The new poster child for extreme drug price hikes is a talking gadget that automatically injects a life-saving drug into overdose victims — at the steep cost of $4,100 per twin-pack.

Called Evzio, the device was approved in 2014 and is marketed as an “auto-injecting” talking naloxone dispenser for people who may feel worried about injecting the drug properly into a friend or family member in the panicked moments following an opioid overdose. While it started out costing $575, the drug’s manufacturer, Virginia-based Kaléo, hiked the price up to $4,100 last year.

The new cost of Evzio puts it at roughly 30 to 100 times more expensive than alternative naloxone injections. Even so, use of the device has now grown to more than 40% of naloxone units sold in the US — despite the price hike, and amid a nationwide epidemic of painkiller and heroin overdoses.

“There is about $2 worth of drug in this talking device,” Adriane Fugh-Berman, associate professor of pharmacology at Georgetown University, told BuzzFeed News. “But this is a drug without which many people would die.”

Kaléo has also developed an auto-injecting epinephrine device called AUVI-Q that’s priced at $4500, for treating allergic shock reactions. This is more than seven times the cost of the EpiPen, which caused an uproar when drugmaker Mylan hiked its price up from $250 to $600 last year.

While “pharma bro” Martin Shkreli has become the face of a broken drug pricing system in the US, and President Donald Trump raised the issue in a meeting with pharmaceutical companies on Tuesday, the timing of Evzio’s price hike last year was particularly chilling, doctors and advocates say. In 2015, more than 33,000 people died of opioid overdoses in the US, the highest number ever recorded.

“Naloxone is the only antidote for an opioid overdose that we’ve got,” said Ravi Gupta, a medical student at Yale who co-authored a study in December highlighting the drug pricing issues with naloxone. “It’s egregious that this is happening at all, but it’s way more egregious that this is happening while we’re in the middle of an opioid epidemic.”

Others argue that the high cost of the Evzio device is unjustified when the drug on its own, without the fancy packaging of a talking gadget, has already saved tens of thousands of lives.

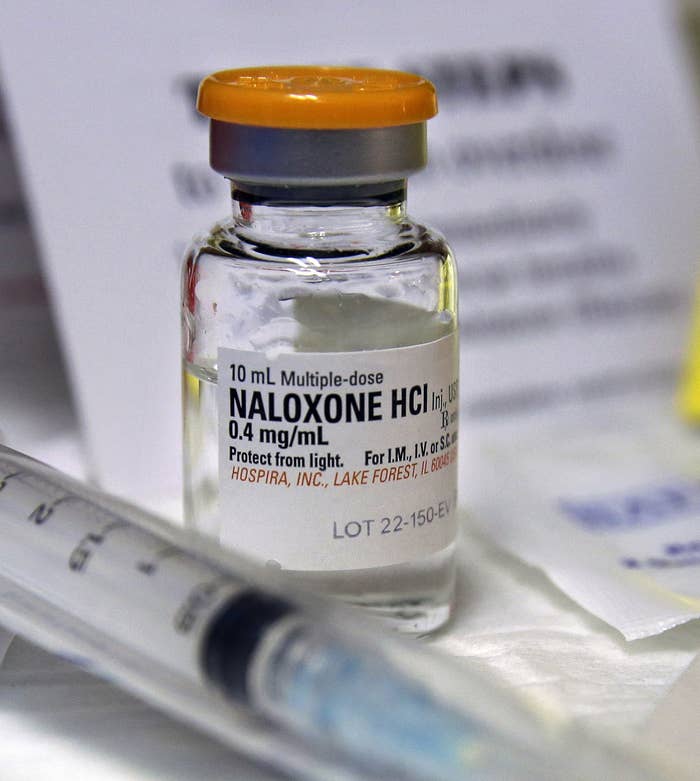

Naloxone was first approved for as an injectable antidote for opioid overdose in 1971. Generic versions of the drug have cropped up on the market since 1985, and today, there are four main formulations for the drug: two different doses of injectables, a nasal spray that came on the market last year, and Evzio.

Prices have gone up for naloxone across the board, with costs for the injectables doubling in recent years, and the nasal spray being priced well above that at $150. But Evzio, which markets itself as using “Intelligent Voice Guidance” technology to guide people through the auto-injection of the antidote, is priced at nearly 25 times higher.

Kaléo defended its price increase by arguing that it has allowed the company to subsidize the cost of the drug for those with high co-pays, or those without private insurance who make less than $100,000 a year.

“There’s quite a bit of misinformation out there right now about this pricing,” Spencer Williamson, Kaléo’s CEO, told BuzzFeed News. “For the vast majority of people in the US, the cost out of pocket is zero dollars.”

Williamson argued that in the time since the price hike has gone into effect, the number of people using Evzio has gone up 300%, evidence that more have been able to get access to the drug in the wake of their price hike.

But others argue that rebate programs, long touted by pharmaceutical companies as a cost-saving measure for consumers, actually end up costing everybody more in the end.

“The government is covering most of the drug costs in this country, so it’s really taxpayers that are paying for it,” Fugh-Berman said. The higher drug prices also end up leading to higher insurance premiums.

“High drug costs are borne by the consumer whether or not they’re actually paying a higher price at the pharmacy counter,” she said. “Kaléo is profiting off of this, and giving away their product is a way of deflecting criticism.”

The price hike has also come as state and federal agencies have tried to get naloxone into the hands of more people. Naloxone is traditionally used only by medical professionals, but the CDC has since recommended that doctors co-prescribe it to patients being prescribed opioids. Hundreds of police departments now require officers to carry naloxone, and nearly 40 states currently allow people without a prescription to get the drug at pharmacies through standing orders. According to Gupta, the number of states that have written laws trying to expand naloxone access has increased from eight in 2012 to 46 in 2016.

“It’s not something that is even on the table for us to be able to afford,” said Alyssa Aguilera, executive director of advocacy group VOCAL NY, whose group has trained thousands of people on how to administer naloxone injections and helped pass the law putting a standing order for the drug in 750 pharmacies across New York.

Aguilera noted that Kaléo had sent her group a sample Evzio device in the mail, but no one had tried it because the price made it a nonstarter next to the much cheaper injectables or spray. And New York’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene stated that Evzio is not included in the 14,000 naloxone kits it distributes per year.

“I think it’s particularly dangerous for communities that don’t have syringe exchanges or harm reduction organizations,” Aguilera said, "because that price will impact those consumers with a more heavy hand."