An international stem cell research team announced the creation of the first human–pig embryos on Thursday, opening a new frontier in research into “chimera” mashups of human and animal tissues.

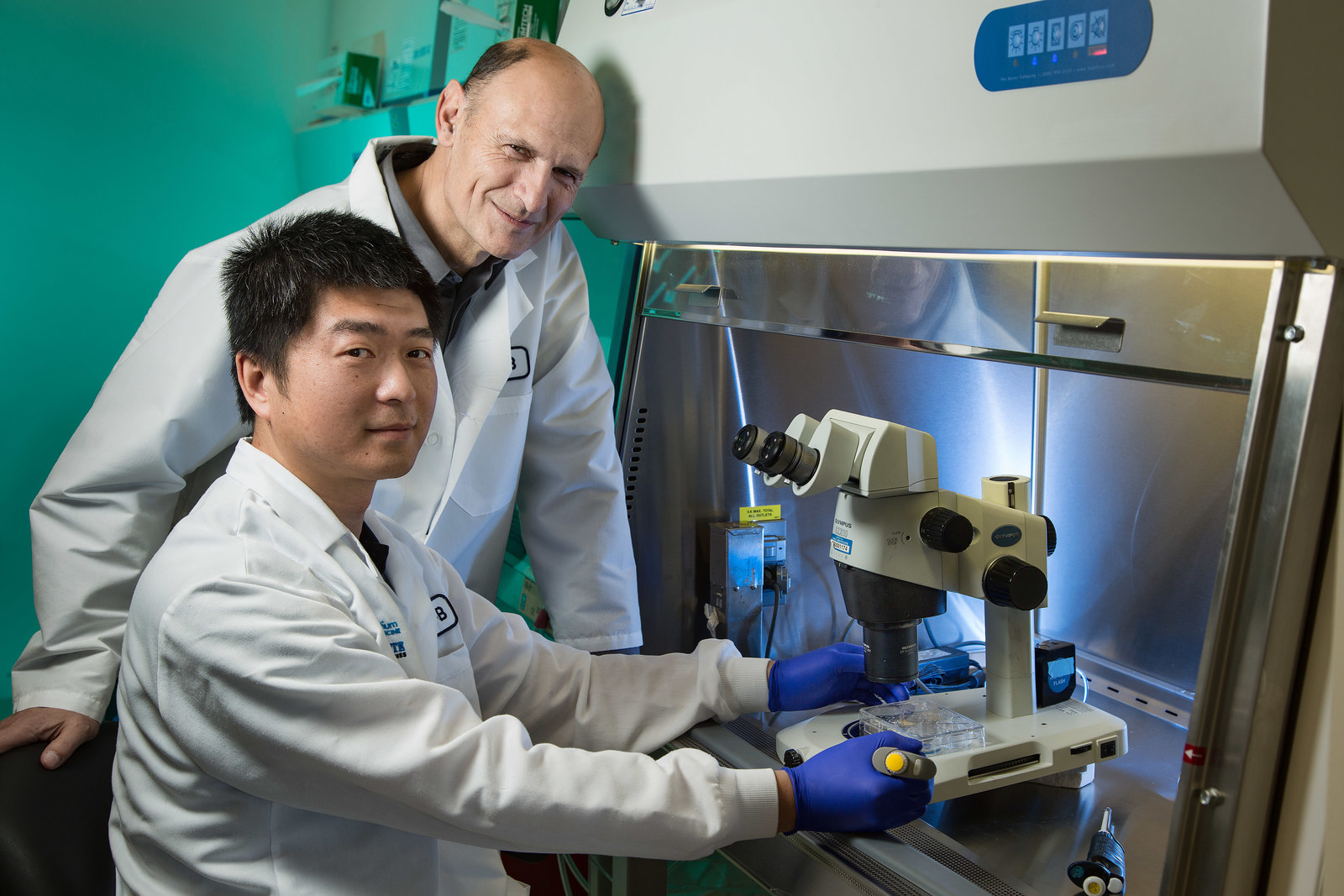

The study, conducted by a team at the Salk Institute in California in collaboration with researchers in Spain, is one of several early attempts to grow human tissue inside animals to produce organs needed for transplants such as hearts and kidneys.

“It’s important because we have been able to respond to a question that the field was asking: Can human cells be mixed with a large animal? The answer is yes,” team leader Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte of the Salk Institute in San Diego, told BuzzFeed News.

While labs have previously created human–animal chimeras, such as mice transplanted with human cancer cells or immune systems or even brain cells, these new experiments, published in the journal Cell, are unique because they place human stem cells — which can grow to become any of the different types of cells in the human body — into animal embryos at their earliest stages of life.

Implanted at these early stages, animals born from such chimeric embryos would possess a unique combination of human and animal cells.

But the studies, which make the lines between human and animal species murky, have already ignited anxieties around potentially “humanizing” animals, as well as stoking broader fears about tinkering with nature to create life seen as unnatural.

In 2006, then-President George W. Bush called for making human–animal chimera research — which he called "the most egregious abuses of medical research" — punishable by a $1 million fine and up to 10 years in prison. The bill never passed, but in 2015, the National Institutes of Health placed a ban on federal funding of any chimera research using human stem cells, saying that the possibility the animals could end up with human-like brains — and potentially, human-like thoughts — was a strong enough reason to exercise extreme caution.

Instead, Belmonte’s team were funded by private donors in the US and Spain. They argue that their work is necessary, and that any fears surrounding the products of their research, while entirely understandable, are unwarranted. To address this, the team killed the embryos early on, by four weeks of their development.

“People worry about the germline and the brain — creating a sentient animal,” Jun Wu, who led the study with Belmonte, told BuzzFeed News. “But if we don’t allow the animal to be born, then it’s just a mixture of human cells with the pig cells at the early developmental stages. To us, that shouldn’t raise any ethical concerns.”

“Not everything that we scientists can do should be done,” Belmonte added.

Some bioethicists agreed. With 22 people a day in the US dying while on waitlists for organs, Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve Medical School, told BuzzFeed News, researching human–animal chimeras — however uncomfortable it makes some — is crucial.

“The basic impetus behind this research is the sort of holy grail of regenerative medicine— to help us replace our body parts when they’re sick or diseased,” Amy Hinterberger, a sociologist at the University of Warwick who specializes in human–animal chimera research, told BuzzFeed News.

But, Hinterberger pointed out, mixtures of species have always inspired fear in humans. Chimeras in Greek mythology were monstrous lions with goat heads and snake tails. “To some extent the figure of the chimera has always played an important role in our cultural imaginaries about what’s natural, and what’s not,” she said. “It’s something we still don’t know how to grapple with.”

“Most of the labs around the world are trying to obtain [organs] by growing cells in a petri dish,” Belmonte said.

Belmonte described how this type of research, pursued for more than 10 years, has run into trouble since scientists aren’t yet sure what makes stem cells differentiate into things like organs or muscle cells or brain cells in the first place. What’s more, growing cells on a flat plate makes it hard for them to assemble into the three-dimensional structures of organs.

“So, we said, why don’t we let nature do the work for us?” Belmonte said. “Why don’t we put human cells inside embryos? They know very well what to do. We wanted to try to have human stem cells not guided by us scientists, but by the embryonic environment.”

Despite success creating rat–mouse chimeras (one lived two years, setting a longevity record), doing the same experiment in pigs using human stem cells was significantly harder for the team. One reason was that pigs and humans are separated by 95 million years of evolution. Another was that human embryos have a much longer gestation time than pigs, which are born after just 114 days. Getting human stem cells to incorporate into the pig embryo required tricky timing, which Belmonte likened to merging onto freeway lanes moving at very different speeds without crashing into oncoming traffic.

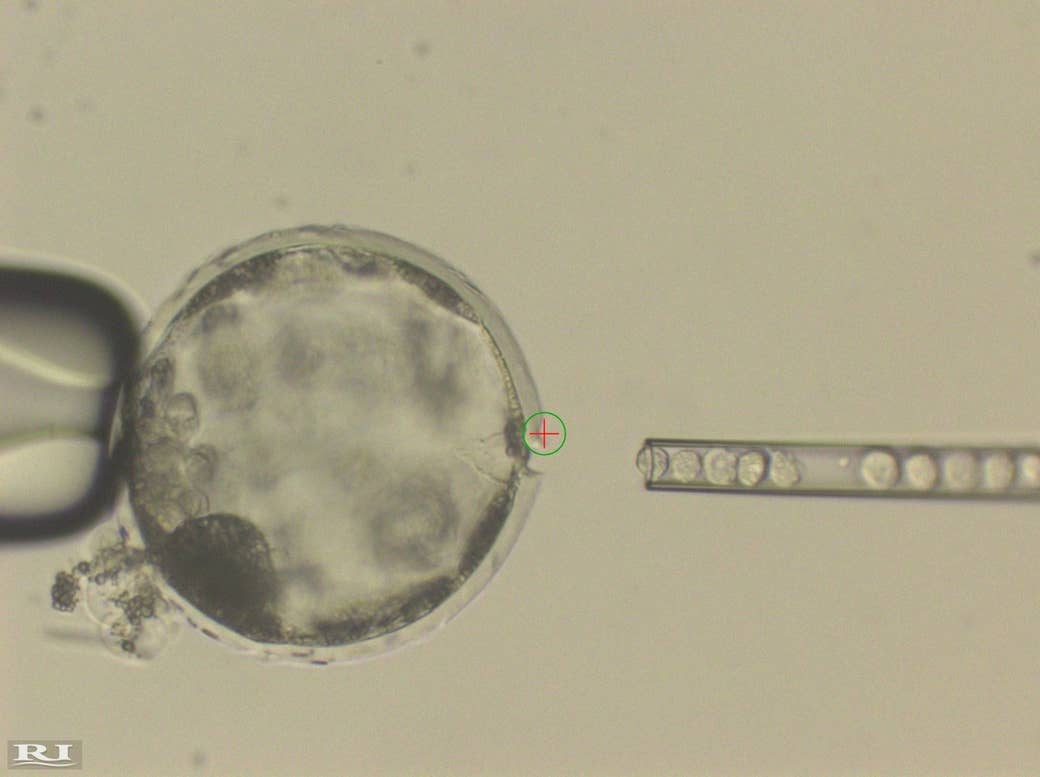

Once they successfully injected the pig embryos with the human stem cells, the team implanted 41 female pigs with 30–50 chimeric embryos each. Only 18 pigs successfully got pregnant. The scientists then extracted the embryos at 3 to 4 weeks old, or one-third of the way through the pig’s pregnancy, to address concerns that any of the human cells would have found their way into the developing pig embryo’s brain. Without having an animal actually born, but still having all of the organs of the embryo available for study, the scientists avoided their main ethical hurdle — bringing what might be considered a human-like pig into the world.

What they found was that the human stem cells had incorporated into the pig embryo, mostly clustering in the muscle cells, some organ precursors, and the spinal cord. They detected no human cells in the brain. But the pig had very low levels of human cell contribution overall — roughly one human cell per 100,000 pig cells — an efficiency problem the team will need to address if they want to use the pigs to create human organs down the line.

“This is a small step, but it’s a very important proof of principle,” Hyun said. “People were really hoping for this.”

Belmonte and his group hope that in future experiments, they will turn off certain organs’ development in the pig, which would force the human cells to fill in the gaps to make fully human transplantable organs.

“The prospect of growing a human organ may still be far away, but there are other applications that are closer: modeling human disease, drug screening, studying evolution, and understanding early embryogenesis,” Belmonte said.

At the same time, they’re hoping to develop strategies to ensure the human cells don't make their way into the pig’s brain.

“Most people are concerned that if you mix too much human material into the brain of a large animal, it may start having conscious experiences that are more human-like. That’s so hypothetical, we’re not anywhere close to that yet,” said Hyun. “The bigger issue is the animal welfare question: What is the well-being of the animal that’s gestating, the animals that you use to get the embryos, and what’s the welfare of the thing you’re going to birth live.”

Nevertheless, the researchers hope the NIH might be changing its tune on funding chimera research. In November of 2015, 11 scientists published a letter criticizing the NIH for creating a "threat to progress" that was based largely on unfounded fears. Last August, the agency opened up to public comments on its policy regarding human-animal chimera research. Meanwhile, the thorny issues surrounding chimera research are still being weighed by the agency, and the ban is still in effect.

“People are concerned about humanization — in relation to the brain or reproductive capacities — but we’re not used to talking about being human in such definitive ways,” said Hinterberger. “For now at least, we don’t really have very good metrics for human-ness.”