In my parent’s house, when we sit down to eat, we can’t say no to any food— “Someone has put in their time and energy into making this,” my mother has always said. We also can’t dare to waste food. While honouring another person’s time and energy into feeding us is — or should be — a universal concern, my family’s reasons for respecting what’s on the plate run deeper still. My parents were born into a people who had lived the trauma of three partitions and a famine, and have seen people drop like flies out of hunger. Food for them, and through them, for me, was never a right but always a privilege. I have grown up being told that I am a descendant of people who saw the worst that hunger can do, and survived. So no, I can’t, won’t and shouldn't ever waste food.

There’s a scene early on in Darkest Hour where Winston Churchill (played exceptionally well by Gary Oldman) eats his breakfast — scrambled eggs, rashers of bacon, a glass of champagne and a shot of Scotch — laid out on a silver tray among crystal salt and pepper shakers and shining cutlery. It’s 1940 and he’s going to become the British Prime Minister. In his impatience to dictate a letter, he puts away his lavish breakfast and puffs on his cigar, probably never touching that food again. This is the man who, in three years, would go on to engineer the Bengal Famine that killed three million people.

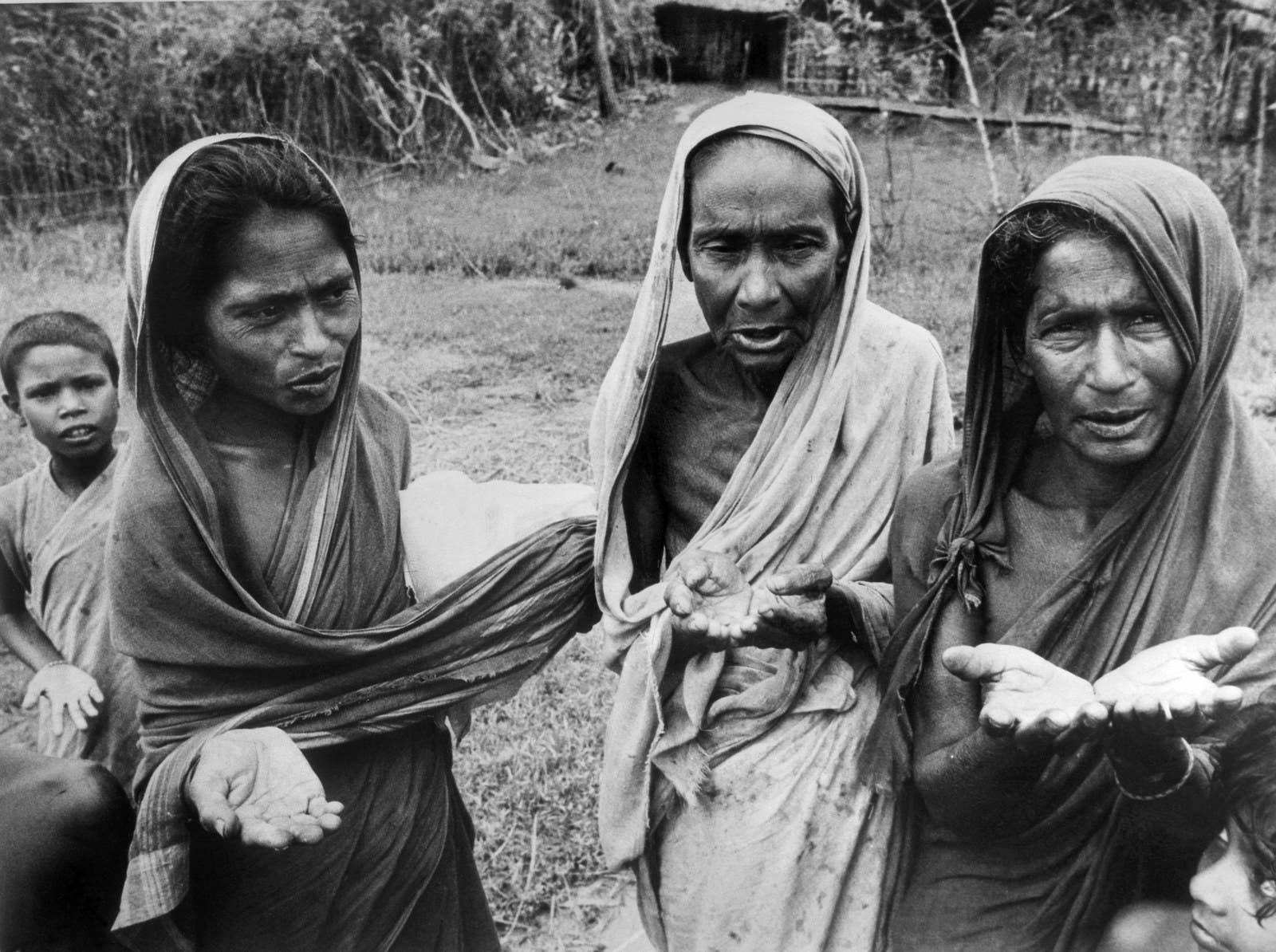

For my family, and millions of other families around Bengal, our relationship with food dates back to the Bengal Famine. 75 years later, I am still grateful for the rice grain that makes its way to my plate. For years, the people of Bengal would grow rice that would be siphoned off in its entirety to feed British troops and citizens. The food debt would grow so large that it would create one of the biggest famines in world history. The trajectory of hunger follows a very clear trajectory of hierarchy; we lost our millions to starvation and there’s a static silence over this in our books, while we never stop hearing of the hardships and the difficulties of having lived in Europe in times of bread lines and rationed potatoes.

My generation has seen nothing like it and we probably lack the vocabulary or register to measure the trauma of living through a famine of such proportions. But we’ve all heard stories that have survived the generations. A friend’s grandmother once recalled to him how a starving man came to her door asking for some rice. She rushed to her kitchen to get some from her already heavily rationed stock and when she was walking back to her door, she saw the man had passed away. I never met her but I have grown up listening to my grandmother say that we must never refuse food to anyone who comes asking.

It starts with a kerosene shortage and then everything falls apart; civility vanishes, trusts are broken and promises ignored—all for a fistful of rice.

Churchill was posted in India in 1896 as the Second Lieutenant of the Fourth Hussars regiment of the British Army; a country he famously described as a “godless land of snobs and bores.” In 1943, he had most of the harvest land along the Bengal coast converted to air force bases to protect the colony against the Japanese. I remember watching Ashani Sanket and seeing how the fecund yellow and green of the rural Bengal rice fields slowly disappeared through the film. It starts with a kerosene shortage and then everything falls apart; civility vanishes, trusts are broken and promises ignored — all for a fistful of rice.

My childhood was littered with stories that came down from my grandparents — of the poor who went around the then-ghastly Calcutta streets begging to eat the starch that housewives threw away once their rice was cooked. They lay dying in thousands on the city pavements, as Churchill forced Australian ships carrying food grains to bypass Bengal. My grand uncle and grand aunt, were making their way back from Burma to their native town of Noakhali (now in Bangladesh) mostly on foot, walking through these sites battling thirst and starvation. When they finally reached home, my grand uncle succumbed to the exhaustion and trauma. Another friend grew up eating till the last grain of rice from her plate was gone; her grandmother had survived the famine but could never shake away the fear of waking up the next day and finding no food to eat. She was 17 when the famine struck its peak and 70 when my friend was growing up.

News of the death toll reached Churchill who said the famine was the price Indians had to pay for “breeding like rabbits.”

The British-founded clubs in Calcutta flourished and newer restaurants cropped up in the city centre of Chowringhee, while rural women took to prostituting themselves, parents sold their daughters and surviving family members were left with no money or strength to complete the last rites of the dead. My aunt tells me stories of mothers prostituting themselves to feed her children and then of the father who killed his children, unable to stomach the guilt of not being able to feed his children. While piles of dead bodies were being eaten by foxes and dogs, news of the death toll reached Churchill who said the famine was the price Indians had to pay for “breeding like rabbits.”

His reply was, “Why isn’t Gandhi dead yet?”

This when he himself was eating off India and presiding over armies full of Indian soldiers. This when Churchill was fighting Hitler, championing anti-Hitlerian virtues, while himself engineering a famine and celebrating it because it was “merrily” culling India’s population. This man was our Hitler and yet, where is the hatred? Instead, there are six Oscar nominations.

Last year, we had Dunkirk (eight Oscar nominations) — complete with a whitewashed all-White army of the Allied Forces. Similarly, the writer of Darkest Hour takes the liberty to write out a whole scene, completely and conveniently fictional, where Churchill takes a ride in the London tube, speaks to the passengers who stand in awe of him, asks them of their opinion on the war, listens to them reject the idea of peace talks and goes on to recite lines from Lays of Ancient Rome, which are then completed by a black man who he later high-fives. If Wright set the film a few years later, he’d probably have Churchill cooking in a soup kitchen for Bengal’s benefit.

To humanise his war mongering, is not just distorting history but also lying about it with a straight face.

Churchill was a famous racist. In the Darwinian power pyramid in his head, White Protestants occupied the top spot with Jews and Indians at the very bottom, right above Africans. This is something that has been written about by many historians and intellectuals, and most recently, Shashi Tharoor. Of course I have a problem with the film heroising this man and keeping quiet over the famine, but my larger rage is about what the film chooses to fictionalise. To show this man high-fiving a black man and bonding over Macaulay, just to humanise his war mongering, is not just distorting history but also lying about it with a straight face. I sat in a theater in New York City, thousand miles away from Bengal, watching this and doubting everything I know about my history and this man’s role in it. A feeling very close to being gaslit. All my grandmother’s memories, all the stories we grew up hearing, our childhoods and the gratefulness with which we accept food, were all falsified.

As a film and literature student, I understand the genre of historic fiction and the limits of that fiction. We have spent decades reading post-colonial theory, trying to dig up narratives from the silent borders of history, and not for it to come to this day where we sit in a theater and have yet another white man tell us, 70 years after they left our country after sucking it dry, that they were nothing but good to us? That they have nothing but heroes among them?

One realises the practical need to heroise fascists like Churchill and to construct a narrative of a glorious past for Britain, especially in these post-Brexit times. A country found on shameful violence needs a history to celebrate, when they really haven’t done much that needs celebration. So it lies. However, it is one thing to try and humanise a war-mongerer and murderer, and make a national hero out of him during a time of acute national identity crisis and quite another to, rather immorally, construct a lie so big that it glosses over the truth of the painful history a colony suffered for two centuries. In its bid to lie to itself, Britain is creating a narrative that makes light of the history of a billion people.

Of course, it’s nothing they haven’t done before.