He wrote me a letter. That’s how we met. He had read my book The Anatomist in proof, and enjoyed it. (“I meant to provide a blurb,” but “got distracted and forgot” — an admission I found charming.) This was when I was still living in San Francisco — in early 2008. This was when people still wrote letters regularly (which was not that long ago), and when one got a letter, sat down and wrote a letter back.

“Dear Mr. Hayes — ”

“ — Dear Dr. Sacks...”

Thus, a correspondence between O and me began.

My decision to move to New York more than a year later had nothing to do with Oliver, and I did not have a relationship in mind. I had simply reached a point in my life where I had to get away from San Francisco — my home for the past 25 years — and, at age 48, start fresh. But once I moved here in the spring of 2009, O and I started spending time together and quickly got better and better acquainted.

5-9-09

O says I must keep a journal.

And so I must.

I make notes on scraps of paper, the backs of envelopes, cocktail napkins. Sometimes dated, sometimes not.

6-17-09

“Are you seeing anyone?” someone asks.

“Only New York,” I answer.

This is not 100% true.

O isn’t comfortable with anyone knowing about us and gets palpably nervous if we are out together and see someone he knows.

12-26-09

O, on the phone to me, stutters to speak: “I know that I put up all kinds of restrictions. Barriers. And was reluctant to go places with you in public. I now want to say that I love you, too, and I would be happy to go anywhere with you.”

I am smiling broadly on the other end of the phone.

“And I, with you, young man,” I tell him.

2-1-10

A languid Sunday, afternoon turning into evening, evening into night, night to morning.

“I just want to enjoy your nextness and nearness,” O says.

He puts his ear to my chest and listens to my heart and counts the beats.

“Sixty-two,” he says with a satisfied smile, and I can’t imagine anything more intimate.

8-17-10

I stop by O’s to bring him an ice cream bar. I mention I saw fireflies in Abingdon Square Park — fireflies!

O: “Did you keep your mouth shut?”

I: “What do you mean keep my mouth shut?”

O: “They say three will kill you — luciferase, dangerous stuff.”

I am laughing, but he is not. I really cannot tell if he is serious.

O: “I don’t want you to die of fireflies…A luminous death!”

8-26-11

We are at the Brazilian restaurant, when O suddenly asks: “Have you ever felt that a part of your body was not yours?”

I laugh. “This is why I love you.”

He smiles. “Well?”

“A part of my body not mine: Uh, I’m not sure, I don’t think so.”

“If one did, one would know,” O responds drily.

After eating, we rush back to his apartment to listen to a live broadcast of Mozart’s Requiem on the radio. Or, what we thought would be. It was Schubert instead. Ah, but Schubert — so Romantic and grand: Lying on the bed in the dark, listening to his eighth symphony, in our underwear.

The radio announcer says that Schubert died at 31.

O: “Do you think it makes it easier to die young, knowing that you have already created enough masterpieces for a lifetime?”

I: “No, no I don’t.”

9-15-11

7:15 p.m., O on the phone, without even saying hello: “Billy! Shouldn’t one be on the roof? The sun is setting!”

I: “Yes, one should!”

O: “I will meet you there!”

I: “I will bring a bottle!”

1-1-12

Just before midnight, I taught O how to open a bottle of Champagne, something he had never done before: Sweet to see the joy and surprise and fear on his face as — pop! — the cork exploded. He had insisted on wearing his swimming goggles, though, just in case.

3-17-12

O: “I don’t know if a passion for symmetry is an intolerance of asymmetry. Do you?”

I: “I think one can be passionate about both. I think one can embody both.”

O: “Good. Very good.”

4-7-12

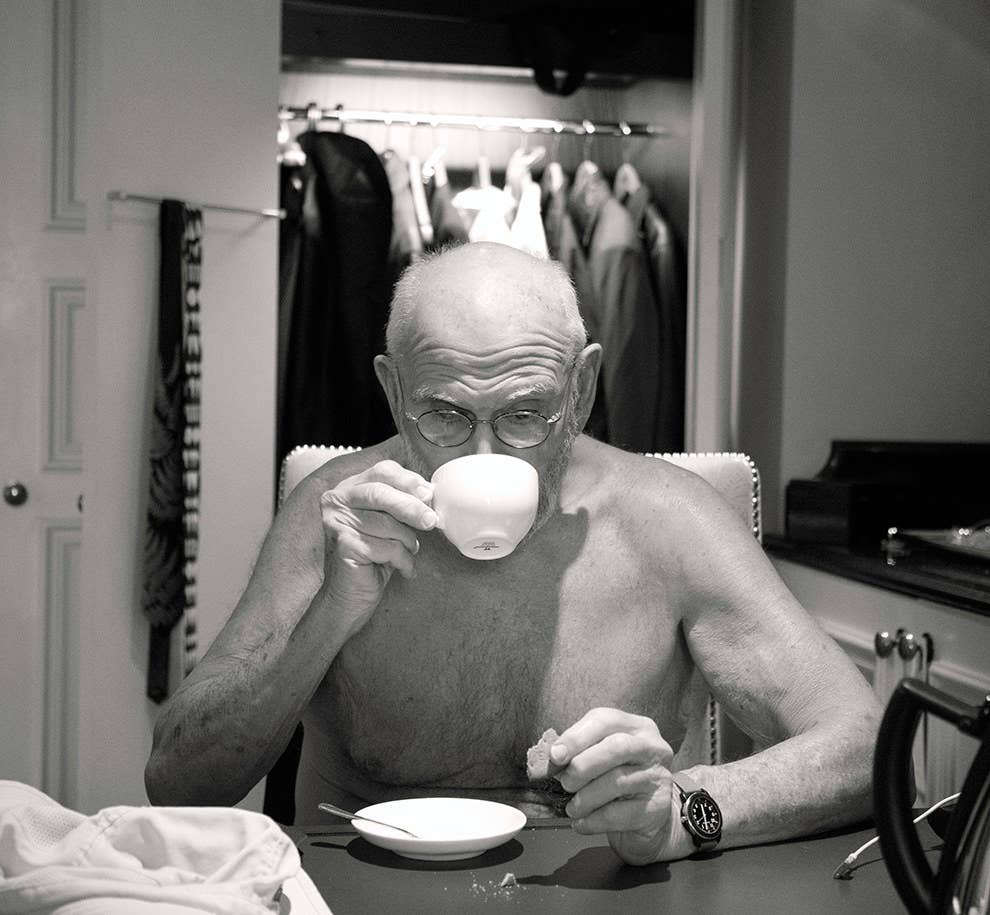

A not untypical dinner:

O snipped the ends off the string beans with his cuticle scissors, “coiffing” them for the steam. I trimmed the broccoli. We shared a gigantic carrot, passing it back and forth between us, while having some of O’s specially mixed tea — a blend of smoky lapsang souchong and brisk Darjeeling.

We left the salmon to marinate. I read the paper, O went into the bedroom and did 55 of his signature crunches — exhaling on the first, then holding it five seconds on the second. O likes things to be in fives. I grilled the salmon atop the stove, five minutes each side, and made some toast from leftover Challah bread.

I opened a bottle of wine.

I was feeling blue, I didn’t know why.

To divert me, cheer me, O told a story of a Tourette’s patient who was a surgeon and would smoke while exercising every morning. This made me laugh; I hadn’t heard it before. After eating, O got up and found the story in An Anthropologist on Mars — his large-print edition. As I lay on the couch, he sat at the table and read the entire story, from start to finish, in the most animated voice, lavishly drawing out the more unusual words. I peeked over the couch a few times to watch him reading, the book just a couple inches from his face. It’s amazing he can read at all — he’s so nearly completely blind. I clapped when he came to the end.

We returned to the kitchen. His wine was “too sour,” so he added a packet of artificial sweetener to it — “much better” — and drank it down. We talked about this and that, and then I said I needed to go to bed. He absentmindedly reached for the bottle of port, uncorked it, and took a swig. “Nothing like port,” he murmured.

Next morning, O reported that he had had a dream in which he was at a “charming little café in the shadows of two giant oversized mushrooms.” On the menu? “Two kinds of fern salad and a carrot salad with 7,217 different carrots.” He’d drawn the number (and a picture of the mushrooms) on the kitchen white board when he woke in the middle of the night.

10-16-13

I, soaking in the bath, O on the toilet, talking, talking about what he’s been thinking and writing — short personal pieces, for a memoir perhaps. He had brought with him two pillows to sit on and a very large red apple. He opens his mouth wide and takes a gigantic bite. I watch him chewing for quite a while. After he finishes, “Bite me off a piece,” I say. He does so, dislodges the apple from his mouth, and puts the piece in my mouth. We keep talking. I add more hot water. Every other bite, he gives to me.

There is a quiet moment and then, seemingly apropos of nothing, O says: “I am glad to be on planet Earth with you. It would be much lonelier otherwise.”

I reach for his hand and hold it.

“I, too,” I say.

6-3-14

Sunday: O nuzzled his nose, dog-like, into the side of my head, brushed it up and down and back and forth against my buzz-cut hair (“It’s like a meadow,” he said) and then he did so with the top of his head.

“Now, why does one do that?” O said, suddenly the scientist in him coming out.

“Because it feels good,” I answered instantly.

He laughed; it was such a simple and seemingly simplistic answer.

“But that’s very interesting,” O said, picking up this thread. “Does feeling good — does feeling — influence all of our choices as animals? Something feels good, so we do it again — this is how we learn about pleasure. Or it doesn’t feel good, so we learn that it carries a risk, a danger…? Are our lives ruled by feeling?”

“Mine is,” I responded.

He didn’t seem to hear me. “Do plants feel?” O said.

He looked at me like I held the answer, but continued on: “Certainly they do, but they cannot respond to feeling as quickly as we. Plants are rooted in the ground. They can move, yes, but not at the speed that an animal can. It may take years for a tree to grow, days for a flower to bloom. Is it speed then that differentiates us — this capacity for speed? You could do time-lapse photography of a vine crawling and see that it does, indeed, move, but one would have to speed it up a thousand times to match the speed with which an animal can react to threats or changes in the environment the way a human can.”

O tilted his head, seemingly focusing on a corner of the room. “Yes, perhaps speed is at the essence…”

9-20-14

“Do you sometimes catch yourself thinking?” says O, out of the blue, in the car, on the way to his place in the country. “ I sometimes sort of feel like I’m…looking at the neural basis of consciousness….”

“Yeah?”

“Those are special occasions,” he went on, “when the mind takes off — and you can watch it. It’s largely autonomous, but autonomous on your behalf — in regard to problems, questions, and so on.” A pause, then returning to his thought: “These are creative flights… Flights: that is a nice word.”

“Mmm, I love that word…What triggers such flights for you?”

“Surprise, astonishment, wonder...”

2-24-15

Back home after six days in hospital:

“I am going to lie down on the bed, come and talk to me,” O says.

I curl up next to him, an arm over his chest, a leg over his legs. His eyes are closed, and for a moment I think he has fallen asleep, but no: “When you can’t tell where your body ends and the other’s begins, is that primal, or signs of an advanced evolution?”

I pull him in close, his head on my chest.

“A little of both,” I whisper.

Bill Hayes is the author of The Anatomist, Five Quarts, and Sleep Demons. He is a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in nonfiction and was a visiting scholar at the American Academy in Rome. He is a frequent contributor to the New York Times, and his writing has appeared in The New York Review of Books and Salon, among other publications. His photographs have been featured in Vanity Fair, the New York Times, and The New Yorker. He lives in New York. Visit his website at billhayes.com.

To learn more about Insomniac City, click here.