On 16 June Jo Cox, a British MP, was shot in Birstall, near Leeds, in northern England. She died from her injuries on the same day. The suspected gunman, Thomas Mair, who reportedly was a longtime supporter of a U.S.-based neo-Nazi group the National Alliance, is in custody. If her death ends up being treated as a political assassination, it will be an event we are unused to in the UK (the last sitting MP who was killed was Ian Gow, in 1990).

For maybe the dozenth time in a few days, when I heard the awful news, I burst into tears. Cox, 41, was a mother to two very young children, married to their father, and a beloved friend to many; her loss is a terrible blow to her loved ones, a shocking and unexpected event, the sort of thing that simply shouldn’t happen. In the wider world, Cox was previously an activist and campaigner, and, as of 2015, a politician – a first-time Labour MP who stood up in parliament this past April and asked the government to accept 3,000 child refugees from Syria. Her death extends beyond those who knew (and loved) her personally.

I am far from my London home, where we will soon be voting to either remain in the European Union or leave it – a “Brexit”, as we have clunkily portmanteaued it. The dialogue, even from this far away, has been a toxic soup, all of us choking it down and spluttering, but mulishly not leaving the table. It’s not even a new dialogue – Great Britain, formerly a colonial empire that stretched across the globe, has been oddly defensive about letting anyone else in for a long time. I live in America now, where another toxic conversation has been underway for a long time as well, currently spearheaded by the presumptive presidential nominee of the Republican party, Donald Trump. The man who tweeted “AMERICA FIRST!” earlier this month has come up with some of the most repugnant rhetoric around pretty much every group of people over the last several years, with particular destructive vitriol reserved for Muslims, foreigners (and the children of foreigners), and women.

I am all three of those things, and I am tired.

The mental energy required to live with the bombardment of his opinions, and the implicitly sanctioned opinions of his increasingly boorish acolytes, grows ever greater. It has an almost tangible weight, like a cloak – or more honestly and uncomfortably, two large rocks, tethered to a stick across my shoulders – and it follows me around, invading every cranny of personal space. It crowds out my brain and steals my emotional bandwidth, broadcasting on a frequency it has no permission to access.

This is the month of Ramadan, the one month most non-Muslims know the name of, as well as its attendant obligation for Muslims: to fast, from dawn to dusk, in an act of self-denial, meditation, and piety. It’s a tiring month, one that has always been marked for me, by fatigue, in addition to all of its more esoteric spiritual rewards. It’s a fatigue many of us push through because we have other responsibilities, work and family chief among them, to attend to, and like “good minorities”, we are always wary of being made to look as though we are seeking “special treatment”. The month is about so much more than abstaining from food and drink; it is about being a better person, a better Muslim, turning away from the worst, most base elements in our being and becoming the best version of ourselves. I swear less during Ramadan. I fix my mouth to not gossip so damn much. I give more to charity and try to be more charitable in my interactions with others. It is a battle – on a religious level, but also in the broader context of living in the world, subject to its many demands and temptations. We are all fallible.

My reading of these stories are laced with a sorrow that is rooted in fear – that could have been me.

I have been working as a journalist for most of my adult life, and working out of newsrooms means a far more sensitive ear. The news is something we report and reflect on, but our exposure to it manifests as more than just work. We are conduits of the news, but the news also lives in our skin, lingering long after we have sent copy off to our editors. In consuming and contextualising the news, that same skin can be pulled taut on a number of stories, the ones that “speak” to us on a different level. Stories of rape and domestic violence are never “just” sad news items, for example, but a reminder that these issues are existential threats for people like me. The drowning of black and brown bodies in the Mediterranean, a story that has occurred so many times but whose horror is never lost, makes me look at my own name and reflect on the choices my parents made in emigrating to the UK long before I was born. My reading of these stories is laced with a sorrow that is rooted in fear – that could have been me. And alongside this thought, I go about living my life, doing my job, and trying to be kind and understanding.

I arrived in New York on the same day as the first Super Tuesday of 2016. Back then, the Republican race had more horses in play: Rubio, Cruz, Kasich, and, of course, Trump. I turned on my faithful wireless radio and found WNYC and NPR (it has become the soundtrack to my morning ablutions) and was immediately caught in the sharp undertow of American politics. Ridiculous soundbites, such as equating the size of a man’s hands to the size of his penis, for example, became a thing that swirled in the political news cycle for far too long. The implicit – those feelings many of us with hyphenated identities have been aware of in a vague but real way – became explicit. Foreigners and their offspring should go back to where they came from; an entire religion was relegated to the scrapheap of terror, good only for incubating horror; women became a collection of walking, bleeding orifices… No opinion seemed too repugnant to air. It’s all out in the open. And so swaths of America – not all, no, but a good enough number to jar those of us who feel it the most – Leaned In and began to really go for it publicly.

If you don’t know, living like this is terrifying.

Donald Trump and the rhetoric he peddles so easily represents a huge leap forward (or backward, depending on how you see this) in the movement to ensure that I – a female Muslim of Nigerian descent – do not exist in the American landscape. Every day, I come into the office, and I am told, over, and over, and over again that people like me are unwanted. The exposure to it feels like a Silkwood shower in reverse: I come in, tear away the protective shell I have built and step into the fray, misting myself with the sludge of hate directed at me and mine. During the month of Ramadan, when my mental defences are a little less solid, the deluge feels insurmountable. I am an untested boxer, stepping into the ring with the world champion.

A Muslim journalist friend, tasked with listening to and writing up Trump’s speech following the massacre at a gay club in Orlando, told me she walked away from her desk and took a restorative shot of tequila afterwards to fortify herself. I have implicit and explicit pacts with friends to not link to Trump’s many fuckeries unless it’s for work. You best protect ya neck, RZA told us. Wu-Tang is for the children, and also for us.

To be “sitting this election out” reeks of a repugnant sort of privilege.

I realise that my assured immigration status is relatively cushy as compared with so many others’ – I am on a visa (from the United Kingdom, of all places!); there is no language barrier for me to overcome, and I am in paid employment. I am Other, and the worlds I know most intimately are becoming increasingly uncomfortable, but I still have the luxury of the option of packing my bags and returning to the also-troubled land from whence I came (London, for the obtuse). I think about that option when I see Americans say that they are not going to vote, either in protest at what they call a rigged process, or more worryingly, because Trump is “what we deserve”, a slap in the face to shock America into a corrective overhaul of its cultures and systems.

Here’s what I think: His usefulness as the most “necessary” jolt back to common sense is severely limited and/or massively overrated. To be “sitting this election out” reeks of a repugnant sort of privilege. The damage that life under would-be President Trump would introduce does not lie in the not-too-distant Future; it is in the Right Now, under Presumptive Presidential Candidate Trump.

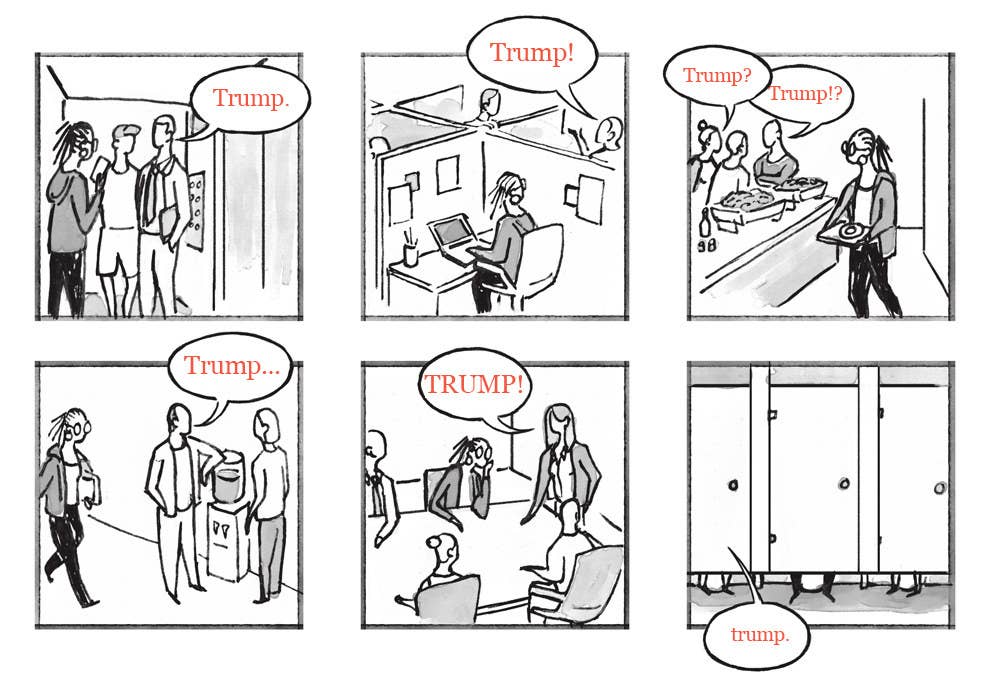

It is the noxious idea of a fictitious Great American past, which allows citizens to incite hatred and fear, and stoke it to such a tempo that it leaves those most at risk in a state of constant terror. It is in the weary sighs of people who know that the worst of this election cycle is still to come. The damage flutters in the chests of people whose hearts race when they hear a combination of hated keywords – words such as “Trump”, “speech”, “rally”, “wall”, “women”, and “Islam” (a not-exhaustive list). The damage lives in the tension headache of listening to or reading a transcription of a speech that unleashes a stream of invective; speeches that grow more worrisome in their tone and frequency. The damage chips away at the self, burrows in and makes itself at home, erodes defences like water does topsoil. The damage strips away at the soul, leaving the body diminished over time.

The damage being done is having effects in the here and now.