In August 2008, when Pramila Aiyappa threw the javelin inside Beijing’s Bird Nest stadium, nearly 5,000km away from home, her daughter Unnathi watched and wept. The television reminded her that her mother was off some place sending sharp objects into orbit and not by her side.

“She said, ‘I want mamma right now,’” said Aiyappa, 40, over the phone from Bangalore. “It was a tough time.”

Being a new mother is tough enough. Being a competitive international athlete alongside it is a special kind of tough. When Aiyappa participated in the heptathlon at the Beijing Olympics, it was less than three years into her comeback since the maternity break.

“Initially I didn’t feel like I’m a mother at all,” she said. “I couldn’t give her time.”

So what does it take for an elite athlete to make a comeback from childbirth?

The short answer: It’s complicated.

Aiyappa eventually retired after winning a medal in the 2010 Asian Games, and had another daughter after retirement. The two experiences were completely different, but she wouldn’t have done any of it any other way.

“I sacrificed and I achieved,” she said. “I didn’t feel like I had let my daughter down. Now I give all my time to my daughters.”

As an athlete and a mother, the challenges are manifold: from physical to mental to logistical. But across the world, competitive sportswomen have been facing up to them, and winning. And it is becoming more and more common for women to return to a sporting career after having a child.

A fortnight ago Serena Williams, 35, owner of 23 grand slam singles trophies and a claimant to the title of all-time great, gave birth to a baby girl. She won the Australian Open this year while pregnant and then took the rest of the year off, but made it clear before her break that she would be returning to competition in 2018.

So what does it take to be a competitive, elite athlete whilst making a comeback from childbirth and juggling child-rearing alongside?

The short answer: It’s complicated.

BuzzFeed India spoke to four Indian track and field stars to unpack what it takes to make a post-baby comeback.

Disheartened after narrowly missing qualification for the 2004 Athens Olympics, Aiyappa had packed it all in to become a mother. But a little after giving birth in 2005, with the active encouragement of her coach husband she decided it wasn’t time to call it quits just yet. It had always been her dream to win an Asian Games medal, and she felt there was no reason she couldn’t try once more.

“A lot of people said take care of your family, this isn’t the age to compete,” said Aiyappa, who finally accomplished her goal at the 2010 Guangzhou Asian Games at the age of 33. “But I took it as a challenge. I wanted to prove myself.”

The first challenge was losing weight. She had weighed 58 kilos in her prime; three months after delivering, she clocked in at 80 kilos. But a strict dietary regimen was unfeasible since she was still nursing her child.

The physical transformation is the most obvious aspect to deal with when contemplating a comeback. It was the same challenge that Shiny Wilson (nee Abraham), faced a decade and a half earlier, in 1990. She had been a fit middle-distance runner and a star in the ’80s, but now, three months after giving birth, she felt awkward returning to the track in her new body.

“It was very difficult, but I wanted to achieve,” she said. “I was still very fast, so I thought, if I work very hard, I can do it.”

In 1994, she won two medals at the Asian Games and set a national record in the 800m the following year. The return to peak physical fitness took her about a year and countless sessions of tiring daytime workouts followed by equally tiring all-nighters tending to a crying baby.

“There’s too much to do,” said Sahana Kumari, 36, a high jumper who gave birth in 2005 and returned to win a silver at the National Games in 2006. “But you forget everything and you do it.”

Taking a break from a career in track and field – where margins are tight and an athlete’s prime is short – sounds incredibly counterintuitive on the face of it. An injury layoff of just a few months can dent performance. So how can you compete against the fastest and the strongest after spending nearly a year away from training?

“After having a baby, competing became a small thing. As a mother you go through so much, I never got scared of competition.”

Kari Bø, a sports medicine expert who participated in the International Olympic Committee (IOC) consultations on pregnancy, childbirth, and athletes said will and motivation were naturally strong factors. “Having a child may also contribute to getting life into perspective,” she said, by email. “Winning is not all, and [there is] time for relaxation, which is also beneficial.”

There is very little reliable data on reproductive effects on athletic performance at the top levels of sport. An IOC review published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine suggests that there could be short-term benefits in the first trimester, including improved blood circulation and overall aerobic fitness as the body is preparing for a new life. But there is nothing to indicate that these effects last long and how they alter performance afterwards.

“We are not sure about that, as the positive effects on the cardiorespiratory system disappear after childbirth,” said Bø. “However, some women with troublesome menstruation (pain and heavy bleeding) may experience that this disappears after childbirth, and some lose weight, which may be beneficial if it is within healthy limits.”

Physical form is one thing; girding up mentally is another. To hear athletes tell it, if there is a competitive advantage maternity offers, it is some kind of ineffable additional strength.

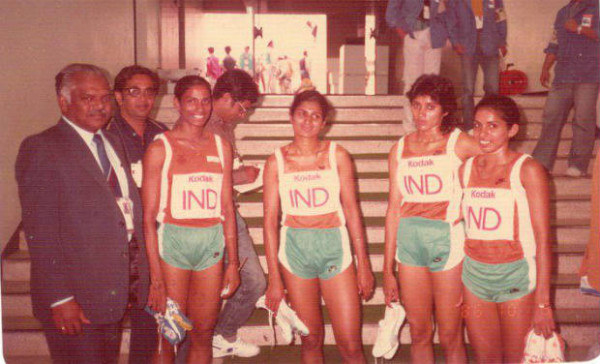

Rachita Mistry, 44, often refers to this almost mysterious force. A 100m bronze medallist at the 1988 Asian Games, Mistry returned to set a national record in 2000, wiping out PT Usha’s mark four years after her daughter Karen was born. To her mind it was entirely possible for a child and a childhood dream to go together.

“After having a baby, competing became a small thing,” she said. “As a mother you go through so much, I never got scared of competition. I knew I had to do it. I told myself, Rachita, you have to.” She said staying up at night and then competing the next day was simply the way things were.

There is no way to ascertain the strengthening of an athlete’s mental makeup, but it’s impossible to discount its very real effects on performance. And a seemingly insurmountable hurdle is often just the recipe for pushing oneself. “After the baby I became stronger,” said Kumari. “People said enough, you won’t be able to do it. But I said let me try.” Kumari later set a new national high jump record by clearing 1.92m in 2012.

Athletes have increasingly reaped richer success upon return. Tennis player Kim Clijsters made a comeback to win three grand slams, American swimmer Dara Torres returned to break her own 50m national freestyle record, golfer Catriona Matthew won a tournament when she was five months pregnant and then again 11 weeks after giving birth. Across disciplines women have been doing this, and it appears to have become more common in recent years.

“Cultural acceptance, more ways to deal with daycare, better social support” have helped fuel more comebacks now, according to James Pivarnik, director of the Center for Physical Activity and Health at the Michigan State University. Pivarnik, who has studied exercise and pregnancy, said long-term benefits from the break, if any, were perhaps mental in nature and that “as far as we know” women could return to the level they were previously performing at.

“The trend is changing now: People want to have a baby and then continue for longer.”

As athletes continue deep into their thirties, motherhood and competition are no longer considered mutually exclusive. “We have little data on this, but we think it might be [more common now], as women compete for a longer period of time (especially in endurance sports) and if they want children, this coincides with the biological age for getting pregnant,” said Bø.

In fact, having a baby earlier may in some ways help with longevity.

“Then you can plan for a longer career and there is less pressure later,” said Kumari, whose pregnancy was a surprise, and who participated in this year’s National Games at 36. “The trend is changing now: People want to have a baby and then continue for longer. Before, the mentality was ‘I can’t do this, I have to go back to a normal life.’ Now it is changing: People see others and think, if she can do this, so can I.”

For Kumari herself, watching PT Usha make a comeback after giving birth was precisely such a moment.

These women not only returned to their pre-baby levels of competitiveness, they went ahead and set personal bests or broke national records en route. To their minds, there was simply no other way. “It was my passion, sports was my life,” said Wilson. “I wanted to achieve.”

Still, there is no gainsaying the simple logistical challenges that being a mother and a top-level athlete present. Mistry and Kumari would take their children along for training sometimes. For Mistry, in the ’90s, at outstation meets accommodation for a family of three was a problem, given there were only single women hostels and it was too expensive to pay for oneself and stay elsewhere.

Then there are domestic affairs, sometimes cooking and cleaning and other quotidian tasks for which women generally tend to disproportionately bear the burden. There is the anxiety of separation, given the amount of travel involved.

Family support is crucial and all four women were emphatic about this. Mistry’s husband was a runner himself, and travelled with Mistry and their daughter, helping look after her. Aiyappa’s husband was also her coach, simultaneously pushing her on the track whilst pitching in off it, and her sister helped with babysitting duties in the early years.

But despite the challenges, none of the women would change much. “It happened by chance, and first I was a little nervous,” said Kumari, of finding out she was pregnant. “But I am happy it happened this way.”