Yasaman was too young to join her siblings and parents as they took part in the 2009 unrest that last threatened to disrupt the regime in Iran. Now they’re aghast at her participation in the protests that are currently rattling the country. But that disapproval didn’t stop the 21-year-old as she surveyed the scene in front of the gates of Tehran University on Tuesday afternoon, the sixth day of the demonstrations.

It’s easy to understand why Iranians would oppose their 37-year-old clerical regime, a religious autocracy characterized by corruption, mismanagement, and political and social repression. Lately that list of grievances has included risky and expensive adventures abroad. The Trump administration and some Iranians in the diaspora have wholeheartedly embraced a week of anti-government protests that mostly began in small towns and cities and have since spread across the entire country.

But for Iranians inside the country, joining a nebulous, leaderless protest movement involves extraordinary physical and political risks. Older Iranians say they went to the streets in a 1978–1979 revolution against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, only to get a regime they despise more.

Many of those who took to the streets in the 2009 “Green” uprising against the disputed reelection of then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad are sitting these protests out. In 2009, the protests were led by the middle-class youth and professionals alongside the country’s reformist political faction, once an integral part of the ruling elite. But poor and lower-middle class families in Iran’s flyover country — small towns on the country’s periphery, agricultural hubs, and dreary satellite towns of large cities — appear to be at the forefront of today’s protests.

Yasaman’s family is among those who’ve stayed indoors as others have gathered to march, she later told BuzzFeed News in an interview conducted over WhatsApp. (She asked that her last name be withheld for fear of reprisals.) Her friends derided the protesters as “tribal” small-town folks; they’re burning police stations and attacking security forces, they said, not out of political considerations but to settle rural vendettas, reflecting part of the bigotry of the cosmopolitan elites toward the rural poor that has characterized Iranian society for decades.

“People in Tehran are not as hard-hit by the issues, which are driving protests in the periphery,” said Mohammad Ali Shabani, an Iran scholar at the School for Oriental and African Studies in London. “They have more access to services, jobs, though Tehranis are by no means spared from any of the ills of the current state of the economy.”

He added, “The current protests appear to show the middle class largely staying at home at least partly for fear of the violence perpetrated by the working class.”

Middle-class and urban participation is a decisive factor in whether the protests will lead to significant change or can be stamped out by Iran’s security forces. “For any successful protest movement of this type with radical demands a broad alliance is required,” said Mohammad Ali Kadivar, an Iran expert at the Watson Institute at Brown University. His research suggests the protests might be winding down, although they could be given a boost on Friday.

“They need the numbers,” he said. “Tehran is crucial because it’s a city of millions. If the protests stay within these small towns I’m not sure how long this can persist. Protesters can also get tired, and do get tired.”

The origins of the protests have also confused many Iranians, contributing to the disorientation confronting anyone trying to understand Iran’s political alliances and undercurrents. The marches were originally spurred by hardliners in the religiously conservative city of Mashhad, perhaps to embarrass the moderate president Hassan Rouhani. The president had earned their anger after revealing previously undisclosed details about budget allocations to the senior clergy’s pet projects in the weeks before the protests began.

Though the movement may have since taken on a life of its own, many among those sitting on the fence have suspicions that it is being allowed to fester in part to put pressure on Rouhani, who was elected twice thanks in part to the support of the 2009 movement’s backers. “The middle class in Iran are educated and experienced enough to understand who is who in this theater,” said the editor of a centrist Tehran newspaper close to the leadership. He spoke to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity, given the chance of a potential crackdown. “On the other hand they know that no government better than the Rouhani’s one is waiting for them, so they are very cautious and even critique unrest, which quickly falls into the hands of inexperienced teenagers or mobs.”

On Wednesday, the commander of the Revolutionary Guard, Maj. Gen. Mohammad Ali Jafari, strongly suggested that Ahmadinejad, a onetime darling of the hardliners who now rails against the establishment, could have been behind the protests. The centrist newspaper editor noted that preventing Ahmadinejad and his ilk from coming to power was the entire reason they took to the streets.

“I was active the whole of 2009 and I went into the streets and we got beaten,” said Ali, a 26-year-old unemployed architect in the northern city of Rasht, a major industrial hub of 650,000 that has been the scene of nightly demonstrations. “We are more than anything in shock. How did the protests become so serious all of a sudden? The longer this goes on, the more it hurts Rouhani. There’s a large possibility they want to bring him down because of his stance against corruption.”

Iran’s demographics are changing as well, shifting the makeup of the people taking to the streets. Ninety percent of those arrested appear to be under 25 years old, according to Iranian officials, but Iran’s youth bulge has flattened; Iranians are aging and perhaps less willing to take risks. They stood in long lines in 2013 and 2017 to elect Rouhani, who has at least tried to bring a measure of accountability and moderation to Iran’s domestic politics.

“Thus, beyond class, there appears to be a generational gap between those on the streets now and those who went out into the streets in 2009,” said Shabani.

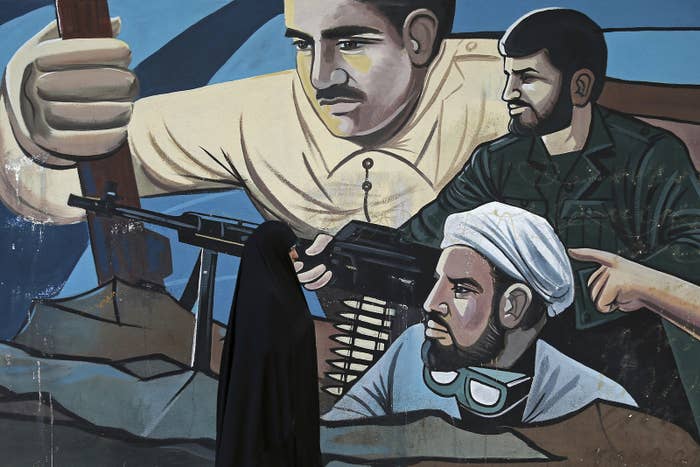

Iranians know regime change will be expensive and bloody. Not only does the Islamic republic have multiple tools of violence and coercion available, it’s shown a willingness to use them. The regime is also adept at mobilizing loyalists: On Wednesday, the regime organized pro-government rallies throughout the country, trotting out die-hard supporters as well as others compelled to join in for the sake of their careers or educations.

Confronting Iran’s security forces can be terrifying. In addition to riot police, unaccountable groups of armed thugs loyal to shadowy religious associations rather than the government patrol the streets. On Tuesday at around 6 p.m. in Tehran, just as it went dark, Yasaman said she suddenly saw a gang of heavyset, bearded enforcers armed with stun guns, chanting slogans in praise of the Shia saints and the supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, who has called the protests a tool of Iran’s foreign enemies.

At the protest on Tuesday, without warning, the riot police began to pounce on the young people. She and her friend ducked into an alleyway, pretended to be smoking cigarettes when a regime thug spotted them. He was bearded, heavy and angry, but he let them off with a warning, ordering them to move on.

“Death to the dictator!” the protesters chanted, as they ran down past the shuttered bookstores of Enghelab Street to avoid an arrest, which could mean a few hours in a holding cell or years-long prison term that may include solitary confinement. Someone — either a demonstrator or a provocateur — hurled a rock at a police officer. That’s when the tear-gas rounds began to go off, the fumes burning her eyes and making her cough. A riot police officer pounced, beating Yasaman and her friend with a club.

“My family is so worried about me,” she said, as she nursed her bruises after a day in the streets. “They oppose my presence on the streets for a rally, but when I insisted, they do not say anything, just, ‘take care.’”

Yasaman said she had no specific reason to go into the street, but every reason to be there. “Today all people have problems with everything,” she said. “I hate this system and I want it to change. I want to be active. I do not want to be indifferent. I regret voting for Rouhani.”

Her anger spills out in a jumble. “I’m protesting everything,” she said. “I’m protesting the headscarf, the polluted air, poverty, nervousness over earthquakes. Why should Iranian people be introduced as the meanest people in the world? The authorities think we are ignorant. We are not respected in the world. No one is held accountable.”