ISTANBUL — Already mired in conflict, the Middle East woke up on Wednesday to a disturbing new reality. The US had elected a man who has vowed to drastically change American policy in the region, and made outrageous statements about the region’s majority Muslims — but whose ultimate intentions and beliefs are so scattered they remain largely a mystery.

“The region is a mess,” a UK diplomat said on condition of anonymity. “Does it need somebody to shake it up? Maybe. But I don’t know who these Trump people are and what they are going to do.”

Unlike Barack Obama, who was a product of the mainstream of the Democratic Party, Trump is a “one-man show” who may completely renege on all the promises he made during the campaign, said Behlul Ozkan, an Istanbul professor of international relations. “What he says and what he’s going to do might change dramatically,” he said.

Policymakers, diplomats, and analysts in the Middle East are worried, often terrified, about what Trump’s victory would mean for a region already in flames. One United Arab Emirates newspaper, Ittihad, called Trump’s win a “political earthquake.” Authoritarian rulers were heartened, while democracy advocates were dismayed.

“Trump is going to get along with every autocrat in the Middle East,” said Emile Hokayem, of the Institute for International Security Studies in London. “He’s not interested in regional security architecture. He’s not interested in setting down norms. He’s not interested in winding down conflicts in ways that are just.”

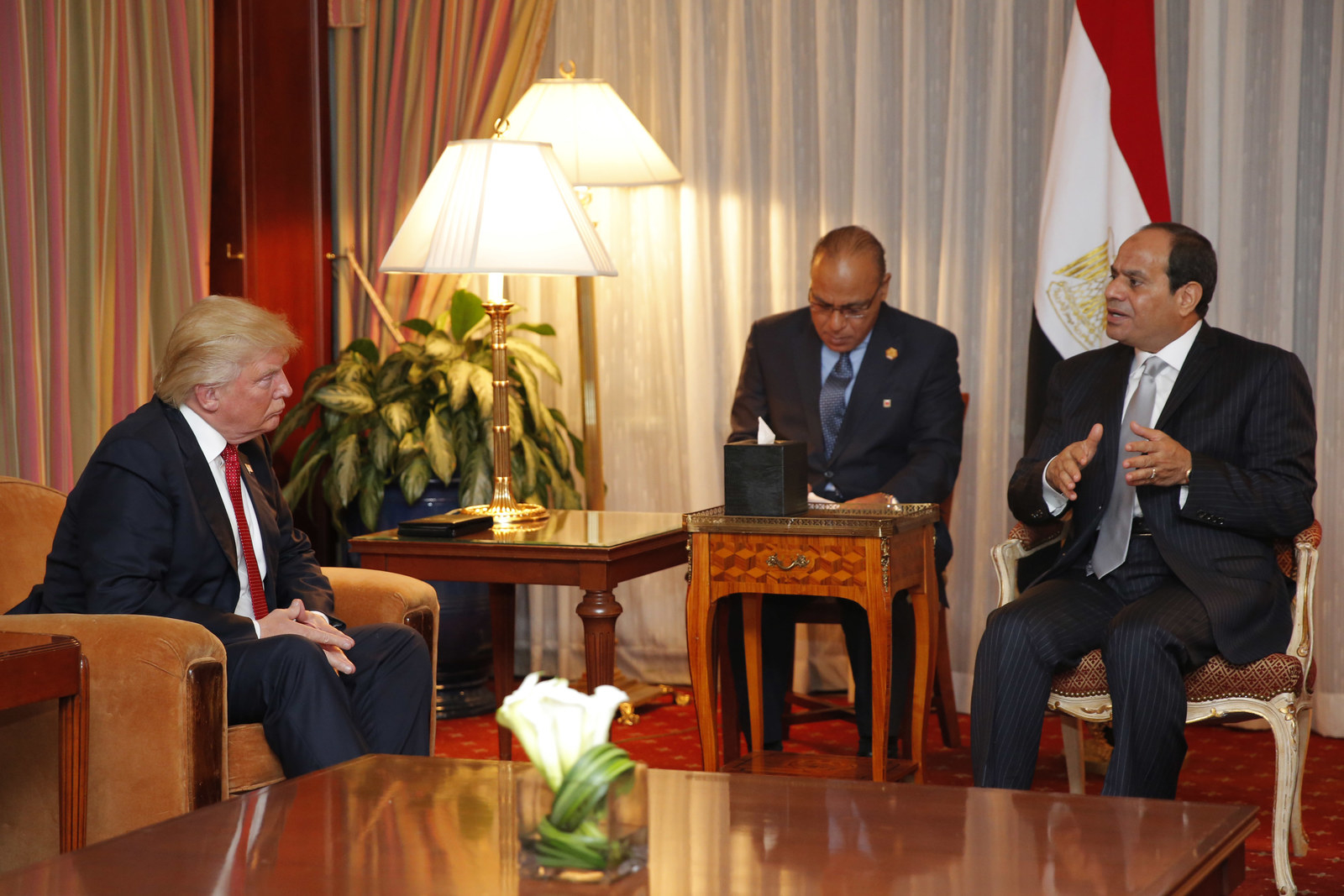

Over the course of his campaign, Trump vowed to drastically change the way the US operates in the Middle East. He said he would scrap the Iranian nuclear deal, withdraw any support for Syrian rebels fighting Bashar al-Assad, and change the way the Obama administration has been pursuing the war against ISIS. He also hinted that he would cosy up to regional strongmen such as Egypt’s Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who claimed to be the first world leader to congratulate him, and populist leaders such as Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan — regardless of concerns about human rights.

Trump has never been in government, and thus has no foreign policy track record to scrutinize. He has made contradictory statements about how he would address the Middle East’s troubles, and many analysts have dismissed some of his most provocative statements as campaign bluster. And while he has surrounded himself with some leading Republican Party foreign policy hands, he has also rejected George W. Bush’s Iraq war as a mistake and argued against the GOP’s foreign-policy elite. Amid this confusion over what his goals are, many in the region anticipated no substantive changes under a Trump presidency. “Wars in Iraq, Syria, Libya continued regardless of who was in charge,” an analyst on the pro-Iranian al-Mayadeen TV said. “I have not noticed any change to allow us to say now that Republican policy will be worse or better for the Middle East.”

Whether Trump will attempt to change course in the Middle East or not, the often grim realities of facts on the ground in the region, limits on US power in an increasingly multi-polar world, and Washington’s declining political and economic influence will likely temper any drastic shifts. Still, diplomats and analysts across the region expect some changes, and in interviews sketched out how a Trump presidency might affect the Middle East.

Syria’s civil war

Up until now, the US has given tacit support to the Syrian rebels fighting Bashar al-Assad, or at least okayed the dispatching of weapons and paying of salaries to the fighters by Saudi Arabia and Turkey. But Trump has said that, while he has no love lost for Assad, backing the rebels was a mistake, and that the US would be better off supporting Damascus’s ruler as a hedge against Islamic radicalism. If a Trump administration were to use its influence to throttle the rebellion or pull the plug on the Syrian opposition abroad instead of supporting it, it could dramatically change the balance of power in Syria in favor of Assad and help him wipe out the armed uprising against his rule. “Trump is not interested in the Syria fight,” said Hokayem. “It doesn’t seem like he wants to use Syria as a battlefield against Iran. He doesn’t see a moral obligation in Syria.”

On the other hand, there may be limits to what a Trump administration can do. Turkey and Saudi Arabia appear deeply committed to supporting the Syrian uprising and could decide to pursue the battle regardless of what Trump wants. Corner the rebels too much, and their Saudi and Turkish patrons may ignore longstanding US requests not to hand fighters the portable surface-to-air missiles they want to down Russian and Syrian warplanes.

The Iran deal

Trump has called the Iranian deal, which puts limits on Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief, a disaster, vowing to “rip it up.” It is unclear whether he would try to renegotiate it, or to resume maximum pressure on Tehran to halt the enrichment of uranium. But the complete scrapping of a deal enshrined into international law by the UN Security Council might be tough, especially if it means that Iran could start ramping up its uranium enrichment and other elements of the deal. Technically the Iran deal remains in the hands of the UN and its enforcement agencies. European companies have already begun cutting major deals with Iran, and may choose to ignore the Trump administration. “I think we would be very resistant to being told we can’t do business in Iran,” said a Western diplomat in the Middle East on condition of anonymity. “We would say go back to the Security Council, and they won’t get the resolution.”

A Trump administration may argue to opponents of the Iran deal that key provisions of the agreement lie out of its hands. The nuclear deal “cannot be overturned by a single government,” Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani was quoted as saying by state television after Trump’s victory.

But after facing off with an Obama administration that was inarguably the friendliest to Tehran in decades, Iran could have much to lose under a Trump presidency. Even if Trump can’t scuttle the nuclear deal, he could behave in such a confrontational way as to give Iranian hardliners the pretext to abandon it. The US military and economy still carry considerable weight in the Middle East. “If a US president takes a confrontational stance toward any country in the Middle East, that situation will deteriorate,” said Marc Chehab, director of the peace and security program at Foraus, a Swiss international policy think tank.

Israeli officials, meanwhile, said they would move quickly to push Trump to take a hard line against Iran. "It is not realistic to think he will 'rip up the deal' as he has said in his speeches, but there is a lot he can do outside of that to make it clear that the US is not a friend to Iran. He can take a much tougher line with Iran. We are keen to see that happen," said an Israeli official in the Foreign Ministry, who spoke on condition of anonymity. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu “sees an opening for a tougher Iran stance under a Trump presidency.”

The war against ISIS

Trump has criticized the ongoing US war against ISIS in northern Iraq and Syria, arguing variously that it was not employing enough firepower or that Washington mistakenly keeps alerting jihadis to upcoming operations, including the ongoing offensive on Mosul. But he has rarely spelled out what he would do differently. And once confronted with the complicated jigsaw puzzle of conflicting sectarian, ethnic, and national interests that make up the US-led anti-ISIS coalition, he may decide that it would be too difficult to unravel. “The war against ISIS is an ongoing operation,” said Hokayem. “By the time Trump comes to the White House, there will be even more progress and he may not want to touch it.”

Hoshyar Zebari, Iraq’s former foreign minister, said it might be well into next year by the time any Trump administration begins to consider changing tactics on ISIS. “The US has its own assets and own advisers and air support in the fight,” he said. “This commitment will continue irrespective of the administration. I don’t believe much will change, judging by the investment the US has put in this battle. You cannot just switch it off and put it away.”

The greater worry is that combating militant extremists could become the sole prism through which a Trump administration views the Middle East, said analysts.

“The danger is the fight against ISIS will become the lynchpin of US policy,” said Hokayem. “That means: We need to fight against ISIS so we need to cooperate with Russia or Assad or whomever.”

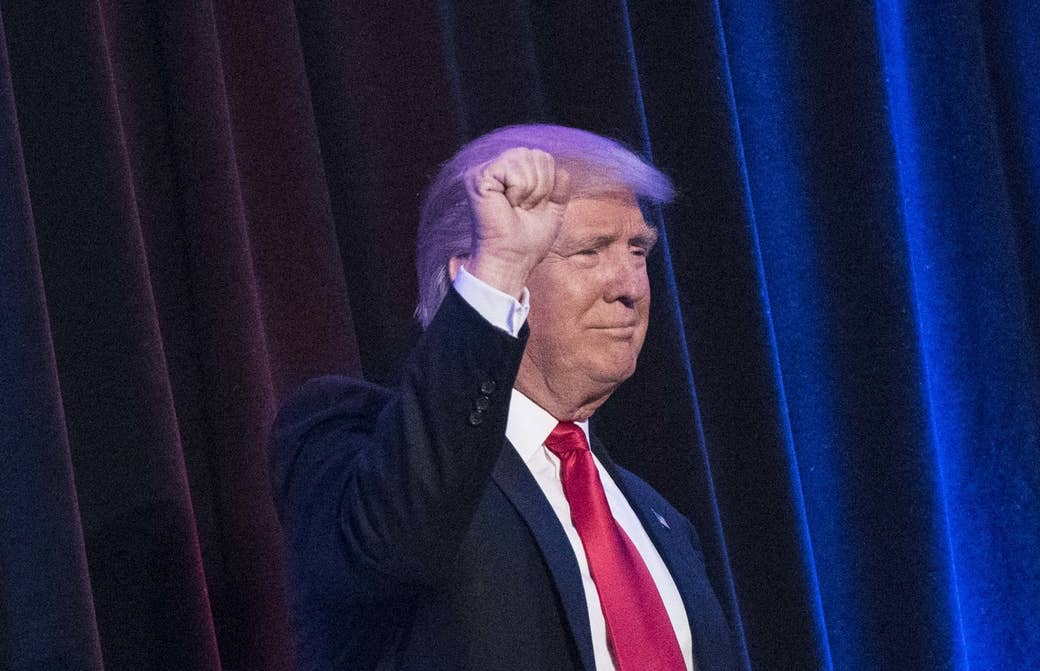

Cozying up to autocrats

Egypt’s Sisi was among the very first world leaders to congratulate Trump on his win. The two men met in New York in September and afterwards Trump called Sisi “a fantastic guy.” Throughout the campaign he has advocated the use of torture, and now Arab liberals and democrats worry that the US will care even less about issues such as human rights and corruption in the region. “We would like to have US support for political process that was designed and led by the Americans,” said Shirouk al-Bayachi, a liberal member of Iraq’s parliament. “Actually we are not sure at all what he will do, and it’s crucial for Iraq to have an American role.”

But Trump has already expressed reluctance to criticize autocratic governments in the Middle East. He praised and defended Recep Tayyip Erdogan after the Turkish president arrested and fired tens of thousands of Turks following the failed July 15 coup attempt. “I think it’s very hard for us to get involved in other countries when we don’t know what we are doing and we can’t see straight in our own country,” he told the New York Times in July when asked about the crackdown.

In the waning years of the Obama administration, the White House did little but issue press releases whenever a Middle East autocrat jailed a journalist or opposition politician. But some say that at least provided a small measure of hope for the region’s embattled democracy advocates. “Suddenly the US is going to not care about human rights and domestic politics,” said Hokayem. “Now it’s going to drop the human rights pretensions.”

Trump’s victory will likely embolden the region’s populists and demagogues, reinforcing their belief that they are on the right side of history.

“The followers of Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party would like to play up the idea that liberal Hollywood opinion-makers failed,” said Yusel Taksin, a political science professor at Istanbul’s Marmara University. “They would like to use Trump’s victory as an example of the silenced people speaking out.”

Israel

During the Republican Party primaries, Trump argued he would be a more even-handed umpire in the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians than previous US presidents. But despite garnering the support of known anti-Semites and evidence emerging that he or his campaign were visiting anti-Semitic websites, he managed to win the implicit support of Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Trump and his surrogates have argued for Israeli annexation of the West Bank and recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, policies that would favor Israel far more than even past Republican administrations.

With the presidency and majorities in Congress, Trump could easily push through such radical policy changes. Yet some wonder whether he would. For one thing, he and his advisers’ positions on Israel have been all over the map. For another, making such moves might be too costly. George W. Bush signed a bill recognizing Jerusalem as capital of Israel, but held off on implementing for fear it would create more problems than it would solve.

“It will anger all the Arab states,” said a Karel Valansi, a writer for the Turkish Jewish newspaper Salom and P24, an Israeli news website. “Now the Arab–Israeli conflict is dormant. Making big changes might mean the fragile relationship between Saudi Arabia and Israel will break down, and there will be another wave of problems in the area.”

A senior Israeli official in the prime minister's office said there was no expectation that a Trump White House would try to push a peace deal between Israel and the Palestinians. "Through channels close to Trump, Netanyahu has understood that this White House will be friendly towards Israeli policy. There will not be the same condemnation towards the [West Bank] settlements that we saw under Obama, and before him Bush," said the official, who added that Sheldon Adelson, the American casino mogul and billionaire backer of Trump, had directly communicated with Netanyahu to assure him over what a Trump White House would look like. "We are being told this will be a very friendly White House to Israel."

But other Israelis sensed a new era. On Wednesday morning, Naftali Bennett, the minister of education, said in a press release: “Trump’s victory is an opportunity for Israel to immediately retract the notion of a Palestinian state in the centre of the country, which would hurt our security and just cause.

“This is the position of the president-elect, as written in his platform, and it should be our policy, plain and simple. The era of a Palestinian state is over.”

New ideas?

Despite worries over how the Trump administration might handle a Middle East riven by strife, the Obama administration hasn’t been doing so well either. In numerous countries it has pursued policies that do not seem to be working at all, apparently unable to change course. One UK diplomat in the Middle East said the Americans were leading allies in pursuing paths that seemed be heading nowhere in Libya, Syria, Yemen, and Sudan. Perhaps a Trump administration could lead the international community back to new ideas and plans.

“A whole series of situations that the Americans had got themselves into, which weren’t going anywhere, are potentially up for grabs,” said the diplomat. “If you’re coming in as a new administration and you don’t want to just pursue old policies and are saying all their policies were crap, it does give an opportunity to do something different. It’s not such a bad idea to go back to the drawing board, is it?”

On the other hand, Trump’s penchant for unpredictability and refusal to abide by diplomatic or social niceties — traits that served him well in the primaries — may be enormously destabilizing to a region rocked by numerous wars and humanitarian crises.

“He is notorious for playing up his ignorance and unpredictability in foreign policy as an asset,” said Chehab. “But in diplomacy, that’s not an asset. You should really have a good plan. His attitude is a major risk for the Middle East and the world order in general.”

Additional reporting by Sheera Frenkel.

Correction: Sheldon Adelson was previously described as an Australian. He is American.