim Hobbesian worldview likely precludes any permanent allies, and Russia and Iran have significant differences over how they’d like to see the Middle East. Moscow prefers secular, military strongmen like Assad and Egypt’s Abdel Fattah al-Sisi — whom Trump also supports — while Iran seeks to empower ideologically motivated Islamist populists like Iraqi cleric Moqtada Sadr or Lebanon’s Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Despite signs of strains, they’ve so far papered over any differences and accommodated each other.

By sticking by Iran and Syria, Putin also shows the world Russia is a more loyal ally than the US, which shocked many of its regional partners when it called on Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak to step down in the early days of the so-called Arab Spring. Offering Russia an incentive here and there won’t be enough to induce a betrayal.

“Lifting sanctions and imposing sanctions is something that can be done and undone,” said Baklitskiy. “But walking back from your ally does you a lot of damage that lasts for a long time. What Russia got from supporting Assad, despite everything that happened, gave it a lot. When Trump said we might support NATO, we might not, that did a lot of damage to the US. And that’s something that’s not really quantifiable.”

To win over Russia, the US would have to transform its foreign policy and military posture, especially with regard to NATO’s eastward expansion, which Russia angrily opposes. “The Russians want to build up their power so they become a global power to put a check on us,” said Farkas, who is now a fellow at the Atlantic Council.

“The US wants to impose its values, vision, and rules on the entire world,” said Alexey Khlebnikov, a Middle East expert at Russian International Affairs Council. “The US would have to take into account Russian interests, and not to push a US-led agenda like it’s the only right and only possible way. It would require the US to reconsider its entire approach to Russia.”

John Hudson contributed reporting from Washington