In the 1,000-plus days since Flint, Michigan, had (federally acceptable) potable water, a lot more than the pipes has eroded.

Trust, like dependably clean water, is not easy to come by in this slightly careworn city of just under 100,000 people. For residents, the knowledge that a toxic cocktail of contaminants had been inadvertently released into their water supply is bad enough. But the water crisis is also understood as part of a grander historical narrative of neglect and political dismissal.

For a city that has given the US — and by extension, the world — so much (the modern automobile industry as we know it was Flint-bred), Flint has been treated shabbily indeed. And beneath the patina of low-level anger at the great injustice it has been — and are still — experiencing lies another layer, familiar to other victims of municipal wrongdoing the world over: weary resignation. As I talked to residents of Flint, or “Flintstones” as some call themselves, over several days in February (during which time the state released its Civil Rights Commission report, which highlighted systemic and historical racism as one of the root causes of the crisis), there was a palpable skepticism that things would get better anytime soon. That’s because what we know to be unacceptable has long been acceptable in Flint. If you were to set a timer on how long it takes for “outraged” to become “stoical,” it’s somewhere in the region of two and a half years.

The story of how Flint’s water supply came to be dangerous for consumption is largely familiar at this point, but here’s an encapsulation: On 25 April 2014, the city of Flint switched to the Flint River as its new water source. (It had previously drawn from Lake Huron.) Residents began complaining about skin rashes and the smell and colour of the water soon after. In response, the city issued “boil water” advisories in August and September 2014, and increased flushing of the water mains. By October, General Motors had switched its supply source to Flint Township over fears that the chloride in the treated water from the Flint River was causing corrosion in its machines. In early February 2015, Flint resident LeeAnne Walters complained about rashes on her son’s body, and by the end of the month had reached out to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In August 2015, a researcher from Virginia Tech named Marc Edwards began testing Flint’s water quality; in September, he alerted the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) that the water’s corrosiveness was causing the pipes to leach lead. (The DEQ disputed the results of Edwards’ study.) Later that month, Dr Mona Hanna-Attisha, a researcher at the city’s Hurley Medical Center, found high levels of lead in Flint’s children, prompting officials to issue a lead advisory — and to reiterate that the city’s water complied with federal safety laws.

On 1 October 2015, 524 days after the switch to the Flint River, the Genesee County Health Department declared a public health emergency and urged Flint residents to refrain from drinking the water.

The water crisis is part of a grander historical narrative of neglect and political dismissal.

By the time I left Flint on 22 February this year, the water was still not safe enough to drink directly out of the faucet, according to the politicians and charity workers I spoke to, and the residents’ feelings on the matter had remained at a simmer about it, quelled only slightly by whole-house filters and bottled water (either privately purchased or received gratis from the city). The flip-flopping of city and state officials over the water crisis confirmed for residents something they had quietly considered the truth — that their lives mean little to those in power — hardening what had previously been only a lingering, general suspicion into something more concrete.

In March this year, Mustafa Ali, the assistant associate administrator of the Office of Environmental Justice, resigned from the EPA after almost 25 years. His work had been centred on mitigating the impact of pollution in lower-income communities — communities like Flint, in fact — and even then, his agency had been roundly criticized for not doing enough. Flint was one of most high-profile examples of environmental injustice (the Dakota Access pipeline is another) under an administration that at least appeared to be interested in ameliorating the plight of at-risk communities. Now in the era of President Trump — with his seeming disdain for the work of the EPA, and a wish-list budget that featured swingeing cuts to the agency — questions arise about what environmental justice will look like in the years to come. But in the meantime — as no one has been formally convicted of any crime as of writing — a lingering question remains for the residents of Flint: Will they be able to trust their elected officials — local, municipal, and gubernatorial — ever again?

If the answer is yes, what, precisely, would it take?

Danielle and Christopher Kabel are still getting used to life with their little one, a friendly and very noisy 9-month-old named Adara. The couple, who met in high school, had been living with Danielle’s parents in Flushing, a city just west of Flint, but recently moved back to an apartment in the city. “I turned on the faucet in the bathroom sink, and sure enough, it came out brown,” Danielle, 24, says with a smirk. “I had forgotten that we had to worry about the water in Flint until I turned on that faucet.”

We are sitting in the basement space of Veterans of Now, a nonprofit enterprise on Court Street that provides veterans with information and access to their entitlements. The proprietor of VON is George F. Grundy II, a soft-spoken former Marine whose description of returning home from Afghanistan boils down to a few firmly uttered words: “I didn’t have plans on getting out, but you know, life happened, and it was time to leave.” He started VON because he’d been in need himself. “When I got out of the military, I found myself without shelter; I was homeless,” he says as he helps himself to some of the communal loaded nachos in the centre of the table. “So once I got into a position from where I could help, I created the organization to do such.” By the time he moved in, the water response in the city was underway. “I moved into my home February 29, 2016, and from that day to this, I've had water on the location for people, for the community to have access to.” He calls his place “a warehouse” and works with local organizations to offer work to young unemployed people, which during the crisis has meant water delivery. “It's just trying to make a horrible situation tolerable. I just do what I can, day to day. Just...do deliveries, and create opportunities for people to be able to work, to be encouraged.”

Around the table are other young Flintstones: Jordan Paul, 21, and Tony Atlis, 31, who sit near the Kabels and dig into the nachos as well. Before we start talking about Flint, we all discuss the merits of a catastrophe-imposed reset button, inspired by Kathryn Schulz’s 2015 New Yorker article about a super-earthquake in the not-too-distant future. Atlis (who clearly enjoys playing to an audience) believes it’s the only way humans will learn; Paul, younger and more optimistic, is less convinced.

On the topic of Flint’s water, though, both men are similarly appalled, and thinking of the ways poisoned water might affect them — and the youngest members of their families. Atlis has a 3-year-old daughter; Paul’s nephew is 2. The two men have spent most of the crisis worried about them. “When my daughter's home,” says Atlis, who delivers water throughout the city, “I can't give her a bath in the water because it can affect her little immune system.” That’s because, he says, his own skin was affected by the tainted water: “I noticed that I had a body rash from my neck down — just real fine bumps — all over my body. Then it turned from that to a, like, a big, almost like a scab. Like scales on my body — it was itching and hurt. I was like, maybe I got eczema or something, but then they began talking about the water crisis.”

Atlis has strong words for the people who let this crisis happen. “I think they should be punishable by death.” When the others around the table recoil sharply, he shrugs.

Chris Kabel pipes up: “Waterboard them with the water from our river?”

“I'm just being honest with you,” Atlis continues, “because actually if you think about it, that’s…”

Danielle Kabel interrupts to finish his sentence: “...kinda what they're doing.”

“Right,” Atlis says.

The Kabels have an informal deadline set on when it might be time to leave Flint. “It's only a matter of time before, if they don't fix the problem, I'm getting the heck out of here,” says Chris. “’Cause I'm not gonna have to deal with her [he gestures at his daughter] growing up 18 years — it's already been three — dealing with this.” He fears his home city may be the first domino, and describes it as the “ground zero” of high lead in the water supply. “They're finding out all over the country that it's not just Flint — it's multiple cities that are dealing with problems like this, that are having high lead levels. We sit here and have to be told, ‘Okay, your water's at a safe drinking level of lead now’” — he raises his voice incredulously now — “there shouldn't be no ‘safe levels’ of lead in your water!’” The others laugh and murmur in agreement.

But his wife has other concerns, too. They’d like to add to their family in the future — she’d love a little boy next — and as she sees it, the water is only one of a list of the city’s problems. “Education is a bad enough issue as it is,” she says. “They're steady closing schools and stuff like that. But the water on top of that? Like, we can't keep going, living off bottled water. It takes a lot of water to run a bath for a child. And as she gets older, that's going to be more water.”

She laughs as she bounces Adara on her knee. “Can't keep doing that. If the only option is to leave, that's the only option.”

Flint is a city whose fortunes were built on capitalist industry: Lumber gave way to GM (and the automobile industry), and then...not much. It earned a reputation as a hotbed of violent crime following its economic downturn. For most people, Flint was best known for its starring role in Michael Moore’s 1989 documentary Roger & Me, which followed GM’s decision to close several plants there. Walking around the city in 2017, however, is a little sadder: The quiet slide from being the beating heart of an entire industry to a place where the water is unsafe for human consumption feels apparent in every square foot. What’s been going on in Flint for years reminds George Grundy of a structured military action. “To conquer an area,” he says quietly, “mess with their economics, you deal with their food, and you tamper with their water. Those things right there, they kill the community; it kills any type of opportunity for them to fight back or to sustain themselves. So with all the compounded issues that Flint is dealing with…” He trails off. “We're number one in a lot of bad things, like crime: We're in the top five when it comes to crime. When it comes to the poorest communities, we're in the top 10. When it comes to anything negative that you wanna say about American society, we win. We're competitors for the gold.”

Around the table, his fellow Flintstones nod soberly. Since the 2002–2003 academic year, more than 20 schools have closed, almost half of them in predominantly black neighbourhoods. The population of the city has been steadily declining since the 1920s, according to census data. (Its peak was in 1960 at almost 200,000; it's just under half of that today.) For years, breathless crime reports told of Flint's reputation for being especially violent; in both 2010 and 2012 FBI figures showed it had the highest murder rate among cities with a population of 100,000 or more. (It fell out of the top 10 most violent cities in the US last year; local police figures released last May suggested homicides were down 32% year-on-year.) Flint verges on being an urban food desert, with lower-earning residents having less access to healthy food options, although since moving to the more accessible location of the old Flint Journal premises, the city’s vibrant farmers market has seen an uptick in the number of poorer residents who come to shop. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the city’s unemployment rate at 5.4% in March this year (nationally, the rate was 4.5%), and the median household income in the city is $24,862 (compared with a state median of $51,084 and a national median of $55,775).

Flint has its problems. It certainly did not need a water crisis.

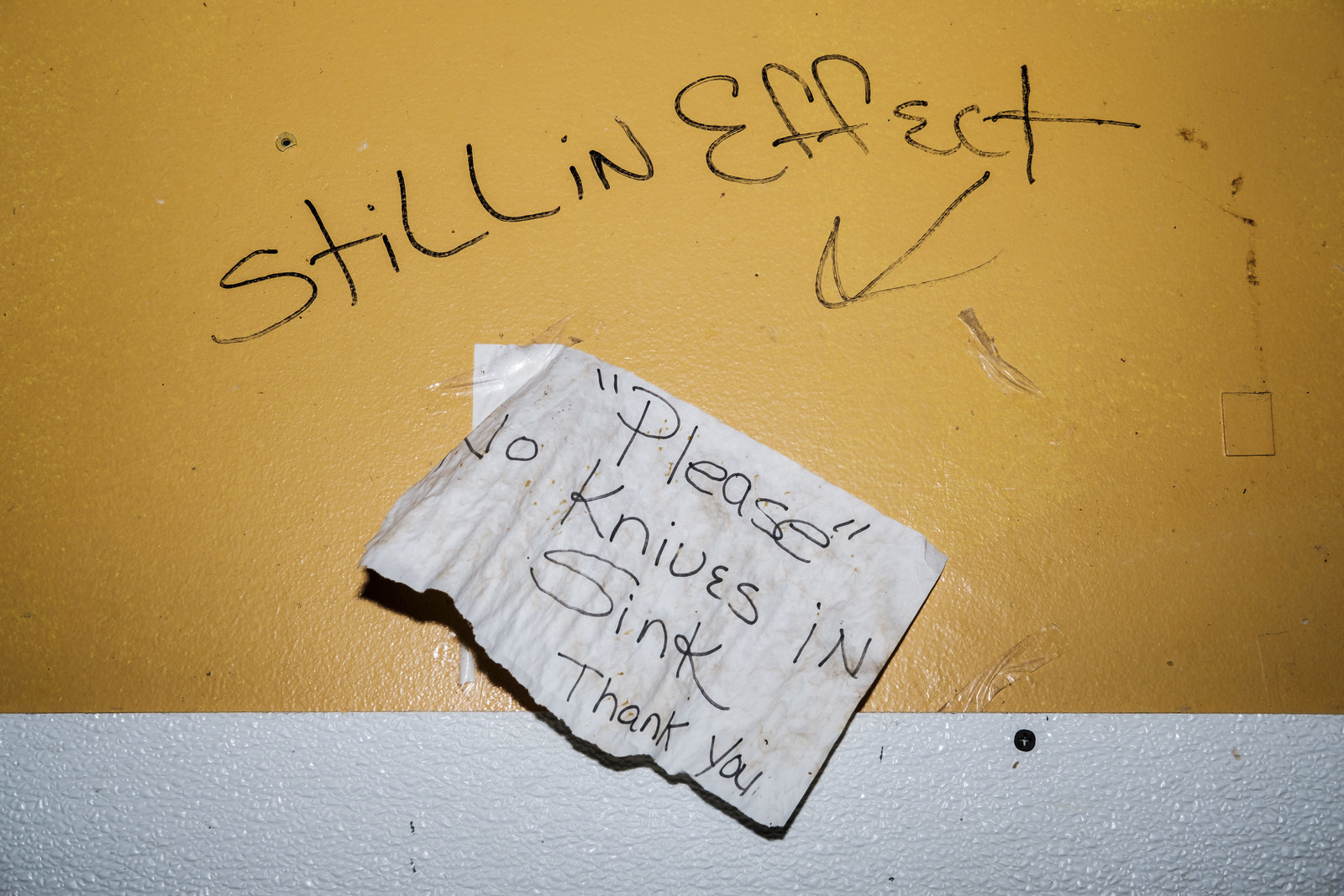

If you’re in Flint these days, it is impossible not to think of water — and everything that water touches. There is no relief from the thought of it: Pulling off the highway and heading to a hotel downtown, you can spot the signs for water distribution centres. At the hotel check-in, the traditional ornamental basket of health-giving fruit on reception desks the world over is absent; instead, there sits a basket of bottled water. The receptionist smiles as she mentions the four complimentary bottles of water in my room fridge, before telling me I can come and get more anytime, and helpfully points out a machine pumping out seven-times-filtered chilled water just opposite the lifts. Thinking about water this closely is an enforced hobby here, and before long I am caught in its thrall. Upstairs, I brush my teeth with bottled water — reminding me of my years at boarding school in Nigeria during the ’90s — and when I shower I get just wet enough to lather, and again to quickly rinse off, mouth grimly sealed the whole time. I eat peelable-only fruit and decline polite offers of water at every meeting I attend. When a small, blister-like irritation springs up on my right leg a few days later, my first thought is of the water. I snap a photo of it — just in case, I think. My already-splintered trust breaks even further in my few days in town; imagine this cycle, multiplied endlessly over these many months, for the population of an entire city.

Water as a preoccupation is not new in Michigan. On some level, everyone understands water’s place in Michigan’s ecosystem (economic and otherwise). This is the Great Lakes State, among other things, as well as one of those regions of the country where industry is woven into the cultural fabric — along with the attendant industrial waste. So water, clean or dirty, is a constant and enduring Michigan concern; anxiety about its cleanliness and potability is old hat. (A friend from the Great Lakes Bay region not-so-fondly remembers childhood fears about Dow Chemical, and dioxin levels.)

The intense focus on their city over these last couple of years has given Flint residents a distinct air of media training when you talk to them: Their responses have been dulled by endless months of repetition to a sort of flat patter. They’ve read the articles, they’ve watched the news, and they are tired. Even so, there is still an eagerness to talk about it, to make sure they haven’t been forgotten, to hold someone — anyone — to account for what they see as unequivocally unjust.

On 17 February, the Michigan Civil Rights Commission (MCRC) published a 131-page report, The Flint Water Crisis: Systemic Racism Through the Lens of Flint. In a summary, the authors of the commission write, “We believe the underlying issue is historical and systemic, dates back nearly a century, and has at its foundation race and segregation of the Flint community.” However, they are quick to remove the suggestion this racism came from racists in Flint today. (“We are not suggesting that those making decisions related to this crisis were racists, or meant to treat Flint any differently because it is a community primarily made up by people of color.”) The “top” notes are as follows: Implicit bias and racism played a part, baked in as they are to Flint’s history of segregation along housing and education; so did the emergency manager law, which essentially overrode locally elected officials and likely exacerbated the crisis.

"There's not a day that goes by that I don't think about pushing the button to go to the Flint River, or drinking the water on Channel 5. I regret that that happened every single day."

Reiterating a conclusion reached by the governor-commissioned Flint Water Advisory Task Force in March 2016, the commission said the crisis was an act of environmental injustice, adding, “had the emergency manager law focused on the financial health of the city and the welfare of its residents, and not just on cost-cutting measures, and/or had it allowed for meaningful involvement of the community when it came to the very basic needs of life, clean water and clean air, this too could have served to mitigate or even prevent the water crisis.”

An extract from the state’s own press release, published on its website after the report came out, boiled Flint’s issues down thusly: “historical, structural and systemic racism combined with implicit bias led to decisions, actions, and consequences in Flint [that] would not have been allowed to happen in primarily white communities such as Birmingham, Ann Arbor, or East Grand Rapids.”

Having been in office since August 2009, Dayne Walling was the mayor of the city when the switchover to the Flint River was made. He lost his re-election bid in November 2015 to Karen Weaver, the city’s first female mayor. As with all things politics in 2017, it’s difficult to say if he would’ve held on to his seat in a city without an acute and ongoing water crisis. But it’s true that in July 2015, then-mayor Walling did his weekly appearance on local TV channel WNEM and, while on air, drank water drawn from the faucet in an attempt to prove it was safe for residents to drink. “It's your standard tap water,” he said on camera, before adding, “You can taste a little bit of the chlorine.”

These days he is regretful of that moment. “There's not a day that goes by that I don’t think about pushing the button to go to the Flint River, or drinking the water on Channel 5,” he says when we speak. “I regret that that happened every single day. It was honest of me to drink the water, because my family — my kids, my parents — we were drinking the water. I trusted that the water met the standards. And I believed that the problems we were seeing were in individual households, as a result of the ageing infrastructure, and I was working every day to try to address the problems as I understood them.” He clasps and unclasps his hands as he pauses. “And then to find out, a few months later, that there’s this underlying problem, that the corrosion control wasn't only not being done, but had this terrible effect leaching lead into the system? You know, thousands of kids, thousands of seniors being affected citywide. So I regret those actions. Every day I carry that with me.”

We’re speaking at Walling’s home, where he lives with his wife and children. He seems sincere, which inherently makes trusting him difficult — the aphorism about faking sincerity comes to mind but doesn’t stick. He still lives in the city, and even now, without his mayoral title, appears to care deeply: He has a thoughtful face, and it’s not hard to imagine him spending long hours thinking about both that ill-fated TV appearance — and the crisis as it keeps unfolding — all this time later. On the issue of trust, Walling often returns to one word: transparency. In order for the people of Flint to believe they are sincerely cared for by the powers that be, they have to see it. “It takes time,” he says. “We learned that information was mismanaged, that information was deliberately manipulated and filtered before it got to us here in this community, and it was clear to me that it would take a long time for that trust to be rebuilt. People have to see information and actions and priorities all aligning, not for one week...but for years and years.” Why, for example, he asks, isn’t there a centralized, consistently updated service that details exactly what is being fixed in the city’s water system?

“I'd like to be able to go on a map online and be able to see the services that have been provided to every household and every family here in the city, and be able to see what has been done, what hasn't been done, what's planned to get done,” he says. “People need to be able to go and see for themselves what's happening on that block of Brownell, what's happening on that block of Fenton Road.” It would be a massive undertaking, involving all levels from city to federal government, as well as volunteer organizations, but Walling thinks it would be worth it. “If we keep talking in generalities, then people aren't going to be able to trust those kinds of broad statements.”

The day before, I’d met state Sen. Jim Ananich at his home, interrupting time with his young son, Jacob, whom he only semi-successfully distracted with Sesame Street for the duration of our conversation. “I don't know what it would take,” he'd replied when I asked how trust can be restored to the people of Flint. But like the former mayor, he believes it starts with the pipes, and he touts the benefits of total transparency. “They always seem as though they're trying to get ahead of a press story. And until they stop doing that, no one's gonna believe them. I told them a year ago, told people in the governor's office, I said, 'This is going to sound crazy but what you should do is start telling the truth.' And nobody argued with me.”

On a visit to the beleaguered city in April 2016, Governor Rick Snyder (now on his second term, and therefore ineligible for re-election at the 2018 gubernatorial election), promised he would drink Flint water for a month to prove how safe the water was. (No one seems to have followed up to confirm he kept this promise.)

Last month Ananich released a statement saying, “My city was poisoned on April 25, 2014 — three years ago today. To this day, we are still reeling from the devastating effects of reckless emergency management and a state government that failed to keep us safe.”

The anniversary marked the city’s 1,097th day without clean water.

At the headquarters of the United Way of Genesee County, a nonprofit in downtown Flint, I speak with Jamie Gaskin, the CEO of the organization. He is an affable, helpful sort of man, who speaks with a relaxed drawl reminiscent of Hollywood actors Owen Wilson and Jere Burns.

Gaskin and the United Way stood with Dr Mona Hanna-Attisha in 2015 when she announced the results of her research into lead in Flint’s children, responding to the emergency by buying filters, and water by the truckload, to get to the most at-risk residents: pregnant women and people with immune deficiencies. The wariness residents feel, Gaskin contends, stems from a lack of transparency from the city and state officials. “Fundamentally, there's this mistrust because of all the uncertainty around who knew what when, and who was truthful and who was not,” he says. The confusion over timelines and information is a potent driver of suspicion.

“There are many people that don't trust the government, or the experts, then they've lost all this value [in their homes]. There are people who clearly have symptoms or things that have happened to them where they can say, 'Look, this has happened,'” he says. “And then there's the unknown health problems.” The worst of it, however, is what remains truly unknowable. “The majority of people, I think, are sort of in this mystery area, where you've had an unknown exposure over this year-and-a-half period of time where the water was coming from the Flint River, and you don’t know what the health consequences are going to be, other than looking at what data says lead exposure does to you over a lifetime,” Gaskin continues. “And those things are simply not good: lower IQ for children, folks with immune deficiencies having a problem…” Earlier this year, the CDC found a genetic link between an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease between 2014 and 2015 and the city’s water.

Gaskin is a Flint resident himself, and bought a house in the city 15 years ago. He has a chlorine filter installed in his shower, and while he will also drink the filtered water, he admits he prefers bottled. “The residents are faced — I'm faced — with looking at this thing, going, ‘Who do I trust?’ I really look to the scientists and the experts to tell us the truth. But emotionally, even when they're looking at you and telling you, and you believe them, it's hard to just...drink the water,” he says. Sen. Ananich echoed Gaskin’s sentiments. “I don't trust 'em and I'm part of it, technically. Right?” he says. “I've seen too many examples of where I have proof that they lied to me, through emails that have come out. Communications I was having with them, they were saying everything was fine and they were communicating afterwards, saying, ‘My god, this is terrible,’ but they didn't tell me that, knowing that I lived in Flint, and I had a 19-month-old.” He shakes his head.

“I think we have a long-term problem,” says Gaskin. “There'll be a lot of residents, a lot of kids probably, who will ask questions every time they drink water for the rest of their lives. Those are these kind of things that are gonna drag with us for years and years.”

For the next few or several years, filters will be the only way for Flint residents to live and use the water being pumped into their homes. “Learning to trust that a filter really does what it's supposed to do is critical to us moving forward," Gaskin says. "At some point the mass distribution of water is likely to stop; we're gonna get to some point in the future where bottled water is not going to be everywhere and what's going to be left for us is filters. So it's going to be critical that residents learn to trust those filters.”

Here’s what Gaskin wants to stress: The water is still not fit for consumption without human intervention at the faucet end. “The water has returned to what the state would describe as ‘normal’ levels but because there’s going to be so much disruption to the system over the next three years with all the digging up of the thousands and thousands of pipes, we won’t be able to drink the water unfiltered, probably for three or four years.” As if to make sure I’m grasping his words, he repeats himself, this time with a level stare.

"I don't share the 'if I could, I would leave' [narrative] because I believe Flint is the canary in the coal mine."

As the MCRC report noted: “Flint may yet have another water crisis as, even when this contamination is gone, the pipes replaced, and the water safe, its price will likely be beyond the financial reach of many of Flint’s residents, but the impact of this crisis will, both physically and non-physically, be long lasting.”

Until March this year, Isaiah Oliver was the vice president of community impact at the Foundation for Flint, a charity that “raises and distributes resources to serve the long-term health and development needs of Flint children.” He looks like a younger, more bookish Will Smith and is a proud Flint resident who wants to see this problem entirely resolved. I ask if he would move if he could, like some of the other people I’ve spoken to. His answer is long and passionate.

“I don’t share the ‘if I could, I would leave’ [narrative] because I believe Flint is the canary in the coal mine. I love urban centres. I would be in a city just like Flint, and I would be afraid if I were drinking the water in Chicago. I’d be afraid if I were drinking water in Cincinnati, or in Houston. Because they could have the same issues that we have right now. And so I don’t believe that if I left and went somewhere else that life would just be different, and I'm willing to be on the front lines of trying to address the issues at home.” Addressing and overcoming those issues will take time, which is a luxury Flint cannot necessarily afford. “[People] are making that decision to leave, because they’re afraid, and rightfully so.”

Like many residents, Oliver struggles with the guilt that he might have inadvertently allowed his children to drink tainted water. “For the first year and a half of this, that was the time my now 3-year-old was actually using bottles, I was taking it straight out of the tap because the government said it was okay. And I was shaking up the formula," he says, miming the shaking of a bottle, "and I was giving it directly to my daughter. Grassroots groups were pushing information to the forefront about this water not being safe and I was saying, ‘Ennhhh, just calm down, we gotta trust the system; we don’t have any reason not to trust it.’”

“So when my [older] daughter comes home with a cold or the teacher says she’s counting by twos but her counting by fives is slower, I’m thinking [he sucks air between his teeth]. Part of me wants to say that this is just normal. But part of me as a parent says, Is that because I allowed my daughter to drink the water?”

Those thoughts are going to keep cropping up for the parents of Flint for the next few decades. According to Save the Children, there are about 26,000 Flint children for whom lead poisoning is a threat, and one January 2016 piece in the Detroit Free Press had the number of children under 6 in the city at 8,657, based on census data (and admitted this could be a conservative estimate). Once someone is exposed to lead, it is only detectable in the blood for 30 days, so blood tests taken after that time may not reveal the full extent of exposure in the city. This is the realm of “the unknown,” as the United Way’s Jamie Gaskin put it. And the lack of clear and precise information around who drank what when makes for a mess. It may take years for the effects of lead to show up; how do you go about remedying a problem when you are not even sure what your child may have been exposed to? What parents and caregivers can do, though, is read, and watch television — and what they have been told from day one is that high levels of lead in children have grim consequences.

At the time the results of Dr Hanna-Attisha’s study came to light, she said, unequivocally, “Lead poisoning is irreversible. This is not what our community needs.” In a 2016 interview with CNN, she said, “There is no pill ... no antidote for lead.” The EPA names the health effects of lead in children as follows: “behavior and learning problems, lower IQ and hyperactivity, slowed growth, hearing problems and anemia.”

Even so, there are things people can do to alleviate lead absorption, starting with a diet high in vitamin C, iron, and calcium. Over at Mission of Hope, a small church about 15 minutes’ drive from downtown Flint (and also the first organization to start handing out water on a continuous basis, back in September 2014), Pastor Bobby Jackson shows me his little community garden (the church has four garden plots in the vicinity), where the congregation planted vegetables to stall lead absorption in his community’s children. It's called the Garden of Love, but there are three more small garden sites close by. “We live in a food desert here in Flint. Last year, because of the water crisis, [we grew] dark, green leafy vegetables — collard greens, kale — things that would help absorb the lead. But normally it’s just fruits and vegetables.” He shows me a plum tree and tells me of the cherry trees that bloomed last summer. “Our goal is to provide a self-sustaining ministry for the homeless, the poor, and the mentally different,” says Pastor Bobby, which is how everyone refers to him. “The water crisis added another dimension.”

Sen. Ananich touts the programs available to parents. “A number of really great programs” — like Head Start, and those under the Flint Child Health and Development Fund umbrella — “are out there that can really sort of assess if there was damage done and then help remediate it. We don’t have to assume these kids are some throwaway generation. Love your kids, make sure your kids get good nutrition, don't assume that they're going to have lifelong problems — and if they do, there's things that we can do to make sure that they get the help.” His own son, Jacob, was born “right during the crisis,” in July 2015, and because he was adopted, Ananich is in the dark as to what his exposure to lead-tainted water might have been. “I have no idea what his prenatal care was. So, you know, it's one of those things where we...a lot of folks, I mean, myself included, we’ve all gone through it. It's sort of stages of emotions. So there's that feeling of like, did I not do enough to protect my own family? There’s anger. A lot of anger, a lot of stress.”

Gaskin of the United Way tries to be optimistic about the future of an entire generation of Flint’s kids. “The world needs to know that there are thousands of gifted children growing up in Flint, that will continue to be gifted and wonderful people,” he says. “This is not a community that is sort of steamrolled, like, lock the doors and go away, you know.”

He speaks enthusiastically of an initiative the UW is a part of, called Flint Kids Are. “[Flint kids are] bright, resilient, healthy. We need to really make sure that we push a narrative that acknowledges the problem and tries to help people become as whole as possible, but also really recognizes the richness that still exists here,” he says. “There are thousands and thousands of people that every day wake up in the morning as Flint residents, love the place that they're in, and want to see it thrive.” Also working directly with kids in the city is the Crim Fitness Foundation — its community education partnership with Flint community schools focuses on social services, nutrition education, and mindfulness programs.

“We’re working with a researcher now to document the effects of mindfulness and how that helps,” says Christina Ferris, director of advancement and outreach at Crim. “That constant training of the mind to be able to focus, to calm, can actually create some new neural connections.”

Although Flint has received the bulk of media attention, it is far from the only community in the US where children have higher-than-normal blood-lead levels.

This is the point at which it is important to note that although Flint has received the bulk of media attention, it is far from the only community in the US where children have higher-than-normal blood-lead levels. In December 2016, Reuters conducted an investigation into blood test results that revealed nearly 3,000 places with worse results than Flint. It is not possible to determine the exact source of the lead in these cases — the culprits range from crumbling water pipes to lead paint — but the common denominator for much of these neighbourhoods is poverty and old infrastructure. In one California neighbourhood, 13.6% of blood tests came back positive for high lead in children under the age of 6. And in March this year, the Pittsburgh city government announced it would spend at least $1 million to provide all residents with free filters, after tests showed high lead levels due to lead in some water lines.

Perhaps the research being undertaken in Flint will mean they, too, will soon be in receipt of similar programs being offered to the city’s children. “One thing that we really do that’s the most important thing — we provide hope,” says Ferris. “Kids have felt like they’ve been poisoned, and it’s a hopeless, frightening feeling.”

The rush to alleviate that feeling also sends a secondary message, which is that Flint is a resilient city and therefore likely to bounce back, eventually. Flintstones enjoy a reputation of being a particularly hardy sort. This is Auto City, after all, and the flint of their city’s name lives in their very skin. George Grundy recalls his younger days in other cities, and how his home city commanded instant understanding: “Because I said I was from Flint, there was an instant respect — we are cut from a certain cloth.” Jordan Paul agrees. “I'm proud to say that I'm still here and I know so many people who have chosen to stay here, not out of a spirit of stubbornness, or a spirit of this is the way I'm gonna do it.” Tony Atlis says he remains in order to speak truth to power. “We need more people...that are not scared of the consequences, that's gonna point the person that's wrong in the face, and say, 'Hey, you wrong.' That's what's made me not cut and run. Plus, I'm from Flint. I mean, if you can make it here, not New York, you can make it anywhere. You know, we tough. We built different.”

Paul also notes that this renowned resilience, while helpful for day-to-day living, is also subtly dehumanizing. “It's in a new form of persecution or discrimination, but it’s one of those things where, you know, I guess, we ain't new to this!” He laughs ruefully. “Flint has that industrial culture thing [that] speaks to just being tough as nails. I'm not saying that it's right, or ‘we can take it!’

“Nobody should have to take this.”

Crystal Rheaves didn’t live in Flint at the time of the water source switchover — she moved to Grand Blanc, a suburb about 15 minutes’ drive from downtown Flint, a few years back — but she now lives and works in the city. For her, the jig was up pretty much as soon as the announcement was made. “Growing up, you would hear stories of two-headed, three-headed fish in the water. You must be fishing for sport if you're fishing in the Flint River,” she says emphatically, after we slide into a booth at La Azteca, a Mexican restaurant near downtown Flint. “We as residents in this area already knew: You don’t mess with this water. So when they told us they were going to switch the water source, my family, we all knew: I'm not messing with the water.”

A few days later, as I walked along the Riverbank Park path, I encountered two fishermen baiting their line and inadvertently backing up Rheaves’ comments: This was not fishing for sustenance. One of the men told me he had previously caught sunfish and bass in these waters. “I just do it for sport. I don’t eat it,” he said with a small, knowing smile.

Rheaves’ knowledge of and interest in the water of Flint goes beyond merely that of a civic-minded resident: She has lupus, and to avoid compromising her immune system any further than her condition already does, she tries to be very careful about what she puts into her body. In Flint, that has meant an adherence to bottled water — a habit even older than the water crisis for Rheaves — and after the crisis, has translated into a whole-house filtration system, whose efficacy she is still a little shaky on. “To some degree, in the back of my mind, I still don’t feel good about it,” she says. “Because it’s not just lead — it's other things that they add into the water that are still problematic. It seems like another Tuskegee experiment — now we have to research and we have to follow all of these children throughout the duration of their life because this is going to affect them for the entirety of their life. It kinda makes you think [like] those conspiracy theorists: How much of this was pointed to this path?” On top of all that, Rheaves can’t help but fret about the ecological impact of all this plastic. “This is even worse on the environment. People already have it hard enough in this city, just making it, day to day; do you think people have time to recycle? You think they care about recycling?”

If the city and state want to begin the process of restoring trust and faith to Flint residents, there is one thing they could do, according to Rheaves. “They can start with charging Snyder,” she says passionately. “Say we're gonna hold who's responsible responsible.” (Speaking to the Detroit Free Press last December, Gov. Snyder said he had “no reason to be concerned" that criminal charges would be brought against him.) In the meantime, residents have brought lawsuits against, variously, the state and the EPA (a class-action lawsuit on behalf of more than 1,700 Flint residents, seeking $722 million), and in March a federal judge approved an $87 million settlement from the state for the city to find and replace water lines over the next three years. However, that same month, the state of Michigan removed the city of Flint’s ability to sue the state. On the issue of accountability, Sen. Ananich is unsure of the eventual outcomes of current indictments — the attorney general has indicted 13 people so far, including former emergency managers of the city. “I can't tell if it's a political thing or if they're actually going to go after them,” he says. He’s clear on how he sees it, though. “To me, it seems like this was negligence, this was malfeasance, this was criminal activity. It's different than making a mistake. You can make a mistake, and that happens sometimes. But knowingly misleading people and all the things that they did... I think the citizens of Flint deserve ... to make sure someone is held fully responsible for that.”

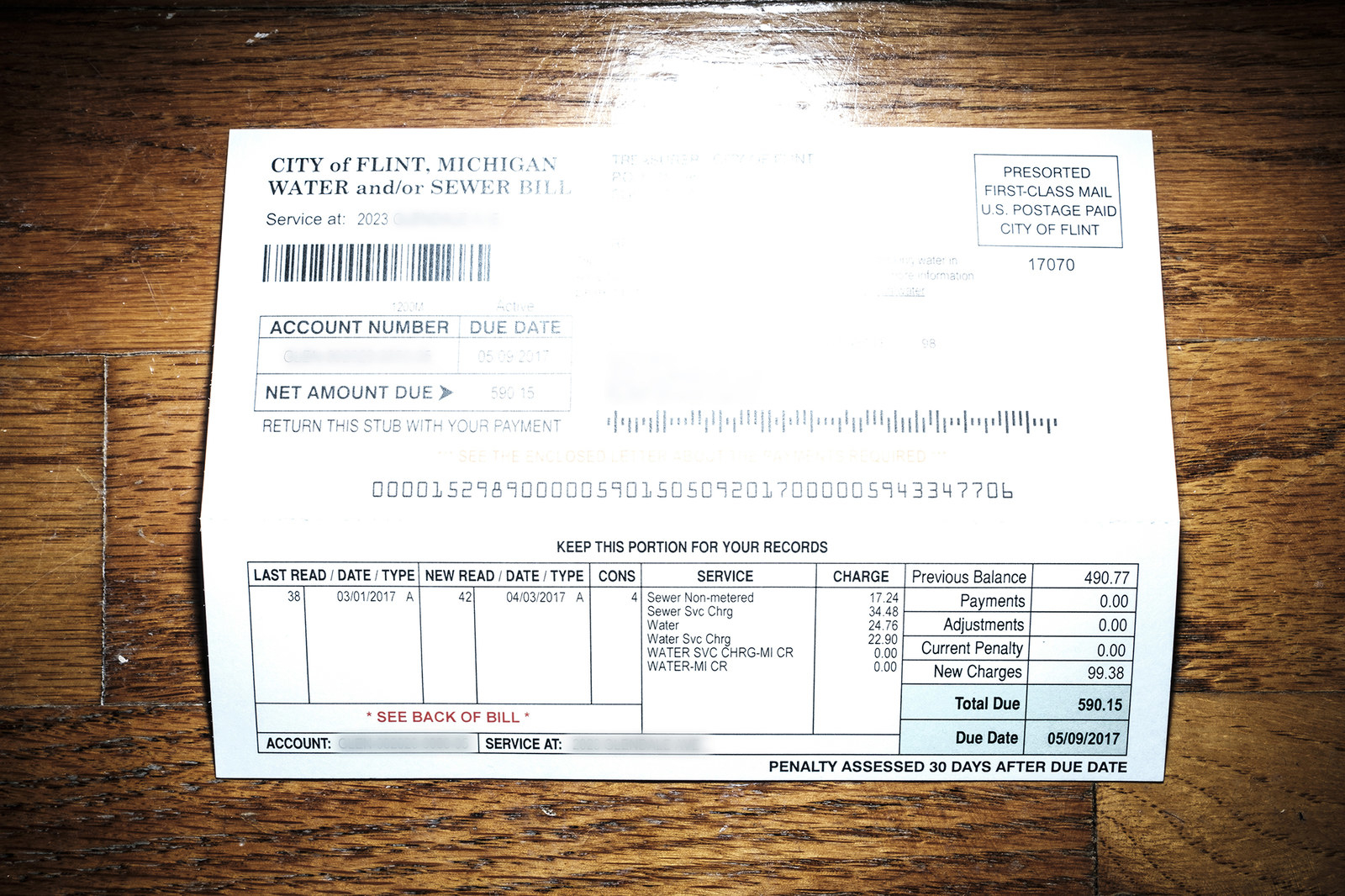

In April this year, the city sent out letters to about 8,000 residents, warning of possible tax liens (and the potential loss of their homes) for overdue water and sewerage bills. Earlier this month, city council members agreed to suspend efforts to impose those tax liens; both the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the ACLU had registered their unease, with Kary L. Moss, the executive director of the Michigan ACLU, calling the potential liens “unjust.” Prior to these warning letters, Ananich had thought trying to collect on outstanding water bills was a losing battle. “It's one of those things where people... this is what I’ve tried to tell the folks at State. You can insist as much as you want — they're not going to do it. They're just not gonna pay it,” he says emphatically. “It matters what [people] believe, and the fact they only gave us partial credits in the first place was sort of the first stick in the craw.” He accepts, to a degree, that water quality is improved overall but believes the program of water credits is ending far too soon, a view shared by the former mayor, Dayne Walling. “You continue to hear so many of us in the community saying, 'This isn't the right time for water credits to go away, this isn't the right time for the state to be stepping back,’” Walling says. “Because it's not about getting one test below a federal action level.”

“We need to be made whole,” says Ananich. “And a lot of dollars have been appropriated and that's important and I'll keep fighting for those, but we haven't been made whole yet. We haven’t been made whole on our water bills; we haven't been made whole on our infrastructure.”

Infrastructure is a constant Flint concern. Crystal Rheaves is adamant that pipe replacement projects need to be the top priority. “Come and fix the pipes,” she exhorts plainly. “[Snyder’s] talking about a surplus in Michigan or whatever. We still need our pipes fixed, OK? It shouldn't be a year, two years later that you started digging up the pipes.”

In March this year, the city awarded contracts worth $35.6 million to replace 6,000 water lines — the largest of which ($10.98 million) went to W.T. Stevens Construction, a black-owned firm.

But Rheaves believes Flint’s problems go beyond poisoned water, even if that’s the most pressing issue on the table. “It's like, there are so many different things they would have to do to restore trust. You can't even start with just the water: I have no trust in our government to say, ‘We care about your education, your children’s education’ — just basic, general things. I can’t trust you to do anything for me when you’re saying you’re gonna cut money for this and that, [but] you're spending money doing things that don’t even…” She cuts herself off, her voice higher and more impassioned than it had been at the beginning of our conversation.

The gleaming promise of Flint’s past has faded over time, as the automobile industry at the core of its economy has wound down. The very technology that so excitingly revolutionized and grew its fortunes has in many ways eaten itself. The city has instead been beset by the usual suspects that come with a big bust after a big boom; economic downturns hit black Americans harder than most, and the majority of Flint's residents are black.

The MCRC never used the phrase “environmental racism,” but it is a conclusion other people have already reached when it comes to describing the issues that caused and exacerbated the water crisis in the city. It’s a mantle a generation will be forced to carry. Sen. Ananich is already looking to that future. “There's a lot of things that keep me up at night,” he says, “but the fact that we're going to look back 20 years from now and that's going to be...that basically their government told them it's okay to be treated differently because of their skin colour, because of their income or because of the fact that they live in an older urban city, that's just not acceptable to me.”

He talks of the stress and anger in his city’s residents, which is “100% justified,” even as he recognizes it often feels impotent. “But a whole community living in stress and anger and frustration, even though it's 100% justified, it's just not effective for the community. There's times when I'm just furious about what happened to us, the fact that it's taken so long to get... It's termed a crisis, right? We're almost three years in and we refer to it as the ‘Flint water crisis’ every day. There shouldn't be a ‘crisis’ going on for three years. If this was Bloomfield Hills, or Beverly Hills, California, this would not be happening now.”

For all the environmental justice work that gets done at local levels, all cues inevitably are taken from the federal government’s actions, and recent developments do not paint a rosy future. Only hours into Donald Trump’s presidency, EPA officials were instructed to freeze all contracts and grants, and in an early budget plan from the Trump administration in March, there was a proposal to cut EPA funding that goes to the Great Lakes cleanup efforts by 97%. Later that same month, the EPA awarded $100 million to the Michigan DEQ for infrastructure repair (which had already been approved by Congress and the outgoing President Obama in late 2016). In Scott Pruitt, the president has selected an agency head who has often been diametrically opposed to the EPA — when he was the attorney general in Oklahoma, Pruitt sued the agency 13 times. Even with the promised money for Flint, if faith in the effectiveness of the EPA is at the heart of people’s pursuit of environmental justice, it must have taken a big hit over the last few months.

As we wind down our conversation, Rheaves sums up the problem as she sees it: If the lives of Flint residents genuinely mattered to the US economy in a tangible, measurable way, the response would have come sooner. “They don’t care. They’re not making it a point to get it fixed, because like I said, this area — we're not producing cars like we used to back in the day. It's not like we're producing something they need. We don't have anything that's demand-worthy to that degree that we're gonna matter in any sense. It's like, what incentive do they have to help us, besides doing the right thing? Doing the right thing obviously means nothing to them.” ●